Star Trek is famously based on Gene Roddenberry’s hopeful vision of the future, in which humanity has largely moved on from its prejudices, penchant for violence, and other problems. Humans, Vulcans, and other alien species have joined together to form the Federation, a utopian, multi-planetary society. Starfleet, the Federation’s powerful diplomatic, peacekeeping, and space-exploring organization, has officers throughout the Alpha Quadrant upholding its idealistic principles. However, contrasting with the franchise’s other installments, Voyager gave the optimistic concept a new lease of life when it asked: how do you maintain that hopeful Starfleet integrity in the face of a hopeless situation?

In my opinion, Voyager is the best and most compelling entry in the Star Trek franchise, largely because it’s rooted in much darker themes, and in frankly depressing circumstances. That’s not to say it’s a depressing show. Optimism is still the main force that drives Voyager and its characters. But it’s one thing to be optimistic when you’re a successful Starfleet officer, backed by an inter-planetary organization, living as a member of a just and influential society, like most Star Trek characters. It’s quite another to retain that optimism when you’re lost in the Delta Quadrant, completely cut off from your family and friends, alone except for your small crew, 70,000 light-years from home—the situation that Voyager’s characters find themselves in.

Voyager’s darker premise allows it to combine more relatable storylines with the inspirational quality of classic Star Trek. Viewers struggling with their own problems, or with those of the wider world, can see their circumstances mirrored here. They can see how the characters deal with their own dire situations yet manage to keep going. For some, this is more helpful and more meaningful than visions of an idyllic future—though seeing that in other Star Trek shows is certainly important too.

For Voyager’s crew, the key to maintaining hope and integrity includes resisting the temptation to compromise their principles for a way out of the Delta Quadrant. Throughout the series we meet characters who are so desperate that they take extreme measures to achieve their impossible goals, not caring who gets hurt in the process. A prime example of this is in the two-part episode “Year of Hell”. Annorax, a member of the Krenim species who has the technology to alter the timeline, constantly wipes other species from history—and occasionally brings them back—in a never-ending effort to restore the Krenim to their former glory. Annorax is never satisfied, because no matter how successful he is, he always fails to bring back his wife and family. He won’t rest until he does so, and he uses his grief over his personal loss to justify genocide after genocide.

In contrast, over the years, Captain Janeway and her crew give up several chances to get home when the consequences would be harmful to others. They refuse to be corrupted by their desperation to return to the Alpha Quadrant, and they will not put their own desires over the wellbeing of others. Janeway demonstrates this restraint in the two-part pilot, “Caretaker”, when she destroys a space station containing Voyager’s only way home, in order to protect the Ocampa from the Kazon—who would certainly use the space station’s technology against them.

In the excellent episode “Eye of the Needle”, the crew resist the temptation to transport themselves through a small wormhole back to the Alpha Quadrant, when they realize the wormhole would actually take them back in time 20 years, and that this could have catastrophic effects on the timeline. In “Non Sequitur”, reality is actually changed so that Harry Kim was never on Voyager, and he is instead living an idyllic life back in San Francisco. Harry could take the easy way out and simply accept this new reality, but it doesn’t feel right, especially when he discovers that a friend of his is stuck on Voyager in his place, and that Tom Paris is significantly worse off in this timeline. Harry bites the bullet and changes reality back to how it was before, condemning himself to several more years in the Delta Quadrant.

Just as they don’t give in to the temptation to compromise their morals, the crew also resist giving in to depression—no matter how bad things get, they keep going. They don’t give up hope that life can get better. Even though they often have to give up on specific goals, such as using the wormhole in “Eye of the Needle” to return to the Alpha Quadrant, they maintain hope that they will find another way home. In the meantime, they find hope in each other and make the most of their time on Voyager.

A surprising number of episodes feature the crew working towards a goal, realizing they can’t fulfil it, having their hopes dashed multiple times, and ending up back where they started—or sometimes even worse off. Rather than representing weak or stagnant storytelling, these episodes are actually wonderful vignettes on how to deal with disappointment, depression, and hopelessness, and how to keep going in spite of it. In “Eye of the Needle”, for instance, the crew try to mitigate their disappointment that they can’t transport themselves to the Alpha Quadrant by hoping for smaller and smaller boons, but one by one these are all denied too.

First, the Romulan they are communicating with through the wormhole suggests that he could stop Starfleet from sending Voyager on the mission that led them to the Delta Quadrant, but even this would mess with the timeline too much. The crew then settles for giving the Romulan messages for their family and friends that he will pass on in 20 years, after Voyager has become lost in the Delta Quadrant. However, after the Romulan leaves, Tuvok looks him up and discovers that he died four years before Voyager set out, and before he would have delivered their messages.

The crew is crushed to learn that after all the hopes they pinned on the wormhole, even this basic request was not to be. Janeway allows herself a moment to feel the pain, then shakes it off and returns to business as usual, encouraging the crew to do the same. This goal didn’t work out, but they can’t afford to dwell on it. They must simply accept it and move on, refocusing their energy on their mission to try to get home the long way, and to explore the Delta Quadrant as they go.

One of the most devastating yet brilliant episodes, “Course: Oblivion”, follows this pattern to a much more extreme conclusion. It’s almost shocking that the writers and networks actually made such a depressing episode of a ‘90s primetime show, especially one that’s part of a franchise known for its optimism. “Course: Oblivion” starts off happily, with Tom Paris and B’Elanna Torres getting married, and Voyager not far from home due to some new technology they’ve picked up. Soon, characters begin to fall ill, including B’Elanna. After a while, B’Elanna—a main character—dies. In most shows you would assume that this will all be reversed by the episode’s end, but instead things just keep getting worse.

The crew discover that they are actually duplicates of Voyager’s crew, not the real crew—but they still have the same memories and personalities that the real crew do. They are essentially still those characters, but they’re told that everything they believe and remember is fake. Their cells are degrading because they’re not really human. More major characters die. The crew try to reach a planet where they might survive, but they are chased off. They talk of trying to find Voyager to sample the real crew’s DNA as a way to remain human, but they have no way of locating the ship. Eventually they decide to head back to their home planet, where they may be able to survive—though potentially just as the non-sentient goo that they were before they became duplicates.

The illness gets worse. Everyone is affected. Eventually Janeway dies, as do most of the crew. Harry Kim, the most junior of the ship’s senior officers, becomes acting captain, as the highest-ranking crew member still alive. The crew now have basically no chance of reaching their home planet in time to be saved. They decide to release a capsule containing their records and logs, so that their existence might at least be known and remembered by someone. This doesn’t even work, and the capsule is destroyed. They see a ship (which turns out to be the real Voyager) and decide to send a distress call. They’re 10 minutes away from being able to communicate with them. But nope, they all die before they get close enough, and no one knows they ever existed. The end.

The counterpoint to the darkness in this episode is simply that the characters never give up. How do you deal with your own mortality—with knowing that you’re about to die? Usually, one could argue that there is comfort to be found in knowing that the people you care about will live on, but in this case everyone these characters know and love is going to die as well. The next step might be to find solace in your legacy—in knowing that there is some record of your achievements, that someone will remember your existence. The characters are denied this too. This raises the question of whether meaning can be found in a life that’s unobserved.

The crew become the proverbial tree falling in the forest—did they really make a sound if there was no one around to hear them? Another place you might turn to find meaning in your mortality is philosophy, particularly concerning moral theories—did you at least live a good life? One school of thought here, utilitarianism, claims that it’s the consequences of our actions that matter, therefore you have only done good things if your actions have resulted in good consequences. Given that the crew’s actions in this episode fail to save any of them, and that they will leave the world without having made any significant impact on it, utilitarianism would seem to deny that anything they did was good or meaningful at all.

In that case, what’s the point? Should they never have bothered to do anything? Should they just give up? They don’t. They keep going, trying to save themselves, living according to their values, right up to the end. This brings to mind a moral theory that opposes utilitarianism—virtue ethics. Virtue ethics states that what’s important is always acting in line with your principles—doing the right thing for the sake of doing the right thing, no matter what the consequences are. This is what the duplicate crew does. This is what makes their lives meaningful, and what gives their story a glimmer of hope. This might also inspire anyone watching the episode who is struggling to find meaning in their own life, or who can’t see any hope for the future—there is meaning and hope in simply living according to your values, and refusing to give up.

“Course: Oblivion” can be seen as a microcosm of the whole show. Voyager’s crew must continue to find meaning in their lives, and reasons to keep going, despite being 70,000 light-years away from the rules of their society and the expectations of anyone they know. They continue to live by the principles, rules, and regulations of Starfleet, despite the fact that Starfleet Command have no idea that they’re still alive, and that they might never find out about the crew’s actions in the Delta Quadrant.

In the show’s pilot, Janeway and Chakotay decide to merge their two crews, and to run Voyager as a Starfleet ship. Perhaps they do this as a way to encourage the crew to stick to their principles while navigating a seemingly hopeless situation, alone and unobserved by any higher authority. Perhaps they know this is the best way to stop crew members from giving in to desperation and doing something they’ll regret in a bid to get home, or from giving in to depression and no longer trying to do anything at all.

One other way Voyager’s crew maintains hope is through fantasies, with crew members regularly using the holodeck for escapism and inspiration. This reflects the fact that in real life many of us find strength and solace in TV and movies, including Voyager itself. Tom Paris uses the holodeck to indulge his obsession with the 20th century, while Janeway talks through her ideas with Leonardo da Vinci and enjoys a romance in the Irish village of Fair Haven. The Doctor and Seven of Nine each explore their burgeoning humanity on the holodeck, and Neelix uses a holographic fairytale to distract the young Naomi Wildman when her mother is injured.

Voyager’s premise has its characters stretched almost to their breaking point every day, as they try to cope with life stranded in the Delta Quadrant—they’re far from home and forced together by circumstances, with no reinforcements to call on. In that state that we see their decisions, their strengths, and their vulnerabilities. This makes for a much more emotionally resonant show than other Star Trek installments. It also makes for intriguing characters and dynamics that could only exist in this situation.

While they may have started out as enemies with ideological differences, now that they’re in the Delta Quadrant, petty distinctions like Starfleet, Maquis, or criminal just don’t seem to matter. What matters is surviving their ordeal, finding a way home, showing up for each other every day, and working together for the good of the entire crew.

Because of the unusual circumstances, only three of Voyager’s main characters and senior officers—Janeway, Tuvok, and Harry Kim—are genuine Starfleet officers in good standing. This is a unique and fascinating deviation from other Star Trek shows. Of those three, only Janeway and Tuvok have any experience. Harry is young and on his first mission, a fact which makes his getting stuck in the Delta Quadrant that much more heartbreaking, and his personal journey that much more interesting to watch.

Two other main characters, Chakotay and B’Elanna Torres, are Maquis rebels, who Janeway grants positions of authority in order to make the merging of the two crews go more smoothly. Admittedly, Chakotay is a former Starfleet officer with strong principles, while B’Elanna is a talented engineer who spent some time at Starfleet Academy, but it’s still an unusual and interesting dynamic. Of course, both Chakotay and B’Elanna prove to be more than worthy of Janeway’s trust and become vital members of the crew.

Another main character, Tom Paris, is a prisoner—a former Starfleet pilot who was fired for causing an accident and lying about it, and who then joined the Maquis as a mercenary before being captured. He attains his position as Voyager’s pilot because the original pilot is killed on arrival in the Delta Quadrant, leading Janeway to appoint Tom as her replacement. However, he also proves himself by going above and beyond to help both Voyager’s crew and the Maquis crew. His overall story arc is one of redemption, and while he has his struggles, he certainly earns his place as a valued crew member.

Two more main characters, Neelix and Kes, are aliens from the Delta Quadrant who have never even heard of Starfleet or the Federation before, but who can provide valuable guidance to the crew on what to expect in this region of space. While they would surely never be allowed to join a regular Starfleet crew, the circumstances again allow for an exception to be made. They each offer a different perspective, and each have their own skills to contribute. They soon fit in with the rest of the crew, becoming an undisputed part of the Voyager family.

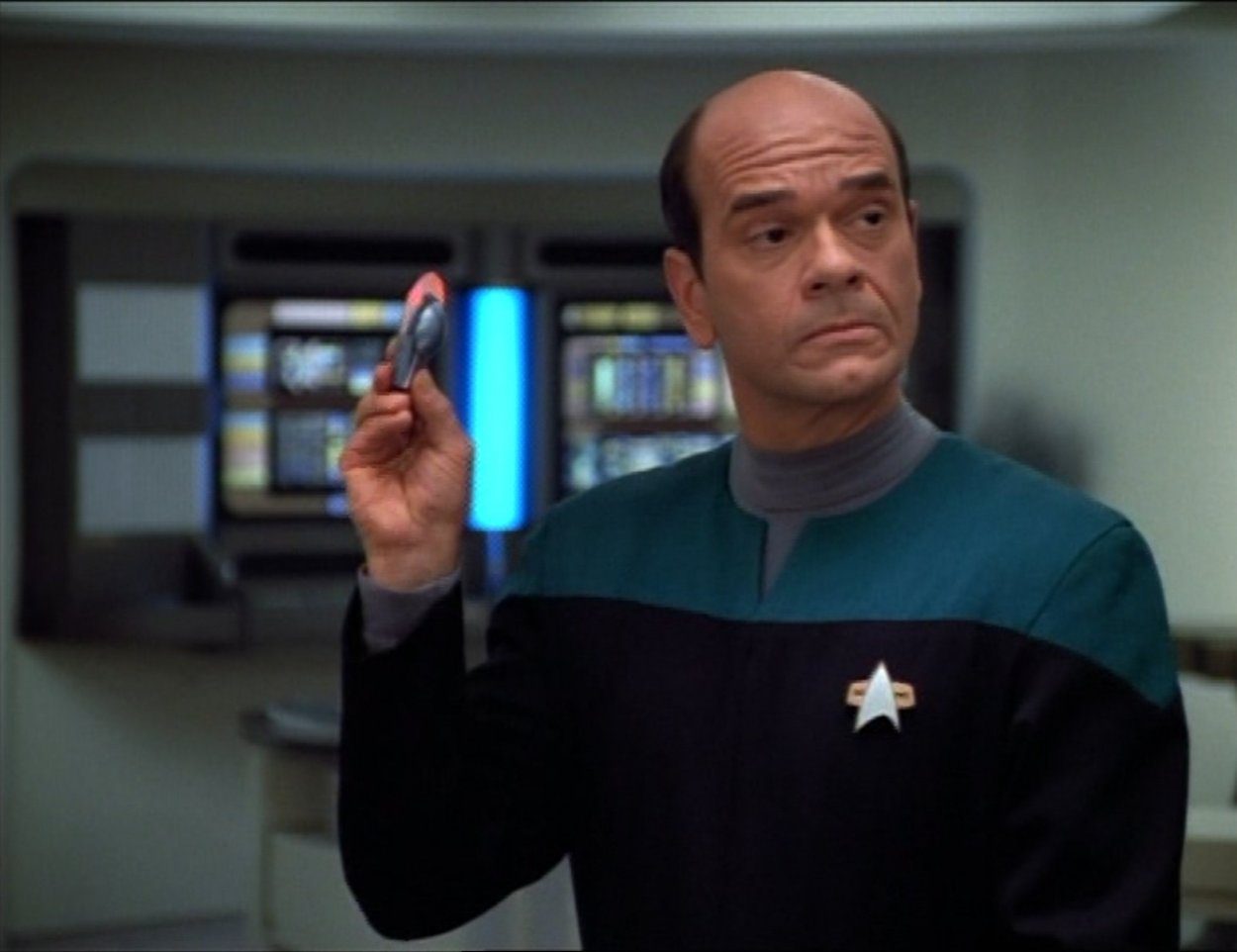

One of the most interesting characters is the Doctor, an emergency medical hologram designed to be used only in the short term, who soon finds himself pushed to extremes—and way beyond. The Doctor becomes a fully-fledged member of the crew, and the ship’s chief medical officer, after all medical personnel are killed in the pilot, and Voyager is stranded in the Delta Quadrant with the closest replacements 70,000 light-years away. The Doctor evolves way beyond anything his original programming intended, both in terms of his abilities and his humanity. Like Data before him, he challenges pre-conceived notions of artificial intelligence and of what it means to be human.

At first the Doctor struggles to be taken seriously or respected by the crew, who think of him as just a computer program, but he soon proves he’s more than that. He’s an individual in his own right, and he consistently goes above and beyond even the duties of a chief medical officer in his heroic efforts to help the crew. A great example of this is the episode “Message in a Bottle”, in which the Doctor is transmitted across an alien relay system to a Starfleet ship in the Alpha Quadrant, in hopes of finally communicating Voyager’s situation to Starfleet Command.

When the Doctor arrives on the Starfleet vessel, he finds that it has been taken over by Romulans, and not a single Starfleet crew member remains alive. Rather than giving up, he activates the ship’s own emergency medical hologram, and persuades him to work with him to defeat the Romulans and take control of the ship. They eventually succeed, and the Doctor is able to make contact with Starfleet Command before being sent back to Voyager—a huge milestone in the series, as this is the first time the crew have been able to tell anyone back home that they’re still alive and stuck in the Delta Quadrant.

Throughout the series, hanging over the Doctor’s head is the idea that he’s essentially expendable. No matter how much he evolves and becomes part of the crew, he’s still inextricably tied to the ship itself, and exists only because of Voyager’s position in the Delta Quadrant. If they do ever get home, will he simply be erased or reprogrammed? What else could be done with him? Despite these questions, he’s always willing to cooperate with the crew’s goal of getting home.

The threat of the Doctor’s program being erased for strategic purposes is also something that’s raised fairly frequently, but this never stops him from going along with whatever plan it’s a part of. This includes the events of “Message in a Bottle”, during which there’s no guarantee that his program will be successfully transmitted to the Starfleet ship, or that he’ll be able to return to Voyager.

Another example is in the two-part episode “Scorpion”, when the Doctor develops research that the Borg desperately need, and Janeway uses this as leverage to get the Borg to cooperate with her, threatening to destroy the Doctor’s program (and the research along with it) if the Borg don’t stick to their end of the deal. The Doctor is a character whose engaging inner conflicts and dynamic with the rest of the crew simply couldn’t exist on a regular Star Trek show (or Starfleet ship), but the extraordinary circumstances of Voyager allow him to flourish.

The final main character, Seven of Nine, is a former Borg drone who would never normally be trusted on a Starfleet crew, but again, in this case circumstances demand it. Janeway and Chakotay decide to sever her connection with the Borg in order to protect their crew, thus making her their responsibility as she starts to regain her humanity. A fascinating and unique character, Seven is highly intelligent, but she’s an outsider who often rubs people the wrong way. She doesn’t fully understand others’ or her own humanity, but she is essentially a good person trying her best.

In the episode “The Raven”, Seven follows a Borg signal in hopes of reuniting with the Collective, but it ends up leading to the ship she lived on as a child with her parents, bringing up the traumatic memory of when she was assimilated. On this and several other occasions, Seven is forced to confront the fact that she has no hope of ever being fully human or fully Borg again. Her Borg side sometimes drives her towards the temptation to rejoin the Collective at any expense, but her human side drives her towards integrity and loyalty, as she is able to find hope in something new—being a member of Voyager’s crew.

Throughout the series, Janeway and Chakotay manage to keep the crew in line based solely on their personal authority and inspirational leadership, with no wider organization around to back them up and no real power to enforce Starfleet protocol. This is an impressive feat. Because Janeway has to maintain this authority around her crew, she can never truly let her guard down with them, but unlike most Starfleet captains, she has no contact with any friends or family outside of the crew. The only person in her life close to being her equal is Chakotay, and so he becomes the only person in the world that she can allow herself to be vulnerable around, to let off steam and be herself with.

He also shares the burden with her of taking responsibility for the crew’s survival in the Delta Quadrant—an immense pressure that no one else could fully comprehend. This makes the relationship between the two of them far more interesting and intense than any other relationship between a Star Trek captain and their first officer. While Janeway maintains the professionalism necessary to lead the rest of her crew, she and Chakotay rely on each other emotionally in a way that’s endlessly compelling. It’s unconventional for Starfleet officers, yet it’s completely understandable given the circumstances they’re in, and it’s fascinating to watch their relationship unfold.

When they disagree, as in the episode “Scorpion”, during which Chakotay opposes Janeway’s decision to form an alliance with the Borg, they’re both devastated by the impasse, and struggle to find a way to work through it without any higher authority to guide them. They do eventually manage to work it out, though—they always do. Throughout the show they navigate their way through being former enemies, trusted colleagues, and best friends, with a dash of romantic tension always seeming to bubble close to the surface.

While Star Trek as a whole is a wonderful franchise based on a great idea, it’s my view that by daring to do something different, and taking that idea in a totally new direction, Voyager perfected it. Voyager shows us how to stay hopeful even in the most hopeless situation. Its darker elements are the catalyst for so much of what makes it unique, and its characters, relationships, and themes will always be utterly captivating to explore.