By 1995 Primal Scream were a joke. The poor reaction to the retro 70s rock of 1994’s Give Up But Don’t Give Out gave credence to the running gag that the Scream were just chancers.The theory went that the success of Screamadelica was due to the production by cutting edge DJs like Andrew Weatherall and mixing by The Orb, who merged the Primal Scream’s retro sounds with rave. Although gobshite frontman Bobby Gillespie loved to spout on about how his band are the best rock and roll band in the world, they undermined that sentiment by overhauling their sound with every album. The Scream just happened to be the right band in the right place at the right time, but now that time that run out.

Their love of drugs was legendary but the band’s behaviour reached a cartoonish extreme when they refused to appear on Britain’s biggest music show, Top of the Pops, because flying into Luton Airport wasn’t “rock and roll” enough. Which may have made sense if they were Guns N’ Roses (or still commercially viable) but their last two songs hadn’t even charted in the UK Top 20. When the inevitable Rod Stewart cover of “Rocks” came out in 1998 it was a sign of how far this once innovative band had fallen during this period. A drug-fueled American Tour (was there any other kind in the 90s?) brought the band close to splitting. Returning home, the band needed time apart and a rethink.

Whilst the nation were preoccupied with the Britpop Wars in 1995, Primal Scream plotted a darker twist on their previous indie-dance sound. The first sign change afoot was the heavy dub of the stand alone single, “The Man and the Scream Team Meet the Barmy Army Uptown”, a collaboration with Irvine Welsh and U-Sound, which turns the football terrace chants of “Who are ya?” into eerie performance art. They took things even further out there with their 1996 contribution to the Trainspotting soundtrack, transposing the sprightly funk of Curtis Mayfield’s Superfly soundtrack to a paranoid crawl around the grey tower blocks of Edinburgh. It’s nearly 9 minutes of echoing timpani drums, police sirens, and disconcerting whistling. Compared to the other acts on the soundtrack, it sounded more akin to the shimmering ambience of Brian Eno than their indie contemporaries, Pulp and Sleeper.

For a teenager like me, raised on a mix of Baggy, Trip hop, De La Soul, Genesis, Grunge, and Britpop, and with only a handful of albums to my name, including the seminal Trainspotting soundtrack, that instrumental sounded like nothing else. A whole universe of Dub, Funk, Underground Dance, and Soul was about to open up. I was keen to hear what came next…and then in 1997 “Kowalski” dropped.

The Doppler effect and the soft meowing keys invited me in before the jackbooting drums and the incessant bass groove blew the track wide open. “Kowalski” doesn’t so much develop as handbrake turn between Bobby Gillespie’s ominous whispering “like a butterfly on a pin, soul on ice” and guitarist Robert “Throb” Young’s screeching guitar. The interspersed dialogue from the original Vanishing Point film revels in celebrating the main protagonist’s anti-hero credentials, and the unsubtle double meanings in the script: “Speed means freedom of the soul.” It’s a dark joyride through the counterculture with all the musical trappings of 90s electronic music garlanded around it, without any of the nasty homophobic or sexist baggage that makes the original film unwatchable.

In retrospect, “Kowalski”’s nihilistic message of the “blue meanies” coming to stop your fun plays as a direct counterpoint to the joyful hedonism of “Loaded”—yeah, you can have your fun but the man will come for you…eventually. To me, this sounded like pure rebel music.

The second single, “Star”, doubled down on these themes with some smooth dub-soul. Gillespie pays homage to Black Civil rights heroes whilst the push and pull between Augustus Pablo’s whistling melodica and Pandit Dinesh’s rhythmic tabla capture both the cheerful optimism and the melancholy reality of the struggle. In my comfortable bubble of being a 16-year-old white boy on an estate in the middle of England, the track sounded like retro homage. 25 years later—and wiser—the lines about freedom fighters and terrorists being indistinguishable sounds frighteningly prescient.

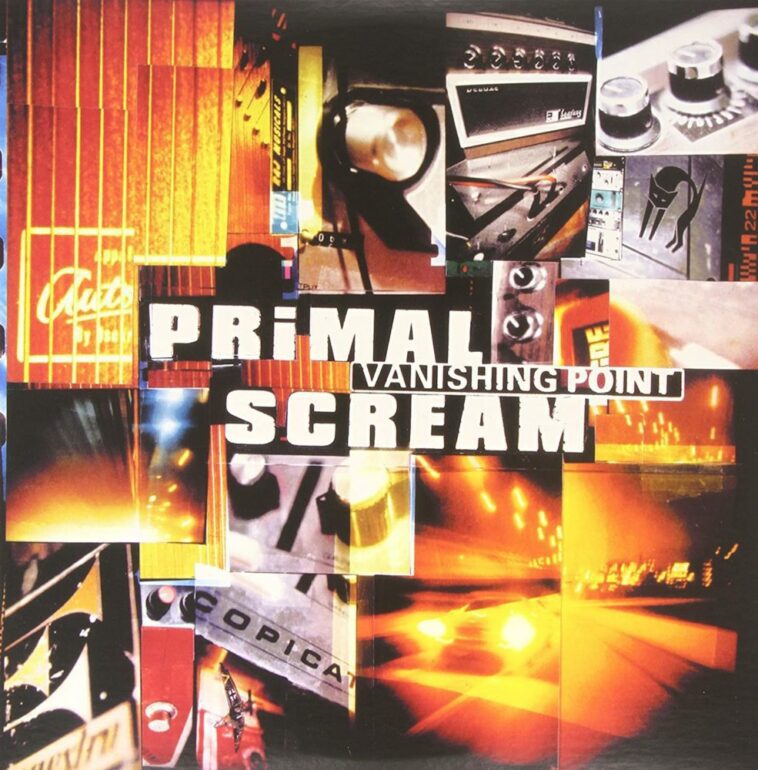

From the moment I got a hold of the album, put it into my friend’s 80s stereo, and felt the bass rumble intro shake the floor, it was clear Vanishing Point’s intention was to unsettle the listener. The inside sleeve summed up the mood of the album with one mantra: paranoia is total awareness.

That bass rumble segues into a false dawn of synthetic bird song and soaring sitar effects, like a brief sarcastic nod to Screamadelica’s musical euphoria. All seems well until Marco Nelson’s driving bass kicks in, and then “Burning Wheel”’s dark night of the soul truly begins. Like The Doors underscored by krautrock: Throb’s guitar shudders anxiously throughout, floating above the backwards phasing, always threatening to be cast adrift. The track then unspools itself into a jazzy haze, briefly reprising itself shorn of all production tricks and slowly fades out. It’s a busy opener, and one that makes exciting virtue of the Scream’s chameleon-like ability to jump from style to style. They could no longer be called dilettantes—they were going all in here.

Intended as an alternative soundtrack to the original film, 3 instrumentals flesh out the album’s cinematic ambition. The aforementioned “Trainspotting” fits in snugly alongside “Get Duffy”’s 70’s cop show dub ambience and “If You Move Kill Them”’s swaggering Miles Davies strut. Rather then just filler, the restless movement of these tracks brings some much needed light to an otherwise claustrophobic album.

The album’s centrepiece, “Out of the Void”, throws the listener into the terrifying stasis of a drug addict coming down; too tired to sleep and too hungry to eat. It acts as a riposte to the Screamadelica track, “I’m Coming Down”, which glorified the maddening contradictions of drug abuse with the smug air of this all being part of the process. On “Out of the Void”, the highs that the addict wished for are distant memories, leaving nothing but bitterness.

That numbness pervades “Stuka”’s deep bass drops, with Gillespie’s usually strident voice distorted into a monotonous robotic rasp, which has the peculiar effect of making him sound uncharacteristically vulnerable. The track is an ever-shifting whirlwind of whirring keys and urban noises, with a pensive bassline trying to skulk away underneath it all. Listening back, the final coda of “if you play with fire you’re gonna get burned, some of my friends are gonna die young” has greater poignancy in the wake of Throb’s untimely passing in 2016 due to alcohol and drug misuse.

“Medication” feels like an outlier: a fun linear rocker whose flippancy sounds off-message with the rest of the album. Ironically, had the Scream lived up to their reputation of farming out tracks to outside producers then perhaps Adrian Sherwood’s superior remix of “Medication”—named “Dub in Vain” on the Vanishing Point remix album, Echo Dek—could have made the cut. That mix has the brutal propulsion of the Stooges fronting a jazz band. The track we have here sounds like a Sex Pistols knock-off—albeit quite deliberately so, as Glen Matlock is on hand to play bass.

Decidedly on point is “Motörhead”, a brutal techno warping of the metal band’s self-named track. It’s a maximalist assault on the senses that sounds not dissimilar to Digital Hardcore band Atari Teenage Riot. Listening to it at full volume with my dad’s headphones on was an out-of-body experience. It also taught me a valuable lesson: great music will get you high without any medical assistance. You just need great headphones.

Time slows to a near halt over the drawn-out chimes of closer, “Long Life.” Gillespie mutters platitudes to himself as the drugs take hold. Rather than the false dawn promised by the opener, it feels like the last.

1997 was a year marked by British bands releasing melancholic comedown albums-–Blur, Supergrass, The Verve—all of which pushed these groups to be more creative. Vanishing Point, however, cast the widest net, and in doing so sent me down a path to discover bands and artists as varied as the MC5, Lee Scratch Perry, Miles Davis, Aphex Twin, and Neu. It was my gateway album to new genres and new possibilities. These influences were expertly curated by the band (and producers Brendan Lynch and Andrew Weatherall) into perhaps the most sincere album of the Scream’s career: one that reflects their lived experience of drug culture. Their bombastic follow-up album, XTRMNTR, shouted louder and put Gillespie back at the forefront, yet Vanishing Point is a richer and denser work for letting the whole group find their voice.

After Vanishing Point, there was no longer any doubt that Primal Scream could finally walk it like they talked it. The joke was on us for ever doubting them.