Think of Marathon Man and one thing may come to mind.

Is it safe?

Yes, it’s very safe, it’s so safe you wouldn’t believe it.

Is it safe?

No, it’s not safe at all, it’s…very dangerous….

Fear of dentists, isn’t it? That’s what people say? Like this Falkirk Herald writer? “I’ve been scared of dentists ever since my childhood experience at the hands of an evil old blighter.”

I too was terrified in my childhood by my dentist. There were two things really, the pain of course but also the invasion of someone taking control of a part of your body. And a third: failure. That I had not continued the perfect set of gnashers my mother, waiting in the next room, would have hoped for.

The Marathon Man

John Schlesinger’s taut 1976 thriller stars Dustin Hoffman as “Babe,” a graduate student and avid runner, who becomes involved in his older brother’s secret-agent conspiracy.

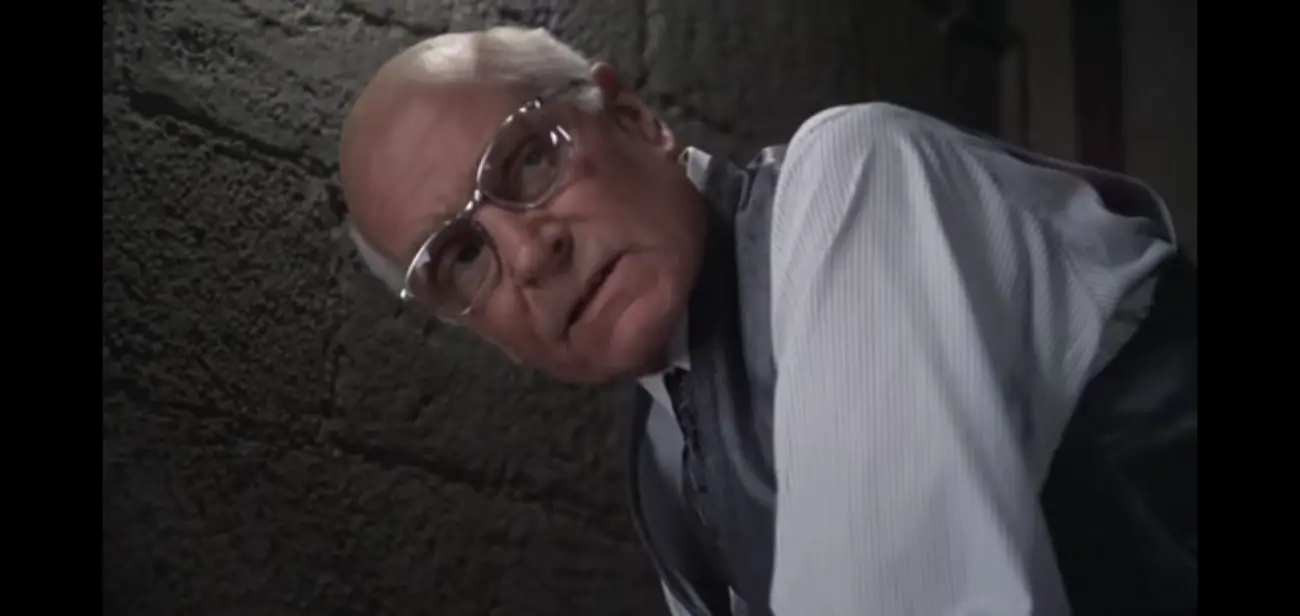

Laurence Olivier’s Dr. Szell, the other main character in the scene, doesn’t believe Babe is so innocent. It is his business not to believe. He is a Nazi war criminal, the “White Angel” of the concentration camps who is here to get his payoff, the booty he squirreled away for decades.

He wants no one to mess that up.

No One Knows Anything

It’s an iconic scene. Dustin Hoffman as ‘Babe’ Levy is interrogated in a quite particular way by Dr. Christian Szell, the Nazi war criminal, played by Laurence Olivier. And that’s it; isn’t it? Szell drills the tooth, badda bing, badda boom.

Oh no. There’s a multitude more in this less-than-ten-minute scene. And the fear for me comes from more than a fear of pain or dentists.

Babe doesn’t really know why he’s there. He knows he’s caught up in something, but he doesn’t know what. Szell needs to know what Babe knows. His future depends on it. He doesn’t know what Babe knows or doesn’t know.

And so they can’t communicate. Semiotics may be an academic study of signs and symbols and what they mean, but it’s actually used daily to facilitate a way through life. Hand signals, emojis, body language even and the most common, speech. Szell tells Babe he had alexia when he was a child, the inability to read words written down. This adds to their connection problems.

And in this Marathon Man scene they do try to connect. This is the saddest and most disturbing part of the scene. Szell knows everything about Babe’s past but nothing of his present or future. He is desperate to find out. Babe has no idea who this is and why he is here, he has nothing to go on and is desperate to find our how this works.

There’s real sadness here.

Is It Safe?

This is the line people quote from Marathon Man. Even Gremlins 2 had it (often cut out, of course) and why not? The line is odd enough to keep us coming back and beautifully done.

I had thought that Olivier added some inflection, a question perhaps, to the line. But looking back, he doesn’t. This is the brilliance of the performance. It is not a question. That would show weakness. Never ask a question you do not know the answer to. This is a statement. It’s almost a password. He isn’t asking if it’s safe, he’s giving Babe the line and expecting a response which shows he’s to be trusted.

And so the instance of the line, done quietly, the first time almost tossed casually over the shoulder as Szell scrubs up, as if this can be over with quickly. When the response is not the one he wants, the delivery remains the same but there is a sense that things are getting a little more worrying for Szell, The White Angel. His face gives away anger but also fear that this could be troublesome.

For Babe? He doesn’t understand the rules and asks for them early. He reaches out to the heavies nearby for some semiotic signal, he asks Szell to help him out. And here is the real horror. Whatever he says, he is in trouble. This is similar to the sudden question “United Or City?” from a large gentleman and his mates. Whatever you say, he can choose his response. You were in trouble as soon as they picked you out.

But the willingness Dustin Hoffman gives to the answers is so sad. As if trying to please a teacher, he tells him it is safe and that it isn’t, even embellishing with more information than he needs: “it’s so safe you wouldn’t believe it” and “it’s…very dangerous.” But he imparts the information with a resignation and a feel that he has to say this, it is by rote, there is no happy outcome.

Szell is older, in a shirt, waistcoat and tie, with well coiffed silvery hair, he doesn’t seem like an interrogator. He seems like a teacher, a family friend, a father. As Ed Atkins puts it in Artvehicle, it is “a situation that relies so heavily and so invisibly on trust.” And Babe desperately wants out of this Marathon Man scene by being a good boy, by impressing the older man. It’s pathetic, sad and extremely affecting.

They Want To Connect

Szell is interested in Babe’s learned background. He feels some similarly. And then he tells him “I would have thought you would have found me interesting.” Well, he has him strapped to chair with dental equipment in front of him. Yet still, he wants a connection.

It isn’t only him, when Szell mentions his alexia, Babe jumps in to offer a definition, like a grade A student. And Szell is temporarily impressed.

They don’t shout at each other, they converse. Szell doesn’t punch him or rough him up, quite opposite. When he first puts the dental probe into his mouth, he holds Babe’s head in an almost caressing, kindly way. And remember, when Szell puts his finger with oil of cloves into Babe’s sore mouth, he sucks on it like a baby.

There is real oddness here. They meet as two people may meet for the first time in a bar or on the train, they don’t know what rules of communication are best, so they try to find common ground. The older, more experienced one leads, trying to discover what they can build their relationship on.

It’s like Stockholm Syndrome played at double quick speed. And that’s one of the things that makes this scene so special.

Performance and Pacing

The scene has none of the London hardman sudden bursts of anger. Director Schlesinger is too savvy for that. The scene is played with a slow pace: the horror unfolds and that adds to the feeling that Babe and we too don’t know what will happen next. If you’ve seen a bloke shout in your face and punch you in the nose, you know you’re in for more of that.

Here, we have no idea. The room is a rather antiseptic white, but that isn’t a giveaway. Szell takes his time to open his case and wash his hands before the repetition of “Is it safe?” This is not a barrage, it’s a conversation. And even when the dental implements come out, it isn’t an interrogation. You’d expect the pain to begin immediately, but Szell undertakes a dental check up, softly upbraiding Babe on the state of his teeth.

This lulling makes the moment when he shoves the hook into his teeth so much more shocking. But it’s not done to inflict pain, it’s done to set up a gentle life lesson, oil of cloves will sooth. And so it is a choice, between that and discomfort.

Don’t forget, this isn’t a continuous scene. The “getting to know you” section is some time later, after Babe has slept. And in this part, Szell is keen to tell Babe what he’s going to do with him. They’ve begun to bond, it shows the interrogator knows his business and Babe is safe in his hands, oddly. It also allows Babe a sight of what is to come, he knows there will be pain, but it’s the not knowing which is the worst thing. And that adds some sweetness which crashes against the usual interrogation scene.

There are some lovely moments in the dental scenes, Szell’s first question is at the basin behind him, so Babe can’t quite see him. You might have thought that the dental equipment being revealed may dissipate the tension, but we don’t know which instrument is to be used. But some of the most frightening moments are unseen. Why? They take place behind an open case, in fact we are introduced the drill by just the sound of the motor whirring—it’s genuinely disquieting.

The performances? Olivier is quietly avuncular, keen to make an impression on this young man who he has limited time with. He wants to speak to an intellectual nearly, if not equal and he has an interest in his work that so many have. In a performance so full of craven desire and twitchy fear, this just pulls the curtain back.

Hoffman wants to be liked. Because it will ensure his survival of course, but also because he sees a man who is older and seemingly more experienced than him. It’s a coming of age, the whole film, for Babe. Hoffman allows that to happen, he’s a fish out of water and the results are often frightening.

Some Of The Artistry Of The Scene

Schlesinger and his cinematographer Conrad Hall knew exactly how to wring every ounce of fear out of this.

Firstly, the setting. If this was all gleaming white tiled walls, you would feel safe. You may feel ill at ease, but this would be clearly a doctor or dentist’s set up.

That certainty isn’t allowed. This has white walls, which may make you feel sanitised, but it is unused, dirty, grubby. Something is off here.

Then there is the placement of the two main characters. Babe is in his chair in the middle of the room. He can see what is in front of him, but what will happen behind him?

Szell is placed just on the corner of his vision at first. Babe can’t quite see him, strains to make him out. This is essential for the asking of the statement “Is It Safe?” When Babe answers, he cannot see the reaction from his interrogator. He lacks the essential semicolons and has no way to control, or even take part in, the dialogue.

The camera takes both sides. It lingers on the NAZI Szell, giving him time to establish himself, almost asking us the question ‘doesn’t he seem avuncular to you?’

On the other side, it swoops into Babe, pretty much as he may expect his attackers to, quickly closing in on him, affording him no breathing space and brusquely closing in on the rolled up instrument bag, Babe is left out of focus behind.

All this is unsettling. As are the sounds of preparation just at the corners of our hearing. Our dentist makes preparations out of our vision and then comes at us with little soothing pause.

This scene does the same.

One Of Those Scenes

There so many other scenes in this superb movie, including Olivier’s childlike delight in seeing the diamonds and shortly later when he is recognised in the street as the Nazi, called and and pursued, my favourite here.

But this scene is iconic. It stays with you. It’s up there. It’s frightening. And there many more reasons other than childhood fear of dentists and pain.

This Marathon Man scene is all about the fear of rejection. Is it safe? Sometimes not…

Superb? Not by a long shot. Poor storytelling and offensive brutality. Probably Schlesinger’s worst picture. A commercial hack job.