The “Create” segment of the London Film Festival is devoted to showcasing the creative process through features and documentaries exploring the lives and works of artists, writers, filmmakers and musicians. This year the program includes a pair of music documentaries on the roots of Techno and the story of the UK soul band Cymande, a naturalist document on the ecosystem of Sable Island, a biographical tribute to the Godfather of Avant-Garde cinema, and the surrealist Franco-Italian drama Leonora Addio.

Geographies of Solitude (dir. Jacquelyn Mills, Canada)

This is a wet autumn afternoon movie and luckily, I had a wet autumn afternoon to watch it on. Geographies of Solitude—which I seem pathologically incapable of typing without adding an “r” to today—uses experimental techniques of sound and film development to ingrain the viewer in the miniscule rhythms of life and death on Sable Island off the Eastern coast of Canada. Along with the film’s director, editor and cinematographer Jacqueline Mills, our guide to the island is its guardian of many decades and sole resident Zoe Lucas, a naturalist researcher who has been documenting and one might say, gardening, the island for over thirty years. Having arrived many years earlier to document the progress of the island’s horse population, Lucas has settled there and added combing the beach for plastics, collecting invertebrate samples, and otherwise sustaining and promoting the island’s health to her remit.

Lucas is accompanied in these endeavors by her documentarian Mills, whose appreciation for Lucas and her work inspires similar inquiries on her end, exploring different ways of creating sounds and images for the film that originate from the island. This results in a film wonderfully soundtracked by the footsteps of beetles and the ECG of snails and including impressionist montages created by exposing film to starlight and sea spray and developing it in fluid extracted from yarrow and seaweed. Otherwise, the whole film was shot on 16mm often using macro lenses to get some beautiful close ups of the local flora and fauna, and there’s as much here to delight aficionados of analogue filmmaking as lovers of the natural world. The sound design is equally impressive, with a tactile aesthetic that relishes the natural grittiness of Sable.

Under different circumstances Sable Island could look extremely forbidding and inhospitable, with its beaches often buffeted by north Atlantic winds that disturb the ever-shifting sands. But the deeper you look, the more beauty there is to be found, and Geographies of Solitude encourages you to look very deeply indeed. Lucas’s task of documenting and maintaining the island never ends, and the longer the film goes on the more Sisyphean her task appears, as she tries to limit the impacts of plastic pollution on her island’s inhabitants. The film’s environmentalist themes speak for themselves, with the film more preoccupied with a love for and wonder at the natural world, from the cuddly grey seals that loll on Sable’s beaches to the microbes that facilitate the islands many natural cycles of death, growth and rebirth.

The film often feels like a collaboration between the two women, each inspiring the another with their companionship and curiosity, but despite the title, it has few aspirations of being a human-interest drama, which perhaps makes the few moments of personal vulnerability all the more touching, as when Lucas admits to losing touch with the world beyond her coastline, or Mills asks her to stick around while she makes field recordings, sorry to lose her companionship. This does mean the film is a slow, ruminative experience and doesn’t ever seem to be fighting for your attention, but as any naturalist will tell you, there’s always something there that will absorb you if you let it and Geographies of Solitude is testament to that.

Fragments of Paradise (dir. KD Davison, USA)

Fragments of Paradise contains original film footage with imagery and sustained flashing lights that may affect those susceptible to photosensitive epilepsy or other photosensitivities. Viewer discretion is advised.

When reviewing any documentary where it is readily conceivable that the target viewer will have some foreknowledge of its subject, it’s a matter of journalistic integrity to admit when one does not. I had heard of Jonas Mekas. When I looked him up prior to viewing this film, I came upon his film As I Was Moving Ahead Occasionally I Saw Brief Glimpses of Beauty and thought, “oh yeah, I’ve heard of that”. That’s a precise measure of my awareness of his work. I’ve seen none of it, nor many other products of the artistic movement he was instrumental in. Underground and avant-garde cinema isn’t really my thing, it being a product of an era when “counter-culture” actually meant something, while I am not, perhaps sadly.

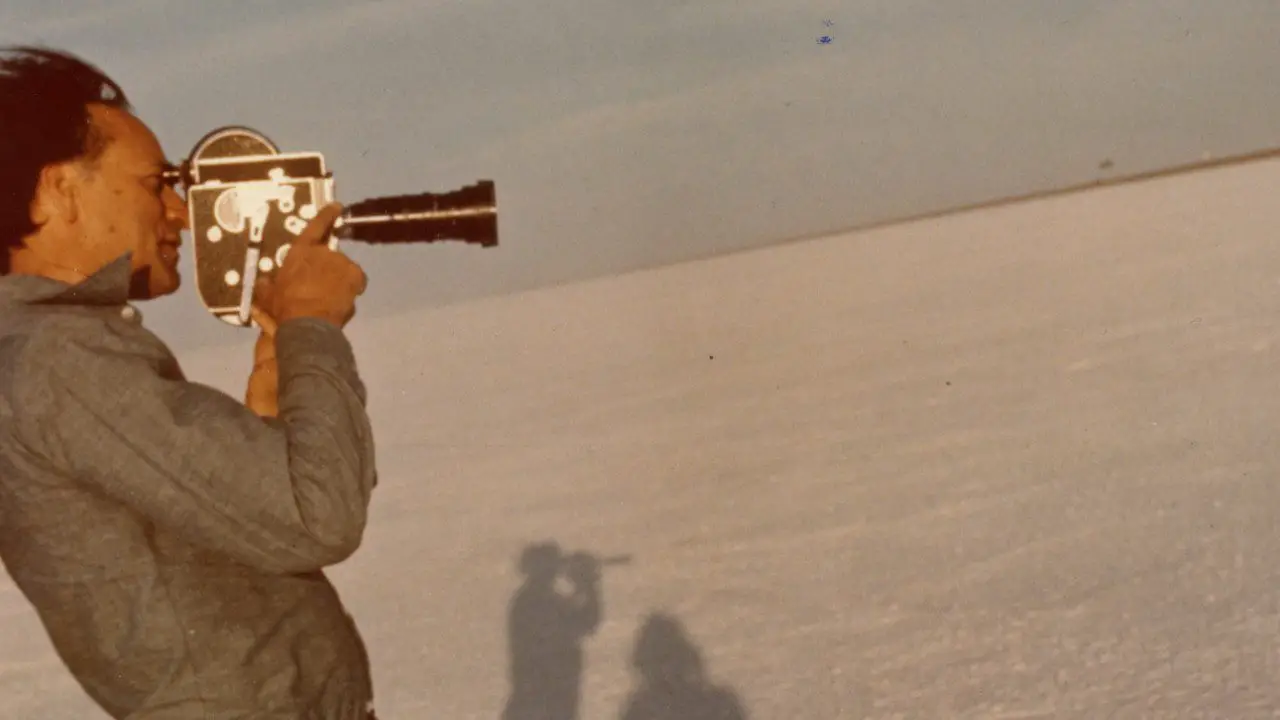

Mekas was a born filmmaker, as this film wastes no time establishing. He was rarely without his camera at his side and he shot many hours of diaristic footage, some of which he assembled into the aforementioned opus, some was until not unseen. Fragments of Paradise is a biography constructed out of this footage, along with various interviews with his friends and family, as well as the luminaries he and his work inspired, including among their ranks some very illustrious names like John Waters, Martin Scorsese and Jim Jarmusch, all of whom are full of praise, though no one seems to have been quite able to reach a consensus on how to pronounce Mekas’s name.

Mekas’s life was evidently a rich and full one, albeit one touched by pain. It was once he came to America that the Lithuanian poet traded his pen for a camera. His first artistic flourishing was forged in a German labor camp, his second in the streets of New York where he and his brother lived as exiles, persona non grata to the new Soviet regime at home and unable to return to their family. That his lifelong love of film emerged from such a painful injustice, it’s no surprise that he should find himself more drawn to underground and countercultural films, with the institutions of Hollywood holding less appeal than the micro-budgeted abstractions of Brookyln bohemia, among the Andy Warhols and Allen Ginsbergs of which, Mekas found a home. In turn, he resolved to give them a home, and started setting up journals, archives and co-operatives to support, restore, distribute and exhibit the work of America’s avant-garde filmmakers, many of whom he helped find audience.

The film is broken up into four chapters dealing with different eras and aspects of his life. The first his work with Film Journal and other aforementioned projects, the second, his experience of exile from his homeland, third, his long marriage and fatherhood, and lastly his final years of acclaim. Each segment is fascinating in its own way, he no doubt lead an extraordinary life, but that’s not to say he harbored no regrets into his old age. Clearly he did, even if neither he nor the film calls them by their name.

The film acknowledges his early homophobic pieces in Film Journal, but emphasizes his change of heart and subsequent support and defense of queer artistry. The film does not however mention the debates concerning his alleged pro-Nazi activities prior to his departure from Lithuania. Could a film about Mekas have put these matters to rest while preserving its primary role of celebrating his life and achievements? I think so, and it’s a shame the filmmakers didn’t do more to either defend Mekas or explore him in a more nuanced manner. It seems keen to see him as his films present him: jovial, sensitive, full of life and spirit, and deeply intoxicated by the medium of film. To see him thus, perhaps his own films present a better opportunity?

Fragments of Paradise does provide some desperately moving moments of vulnerability, principally the one that bookends the film, revealing Mekas at his lowest. There’s something almost intrusive about this material. It’s so extreme and disharmonious with the image the rest of the film paints of him, you almost question the appropriateness of including it. But then again, Mekas put his whole life on film, including this near-total emotional breakdown, why should this be excluded? Either way, it feels like another unanswered question hovering over the film’s subject. Fragments of Paradise would hardly be the first documentary to go out of its way to place a halo on its subject, but I think a yet more interesting and moving documentary was left unmade.

As a result, I’m unsure as to how fans of Mekas will respond to this film. No doubt many will adore it as a passionate and respectful testament to his life and his zeal. Others might find it incurious and yearn for something more revealing. Or perhaps his own work provides context I’m lacking, I shall stand corrected if so. From my own perspective, I loved watching this film, it offered me a charming window into a world and a man I had little knowledge of, his admirable work and inspiring commitment to it, and a poignant human-interest story of a son, a husband and a father, and the impact his presence or absence left on those around him. It was only afterwards I began to wonder “is that it?” Ninety-eight minutes is a brief span of time to devote to a man whose own autobiographical works frequently ran in excess of three hours, perhaps it would’ve felt redundant to say more, and I was robbed of the potential emotional impact of what is there. Seeing family members familiar from so many hours of footage break down in tears in memory of the father who shot it might well open floodgates for Mekas’s more devoted admirers, of which I’m sure he had many, and among which I should perhaps like to count myself one day.

Leonora Addio (dir. Paolo Taviani, Italy)

Another persona of whom I had previously lived in ignorance of was Italian novelist and playwright Luigi Pirandello, the subject of this film. Pirandello is not the main character though, as although this film is historical fiction (and not documentary as it has been erroneously described) it begins with his triumph at the 1934 Nobel Prize ceremony and immediately proceeds to his death shortly thereafter. The film that follows employs a broken-backed, almost anthological structure, with the first hour following a Delegate from his Sicilian hometown (Fabrizio Ferracane) summoned to bring his remains home, a process delayed by many years of conflict. The last third takes a different route, adapting The Nail, Pirandello’s last published work, itself a piece of historical fiction dramatizing the events surrounding a shocking and inexplicable act of violence that took place one day in Brooklyn.

Pirandello’s will stipulated a pauper’s funeral, a baffling request to the fascist authorities who had little grasp of humility and felt a man of such renown and national pride must be interred accordingly. The will did however propose an alternative, that his ashes be interred in the earth of his home town, and after the war, efforts are made to see his second choice put into action, a mildly absurdist process. The satirical portrait this second act paints of post-war Italy is a compelling, gently amusing and often rather poignant one, with the picaresque journey from Rome to rural Sicily providing an excellent throughline to explore the state of the nation, overrun with conquering American soldiers, some Italians trying to resume their former lives like nothing has happened, others adjusting to wildly new circumstances.

I doubt it’s a common experience for those born and raised outside of the English-speaking world to see themselves depicted onscreen in an uncomfortable, stilted fashion by Anglophone films. It’s an experience native English speakers can feel some semblance of when watching a film like Leonora Addio, where by far the weakest aspect is the acting of the English-speaking cast. It happens often when a production of one nationality attempts to portray those of another, and a cast of one language are being directed by a crew of another, with results that feel immediately and uncannily wrong. This is an issue throughout the film whenever our protagonist comes upon an American soldier or suchlike, but it becomes a more sustained issue in the last third when the film decamps to Brooklyn and we get extended period of “American” dialogue, full of odd delivery and questionable accents.

This strange effect is likely to keep English speakers at a distance from Leonora Addio, as would the relative obscurity of its subject globally, and sometimes the low quality VFX (could they really not have found an actual working crematorium?). However, if you can forgive it that, as well as its unusual approach to structure—effectively expanding its short runtime by adding a different short film onto the end—then the first hour of Leonora Addio presents a poignant, tragic often beautiful and subtly comic experience, ruminating on the character of life, death and personal and national dignity, held together well by the measured pacing, beautiful black and white cinematography and the world-weary presence of Ferracane’s long-suffering bureaucrat. The short episodes alternate sincerity with absurdism in a very humane way, and I loved the short little non-sequitur where a middle-aged priest discusses Pirandello’s work with a new generation of novices in a very warm, understanding and affectionate way.

The last third is likely what will divide people. It is a strange choice, but one can see the logic of folding an adaptation of the writer’s work into a film about his death and seeing the last thing he wrote before dying might have offered some insight into his mindset in the final days. However, the story of the moral alienation experienced by an emigrant boy in New York doesn’t do much (if anything to be brutal) to reinforce the film that came before. It’s basically a shorter, less developed version Camus’s The Outsider starring a child. It’s an imperfect end to the film but I think a forgivable curiosity. Since watching (and loving) Parallel Mothers, I’ve learned to be a lot more accepting of films that don’t all pull in the same direction. Why not have films that do multiple different things or explore different ideas in their turn? However, I do think it’s fair to argue that the dual explorations of the artist’s death and of his work that are presented here, could’ve been dovetailed in a more creative and rewarding way. It’s enjoyable, engaging, but doesn’t sustain the wistful satirical temperature that’s its strongest asset.

God Said Give ‘Em Drum Machines (dir. Kristian R. Hill, USA)

It’s hard to think of a single popular Western musical genre that black people were not at the cutting edge of from the outset. It’s kind of staggering how many of the defined artistic movements of the 20th Century originated in black music, and surprisingly often, it was the city of Detroit in particular that was the epicenter. When in the early ’80s synthesizers, samplers and drum machines became widely available, it led to a proliferation of different musical styles and movements, wherein burgeoning artists were freed from the limitations of classical training and industry support, able to make professional sounding (as opposed to punk) music at home with no more than the few hundred dollars such equipment cost. The film’s title originates in a joke told by one of its interview subjects: how did God respond when confronted with the violence and poverty endemic throughout black America?

Of course, hip-hop arose out of this same combination of elements, but so too did the dance scene incubate multiple different subgenres of Electronic Dance Music, House, Trance, and ultimately, from black Detroit, Techno: a combination of the Modern club DJ set and the House music arising from Chicago’s gay scene. The film takes as its springboard a single photograph taken in 1988 of six of the biggest creative heads in Detroit Techno, with each of the film’s interview subjects recalling their own journey to the genre, one another, the growth fostered in their collaborations and the development of the social movement that Techno became. These sequences are fun, exciting and showcase an infectious passion for the expressive, rebellious, avant-futurist music that has become synonymous with good times and late nights had worldwide. The subjects are charming and present a winningly personal and intimate version of their own approach to and journey through the world of music.

The arc of history that followed is a sadly predictable one, with the genre incubated in the gay clubs and black areas of the Midwest, until white artists began to take an interest in the exciting new sound, whereafter the black and queer pioneers were slowly left behind, in favor of white faces the industry found itself more comfortable with.

Sadly, like Fragments of Paradise, at the center of God Said Give ‘Em Drum Machines there’s controversy and division that the film seems unable or unwilling to draw its subject on. Ending text reveals that one of the film’s subjects was recently alleged to have committed sexual assault, though no charges have been filed, a strange inclusion as it is neither relevant to the subject under discussion nor something the film ever interrogates and makes relevant. More impactful though is the film’s failure to come up with any satisfying answers about what caused the rift between the men being interviewed. We hear of a fateful night when one of their number walked off stage, but he clearly doesn’t wish to elaborate on his feelings, nor do his former bandmates suggest anything but the vaguest of personality clashes and differing levels of charisma and success, despite there being such bad blood that two of them haven’t spoken to one another for decades (there’s footage of the two just meters apart at one live event). This was clearly never conceived as a biographical band documentary, but it’s hard not to feel frustrated by such a big unanswered question.

There’s a lot to be learned from God Said Give ‘Em Drum Machines, perhaps above all is the lesson that there’s more to the story of Techno’s origins than a single ninety-minute documentary could ever have contained, especially when it intends to maintain such a personal focus. Perhaps a broader approach could’ve helped, and as with almost all music documentaries, I’d have liked to have heard more about the music itself, how it was distinct from adjacent genres, and a clearer timeline of how the sound grew through the convergent evolution of different independent artists, influencing each other and being influenced in their turn. There’s still a lot of that here though and it’s the best part of the film. Sadly, though the creative and personal differences between the men in question do start to sour the experience, as they did the scene at the time.

The film almost accidentally implies that these pioneers had no one to blame but themselves for a white man having taken their sound. Being the figurehead of a sound is hard work. More than genius, it takes a lot of commitment and either a lot of privilege or a lot of compromise, and perhaps that’s something these guys weren’t able or willing to put in. The story of Techno’s birth is a fascinating journey with a heck of a lot of great music, and one any EDM fan should be eager to discover, but as presented by God Said Give ‘Em Drum Machines, it’s a confused and incomplete picture that sometimes leaves the viewer with more questions than it answered.

Getting It Back: The Story of Cymande (dir. Tim MacKenzie-Smith, UK)

After a string of documentaries the subjects of which I was ignorant, finally I get to show off my hipster credentials and talk about something I’ve known about and loved for years, the band Cymande. Like most of the sounds I loved for most of my teenage years, I discovered Cymande through the movies. I first heard the song “Bra” on the soundtrack to Spike Lee’s film The 25th Hour, I was instantly hooked by that iconic groove, and it’s been in rotation ever since. As I discovered through this film, I wasn’t alone in taking a sideways journey towards Cymande though, as for much of their careers, they existed as one of the greatest and most influential sleeper acts of the 20th Century.

Getting It Back follows the group from its inception, as a bunch of self-taught West Indian musicians got together in the clubs of London’s Brixton district and started playing together, through their brief taste of success overseas in the states, before finding themselves unable to get anything going at home in the UK, with TV and radio stations unresponsive to an all black group of jazz, funk, soul and reggae musicians. Unable to keep finding bookings, they disbanded after just a few years. But the movie’s called “Getting It Back” and their music lived, and went onto a second life, with the catalogue of impeccable grooves being a gift to the burgeoning scenes of sample-based hip-hop and house music. After thirty years of obscurity, Cymande slowly became the band to know again.

Their story is a strange mirror to the one told by our previous film, God Said Give ‘Em Drum Machines. Where the Detroit Techno artists of the ’80s found the London club scene responsive to their sound, the British musical establishment of a decade prior gave Cymande a very different kind of welcome, stifling their growth and breaking the band’s spirit to record. In a hilarious coincidence, both films wound up using the exact same stock footage of a child holding a can over a fire hydrant!

Getting It Back has everything one could ask of a great music doc, all in ninety minutes. Most band docs choose the personal stories and branding, and neglect the music itself, its impact on the culture and the way subcultures grew up around it. Getting It Back has moments as poignant as any comparable artist documentary – though significantly less of the usual drama with every member of Cymande coming across as the nicest guys you could hope to support – but it also feeds the musical perspective and fosters an affection and appreciation of the music itself like no other. Of course it helps no end that the music Cymande made was just exquisite, their self-titled record sounds perfect to this day and as a music listener born in 1996, it’s quite possibly my favorite ’70s album.

Perhaps I’m showing my bias then in calling Getting It Back my favorite film of the festival yet. I could gush over the band’s work and ethos and the impact they had as long as any of its interviewees—who unlike many such docs, seem to have been chosen for their genuine passion and knowledge rather than their clout—albeit with significantly less credibility, but it’s still an inspiring and deeply fond testament to the power of music and the joy of finding your self-belief justified. For fans of the band, it’s a pure delight, for newcomers, an urgent wake up to one of the greatest bands of the seventies. Whoever you are, seeing these guys finally get their flowers and play festivals in their seventies is unspeakably heartwarming.