Official Gala Presentation of the 57th Chicago International Film Festival

When Kenneth Branagh’s Belfast turns back its clock to 1969 and tints itself into the monochrome palette of black and white, a large sign appears mounted on the end of a row of houses that acts a de facto welcome mat to the bustling little street in the Tiger Bay neighborhood our movie inhabits. Painted on it is a well-worn saying that quotes a portion of 1 Timothy 1:15 and states:

“This is a faithful saying, and worthy of all acceptation, that Christ Jesus came into the world to save sinners.”

Curiously, the sign leaves off the last five words of the Bible verse: “of whom I am chief.” If you didn’t know that, the verse, as it’s presented, would sound like a thorough recruiting statement for the religious spine of this blue-collar corner of Belfast. However, once you add the final portion, it can read like it’s missing a stance of personal admission. With the professing of sin comes penance and restored relationships. Enter Kenneth Branagh, who spent the first nine years of his life in the city before moving away at the beginning of The Troubles in 1970.

In so many personal ways expressed through his chosen visual art form, Belfast feels more than an affectionate salute from the displaced Belfast native and five-time Oscar nominee. Reflecting on half-century-old memories for the man behind the camera and scripted page, Belfast may indeed desire to be each of those aforementioned healing measures and then some for Kenneth Branagh. His extraordinary and tenderhearted film stands, runs, dances, sings, cries, and dreams its way to a crowning peak as one of the best films of 2021.

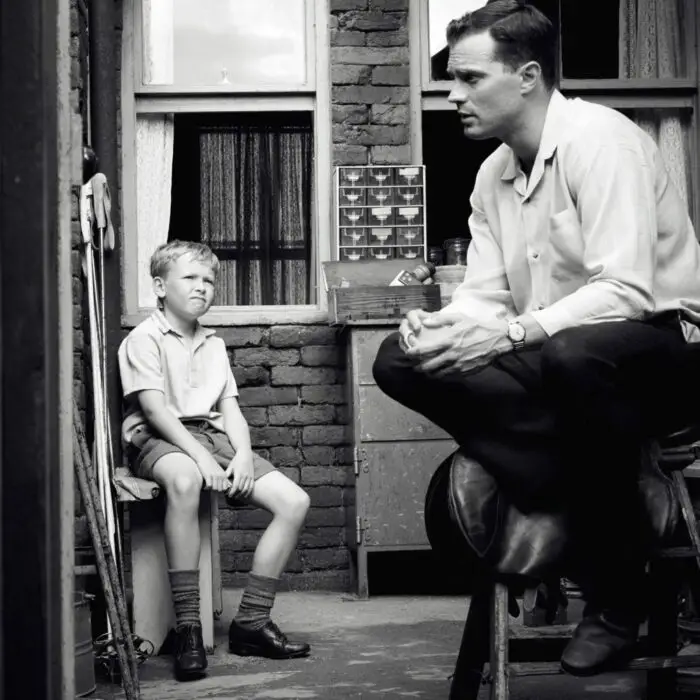

Once the color changes and the high cameras descend into the citizens of this era, our chosen point-of-view in Belfast becomes local rabble-rouser Buddy, played by newcomer Jude Hill. He adores family, soccer, a girl in his class at Grove Park Primary School, and movies – not necessarily in that order. Buddy’s community wraps his charmed life in those very things. The household is run by his mother (Outlander’s Caitriona Balfe) while his gambling father (Fifty Shades of Grey’s Jamie Dornan) works for weeks at a time out of town to pay down debts. Buddy’s pert grandparents, played with sweet sagacity by Judi Dench and Ciaran Hinds, are nearby help and loving influences.

On the morning of August 15th, things turn from happy to harrowing in a hurry. What began as a normal, peaceful day turned ugly when Protestant rioters filled the streets to vandalize and attack Catholic homes. Locked into the head-spinning and camera-circling child’s gaze of jarring events, Buddy and everyone else took cover and weathered the first storm. Overnight, the commoner hamlet was drastically upended and scarred. While neighbors helped neighbors clean up and rebuild, the very concrete in the streets was razed to create “peace wall” security checkpoints with constant police and army presence, scanning helicopter spotlights, and torch-bearing community watchmen at night.

To Buddy, the barbed wire, rubble, and extra people and noises are just new obstacles to move around while reading comic books or playing soccer. The gravity only hits slightly as the boy invents logic for adult situations. Combine his first-hand observations of these changes with the sensory digestion of the ever-present TV and radio reports, and a child’s psyche will create their own interpretations of what’s transpiring. The range between fearful honesty and fantastical gossip all applies for Buddy. His parents and grandparents soften or shield every grim truth they can with chin-up deflections.

Branagh’s trusted cinematographer Haris Zambarloukos (their seventh collaboration with an eighth on the way with Death on the Nile next year) strongly aids this children’s perspective to the picture. He sets many of his shots to peer through doors, windows, and confining hallways in true voyeuristic fashion, matching a kid watching with interest at a distance. Those structures frame a solid sense of a lived-in home with meaningful foundations more than mere imaginary set creations. The effect is simple, subtle, and brilliant.

Echoing the notion of a child’s logic, religion and politics are learned behaviors and practices. Buddy and his family may be Protestant, but they have Catholic friends, including that flaxen-haired classmate he’s smitten with. With the words “not our side, not their side,” they are not rooted in any indoctrination and have not chosen a hard-lining faction. Righteousness and hate do not live in that home. That same neutrality filters down to Buddy, who sees everyone as neighbors to support and not other loaded labels.

When you have that genuine fairness instilled into a kid, the pillars of right, wrong, kindness, and respect become easier to demonstrate and enforce. The verbiage in the movie of “Be good and if you can’t be good, be careful” is a repetitive family saying that makes it frank and personal. My, if it were only that simple all the time! Bravo to these parents again, especially when faced with an escape route decision of leaving for the prospect of better jobs in England or safer shores as far away as Australia or Vancouver.

In those parental roles, the four primary adult actors are astonishing. Weighted by her character’s anchor to the only home she’s ever known and the protective duties as the primary parent, Caitriona Balfe exudes motherly muscles of dramatic strength. She commands a blistering scene in particular when she drags two kids by their sleeves through the rioters to return things they wrongfully looted while all hell is breaking loose, solely to prove a point of dignity. When Jamie Dornan is present, he represents a welcome dash of bohemian dazzle with his love for music and movies and an oasis of masculinity to stand his ground on behalf of his family. When Balfe and Dornan are together, their spousal debates and stretches for unity, also seen through Buddy’s lens, show the true conflicts of this time period were behind closed doors and pitted across domestic dinner tables.

The real scene-stealers though are Ciaran Hinds and Judi Dench. Hinds’ homely and cheeky mentorship of Buddy bathes this movie in adorable charisma. Dench matches him with feminine fluster asserting, like Balfe’s role, that women still run the show as necessary. When the two are away from Buddy, their senior wisdom shifts to put weary faces on the frightening reality that endangers the happiness they cultivated.

All of these lessons centered on Buddy’s experiences speak to the greater hopeful streak of generational bonds at the heart of the film. Backed by a soundtrack of nostalgic Van Morrison songs, the exit emotions of Belfast strike terrific chords for the power of home beyond brick and mortar. Branagh’s movie closes with a three-pronged tribute of “For the ones who stayed,” “For the ones who left,” and “For all the ones who were lost” as it transitions back to a current Northern Ireland where the healing has regenerated a viable city and region. Home follows you and can return to one all the same.

The filmmaker himself is a product of this final lesson and the poignant history that forced it to come to pass as it did. Even before this film, Kenneth Branagh was a native son absolved of the old struggles by succeeding in honor of his home. Stephen Colbert might have said it best when Branagh was recently a guest on CBS’s The Last Show when he remarked “The movie is so funny and so sad at the same time. I don’t think I’ve ever seen anything so Irish in my life.” He’s dead right. The movie warms you with mirth and destroys you with punch, just as a proper Irish creation should.