However you choose to interpret The Haunting of Hill House—supernatural, psychological, or somewhere in between—one thing is certain: there is something terribly wrong with Olivia Crain. Ghost stories aside, Olivia’s descent into madness and the ripple effect that has on her husband and children are the heart of the series. At 25YL we have previously focused on each of the Crain siblings, but to me, Hugh and Olivia’s relationship is even more fascinating (and heartbreaking) because it gives the viewer a horrifying glimpse into what a marriage looks like when it’s haunted by the ghost of mental illness.

I am hesitant to define exactly what it is that Olivia suffers from as we are not given a definitive answer on this question during the series nor any concrete backstory that would help make that determination. What I do know is that Steve Crain’s armchair diagnosis (some amalgamation of schizophrenia, depression, mania, and dissociative disorder) isn’t correct. Steve probably did a very basic search on what symptoms he remembered and decided that, since his mother didn’t fall within one category, she must just have everything all at once. Of course, that is not even remotely how mental illness works, but it’s very Steve to assume that it does. He needs everything to have a clear-cut answer and solution—in his mind, she needed medication and treatment, and because she didn’t get it (and Hugh didn’t help her get it) she died, and it’s all his fault.

Hugh Crain the Younger sits on the opposite end of the spectrum with his insistence that Olivia is just overtired and stressed about the flip. Deep down he knows that this is not the case—that the Hill House experience is very different from previous houses—but his constant need to fix everything (his fatal flaw) requires that Olivia’s problems be something that he can solve. In Hugh’s worldview, all problems have a solution, if one just works at them hard enough. But again, mental illness does not work this way. There’s no fixing it; it’s always there. It is a ghost that cannot be exorcised because it is a part of your physical being. It lives in your chemistry and, though it can be managed, it is always and forever a part of you. For Mr. Fix-It Hugh, this is an impossible situation, and one he chooses to ignore until it’s too late.

What we do know about Olivia is that she suffers from chronic migraines: a physical condition that can be treated but which often cannot be fully eradicated. Migraines are similar to some mental illnesses in that they are caused by certain chemical imbalances in the brain. Olivia’s experience of terrible pain along with her light and sound sensitivity are common in migraine sufferers, and she has had them for years, so I think it’s safe to conclude that her migraines are just that—migraines—and unrelated to any other issues she may have.

To me, one of the most significant pieces of evidence that pre-Hill House Olivia had some form of mental illness in addition to her migraines is the way that she describes her experience of feeling many emotions, all at once. After the incident where she smashed the vanity mirror in front of young Steve, Olivia and Hugh have a conversation about her current mental state:

Hugh: “What am I supposed to do here? What do you want me to do, huh?”

Olivia: “I don’t know. I don’t know…I think I do need help. I think I need your help. Or someone’s. I don’t…I’m not me right now. I just…I can’t seem to find me.”

Hugh: “You’re tired. You’re stressed about the flip, about the kids, you…you’re stressed.”

Olivia: “No. I’m not. I was when we got here. I was all the things, all the familiar things. I was stressed and excited and content and motivated and concerned and exhausted and annoyed and grounded and nervous and creative and proud and…and all of the things. But all those colors, they’re all gone now, Hugh. And there’s only one left. I’m scared. That’s all I am. There’s nothing else. I’m only scared. Do you think there’s something wrong with me. Like…like…like, really wrong?”

Hugh: “I think Monday’s a little late for your trip.”

– The Haunting of Hill House, “Screaming Meemies” (S1E9)

When Olivia describes “all the familiar things,” it is evidence that Hill House was not the first time she’s been overwhelmed by emotions. She describes her emotions as colors, and while this could be a form of synesthesia, there is no other evidence to suggest that Olivia is a synesthetic. To me, her description of seeing “all those colors” is just a way that she can communicate her internal life to Hugh—to give language to her individual experience. It is nearly impossible for a person suffering mental illness to convey the way they experience the world to a neurotypical individual. To combat this, Olivia creates a language that Hugh can use to understand and communicate with her, but while he can understand that she is having one of her “color storms,” he really cannot conceive of what that feels like for her.

While being overwhelmed by conflicting emotional states is not something strictly limited to those with mental disorders, it is the way that Olivia communicates and describes her experience to Hugh that leads me to believe it is more than just your garden variety emotional overload. Of course, her presence in Hill House is exacerbating “all the familiar things,” but this is not an isolated incident. She is prone to emotional overload and, although there is no specific evidence in the series (and I’m entering Steve Crain armchair diagnostic territory), I would be willing to put money on the fact that at the very least Olivia lives with anxiety disorder.

What is clear is that Olivia is not well, and my reading of the root cause of her mental state falls somewhere between the purely supernatural and the purely psychological. The Haunting of Hill House can certainly be read either as a straightforward ghost story or as a metaphor for the horrors associated with mental illness, but I think a more fascinating interpretation is one that falls right down the middle. The ghosts of Hill House are real but “those who walk there, walk alone,” haunted by their own personal phantoms. In this reading of Hill House, Olivia is haunted by her illness but is able to manage it and live a full life until she arrives at Hill House, which begins to infect her and feed on her until she is so desperate to “wake up” from her living nightmare that she chooses the nuclear option.

I say “choose” here, but it isn’t really a choice because she is not even remotely in her right mind when she lets herself drop from the top of the spiral staircase. She has the ghost of Poppy Hill in her head, twisting and turning her around and convincing her to do the most horrible things in the name of keeping her family safe. If Hill House is like a body, Poppy is that part of the mind that lies to us. Everyone experiences this to some extent, but those suffering from mental illness experience it in a different way; it can become impossible to separate those sort of intrusive thoughts from reality, and this is what happens to Olivia. Hill House (via Poppy) infects her mind with lies in order to keep her there and feed on her forever (and feed her children to it as well). But Poppy’s lies are not far from the very real fears that Olivia might have as a mother, even without Poppy’s influence. At the core of it all is the fear that she cannot protect her children from the world as they grow older, and this is a completely legitimate worry. What shifts it from the logical to the illogical is the way that Hill House (via Poppy) makes her feel that it is the only safe place in the world when it is the exact opposite.

Hugh the Younger is not as susceptible to the creeping horrors of Hill House—at least initially—because he believes in a world that is black and white. In Hugh’s world, ghosts aren’t real (and this applies to both the supernatural form and the psychological form). That’s not to say that he doesn’t think that mental illness is real, but more that he fundamentally does not understand it. What he does grasp of it he believes can be fixed if you just work at it hard enough, which is an absolute death sentence for a marriage between a neurotypical partner and a mentally ill partner.

Which brings us to the kite and the line. In “Witness Marks” (S1E8), Hugh the Elder explains his marriage dynamic to adult Steve, who is having marital problems of his own:

Hugh: “She used to say she was the kite and I was the line. She was a creature of the clouds and I was a creature of the earth. And she’d say that without me she’d become untethered and she would float away…And then without her, I would just, you know, crash, just drop right down to the ground…You know, we still fought sometimes [after the brief separation], but it was different. We fought with love. She taught me that. You fight with love…You’re on the same team even in the middle of a fight. During the fight, you’re…you’re forgiven. There’s no fear. There’s no danger. You’re safe…It’s a beautiful way to be. You know, we weren’t perfect, but we were always kind. And we loved each other hard. And I love her today just as much as I did in the beginning. The kite and the line.”

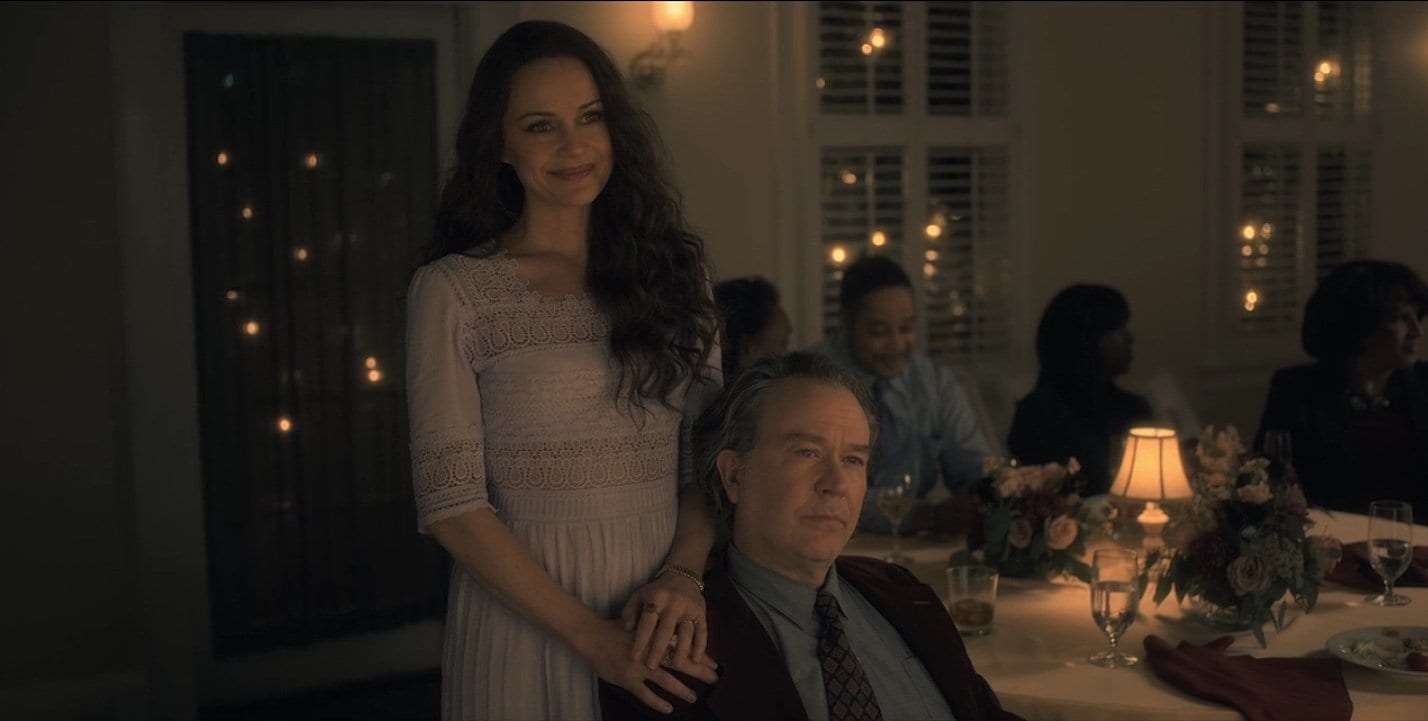

For a woman like Olivia, Hugh must have seemed like a godsend—he keeps her grounded, he can fix everything, they are partners who fight with love and love each other hard. She is the kite floating around with her head in the clouds, and he the line, keeping her tethered so she doesn’t float away and disappear into her own head. This dynamic may seem romantic and appealing, but it is not a foundation on which to build a successful marriage between a person who suffers from mental illness and a person who does not. That’s not to say that a mentally ill person does not need a partner who is there to support them and help them when they need it, but the entire concept of “the kite and the line”—that the neurotypical partner is the one thing holding the mentally ill partner together—is bad for both parties. It puts too much pressure on the line and takes some sense of personal responsibility and agency away from the kite.

In order for the kite/line dynamic to function, the line must be strong. It must be built up not just with hard love and mutual respect but with communication and an understanding of the hardest of all truths: you cannot “fix” someone with mental illness. A line is made from string and not steel; it’s vulnerable to the sharp edges of the world, and Hill House has teeth. Hugh and Olivia both fail to communicate with one another in a productive way: she isn’t honest with him (or herself) about what is going on with her and he isn’t receptive to hearing it. The closest they come to a healthy and productive conversation about her mental state is his suggestion that she take a break from Hill House and her agreement to do so. But because the line is not strong enough, it breaks once she leaves. She has been so totally dependent on it for so long that, once severed, she is left rudderless and floating. She can’t get on a plane to visit her sister; she barely leaves the area before she comes straight back to Hill House. But with the line now severed, her return to the house leaves her totally vulnerable to it, and that is the night where it all falls apart.

The fundamental flaw in Hugh and Olivia’s marriage is that he truly believes that he can “fix” her, and she allows him to believe this up until the very end. It is only once Hugh the Younger gets inside the Red Room and truly sees what has become of Olivia’s mind that he starts to understand not only what Hill House is capable of but what mental illness is capable of. He is forced to acknowledge that he cannot “fix” Olivia and all he can do at this point is try to keep his children safe. But he fails even at this because he still thinks he can fix everything for them via his usual modus operandi: refusing to acknowledge and/or concealing the truth. Instead of confronting what happened and telling the truth (or some age-appropriate version of it) to his kids, he leaves them with their Aunt Janet believing that is the best course of action—that shielding them from the reality of Hill House and what happened to Olivia is the only way that they will be able to live relatively normal lives. Of course, this is the worst possible way to handle it, which he comes to realize later in life, but at the time he himself is so broken by Olivia’s death and the horrible knowledge he received that final night at Hill House than he cannot be a line for anyone; he himself is far too broken to be able to fix anyone else.

Hugh the Elder carries Olivia’s ghost with him throughout his life but he knows that it is not real, that she’s just a figment of his imagination he uses as a coping mechanism (especially when he’s trying to reconnect with his children after Nell’s death). The older he gets and the more time he has to sit with the truth of what happened, the more he begins to understand the reality of the situation, both in terms of the power of Hill House and the power of the human mind. Hugh the Elder understands, via his own trauma and coping mechanisms, what the human mind is capable of—he can see Olivia, he can talk to her and receive guidance—but he is able to distinguish what exists in his mind from what exists in the world. Because he understands this, he finally has an understanding of what it would be like not to be able to distinguish the two, though this comes far too late. The line is broken and the kite is long gone, and the only way for Hugh to “fix” things for his remaining children is to embrace the madness of Hill House and become its last meal.

Glad I found this article. Love everything you wrote- was searching for the kite and the line quote and found much, much more! Thank you.