The best documentaries share many traits, among them an ability to generalize from the particular, sometimes in surprising, unexpected ways. Salesman (1969) became a treatise on the failure of religion and capitalism to realize the American Dream. Tarnation (2003), the potential of filmic montage to depict and understand psychological trauma. And the more recent Minding the Gap (2018) was less about skateboarding than the crisis of masculinity faced by a generation of Millennials. The Last Out, ostensibly “about” baseball in the same way the above films are “about” salesmanship, adolescence, and skateboarding, respectively, does something similar: along its messy, tortured trail it becomes a harrowing tale of migration and the commodification of talent.

Debuting on PBS in the U.S. as part of the long-running POV series, The Last Out is on its face a baseball tale. If your knowledge of Cuban-born baseball players reaching the big leagues is limited like mine to the Luis Tiants, Tony Olivas, and Rafael Palmeiros of yesteryear and a few of today’s bright stars like Raisel Iglesias, Yasmani Grandal, and José Abreu, you might know that there exists a pipeline of extraordinary talent from Cuba to the Major Leagues. There might be fewer players from Cuba than from the Dominican Republic or Venezuela, but given that Cubans must defect from their homeland, riddled by economic and political instability, and reach the U.S. only via another country, the impact of their accomplishment in the Major Leagues is not only impressive: it’s astonishing. In 2021, ten Cuban-born players reached the playoffs; in 2022, over 30 played during the season. But reaching the majors can require a perilous journey.

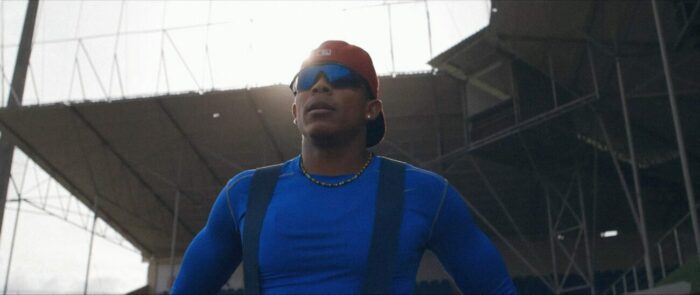

Even if you can name a handful of Cuban baseball players, you are less likely to know the names of the three subjects of The Last Out: Happy Oliveros, Carlos O. González, and Victor Baró. Each of the three risks exile to train in Central America as they chase their dreams of playing in the Major Leagues. Happy, like his nickname suggests, is a happy-go-lucky optimist, a buff athlete with footspeed on the basepaths and a live bat to boot. His unfailing optimism persists even in the face of some tepid performance in front of scouts and a series of dispiriting setbacks.

Carlos and Victor, meanwhile, are both pitchers, if of different temperaments. Scouts call the diminutive Carlos a “bulldog” for his smaller stature and fierce tenacity: he’s quiet, determined, and skilled, lighting up the radar guns and scouts’ smiles at tryouts. Victor may not have the same live arm—his pitches don’t pop the mitt the same way as Carlos’—but his array of breaking balls has its own keen potential, and he seems relaxed and confident throughout his journey. But it’s not easy for any of the three, and don’t bother scouting this October’s postseason rosters for the names Oliveros, González, or Baró.

Then again, The Last Out isn’t really about baseball at all. Baseball is simply the setting for a tale of migration. Directors Sami Khan (Oscar-nominated for St. Louis Superman) and Michael Gassert followed the trio for more than four years, using vérité techniques to focus on these young men and their families, each of them caught between countries, all of them hoping simply for a home for their talents and a life for themselves. The film’s cinematography (by Gassert and Jonathan Miller) veers from low-res, dimly-lit, before-sunrise wake-up calls and family meals in crowded home kitchens to evocative, aesthetic, unusual compositions conveying the game’s grime and grace.

The three prospects face numerous obstacles on their journey. Unlike their counterparts originating from, say, the Dominican Republic, a Cuban player cannot be contacted directly by a U.S. talent scout, due to the U.S. comprehensive economic embargo of the island. Each major league franchise monitors the performance of Cuban pro league players, but the only way for one of their players to be contacted is if he defects from his homeland. And as if that weren’t a significant enough consequence—having to abandon one’s home in the mere hopes of a potential tryout!—the whole process delays the Cuban player’s progress. Where a Dominican player might be first contacted at age 12 or 13 and signed by 16, a Cuban is rarely recruited before his late teens and will have to be signed in another country.

Talent agents have, for better and often worse, created a workaround, a pipeline for Cuban players to defect to another Central American country like Costa Rica. Once there, the prospect can be recruited by the scouts representing the big-league teams like the Houston Astros or Chicago White Sox, to name two who have successfully developed Cuban-born talent onto their playoff rosters. But the odds are stacked against the prospect, frankly, and language barriers further jeopardize their futures. Is a $300,000 verbal offer going to materialize? The player assumes so; we viewers are given to doubt. The agents, meanwhile, like the featured Gus Dominguez, who was once convicted of illegally assisting five Cuban players cross the border into the United States, have their own agenda—a cut of a deal—and when a deal doesn’t materialize, the prospect no longer has any value to them. Cut loose from any support, he’s left homeless in a foreign country.

Here is where The Last Out becomes less about baseball and more about the merciless, inhumane commodification of talent, especially that of Black and Brown people. Fans in the States might enjoy their nights at the ballpark, rooting for their “home” teams of players from across North and Central America and the world, wolfing down their ten-dollar dogs and beers, while the billionaire team owners fleece taxpayers for their new stadiums. Meanwhile, hoping, just hoping, for a chance to reach the bigs, somewhere there is a once-happy kid, having left his homeland, duped by an unscrupulous and uncaring agent, sold his gear, on a harrowing nighttime river crossing, just another “undocumented” immigrant with talent and aspirations whose dreams are on the cusp of turning into nightmare.

It’s a sobering watch, to be sure, but a great film, like so many other marvelous documentaries that become about something other than their topic, and the title “The Last Out” takes on more than its face-value meaning. Escaping Cuba is, for some, the last out imaginable, but the so-called American Dream of independence and prosperity is based on cheap labor sought in developing nations. For the young and vulnerable talented enough to chase the dream, they do so with a painful legacy of exploitation behind them and a potentially harrowing journey ahead.

This year’s MLB playoffs begin Oct. 7. Whether you’re a fan or not, The Last Out, debuting a few days beforehand, will provide an eloquent counternarrative to the success stories unfolding on the field. For the dozen or so Cuban-born players likely dotting the playoff rosters, there are equal or many more Happys, Carloses, and Victors whose likelihood of stardom is remote and journey to America perilous.

The Last Out premieres on PBS broadcast Monday, October 3, 2022 (check local listings), and will be available to stream free until November 2, 2022 at pbs.org and the PBS Video app. Both the English and Spanish language versions of The Last Out will debut as part of POV’s 35th anniversary season, coinciding with Hispanic Heritage Month and the start of the MLB postseason.