Earlier this year, I watched the 1968 Peter Bogdanovich film Targets on a whim. I had never seen any of Bogdanovich’s films, and I still really don’t know why I pressed “Play,” but I imagine it was because I saw Boris Karloff’s name. However, oddly enough, I had never seen any of Karloff’s films either, I only knew he played the mummy in the 1932 film, The Mummy (which inspired the 1999 film of the same name). I assumed that if Karloff had been a prominent actor during that era of American cinema, he would still be a skilled actor a few decades later, which proved to be true.

The first time I watched Targets, I was not aware any mass shootings had taken place in the United States in the 1960s. I was born in the late 1980s, and the first mass shooting I witnessed was the Columbine shooting in April 1999. In the years following Columbine, I watched in sadness and horror as the number of massive public shootings rapidly increased. When I first watched this film, I was shocked by its relevance to contemporary America.

The Story

Bogdanovich’s Targets tells two parallel stories that eventually intersect at the film’s climax. The first story follows the prominent actor Byron Orlok, adeptly played by Boris Karloff in his final serious dramatic role (however, several films were released after Karloff’s death in 1969). Orlok is, in many ways, simply a dramatized version of Karloff himself. He is an actor from the early days of cinema, and he constantly refers to himself as an old, outdated relic. The film begins with Byron’s abrupt decision to retire from acting. He cancels an upcoming film project with Sammy Michaels (Peter Bogdanovich) and backs out of a speaking engagement scheduled to take place the following evening after a screening of his most recent film, The Terror.

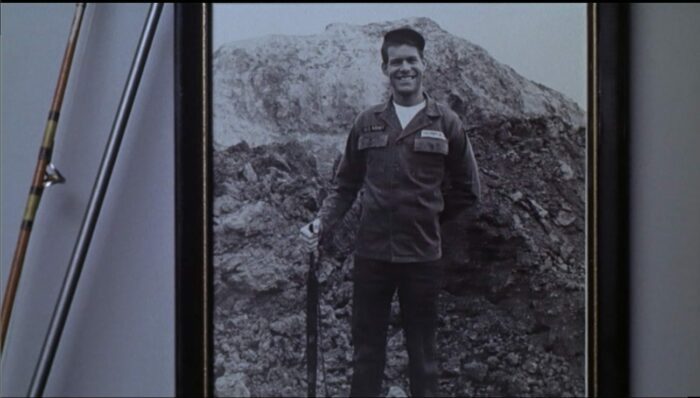

After Orlok’s story is established, the narrative suddenly shifts to Bobby Thompson (Tim O’Kelly) via the lens of a rifle scope. Bobby is a Vietnam war veteran, which is hinted at in a photograph in his bedroom. He is young, energetic, and by the standards of white 1950s America, an all-American boy. Bobby is a dutiful son who lives with his lovely wife and his parents. He refers to his father as “Sir,” and always has a quick, smart answer to every question. But it’s all a façade. Bobby is plagued by violent thoughts and his car trunk is filled with pistols, rifles, and heaps of ammunition.

During a brief outing, Bobby almost shoots his father. Then, after staying up all night, Bobby waits for his father to leave for work, then shoots his mother, his wife, and a grocery delivery boy. Later, he ascends an oil storage tank with his weapons, ammunition, sandwich, and a bottle of soda. After eating his lunch, he begins shooting at car passengers on the freeway. Eventually, the police arrive, and Bobby flees. He manages to evade capture by hiding in his car at a drive-in theater.

As Bobby’s action-filled story plays out, Orlok’s story continues. After a series of interpersonal bungles and a night of heavy drinking, Orlok relents and agrees to speak to the audience after his film screening, which is scheduled to take place at the same drive-in theater Bobby has taken refuge in.

As Bobby waits in the theater parking lot, he notices a doorway leading behind the large projection screen. He grabs his guns and ascends a network of metal scaffolding. Night falls and the venue fills with cars. Somewhere in the second act of Orlok’s film, Bobby begins shooting at unsuspecting viewers from behind the projection screen. At this point, Orlok and his assistant Jenny (Nancy Hsueh) have already arrived and are watching the film in Orlok’s town car. Eventually, the audience realizes what is happening and begins to race toward the exits in their cars, resulting in pandemonium.

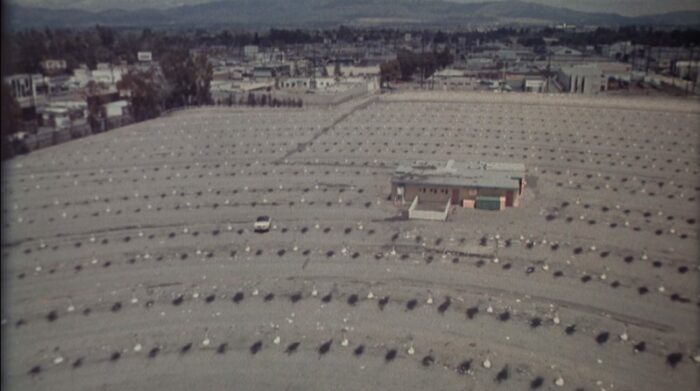

As the bodies are discovered, the theater staff finally calls the police. Bobby tries to flee and is eventually cornered behind a small wall. As Orlok, Jenny, and many others attempt to leave, Jenny is shot through the shoulder. Orlok, fed up with the senseless violence, approaches Bobby just as he runs out of bullets. Orlok knocks a pistol out of Bobby’s hands with his cane and slaps him in the face several times. Bobby curls up into a ball and sits in a corner, and the police finally apprehend him. In the last moments of the film, we see the flashing lights of police cars and headlights in the theater parking lot from above. Night becomes morning, and the theater lot is emptied of all cars and people, except for Bobby’s car, which sits alone in the vacant parking lot.

Bobby and Byron: Cold and Warm

The first time I saw this film, I was mostly absorbed by Bobby’s sociopathy and the way the film depicts his killings, particularly those that take place in his home. Although the shootings appear somewhat hokey and a little unbelievable, these moments are disturbing in the way we are forced to watch Bobby slowly drag bodies around his home. He drags his mother and wife into their respective beds and covers the bloodstains on the floor with small blue towels. There is no music, only Bobby’s labored breathing and the sound of his movements. The same dynamic occurs when Bobby ascends the oil storage tanks near the freeway. He drags heavy weapons over cement walls, crawls through chain-link fences, and climbs up large flights of stairs. Something about observing the extensive time and demanding physical effort required to commit these killings—and all the moments he could’ve stopped himself—makes these scenes particularly chilling.

One element that makes this film so interesting is the contrast between Bobby’s cold, sociopathic action-filled sequences and Orlok’s warm, funny, and thoughtful scenes. The character of Byron Orlok (and by extension Boris Karloff) represents older films and, for lack of a better word, more “traditional” approaches to storytelling. Orlok’s scenes are filled with monologues, dialogues, and witty (sometimes hammy) interpersonal exchanges; they feel like they were written for the stage. In one particularly memorable moment, Orlok tells Jenny, Sammy, and a few other characters an old horror story he wants to tell the audience after film screening is over. As he tells the story about a servant who meets Death in the marketplace, the characters observing him become his audience, become us; they are awed by his storytelling, just as we are, and Karloff shines. His delivery of this brief tale is stirring, and his performance makes it clear he is still a master of horror.

Another memorable moment of Karloff’s occurs during the film’s climax as he approaches Bobby. Karloff walks with such a commanding presence that it is impossible to pull your eyes from the screen—and he’s just walking. He also approaches Bobby from both sides: Orlok, in his final film, The Terror, is projected on the wall behind Bobby as Orlok in the flesh approaches him from the front. Bobby becomes disoriented and confused, which allows Orlock to strike him. This moment of confrontation between two characters is also the confrontation between two approaches to storytelling and film colliding on the screen.

In a sense, Bobby’s cruel and meaningless violence represents a new genre of horror and action-oriented films, which Orlok comments on in an earlier scene. In this scene, Orlok is sitting in his room with Sammy, and he says, “My kind of horror isn’t horror anymore.” He hands Sammy a newspaper and says, “Look at that.” The newspaper headline reads “Youth Kills Six in Supermarket.” Beneath the headline, a subheading reads “Honor Student Depressed,” most likely referring to the mental state of the murderous youth. Defeated, Orlok declares, “No one’s afraid of a painted monster.”

This moment feels both like a commentary on filmmaking and the senseless violence of the world. But in the final moments of the film, after Orlok disarms Bobby, he watches him cower in a corner like a scared child. Orlok says to himself, “Is that what I was afraid of?” Suddenly, he is liberated, not just from his film career, but from his fear of death and of feeling obsolete in a rapidly changing world. Having confronted his fears, he is free to live his life as he chooses; he is no longer caught in the dilemma of “Should I or shouldn’t I?” In a sense, the end of Targets is a kind of fantasy—the notion that the wisdom of age will prevail over the terrifying violence and impulsivity of (armed) youth. But even if it is only a fantasy, it is a fantasy that I enjoy.

Another important scene in this film comments on the role of violence and murder in storytelling from a slightly different perspective. In this scene, Orlok is watching one of his films on television (it’s an actual Boris Karloff film: The Criminal Code, released in 1931). At one point, Sammy enters the room, and they watch the final scene of the film together, which culminates in Karloff’s character brandishing a blade and backing someone into a room to murder them. But the murder is not depicted—it happens behind a closed door. It is implied, not shown. If I had to guess why this scene was included in Targets, I imagine it has something to do with the imagination. We can witness a scene like that and put the pieces together. We don’t need to be shown a bloody, gruesome ending; our mind will fill in what it does not see.

It is also intriguing to watch Orlok watching himself on a television while Sammy, the actual director of Targets, sits nearby. Different generations and perspectives on acting and filmmaking meet in this moment; it is a reflection about the history of cinema, how films have been made, how they’re being made, and how they could be made. Ultimately, it elicits more questions than answers.

Death From a Distance

The historical context of this film is significant. Targets was released in 1968, after the U.S. had been in Vietnam for roughly 13 years. In the film, Bobby Thompson’s character is a Vietnam veteran who was based on Charles Whitman, a military student and sniper who killed 16 people and wounded 31 people at the University of Austin Texas in 1966. Whitman shot them from a clock tower using a hunter rifle and other weapons, like Bobby in the film.

There were many other significant historical events which I think implicitly and explicitly influenced this film. In 1963, John F. Kennedy was assassinated, and like many of the victims in Targets, was shot from a distance. In 1965, 16-year-old Michael Andrew Clark opened fire on Highway 101 in Orcutt, California, and killed 3 people and wounded 10 others before committing suicide (like Bobby’s first public shooting in the film, minus the suicide). And finally, in April 1968, just four months before Targets was released, Martin Luther King Jr. was fatally shot in Memphis, Tennessee. It was a decade of bullets, bloodshed, and death from a distance.

Although it can be argued (and has been) that this film is a commentary on gun control, I don’t see it as such. To me, Targets is more about the disintegration of Bobby’s mind, his inability to communicate what was occurring within himself, and his utter disconnection from the people around him. He attempts to speak to his wife about his disturbing thoughts, but she is disinterested and brushes him off. Really, Bobby’s entire family is disinterested in each other. They live life as if playing parts on a long forgotten 1950s sitcom, and their home is completely devoid of human warmth.

Bearing in mind the political climate of the 1960s, as well as the various public shootings-from-a-distance and assassinations, the all-American murderer Bobby Thompson is a logical choice for the newer, more modern horror monster. He embodied the possibility that at any moment, perhaps while engaging in some mundane activity like seeing a film or going to the grocery store, you could be shot and killed, possibly from a great distance by someone who appears to be “normal.” You wouldn’t even know you were being targeted until it was too late. The possibility of instant death in the marketplace, on the freeway, or at a theater, elicits a state of paranoia which is, at its core, a feeling of powerlessness, and this feeling permeates Targets. Bobby kills without discrimination, because as soon as he is holding a weapon, every human being becomes a target. And because we can only sit and watch them die, we become powerless in the process.

There are many comments about the state of contemporary society peppered throughout this film. For example, when Bobby first arrives at home, a radio announces an upcoming suspense program called “Anatomy of a Murder.” Then, the reporter describes an unidentified, disheveled woman who was recently discovered. In order to explain her physical presentation and aberrant behavior, he implies she is mentally ill. This audio track is playing in the background as Bobby silently walks around his house. He observes photographs of himself in his room, listens to his mother and wife’s conversation, and paces around as if he is an intruder. The combination of the audio—the upcoming radio program focusing on murder and the eerie news report—and Bobby essentially stalking his own family creates an unsettling atmosphere. It’s already clear, long before Bobby shoots anyone, that something is deeply wrong here, both individually and collectively. Perhaps this scene implies that the psychological struggles of individuals result from society itself, which is fascinated by murder, so much so that it produces public programming analyzing both murders and murderers.

So, I do think on some level this film functions as a social commentary, but to me it doesn’t feel heavy handed, and I don’t think that is the film’s sole function or motivation. To me, Bobby’s scenes are cold, silent, and devoid of feeling, because that is how he experiences the world. (He may only experience the world this way since he returned home from war, but based on the detached coldness of his family, I doubt it is an entirely new experience.) Orlok’s scenes are warm and interpersonal because that is how he experiences and interacts with the world. Many realities populate and overlap in our world, and this film calls into question what we should do about it when these realities become violent.

Targets offers no easy answers or solutions, except perhaps that an honest confrontation is required, depicted via Orlok disarming Bobby. But ultimately, the film ends in a cold and empty silence: the vacant lot, devoid of both the audience and the film star, left only with the shooter’s empty car. After the night of terror and confusion, the morning comes with its own kind of shock; its silence and its light are sobering, and we are forced to contemplate the events we have witnessed.