Sofia Coppola’s 2010 Somewhere opens with an unnervingly static shot framing a portion of a desert oval racetrack. A Ferrari coupe takes a half-dozen laps, each time exiting the frame and then re-entering it at the same positions. The barren desert earth is nearly the same hue as the ashen gray clouds above. After a full 95 seconds of this unbroken take, the Ferrari once again enters view, slows and stops, and a young(ish) man in jeans and sunglasses—we’ll learn soon he is actor Johnny Marco, played by Stephen Dorff—exits and stares, nearly immobilized by the scope of his surroundings.

That first shot of the film ends up, uncut and without movement, nearly two minutes long! Its character’s actions are entirely circular, aimless even, apparently without purpose or direction, an empty exercise conveyed without artifice. Another director might have cut this scene with music, close-ups, quick cuts, Foley effects, or other means of artificially heightening a Bullitt-like careen through the arid desert. But Coppola, known for her debut The Virgin Suicides, the languid surprise hit Lost in Translation, and its underrated follow-up Marie Antoinette, has something entirely different in mind with Somewhere, the story of Johnny Marco’s torporific stardom and strained familial relationships.

Somewhere is if anything about ennui and torpor in modern Hollywood. Marco, who injures himself falling down a set of stairs at a party in the film’s second sequence, is a rudderless actor spending his days recuperating at the famed Chateau Marmont, wasting his days and nights with strippers and booze while grudgingly fulfilling a handful of press obligations. When his ex-wife is unable to care for their daughter, eleven-year-old Cleo (Elle Fanning), Marco takes on a set of new-to-him responsibilities that reintroduce him to his charming, maturing daughter and cause him to question his lifestyle.

That first scene of Somewhere is intended to train its viewers what to expect from the rest of the film. And while it’s true that Coppola will at times move the camera or cut during a scene, Somewhere employs an incredibly slow, languid, and yes, torporific pace of editing and minimalistic camerawork that conveys the slow drudge of midlevel celebrity. It’s the antithesis of a loud, buzzy, violent film like Tarantino’s later Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, which closed out the same decade Somewhere rang in: there are no crazed acolytes of cult leaders, no fights or flamethrowers, but instead, just the slow crawl of misspent nights and hungover days.

Somewhere might also be read as something of a reaction on Coppola’s behalf to the initial critical rejection of Marie Antoinette, a film reviewers initially disparaged as anachronistic and ahistorical, with ill-suited music, MTV-style montage sequences, and creative license. (With a bit greater critical distance, the film’s reputation seems today much stronger, its influence on contemporary feminist-revisionist streaming series The Great and Dickinson more than a little apparent.) Somewhere leaves behind a studied history and fact-based narrative for a fiction more rooted in the experience Coppola herself knew as the offspring of Hollywood royalty; more to the point, it abandons the brash technique and montage editing of Marie Antoinette for an approach that conveys every anguished, languid minute of Johnny Marco’s ongoing ennui.

To do so, Coppola lets each scene play out in full. Whether Johnny is prowling aimlessly in his Ferrari, entertaining a pair of strippers, initiating sex with a party hookup, or stumbling through a press conference, Coppola allows us to suffer through each agonizing minute. Johnny can’t get aroused by strippers, can’t stay conscious enough to perform, and can’t answer the press’s questions about “postmodern globalism.” But there’s a method here, and Coppola is nothing but consistent. For instance, when Johnny takes Cleo to her figure skating lesson, he strikes up the same kind of dithering, innocuous dialogue he does at his parties, asking her how long she’s been skating: as the sequence unfolds, and we (and he) watch Cleo practice for over three minutes, it’s clear he has little clue about his daughter or the life she’s been living. She’s quite good—and been at it for some time.

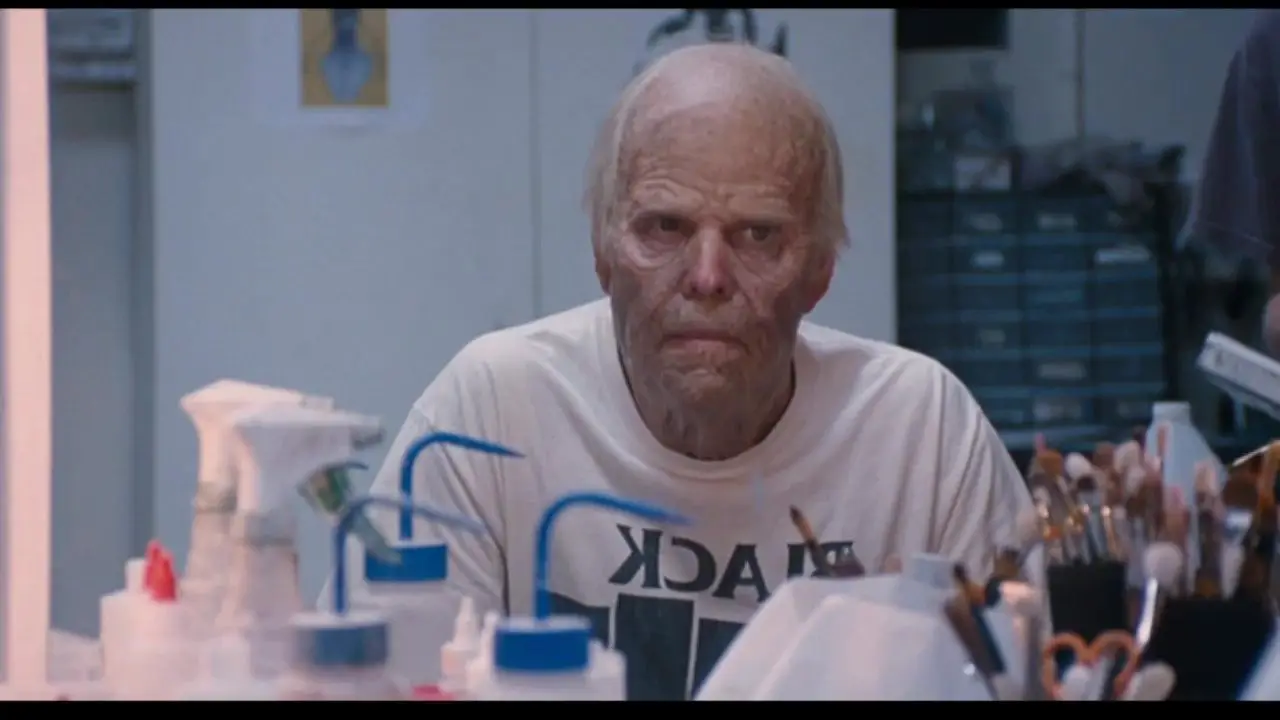

Later, at a makeup session, Johnny is instructed to wear a plaster cast covering his full head, save for nostril holes for him to breathe. Coppola exploits the same long, slow burn to show him, in full-face plaster, for a full 95 seconds in long take, the only movement an infinitesimally slow dolly-in, the only sound his labored breathing and the faint hum of ventilation. He’s reduced, here, to a blob, sans visage, a prop like the other masks and busts on the shelves behind him. The long take feels as suffocating as a full-face plaster cast, but it’s also richly, subtly humorous, a telling sign of the indignities actors face, a long-standing trope of the Hollywood-on-Hollywood film.

The result of the work, though, is pure Hollywood magic: Johnny is transformed into an eighty-year-old version of himself. A mirror sequence—the second of three in the film—presents the actor with a glimpse at his future. In Sunset Blvd and The Star, aging actresses confronted the constant indignities of the Dream Factory’s relentless (and gender-biased) ageism. Johnny may seem clueless in comparison to a Nora Desmond or Margaret Elliot, but he’s not so dim as to be unable to process what his aged mirror-image might mean: he won’t be able to survive on his good looks and sullen affect for long.

Johnny’s not the only one confronted by the realities of time in Somewhere. His daughter Cleo is—though less often onscreen—ageing too, navigating a world new to her with an absent mom and no father. Fanning clearly adores the opportunity to spend any time at all with her long-missing-in-action dad, even if it’s just having him in the bleachers during her skating practice. Most of their time together consists of them playing Guitar Hero V or Wii Tennis and her practicing her domestic skills. Johnny has little clue how to engage Cleo in any kind of earnest dialogue, but both of them are able to enjoy each other’s company, even on a public-relations junket to Italy.

There, the press is eager to fete Johnny with a Telegatto award, but that they are unfamiliar with Cleo suggests his daughter simply isn’t a part of his public life to that point. In other words, for the sake of his career, he’s pretended she doesn’t exist. While Johnny enjoys Cleo’s company, he’s still unable to manage his own relationships: at a breakfast in Milan, Cleo and one of Johnny’s sex partners share an uneasy breakfast together. The gal-pal asks several pressing questions, each of them a bit too advanced for eleven-year-old Cleo: “Do you drink coffee? Do you have a boyfriend?” Cleo can partake in the trappings of her father’s celebrity but, it seems, not her father’s full attention. Cleo’s silent glare is telling—she’s unhappy with having to share her father’s attention—but the actor remains, apparently, oblivious to her feelings.

Still, the father-daughter relationship constitutes much of Somewhere’s charm. Coppola has noted that the film isn’t autobiographical per se: while the director grew up outside Hollywood in the Napa Valley and was close to her father Francis Coppola, the character of Cleo was based on the daughter of a friend. Still, some of the scenes in Somewhere sprung from Coppola’s direct experience, such as sampling gelato in Milan. “My dad was excited to let me be in worlds that kids don’t usually go to. My parents always took us out to the Academy Awards starting when I was probably 8 — things that people don’t usually go to,” she recalls.

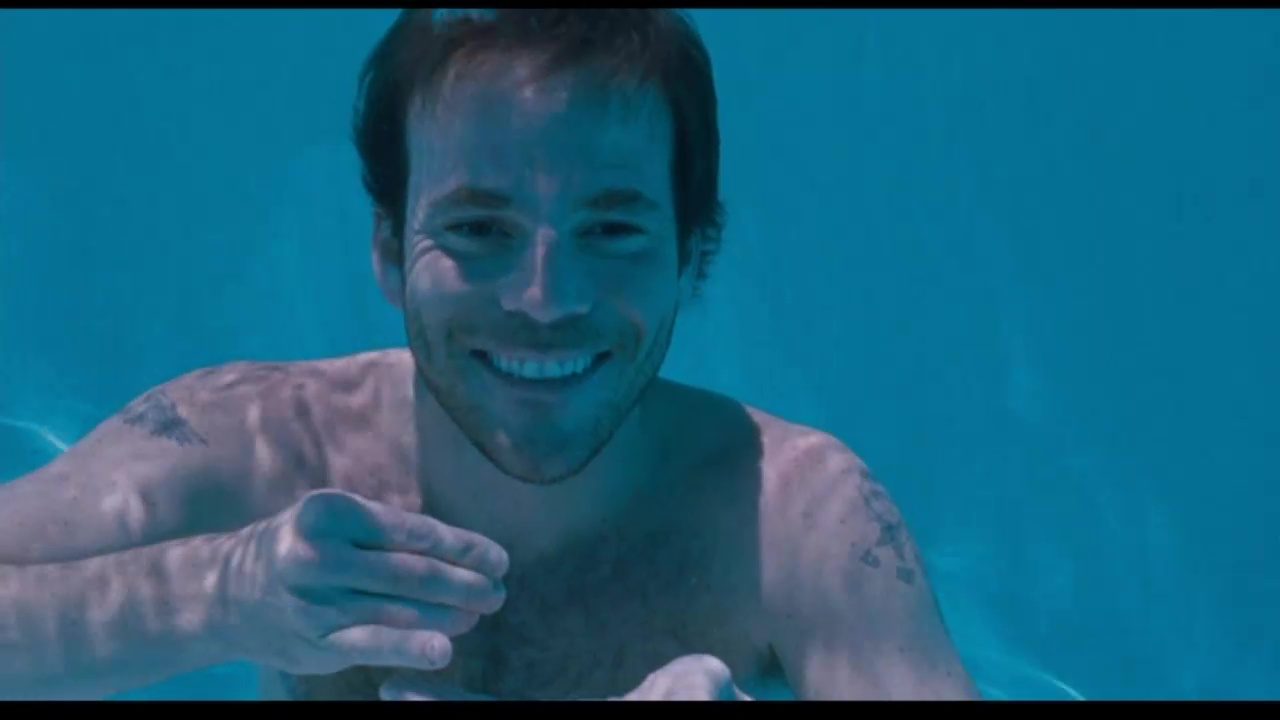

Back stateside, Johnny and Cleo return to the Marmont, where they are serenaded with a version of “Teddy Bear” by a local guitarist. (That’s a song used with some malice in the re-release of Dennis Hopper’s 1980 Out of the Blue, another film charting the life of a young girl navigating adolescence with a newly-returned father figure—if much more devastating results.) The two enjoy some pool time, and underwater, away from all the expectations and pressures of Johnny’s career, the actor finds himself free to break a broad smile, as if he’s finally found himself in his true element.

But the two are just playing, playing at underwater tea-time and in essence, playing at a make-believe version of what a father-daughter relationship might actually entail. And those require more than bouts of Rockstar, bites of gelato, or dainty sips of underwater tea. One of Coppola’s long takes concludes the scene as Johnny and Cleo sun themselves, oblivious to the others around them: here Coppola dollies out slowly over the course of the shot to reveal the other poolgoers around them while the two enjoy each other’s silent company on their last day together.

Those extremely long takes—the 95-second opening, the similarly-long plaster-cast shot, and this nearly-two-minute take—run Somewhere’s Average Shot Length, or ASL, to nearly 16 seconds. Over the course of its 97-minute run time Vashi Visuals counts 376 individual shots. Average Shot Length, as David Bordwell notes, is at best a blunt instrument for measuring a film’s pace, and here Coppola employs several individual shots lasting over 90 seconds. But by comparison, Coppola’s prior film Marie Antoinette, with scenes like its “I Want Candy” montage of clothes, cake, and candies, charted an average shot length of 5.4. (While over the decades ASLs have steadily decreased, by 2010, action films like The A-Team and even a comedy like Date Night had ASLs of under 3.) An ASL of 15.5 is astonishingly long for a modern motion picture.

The main point of such calculation, though, is not to reduce Somewhere to numbers but simply to reinforce how Coppola weds style to substance. Those extremely long takes evolve over the course of the film, from Johnny’s aimless, circuitous motion driving to his stultifying entrapment in makeup to something more peaceful and transcendent. In the final long take of him and Cleo peacefully enjoying the Marmont poolside, Coppola registers an ethereal moment of silent bonding, the two of them oblivious to the others around them and simply enjoying a last day together as father and daughter.

That long take of rapturous silence provides the two some solace from Johnny’s wild life and Cleo’s scheduled activities. However, it doesn’t directly address what Cleo needs most. In the Ferrari on the way to summer camp, her time with her father nearly over, she finally breaks down: “I don’t know when she’s coming back, and you’re always gone.” Johnny has no answer—only more games, this time at a casino before she leaves.

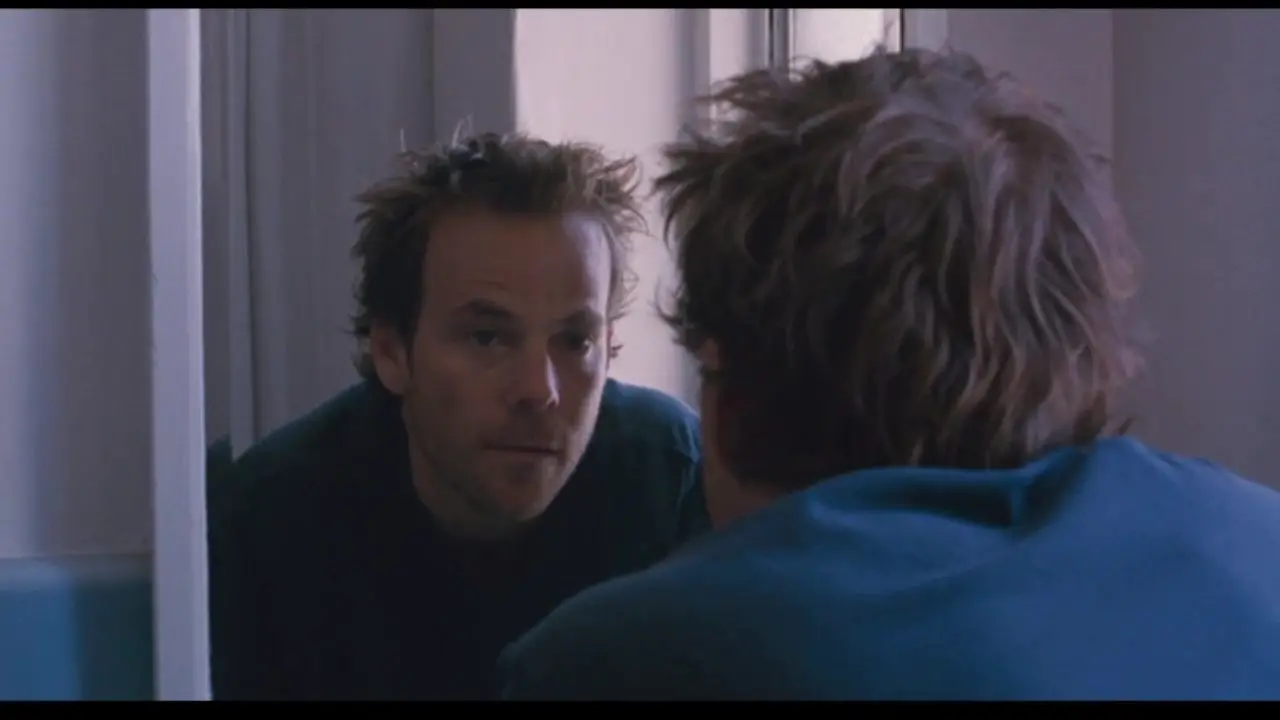

Alone and back at the Marmont, Coppola employs one more mirror scene, the third such in the film, and like all mirror scenes an opportunity for reflection. In the first Johnny examined himself drunk, post-accident; in the second, in full old-age makeup, as a future version of his elder self. In this scene, Johnny is sober, fully in charge of his faculties, now once again without Cleo directly present in his life. Having confronted reflections of himself as a drunkard and an old man, he seems here to register some need to address the present. At a press junket earlier in the film he was asked “Who Is Johnny Marco?” It’s as if, here, he might be starting to realize it’s a question worth considering.

At the end of the original 1937 version of A Star Is Born, Norman Maine, the down-on-his-luck alcoholic former star married to “It-Girl” Vicki Lester, having realized his wife will abandon her own stardom to care for him, walks slowly and deliberately to the Pacific to drown himself. The ending of Somewhere will resonate with any viewer familiar with that legendary film’s conclusion. Johnny checks out the Marmont, permanently, and drives. And drives. And drives. Coppola connects a half-dozen rear-perspective shots of him in his Ferrari driving out of Hollywood towards the desert, each of them taking him a few miles further from his now-former life.

Far away from the Marmont, from the industry, from his obligations, Johnny pulls over, leaves his key in the ignition, and walks away from his Ferrari. Coppola cuts from the rear-view perspective 180 degrees to Johnny walking toward the camera for the film’s final ten-second shot. Wherever Johnny Marco is going, in this scene that echoes A Star Is Born, it’s not towards the end of his life; it’s towards some kind of new beginning, some kind of spiritual rebirth, one without the Ferrari and the other trappings of fame. One that, one hopes, includes his daughter, Cleo, with more consistency. It’s clear his time with her has changed him; it’s just not clear yet, how. Just before Coppola cuts to black, Johnny creases his lips with the slightest of smiles.

Overall, Somewhere owes more of a debt to the existentialism of European cinema generally and the French New Wave more specifically than most of these lurid Star-Is-Born Hollywood tales of crime and vice. Critics have noted subtle allusions to Agnes Varda, Jean-Luc Godard, Federico Fellini. Perhaps those, coupled with the film’s languid pace and ambiguous ending, account for its mixed reception, something to which Coppola is no stranger. As daughter of a Hollywood icon—a world traveler, aspiring photographer, celebrity model, and a director who can shoot at locations betraying her privilege, among them not only the Chateau Marmont but the Park Hyatt Tokyo and Shibuya Crossing in Tokyo (Lost in Translation), the Palace of Versailles (in Marie Antoinette) or Paris Hilton’s house (in The Bling Ring), Coppola’s oeuvre tends to divide among those who see her films as trifles of the too-idle rich and those who value the cinematic lens through which she tells the stories of disaffected young women.

Somewhere is a different type of Hollywood-on-Hollywood film than most. Unlike Sunset Blvd, The Player, or In a Lonely Place, there’s no murder-mystery. Unlike Stand-In, Sullivan’s Travels, or Hail! Caesar, there’s no on-set or backstage shenanigans. Unlike Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? or Sunset Blvd, there’s no psychological horror or noir-tinged melodrama. In comparison to most films about film people, Somewhere avoids nearly every trope—or cliché—of the subgenre, instead employing its long takes, minimalist editing and cinematography, low-key storyline, and pared-down aesthetic to tell a simple, touching story of a young celebrity adrift at life and inept at fatherhood, but willing ultimately to sacrifice for change.