As I’ve been noting in my recent series of “On the Scene” essays, editing in documentary typically serves either an expository or an argumentative purpose. An editor might, like the opening scenes in Salesman or Minding the Gap, open with a scene that not only establishes a setting and character but also introduces one or more of the film’s key themes. Or, in the case of The Beatles: Get Back, footage might be edited less to provide exposition than to argue a point of view, as when George Harrison is shown to stew while his bandmates cavort. Another famous example of the same is when in The Thin Blue Line Errol Morris cut from a dubious eyewitness to archival clips of detective films to undercut her testimony.

But occasionally, a documentary editor will juxtapose dozens—or hundreds!—of individual images and sounds to compress time and create an effect that is more expressive, or even poetic, than it is expository or argumentative. In the tradition of the Russian filmmaker and theorist Sergei Eisenstein, the use of montage can seem more rare in documentary than in fiction filmmaking, but its use can allow filmmakers to compress time, evoke mood, and create associations. I can think of few films that do so as emphatically than the compelling, extraordinary film Tarnation (2003), directed by Jonathan Caouette, especially in its scene characterizing the subject Jonathan’s mother Renee’s descent into mental illness, set to the music of “Wichita Lineman.”

Tarnation’s impact on documentary filmmaking is already well-charted. While in his late 20s, Caouette, an actor from Tarnation, Texas and living in New York City, assembled a homemade cut using an archive of still photos, self-recordings, home videos, his own early attempts at filmmaking, other audio and written texts, and contemporary interviews with his mother and grandfather, all charting his own growth through mental illness, neglect, and abuse as well as the trauma of his mother. Renee, a former model who rose to a level of fame and glamour, descended into severe mental illness following trauma and electroshock therapy, and she and her family experienced multiple kinds of dysfunction over generations and decades.

Obviously, the content of Tarnation will make it a difficult watch for anyone triggered by abuse or trauma. But its making was a therapeutic act for Jonathan, who took from his and his mother’s often-recorded lives a trove of mundane clips, shards of experience, cultural flotsam, and disturbed family reminiscence and edited them into a multigenerational story about catastrophe and survival. Borrowing his boyfriend’s computer, Jonathan used its iMovie software, itself then a nearly-new phenomenon, to assemble the film, employing many of its feature sets for split-and-multiple screens, filters, and effects. For a reported $218, Caouette was able to create a work of intensely personal, highly ambitious, and individually expressive art that examined intergenerational transmissions of trauma, identity, gender, sexuality, and creativity.

Tarnation begins in Caouette’s present as the adult Jonathan lives in New York City with his boyfriend. But soon he learns his mother, Renee, a former model living back home with her sickly father Adolph, has overdosed on lithium. In the wake of her earlier drug abuse, psychotherapy, and institutionalization, Renee faces additional brain damage. Jonathan brings his mother back to New York with him to recuperate and begins to reflect upon their long and difficult journey together: and so this scene, telling the story of an important period together in their lives, from 1977-1979, begins.

As the first earthy guitar notes of “Wichita Lineman” begin, an image of a young, shirtless, cavorting Jonathan is replaced by several close-ups of his mother Renee in her youthful glamour-model beauty. Each of these images pulses subtly with a strobe effect that will continue through much of the sequence. Slightly lower in the audio mix, Renee’s voice is heard in what sounds like everyday conversation but is undecipherable; another layer of sound design adding to an already complex mix. As Glen Campbell’s voice begins—“I am a lineman for the county…”—Caouette’s non-diegetic text provides some explicit narration of its own.

The story told by the on-screen narration is blunt, terse, and traumatic, remaining onscreen nearly every second of the sequence. I’ll replicate it here in its entirety, then circle back to its synchronization with the images, cuts, music, and other sounds it accompanies:

“In the winter of 1977, Adolph’s grocery store burnt down. Renee, in a psychotic state, took Jonathan to Chicago with no money and no place to stay. The two immediately encountered trouble. Renee was raped in front of Jonathan by a man who picked them up off the street. Renee called Adolph to wire them money to come home on a Greyhound bus. A few hours into the trip Renee and Jonathan were kicked off the bus. Renee was disturbing the passengers.

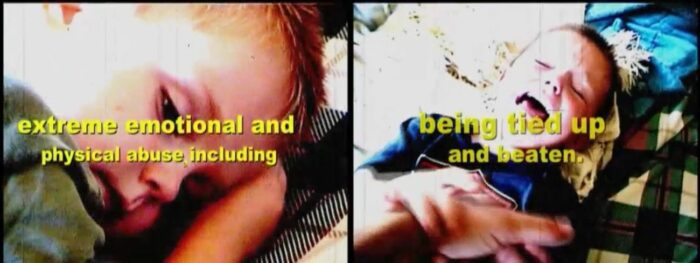

Jonathan was placed in a foster home for six weeks in Marion, Illinois. Upon arriving back in Texas, Jonathan was removed from Rosemary and Adolph by Child Welfare and placed in Texas foster homes for the course of two years. In foster care, Jonathan was subjected to extreme emotional and physical abuse, including being tied up and beaten by his foster parents. Jonathan was four years old.

Meanwhile, Adolph and Rosemary signed a new consent form for Renee to continue with shock treatments. Upon the last treatment, there was little sign of Renee’s original personality or state of mind. Renee was 25 years old. Rosemary and Adolph got custody of Jonathan in 1979. While in foster care Jonathan’s memory of Renee had receded. Renee remained in The Austin State Hospital from 1977 to 1980.”

The blunt, factual reportage of this traumatic period in Jonathan and Renee’s lives serves as the expository backbone of the sequence. Indeed, it’s more than a little unusual for onscreen text narration to occupy more than half of a scene’s running time. But while the text itself may chart, in its terse, unadorned style, what happened, it does little to convey any emotion or sensation of those events. Rather, Caouette and co-editor Brian A Kates’ inventive editing, manipulating image and sound alongside those words, makes the sequence almost unbearably moving.

Most of Tarnation’s imagery is pulled from archival home video and family photos, and this scene is no exception. The images are not ones necessarily synchronized to the narration—that is to say, there is no footage of the bus incident or Jonathan’s actual abuse—but they are often chosen to accompany that text. For instance, the mention of Jonathan’s abuse is accompanied by an image of him (playfully) screaming. The images are often, at the scene’s most charged moments, split into two, four, six, nine, sixteen, and sometimes more, sometimes mirrored, suggesting a dissociative or bipolar condition emphasized further by a strobing effect that becomes, as the scene progresses, more and more pronounced.

While the scene plays the entirety of “Wichita Lineman” without any distortion or editing, its sound design includes a collage of distorted, fragmented voices. Mostly, we are given to assume, these are Renee’s: they are echoed, distant, eerie, disjointed, entirely separate and asynchronous from any video image and entirely discordant with the mellifluous, gentle plaint of the song. The scene reaches its climax when it describes Renee’s shock treatments: archival photos of young Renee as a model and as a mother are cross-cut with video of an anguished young woman crying in the rain. The song crescendos and fades as bursts of white noise accompany the increasingly intense images of the woman. (There is no indication of what this particular image actually is, though it may be Renee performing in one of young Jonathan’s scripted films.)

Even when the last notes of “Wichita Lineman” subside, the sound collage continues and the images proliferate at an even unprecedented rate, so fast at this stage, they can barely be processed. It’s as if the filmmaker’s memory can no longer cope with the trauma it’s recalling: glimpses of young Jonathan, his family, and others flicker by so quickly that the memory of any individual moment is subordinate to the larger, more traumatic truth of his ongoing foster care and the subsequent abuse he experienced there.

That Caouette would choose, of all songs, “Wichita Lineman” for a sequence that narrates a period of trauma, abandonment, and abuse seems, on the surface, practically inexplicable. Its lyrics feature none of the above. Its languid pace and gentle tones seem completely opposite from the frenetic pace and fragmented imagery of the scene’s content. Written by Jimmy Webb, the song was solicited by Campbell: “Do you think you could write us another ‘By the Time I Get to Phoenix’?” he asked the songwriter bluntly on the phone, as if ordering from a catalog. Webb had an idea for a similarly geographic plaint inspired by a single image of an actual lineman—a county employee—working the telephone wire. Within hours he had what he thought was a promising, if unfinished, draft, lacking a third verse.

Campbell was so pleased he set about recording the song immediately, even without a conventional third verse, and the result was a(nother) million-seller. Bob Dylan once called “Wichita Lineman” “the greatest song ever written,” and whether one agrees with his assessment, the song was selected by the U.S. Library of Congress for inclusion in the National Recording Registry in 2020. Though today more than 50 years old—and its signature performer having passed on—it’s a song that remains famous for its melancholy, wistful tone and focus on the everyday story of a person quietly trying to hold together his emotions in a moment of anguish. It was more than a million-seller: it was a song that felt intensely personal for any listener who experienced isolation or loneliness.

The song’s popularity did not wane in the 1970s, and among those fond of it was a young Jonathan Caouette, as he told Film Journal in 2004:

I used to climb up in the back of my grandparents’ car, one of those old Chevrolets from the ’70s. I was like four or five years old and I would crawl up where the speakers are in the back seat—you know, with the little lip? I would climb up on the lip and we would be driving from Galveston to Houston or whatever, and I would just fall asleep with my ear to the speaker and I would always hear that song for some reason. It was so personal to me, even though it has no real linear leverage in the film. It’s a very sappy, empathetic, beautiful song that I think still works for the scene—it’s sort of about people trying to communicate and get in touch with each other.

For a film made by a novice on a home computer using iMovie, the art and technique here are remarkable. Not too long before Tarnation was made, editing was a matter of cutting and splicing filmstrips with tape and paste. The computer—even an early Mac like Caouette is using here—opens up a world of possibilities. Though “Wichita Lineman” is wistful, loving, pastoral, and gentle, it’s very much at odds tonally with the incredibly fast-paced montage and collage of images, words, and sounds, many of them fragmented and multiplied in ways that are intended to provide a visual metaphor for dissociative schizophrenia disorder and with bursts and flashes of images serving as metaphors for the shock treatment poor Renee endured.

That Caouette could manage this, being as he was self-taught with rudimentary technology, makes for a fascinating sequence, an example of what Eisenstein called tonal montage, aimed at evoking sensation or emotion. The impact of those images is amplified by the complex sound design, full of fragments and flotsam of audio calls, static, screams, and everyday verbal interaction. The credits of the version of the home media release of the film indicate its postproduction sound was provided by Skywalker Sound, a division of LucasFilm; that version could be distributed only after its investors paid the rights for “Wichita Lineman” and the other music that’s used here. (Those rights inflated the film’s distribution budget to over $400,000, well beyond Caouette’s means.) Nonetheless, the technique conveys the raw emotion and pain he and his mother experienced—and in a way that simply would not have been possible a scant decade before.

As Tarnation is mostly “about” the filmmaker Jonathan Caouette himself, it became more performative than participatory. In the performative mode, the filmmaker him (or her or their) self becomes the subject of the film. Caouette’s was one of many such personal films that became increasingly popular and commonplace in recent decades in ways that didn’t exist before desktop editing software and iPhones. In fact, the very existence of YouTube and TikTok—subjects turning their cameras on themselves to chart their lives for others—is predicated by the work of films like Tarnation.

But Tarnation is also poetic—especially in the early iMovie montages, split-screens, color effects, and other devices Caouette uses that aim to create analogues of acid trips and schizophrenic breakdowns. The “Wichita Lineman” sequence is just one of its many examples. Uncannily visually and sonically expressive, it uses cinematic techniques to convey mental and emotional turmoil, anguish, instability, and even joy. Tarnation is remarkable for using such simple software to express such complex personal relationships and emotions.

Some viewers will be and have been uncomfortable with the film’s depiction of mental illness, but Tarnation depicts the life that Jonathan and Renee together endured. Caouette used the profits from Tarnation to purchase his mother both a house and long-term care. Later, he made a second film, Walk Away Renee, also about her. During the events of Tarnation Renee is remarkably unwell, as a consequence of injury, electroshock therapy, abuse, and dependency. Viewers might question the ethics of Jonathan’s depicting these events when Renee is in no position to give consent, but I am unsure what Jonathan might have done for her other than the largely palliative care he provided her after the film made its success.

Without, of course, Jonathan’s willingness to film himself and divulge the traumatic details of his and his mother’s lives, there would simply be no film. His willingness to do so and inventiveness in his approach made Tarnation a phenomenon and a historically important film. It didn’t lead to the kind of career an Errol Morris or D. A. Pennebaker enjoyed, but it did create a new space in documentary filmmaking for intensely personal, performative filmmaking. While the film has on occasion been feted at recent festivals and enjoyed a run on The Criterion Channel, its availability is limited. Nonetheless—and despite its now-dated iMovie aesthetic—Tarnation remains, if you can find a copy to view, a ground-breaking, visually evocative, and profoundly moving arthouse documentary, a testament to a son’s love for his mother and the trauma she faced.

Tarnation is by far one of my absolute favorite films of all time. Completely relatable in ways, and throughout my own youth I’d wondered how to communicate artistically what I’d experienced. When I saw Tarnation, I felt like Jonathan Caouette crawled into my brain, ate it, then threw up an entrancing kaleidoscope of definitions. Finally, there was a way for people to understand and maybe truly empathize, with realities that so many children, and families live. He did it! He did it perfectly! Thank you for bringing up his film. I always encourage people that I know to see it. Also, thank you for the insight on The Wichita Lineman connection.

Katie, thank you for reading Film Obsessive and taking the time to reply. My personal experience isn’t anything unlike Caouette’s, but I can appreciate how his work has resonated with others whose might be more similar. I wish it were more available for people to see! Sadly, it’s still unavailable to stream.