Atom Egoyan’s The Sweet Hereafter, adapted from the novel by Russell Banks, begins with an opening credits sequence notable for its austerity and simplicity: a right-moving, horizontal tracking shot on a bland wooden floor that finally settles on the idyllic, peaceful sight of a man, a woman, and their young daughter in bed together in the early hours of the morning. All of them are perfectly still and asleep, the white sheets of the bed which cover their partially undressed figures offering the image an air of mythical idealism—an air that, as we learn from the man in the frame, Mitchell Stephens (Ian Holm), in a later scene, instantly deteriorated when Zoe, their daughter, reacted near-fatally to a possible bite from a baby black widow spider.

Mitchell describes this deterioration in harrowing detail many years after the fact, with Zoe (Caerthan Banks) now a fully-grown adult and a destitute drug addict. The person he’s telling this story to is Allison O’Donnell (Stephanie Morgenstern), a childhood friend of Zoe’s who he now happens to be sitting next to on a plane on November 29, 1997, and she watches with an air of morbid fascination as Mitchell unfolds in emotionally repressed yet unflinchingly honest fashion what happened that morning. Faced with the possibility of having to perform an emergency tracheotomy on Zoe if her throat closes because of the swelling, Mitchell vividly recalls the image of holding Zoe in his lap during the drive to the hospital, singing her a lullaby to soothe her, all while holding a barely-sterilized knife next to her head, anxiously waiting for the moment her throat shuts. It’s an unbearably tense and nerve-shredding image we also get to see from his point of view while he describes it, as the swollen-faced Zoe stares up into the camera, and unnervingly enough, right at us, with the knife about to cut into her throat if necessary left out of focus behind her.

As evidenced by the fact that we see Zoe as an adult, making phone calls to her now-despondent father and begging him for money, the tracheotomy never became necessary, and she survived just fine. But at the same time, it’s with the realization of what she became that one particular line in Mitchell’s recollection of this experience stands out: “Zoe loved us equally then… just as she hates us both equally now.” It’s a telling confession of unbearable parental guilt set within the framework of a deeply disturbing incident… and it doesn’t help that the scene directly preceding Mitchell’s confession is that of a school bus full of children losing control on a slippery winter road, careening off the hillside, and sinking slowly under the ice on a lake, the camera observing all this from a faraway distance.

Twenty-five years after The Sweet Hereafter’s theatrical release in 1997, Atom Egoyan’s tale of collective grief, guilt, and lost innocence still remains as emotionally brutalizing and intensely solemn as ever, reaching a handful of searing truths about all of these themes that astonishingly few dramatic films of its ilk have even come close to grasping. Tracing his way through the aftermath of a horrific school bus accident that killed 14 children in the small Canadian town of Sam Dent, British Columbia, Mitchell meets with the bereaved parents in order to persuade them to join a class-action lawsuit against the town and bus company for negligence in the bus’s construction. In the process of doing so, he not only faces each of the parents’ conflicting interests and emotions, but also those of the accident’s survivors—namely, Dolores Driscoll (Gabrielle Rose), the bus driver, and Nicole Burnell (Sarah Polley), a 15-year-old survivor of the accident who’s been paralyzed from the waist down.

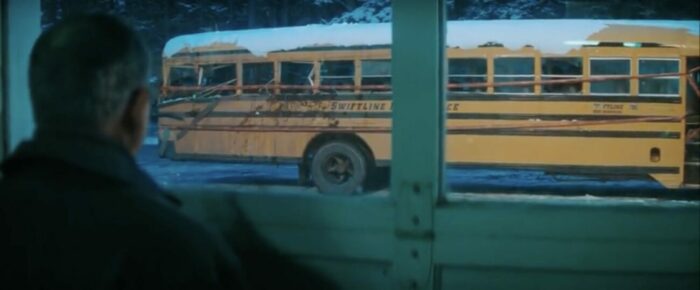

The Sweet Hereafter navigates its way through several distinct narrative threads: the events leading up to the accident, the day of the accident, Mitchell’s discussions with the parents and survivors in its aftermath, and the plane ride he’s on with Allison several years later. Finding each of these threads’ chronological place in the story is a process that Egoyan and editor Susan Shipton treat with great care to pacing and attention to revealing details—the first glimpse of the bus we get is after Mitchell gets out of a stuck car wash, trying to find someone who can help him, before gazing out of the shop owner’s garage window to find it busted up and dented all over, held together with rope and glazed over with snow, all while the faint, terrible sound of children screaming fades in. Any allusions to the accident in the first half are in Mitchell’s discussions; first with the Walker family, then with Dolores, and finally with the Otto family. In between, we’re given glimpses at Nicole and the life she led before the accident, as a burgeoning young singer under the control of her father, Sam (Tom McCamus), herself being deeply acquainted with some of the children who would end up dying in the accident.

This control of information is perfectly complemented by Egoyan’s expert control of emotion as well, with each of the families and survivors that Egoyan interviews having their own way of coping with the crushing grief and guilt they experience. The Walkers, for one, exhibit a response marked by a bitter sense of repression, one that leaks into how the father, Wendell (Maury Chaykin), tears apart the character flaws of the many victim families that his wife, Risa (Alberta Watson), numbingly suggests to Mitchell as more possible contributors to the lawsuit. (The scene also works as an excellent primer to a fundamental facet of the film’s small-town conceit—everyone knows everyone here. Mitchell not only has to contend with being the person to reopen these parents’ fresh wounds out a bid to earn them legal closure, but also has to live with the fact that he’s an urban outsider who doesn’t belong in this rural area, trying to fight a tragedy that’s hit an entire chain of families whose relationships to each other have been irrevocably changed.) On the near-opposite side of that are the Ottos, widely reputed in the community for being hippie-types, who’ve been so consumed by sadness and anger that their already shaky attempt at repression subtly yet heartbreakingly crumbles by the time Mitchell makes his empathy for their suffering clear.

Failing to mention The Sweet Hereafter’s performances at this point would be absurdly remiss. With the late, legendary, and sorely missed Ian Holm at the center bringing the best performance of his career by anchoring the emotional and moral center of this film in Mitchell’s guilt, the entire supporting cast surrounding him can’t help but be excellent at conveying the gamut of emotions tied to these families’ heartbreak, without reducing said emotions to exaggerated absolutes. In particular, it’s Gabrielle Rose as Dolores who brings the most devastating perspective here — the bus driver working through how responsible she is about the accident, and who vividly remembers even the smallest details about the children she drove whose lives were lost. But she doesn’t make her emotional state immediately obvious; it takes some questions from Mitchell about the details of her driving and the circumstances surrounding it, all of which she answers with straightforward detail, for her to reach a sort of breaking point. Once she does, however, it’s brutal to witness just how heavily this accident has been weighing on her, an effect only amplified tenfold by how the camera subtly draws attention to a gallery of the children’s photos hung up on the wall directly behind her—a sign of the genuine care she had for them that’s now become a perpetual reminder of the guilt she’ll likely carry for the rest of her life.

As the film’s structure gets split down the middle by the accident itself—which Egoyan and cinematographer Paul Sarossy choose to film from a distance, a masterfully restrained gesture that only further drives home the horror of what actually happened—the story’s focus then shifts to Billy Ansel (Bruce Greenwood), the town’s regional automotive shop and car wash owner, and finally to Nicole, whose shattered sense of innocence and deeply disturbed family life makes her the most important yet unpredictable player in Mitchell’s lawsuit.

For Billy, his pain comes from him having been the accident’s sole witness. Having watched his two children die in front of him, his guilt overlaps with a newly placed certainty about what he saw that day—guilt that leads to a repressed, outwardly cold stoicism, as he callously rejects Mitchell’s class-action lawsuit and the other families’ willingness to go along with it. As for Nicole, she carries an immensely dark secret that drives her to take some form of agency against her situation, directly tying into the outcome of the lawsuit and her central role within it. Sarah Polley, now having made a name for herself as a renowned writer-director, strikingly portrays the enigma behind Nicole’s silently impenetrable personality, offering glimpses into her complex and traumatized interiority, but never fully revealing her character’s hand or the emotion behind her intentions. She only hints at it with voice-overs of Nicole reading the tale of the Pied Piper, in particular the lame child who could not catch up with the doomed children—a stanza frequently juxtaposed with what we see of Nicole after the accident.

If the first half of The Sweet Hereafter was about the ways these families and survivors grasped for any sort of closure through Mitchell’s lawsuit, the second half is about how Billy and Nicole, in their own ways, pierce straight through that desperation and have the audience gaze into an abyss of grey areas, looming feelings of futility, and no real conclusions. There’s an eerie sense of realism in how little The Sweet Hereafter is ultimately concerned with the outcome of Mitchell’s lawsuit, because its conclusion appears bygone from the beginning — the negligence that he wants to prove is likely a stretch to begin with, and Dolores happening to have lost control in the moment is likely more plausible than he wants the parents to believe. Mitchell himself is so evidently unconcerned about the money that you can instantly read his real motivation in his expression whenever he extends his sympathy to the parents: he’s not just doing this out of benevolence, but also out of personal atonement for how Zoe’s ended up.

This is not a lawsuit meant to be triumphantly won in court so that all wounds can finally be healed, and it’s not what offers the film any of its emotional potency. Rather, it’s in how the film instead depicts the permanence of the collective grief affecting this community that offers the story its immediacy, and in turn, its lasting relevance.

Tonally, The Sweet Hereafter‘s remarkable impact lies in how little it sensationalizes the bus crash, and how committed it is to refusing the emetic sentimentalism of countless other dramas also released in 1997. In a year where among the most popular movies being released were Good Will Hunting, Titanic, and Life Is Beautiful, every instance where Egoyan subtly and poetically translates the experience of collective grief stands out as being incredibly authentic in its bizarrely, deeply felt sensitivity. The way this film so completely eschews the histrionics and catharsis of its contemporaries is most likely what offers it such an intense degree of staying power. Unwilling to submit to the conventions of melodrama in service of its carefully told narrative, Egoyan’s film gives off the impression of a deeply empathetic film masquerading as a cold one, with a profoundly grounded melancholy and sadness exuding itself from its seemingly more detached exterior while never making them dramatically apparent.

It’s the right approach to take, because no tragedy like the one at The Sweet Hereafter‘s center ever leaves behind an easy answer. Egoyan, in particular, knows this—the film itself is also based on an actual bus crash in September of 1989, where 21 high school seniors and juniors in Alton, Texas drowned after a bottling truck crashed into the bus, leading it to swerve into a caliche pit of water. Every single death in an accident like this is senseless beyond belief, with so many people taken from us unfathomably sooner than necessary. The parents and loved ones of the dead are left behind to pick up the pieces and grasp at whatever memories are left behind, every memory a reminder of the guilt they carry for not having done something differently. All the while, everyone is left to try and find something to blame or reason with, just so that it gives any sort of closure that comes with not wanting to deal with the pain and grief forever. With death like this, everything changes—the air we breathe, the meals we eat, the work we do, the way we see each other—and nothing ever quite goes back to normal.

It’s no stretch to say that we’re currently living in a time when tragedy is impressing its impact on us more painfully than usual, not just with COVID ravaging our world and leaving millions dead in its wake, but also with accidents and disasters of various origins robbing countless families of their loved ones far too soon. Speaking as a Korean-American viewer, it’s recently been difficult not to think of the recent Halloween crowd crush in Seoul’s Itaewon district, where more than 150 people, many of whom were in their 20s, died in a brutal stampede down a narrow alleyway. The incident’s left the entire country shell-shocked and grieving as a result, with contradictory emotions and reactions spilling out from all corners, in a harrowingly similar way to this film’s methodical exploration of such complex emotions. There are real truths about the atmosphere, self-contradiction, and lingering melancholy behind this specific breed of grief—grief without a culprit, without a scapegoat, without an answer—that this genuinely evergreen film speaks to, and the pain of an accident like this is universal and constant no matter what societal context it takes place in.

It may simply be that 25 years after The Sweet Hereafter‘s release, we as a society have grown more conscious of how tragedy works, but none of that ultimately reduces the sheer pain of how tragedy feels. It’s a pain that’s so deeply tied to the human condition as a whole, and it’s one that Egoyan’s film understands with a sincere sense of compassion that’s nearly impossible to find anywhere else.

Nice Article

Tks excellent review of a great film.