This article contains heavy spoilers, so if you haven’t seen the film, you might not be able to follow it as well. The fairy tale allegory of Jennifer Lynch‘s Chained (2012) necessitates some plot exposition in order to explore the morals, and allude to the nature of evil described within the film.

Chained isn’t an easy film to watch. Unless your dating life unfortunately resembles my past dating life, it probably won’t be the best date film. However, if you like beautifully shot, flawlessly acted and directed, and incredibly on-point and unflinching metaphors that pack a brass-knuckle emotional punch, this is the film you’re looking for.

A passionate advocate for kindness and compassion, only the brilliant director and screenwriter Jennifer Lynch could have made this film.

As any survivor of abuse or trauma can attest, it’s incredibly difficult to focus so acutely on the relationship between trauma and fear, and how tightly bound the two are. Through abuse and trauma, those chains forge in the fire of will to survive, and lack of alternatives. With Chained, Jennifer Lynch forces the viewer to focus on those things, and dive deep into them.

When Bob (played by Vincent D’Onofrio) abducts (so far unnamed) Rabbit and his mother (played by Julia Ormond), he’s driving a taxi with “Comfort” painted on both the bumper and on the roof light. Nine-year-old boy Rabbit listens from the back of the parked cab as Bob tortures and murders his mother, whose last words to Rabbit tell him to cover his ears, and that everything would be okay. The bright yellow paint will be the last bright color on the director’s palette.

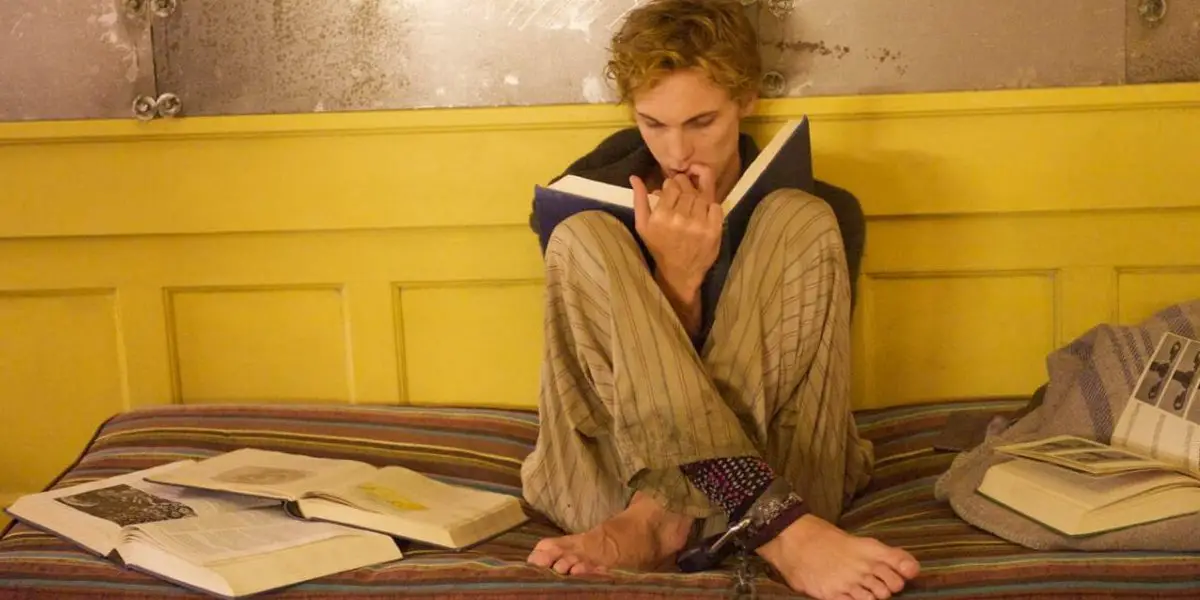

When Bob pulls him from the relative safety of the cab, Rabbit fights and fails. Thus physically dominated and emotionally devastated, Rabbit sits on an earth-toned cot in the kitchen and sobs while Bob watches television in an undershirt and shorts. The walls are sickly, muted greens, yellows, and browns. Lamps throughout the house produce weak light, creating ominous, soft-edged chevrons up and down the walls. No more of the bright colors of childhood. No more relative comfort of the cab.

Bob lays down the law; Rabbit has only one job: obey and serve. Everything—down to food and drink—are under the control of the captor, who is the embodiment of trauma. Rabbit is to help Bob with murders and disposal of women’s bodies. He’s to help with the examination of newspapers for mentions of the murders to include in a scrapbook. Bob tells him, “From now on, this is your world. It is only you, me, and them (victims). I will call you Rabbit.” Any deviance from the rules will result in a beating.

At this point, the boy has been stripped of his family, stripped of his previous life, stripped of anything resembling comfort, and now stripped of his name. Instead of his name, he’s now referred to one of the universal symbols for fear. A rabbit, in its skittish nature, trying to avoid the wrath of the predator.

Rabbit’s one escape attempt leads him to the roof of the house, and into the bright glare of the sun. Of course Bob waits for him, encouraging him to “let it out.” Rabbit screams pointlessly into the empty country air for help. He still has hope.

Trauma, however, won’t let that stand.

Bob yells, “I know every move that you make. Everything you do, I let you do….. You are so f*cking predictable, and a f*cking embarrassment!” As a child, of course Rabbit believes this. He attempts to run. Bob clocks him in the head with a stone and knocks him unconscious.

There goes hope.

After his failed escape attempt, Bob chains Rabbit inside the house, and watches him via surveillance cameras while Bob hunts his prey.

There goes freedom. There goes what little chance at privacy Rabbit had.

What is left for Rabbit, then? What is left of a victim when the instigator of trauma has robbed him of everything? For Rabbit, he’s forced to participate in inflicting pain and trauma on others. Bob forces him to play card games with driver’s licenses stolen from victims.

Through flashbacks, we learn more about the severe sexual abuse and trauma that contributed to Bob’s evolution into Trauma Incarnate. Disturbing and frightening, these scenes tell us what we already know: some bad stuff happened to Bob. Bob probably wasn’t born a sadistic murderer, and his early family life certainly didn’t help him grow into Ghandi.

Most of us viewers live outside of the world of torture, rape, and murder, but this film serves the purpose of a dark fairy tale, and Jennifer Lynch doesn’t flinch in showing us the darkness of how an upbringing can go very, very badly. It’s an allegory, though, so there are opposing forces at play.

Once, like Rabbit forced out of the Comfort Taxi, we are forced out of what is comforting to us, there are forces, traumas, that can chain us to them no matter how vigorously we fight against them. Once we are linked so tightly by invisible chains to that which causes us fear, causes us anger, and provides nothing in the way of love, light, color, and comfort; that which we are bound to, that which dominates and controls us, is what we become.

Bob forces Rabbit to become a murderer, but only after removing his chain. Rabbit has more freedom than he has ever had in his life with Bob, but instead of using his weapon to attack his tormentor, he obeys. He becomes a man who tells Bob, “I want to hunt.” Bob’s response is to reward Rabbit with a chair of his own for watching television. Bob believes Rabbit’s transformation into Trauma Incarnate approaches completion, and he acts oddly proud.

If the things that entrap and chain us, like physical, emotional, and sexual abuse, and the people who inflict them upon us, positively reinforce that same behavior in us, they’re prompted to bring us into their circle. Inclusion into any circle, especially one which wields such power over us, can be intoxicating and appealing to anyone. Once Bob thinks Rabbit’s murdered his first woman, Bob trusts him, elevates him, calls it his “graduation.”

Relying on Rabbit’s supposed elation at being included and ostensibly freed from his chain, Bob rewards Rabbit by bringing him into the taxi he used to abduct Rabbit and his mother. That’s the taxi labeled “Comfort.” Upon seeing the cab, Rabbit remembers his mother’s voice with perfect clarity. For the first time since Rabbit was nine years old, Bob offers him comfort because he believes Rabbit is finally like him.

Of course Rabbit didn’t really commit the murder, and uses his murder “lesson” as another escape attempt. Ultimately, Rabbit finds his way to killing Bob and finding his real father. Upon their first meeting, his father rewards him with his name, Tim. Not is all it appears to be, though, as Tim’s father had paid Bob to kill Tim’s mother and Tim. When that father becomes violent toward his current wife, Rabbit uses a glass sculpture resembling the infinity symbol to bludgeon him to death. So, cycle of abuse broken?

This is a fairy tale, and the ending is less than happy for everyone involved. Rabbit does have to make a couple of kills, but they were both to save lives by killing a pair of evil brothers. By killing first Bob, then his own father, Rabbit has seemingly ended the cycle of trauma in his own family. He drives the Comfort cab back to Bob’s house the only home he’s really known. Credits roll over the sound of the closing garage door, and Rabbit getting himself a drink from the refrigerator. He’s only serving himself now, with bodies buried in the crawl space beneath him.

Delving further into allegory, and aside from abuse, the things that chain us in our world are legion, and can all be used to divide us from our best selves: addiction, societal hierarchies, political fervor, narcissism…the list goes on and on.

Above all, what we see in Bob is a complete lack of empathy and compassion for the women he victimizes and for Rabbit, his slave. Bob is the villain, the vessel of evil. He shows us the true nature of evil.

This is the true nature of evil in Chained: the will to inflict our pain and trauma on those around us, the absence of whatever force it is that allows us to be kind to others. The moral of the fairy tale as I see it is this: Once we shed our chains to the fears, the traumas, the anger that form us, we are offered the choice to either continue those destructive cycles, or to spread real comfort through kindness and empathy.