When Tori Amos’s 1996 album Boys for Pele was first released, she explained that after she broke up with her partner, Eric Rosse, she started “stealing fire” from the men in her life. The fire she described was a kind of energy, primarily in the form of admiration. When Amos recognized she was vampirically feeding on all these men, she pulled herself inward and began recollecting the pieces of herself she had excised or unconsciously given away. The result of this recollection process was Amos’s third studio album, Boys for Pele.

The World of Boys for Pele

On Boys for Pele, Amos served as sole producer for the first time in her career. The bulk of the album was recorded at a church in Delgany, Co Wicklow, Ireland (watch the EPK to see how they did it) and the rest was recorded in New Orleans. The finished album consists of 18 songs, and if you include the B-sides (and other tracks released later on), a total of 35 songs were written and recorded during this period, which is impressive by any standards.

In terms of production, Amos relied primarily on her voice and her Bösendorfer piano, but she also utilized the harpsichord, pump organ, and clavichord. Throughout the recording process, she was supported by George Porter Jr. on bass, Steve Caton on guitars, Manu Katché on drums, The Black Dyke Mills Band on brass, John Philip Shenale’s string arrangements, a small gospel choir, and an actual bull. The production on this album is very precise; the arrangements are often sparse, yet colorful and imaginative. The overall tone is warm and intimate. You feel close to Amos as you listen—not just emotionally but physically, too, as if you’re sitting next to her on the piano bench.

In terms of the recording process, it’s also worth noting that two tracks, “Marianne,” and “Not the Red Baron,” were never demoed, and were written as recorded (this is also true of some of the Boys for Pele B-sides, as well as the song “Bells for Her” from Under the Pink). The slight difference in the recording quality on the improvised songs is noticeable on “Marianne,” because Amos’s voice is slightly quieter compared to the other tracks, as if she’s further away from the microphone. This is probably because the sound engineers weren’t expecting her to improvise a fully formed song in a single take. I think, both then and now, that this is almost unheard of, especially in the world of rock or pop music (or however you would categorize Amos’s music. I never really know how to do it, especially for this album).

Lyrically, Boys for Pele is probably Amos’s most expansive album, in terms of personal, cultural, historical, and mythological references. There are figures from Amos’s life, like her childhood friend, Marianne, her father, and of course, her former partner, Eric Rosse, but there are also World War I pilots, Anne Boleyn, Angie Dickinson, Muhammad, Inanna, Pele, and the unnamed-but-definitely-female Christ figure. In the B-sides from this era, there are references to Amos’s maternal grandfather, the Endless, samurai, Japanese motormaids,and a friendly, deceased childhood neighbor named Mr. Jim. Amid these references are cutting, incisive lyrics like, “I shaved every place that you’ve been, boy,” and statements meant (I imagine) to shock, such as “Give me peace, love, and a hard c*ck.” But there are also the free associative lyrics of “Horses” and “Marianne” that spiral out from themselves, as if self-generative (the fancy term for this is parthenogenic). So, even though Boys for Pele is technically a solo album, Amos was not alone in any sense.

In 2016, Boys for Pele was remastered and re-released as a two-disc set. The second disc consists of B-sides, demos, and live performances, and includes previously unreleased material, like “To the Fair Motormaids of Japan.” I’m not always a fan of remasters, but this one is worth the money. The sound quality is stunning, and the clarity is indescribable, especially if you have a good pair of headphones. Each piano note is like a glimmer of polished marble; the clicks and plucks of the harpsichord are so close to you, it’s mind-blowing. You can hear every note. The same is true of Amos’s voice, which shimmers and shines as it reverberates through the church.

So, what is Boys for Pele?

Boys for Pele is often described as a breakup album, and sure, there are few songs that reference breaking up with someone, like “Doughnut Song,” and “Putting the Damage On,” (or even the rage of “Blood Roses”) but I don’t think of it that way, because most of the songs aren’t about Amos’s breakup. But I also don’t know how to thematically define or categorize this album, beyond describing what it feels like: listening to Boys for Pele is like listening to someone get (intensely) reacquainted with themselves through sound; the musical protagonist is utterly present in every moment, so as a listener, you’re always leaning over an edge, unable to anticipate what is coming. This album has an intuitive, inner logic, and its seemingly fragmentary content is nevertheless contained within a coherent structure; the songs make a strange kind of sense together. It’s a personal, introspective, and vulnerable record, but it’s so rich in myth and metaphor that it never becomes solipsistic, clichéd, or repetitive.

Boys for Pele is also an album of emotional extremes. There are moments of despair, yearning, rage, and playfulness. Somehow, the gentle finale, “Twinkle,” exists in the same universe as the spidery harpsichord chaos of “Professional Widow.” But these extremes must coexist precisely because their separation and exclusion initiated the process of recollection in the first place. At bottom, Boys for Pele is the story of someone looking for the lost pieces of a self that was dismembered, scattered, and slowly reclaimed piece by piece.

This album may be too enigmatic, esoteric, or even too raw for some listeners, but for the rest of us, well, we’re still hooked. I first heard this album when I was 14, and here I am, 18 years later, still fascinated by it and still listening to it.

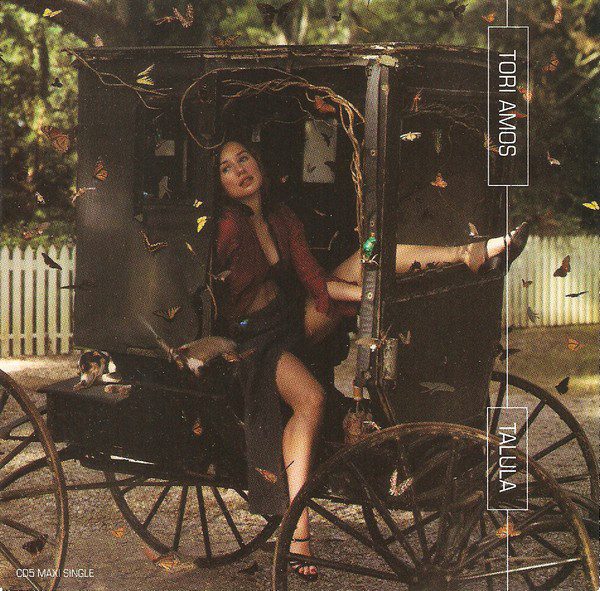

The Album Art: Sacred Profanity

The album art of Boys for Pele is both striking and provocative. On the album cover, Amos sits in a rocking chair holding a rifle; a dead cock (her words) hangs to her right; and a thick snake is wound around the leg of the chair. Amos has one leg hanging out of her pants and stares forward, looking into the viewer. It is an expression of power and liberation, and a reclamation of her southern roots. It’s also a nod to a deeply confessional song from Little Earthquakes, “Me and a Gun.” In perhaps the most infamous photo of this era, Amos holds a baby pig to her breast, as if breastfeeding it. These images are metaphorical, eye-catching, and intense. Several other photographs, which were less extreme, were released with the album’s various singles and EPs. One of my favorite images is on the “Hey Jupiter EP.” In it, Amos rests on a tree branch and looks longingly into the distance as a brilliant field of stars shines behind her.

In another photo series, featured on the various versions of the “Caught a Lite Sneeze” single, Amos is on her hands and knees on a dirty mattress in muddy farmland; there are bulls in the background, pieces of glass hanging from trees, and as far as I can tell, she is only wearing one shoe. In another photo from this series, she lays on the mattress near a bonfire; it is night, and she is surrounded by lamps, spindly branches, images of Jesus and Mary, some sort of skeleton, and various detritus. To me, this image depicts the process of the album’s creation: a spontaneous ritual incorporating the dirt and mud of the earth and the fire of the spirit, which ultimately resulted in Amos finding a refuge within herself.

Pele on Tour: “Do Drop in at the Dew Drop Inn”

The tour following the album’s release consisted of roughly 187 shows; sometimes Amos played two full sets in a single night. On stage, Tori was joined by Steve Caton on guitar, as well as her Bösendorfer piano, harpsichord, and pump organ. The performances were frenzied, improvisational, poignant, and of course, fiery. Amos truly brought Pele’s energy along for the ride. As usual, Tori often organized her set lists around fan stories and requests; she frequently improvised and covered many songs, ranging from straightforward (but stunning) Elton John covers to strange, powerful medleys.

I wasn’t there, but I have listened to and watched so many hours of this tour that I feel like I was. The intensity of these shows is so palpable, and sometimes the energy from the audience feels almost out of control—people scream at the top of their lungs at a woman sitting at a piano. I even remember one show in which Tori had to kindly request that the audience calm down a little, because they were so loud she couldn’t hear herself. And every show was unique: sometimes there are a dozen versions of a single song, each with their own vocal, musical, and even lyrical improvisations.

Sometimes, new live versions of songs emerged and continued to evolve, even beyond this tour; sometimes new intros and improvisations passed through, waved hello, and moved on. But the consistent variable was Amos’s courageous receptivity. She remained authentic to her instincts, and she was always open to the energy of the room, whether it came from the audience, the theater itself, or a ghostly presence hovering around the piano. Amos was alive and open to all dimensions and possibilities, and she adeptly navigated each performance based on the flood of information she received.

But the discovery of fire comes with a cost. There were performances, radio interviews, and TV appearances during this period where, to me, Amos seemed distinctly unwell. Amos has a preternatural ability to give, especially to her fans, and sometimes I wonder if she gives too much of herself. A particularly somber part of this period was the unofficial “final” show of this era (technically the tour ended in November, 1996, but Tori performed live on two other occasions before beginning to work on her next album). This show is legendary, but is tinged with loss.

On January 23, 1997, Amos performed at Madison Square Garden to help RAINN, a nonprofit anti-sexual assault organization. The organization, which Tori had been involved with since its inception, was in financial trouble, so the show functioned as a fundraiser. But the performance came within weeks of Amos having a serious miscarriage. Excluding the duet, I can’t watch most of this performance. I feel like she called upon every resource imaginable to make the concert a memorable success but did so at the expense of her own well-being. Again, Amos is always willing to give, and sometimes gives too much. But the tragedy of the miscarriage led Amos to rediscover not just fire, but life force itself, which was the focal point of her next album, from the choirgirl hotel.

The Legacy of Boys for Pele

Boys for Pele and the “Dew Drop Inn Tour” live on as some of Amos’s most beloved work, but I’ve observed that some of her fans wish she still wrote and performed in the same manner, as if she shouldn’t change, experiment, or grow. I love this album and I am so grateful to be able to watch (and rewatch and rewatch) performances from the tour, but I’m glad she moved on. I’m glad she started a family, built her own studio, recorded many albums with a full band, and ventured into numerous musical directions. I’m also relieved she stopped pushing herself to extremes to please her audiences. Once Amos reclaimed her fire, she didn’t need to keep looking for it anymore.

A creative journey like Boys for Pele shouldn’t be repeated, nor should it last forever. But we are lucky—we can revisit this album as much as we please. This album is, by my estimate, an experimental work of genius: it is eccentric, free associative, gorgeous, and mad. It begins in the twilight silence of a girl standing in front of a bathroom mirror, followed by the thundering rumble of horses, which signal our descent; we have tea with Lucifer, meet the Black Widow, dance with Talula, hang out with Muhammad, sing to Jupiter, and shed a year for the fallen WWI pilots; we descend into the mythic American south, enveloped in its fragrant humidity and suffocated by its racism; we feel the burning pain of loss, broken promises, and the hazy presence of a ghost passing through our skin.

The story ends not in a volcano, not even in a bonfire, but in a gentle, twinkling candle; a single light flickering steadily in the dark, burning, glowing, alone but at home in itself, at peace.

Boys for Pele has battled it out for my favourite album ever with Joni Mitchell’s Blue. I agree with what you said about the remasters being worth it. A bottle or two of a nice red wine and some great quality warmed-up headphones and I can still find new facets on this diamond of an album.

Agreed, on all fronts! Thanks for reading.

Boys for Pele has battled it out for my favourite album ever with Joni Mitchell’s Blue. I agree with what you said about the remasters being worth it. A bottle or two of a nice red wine and some great quality warmed-up headphones and I can still find new facets on this diamond of an album.

Agreed, on all fronts! Thanks for reading.

She’s always said that if she delivered Under the Pink Part 2, she’d have no career. This album was most definitely her declaration of who she is as an artist. Are you excited about Ocean to Ocean?

Oh god, UTP part 2, could you imagine? I’m glad she always reinvents herself. And yes, I am very excited for Ocean to Ocean! I plan to write a review for it, which will be a challenge in and of itself – I’ve had years to consider Boys for Pele (and the other songs I’ve written about) so this will be a new experience. But yes, I’m excited. Thanks for reading!

She’s always said that if she delivered Under the Pink Part 2, she’d have no career. This album was most definitely her declaration of who she is as an artist. Are you excited about Ocean to Ocean?

I love that she now describes this album as her “punk” album. When I discovered Tori I was deep into classic punk…

Within the context of what punk wanted to represent and outside of the “punk sound”, I always felt the subversion of what the record company wanted from her.

She produced this art on her own for the first time.

Outside of the societal context of punk, Pele is so many things, but absolutely truly punk at it’s core and base concept.

The “organ” she recorded and toured with is a Wurlitzer amplifier. The outputting speaker spins as she plays.

The “Wurli”, as Tori calls it, couldn’t fit in the church.

When it kicks in on “Horses” (…”off with superfly”…)

She had to record that bit in the churches graveyard!

While songs were planned and layered on this album, she did a great deal of recording them in one take.

Between separating with her ex and long time producer, Eric Rosse, she had a couple notable a-list flings that she brought to Pele. Primarily Trent Reznor, who she stayed with during some of the New Orleans portions of recording.

At the time he was living there in the house Sharon Tate grew up in. He was nicknamed by locals at the time as “the bell of New Orleans”.

Also “Made my own Pretty Hate Machine”

Is such a clear nod to that romance that didn’t work out.

(It’s rumoured Trent cheated on Tori with Courtney Love… Tori wrote “Professional Widow” with nods to Courtney.

And I thoroughly believe “She’s Your Cocaine” is another nod to Trent.

Trent wrote “Starf*ckers Inc.”

In response to Courtney messing something good up, but also a nod to “Professional Widow “.