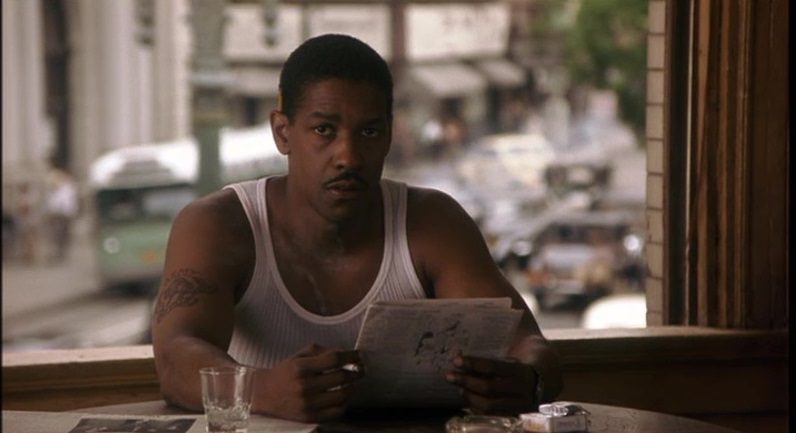

Overlooked in a flurry of mid-1990s neo-noirs was one intriguing experiment that but for its commercial failure might have launched an ongoing franchise. Devil in a Blue Dress, director Carl Franklin’s stylish adaptation of Walter Mosley’s 1990 debut novel, made for a thought-provoking contribution to Denzel Washington’s rapidly growing cadre of stand-up good guys navigating a corrupt world. As Ezekiel “Easy” Rawlins, Washington exudes a laid-back charm that hides a wiry strength. Investigating a disappearance that becomes a murder case in which he is also a suspect, Easy peels back the layers of a mystery that is as much about race and color as it is about the crime being solved. Franklin’s direction makes Devil in a Blue Dress both a commentary on the blinding whiteness of the film noir idiom and a treatise on an idealized, harmonious vision of a racially diverse postwar America.

Historically, film noir in its original incarnation was—ironically so for an idiom so drenched in darkness—comprised nearly entirely of white characters, and, by extension, white directors, producers, and writers. The classics of the genre that became so recognizable and imitated in the 1940s, from The Maltese Falcon and Double Indemnity to The Killers, Out of the Past, The Big Combo, and Laura all evidence so many of the same signature components: the down-and-out antihero, the investigative narrative fractured by flashbacks, the labyrinthine plots full of twists and turns, the voice-over narration, the femme fatale, and the evocative, signature chiaroscuro of low-lit urban street corners, shadowy interiors, and reflective surfaces, all designed to unsettle and disorient. Trenchcoats and tight lips, fedoras, handguns, you get it.

Nearly wholly absent from any of those signature films, all so obsessed with the absence of color, were any black characters, except at their narratives’ periphery. Far outside the studio system and following the lead of Oscar Micheaux, Spencer Williams was knocking out low-budget noirs like Dirty Gertie from Harlem U.S.A. (1946) just as a few opportunities began to emerge in Hollywood: Canada Lee and James Edwards played key roles in Body and Soul (1947) and The Set-Up (1949), respectively. The following decade saw Sidney Poitier and Harry Belafonte take the leads in No Way Out (1950) and Odds Against Tomorrow (1959). But by and large these remained exceptions, and even the most celebrated neo-noirs of the 1970s–Dirty Harry, Chinatown, Taxi Driver–relegated black characters to the sidelines as unnamed pimps or marks, if they appeared at all.

Meanwhile, Melvin Van Peeble’s reactionary, revolutionary Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song made way for the black heroes Shaft, Superfly, Slaughter, Coffy, and others, whose vigilante heroes evoked the noir narrative with little of its signature stylistic flair. The studios were far less interested in any artistic merit or cinematic expression than they were the box-office receipts most blaxploitation films might garner. In the 1980s, the successes of Blood Simple and Body Heat led to films using the noir idiom as a means of highlighting new questions about race, gender, and class with an increasing explicitness. In the following decade, Basic Instinct, Bound, and The Last Seduction followed the Body Heat formula but amplified its sexuality, and though they didn’t make for big hits, the noir-adjacent One False Move, Deep Cover, and Clockers suggested ways that film noir’s urban labyrinths might translate to New Black Cinema.

Released in 1995 alongside a flurry of similarly stylish, sexy, neo-noir thrillers, Devil in a Blue Dress—adapting a black writer’s highly successful debut novel, helmed by an up-and-coming black director, and starring the era’s bona fide black box office star leading a mostly-black cast—aimed to address the longstanding colorblindness of film noir’s dark streets and darker themes. Mosley’s novel rebooted the hard boiled fiction of Raymond Chandler’s L.A. from the perspective of the black man who had been until then nearly absent from the genre, and in doing so it boldly put questions of race and color at its forefront.

Its opening credits sequence suggests a busy, urban, nighttime narrative perfectly suited to neo-noir, with the cast’s and crew’s names superimposed over slowly panning details from Archibald John Motley Jr.’s 1949 oil-on-canvas Bronzeville at Night. Black men and women dressed in dapper fineries and workday duds crowd Motley’s energetic kaleidoscope, set to the tune of T-Bone Walker’s “West Side Baby.” The images may be set in Chicago, where the South Side Bronzeville neighborhood was known as the Black Metropolis, but they and Walker’s blues are wholly authentic to the African-American experience of Mosley’s fictional Easy Rawlins’ adventures in Los Angeles. The opening sequence paints a picture to which the film as a whole does not stay quite true, though, as Devil soon settles for some rather generic scoring by Elmer Bernstein and a scenario less lively than Motley’s.

Largely eschewing the bluish nighttime exterior of Motley’s Bronzeville, Franklin and cinematographer Tak Fujimoto opt instead for a sepia-toned depiction of postwar L.A. immersed in a gauzy past of city streets, saloons, and piers. The protagonist, Easy, recently and unjustly fired, is proudly the owner of his own home, suggesting a thematic focus on the rights of minorities. (In a notorious and well-publicized example, the State of California is returning to its rightful heirs a multi-million dollar beach property seized from its black owners during the Jim Crow era.) “My name’s not ‘fella’,” Easy growls: he’s determined to safeguard his property and identity.

Soon enough, the plot is underway, and within minutes, Easy is done an apparent solid by his friend the saloon owner Joppy, who introduces him to DeWitt Albright, who explains the assignment: find a a missing white woman, Daphne Monet. Easy’s search leads him to Coretta, a girlfriend of a friend of Easy’s and supposedly a confidant of Daphne’s. The requisite acts of sex (Easy beds Coretta) and violence (Coretta is found murdered) complicate the narrative and motivate the film’s most overt film noir tropes, including Easy’s investigation, flashback narration, and the appearance of an apparent femme fatale.

A number of the best and most archetypal films noir featured plots so convoluted they were nearly incomprehensible: Laura, The Big Sleep, Out of the Past, The Killers. In noir the plot is itself often something of a MacGuffin, a means of motivating the essential tropes and evoking the paranoia and dread so central to the style. Certainly the plot isn’t what appeals most about Devil with a Blue Dress. We learn, eventually, that there is indeed a villain and his wrongdoing is heinous: unscrupulous mayoral candidate Terell is a pedophile, and Easy eventually discovers photographs incriminating him. But given that we never know Terell’s victims or witness any indication of the crimes or their consequences other than the photos, this aspect of the mystery is little more than a narrative exercise.

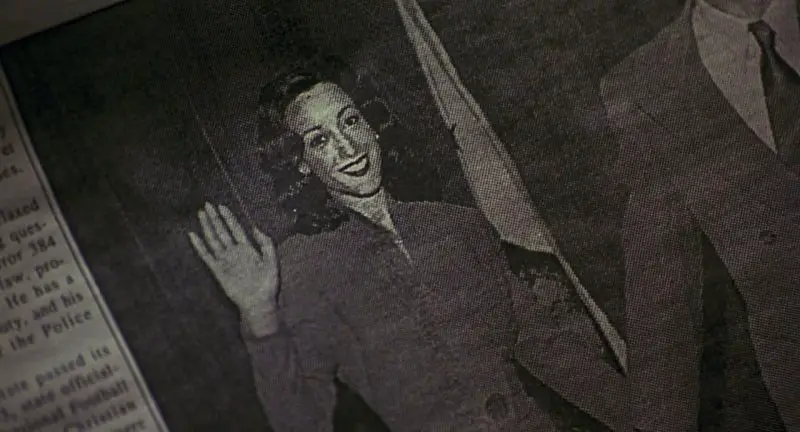

Instead, the real mystery of Devil with a Blue Dress is not so mundane as a grievous crime committed by a despicable villain. The complex web of crime in which Easy finds himself turns more than anything else on a surprise revelation: Daphne Monet is actually mixed-race but has been passing for white. Before her disappearance, she was engaged to Terell’s rich white mayoral opponent and has acquired the photographs proving Terell’s pedophilia. But again, neither the film nor its protagonist is particularly interested in Terrell’s crime against children. Instead, the film and its characters are consumed by the vexation posed by Daphne’s passing.

That Daphne is born to mixed parentage and has passed in society as white precipitate the confusion, double-dealing, and death that marks the perverse world Easy has entered, and while Easy is no innocent, Daphne’s world of secrets, affairs, crimes, and double-dealing is foreign to him: his expressed desires are to keep his day job, pay his mortgage, and tend to his rose garden. Like in so many great films noir and neo-noirs from Laura, The Killers, and Out of the Past to Chinatown and Body Heat, Devil in a Blue Dress concerns itself with an investigation into identity. Yet unlike each of those here it is racial identity and its occlusion that serves as the film’s central preoccupation.

It’s fascinating, of course, that the question of Daphne’s racial identity becomes more consuming than the pedophilia perpetrated by the film’s ostensible villain, Terell. But he is a secondary character and his victims never onscreen. (That fact, in my opinion, makes Devil with a Blue Dress a little less compelling as a mystery than, say, Chinatown, in which both victims and villain are onscreen alongside the protagonist for most of the narrative’s duration.) Daphne herself is no “devil,” but her secret is understood to be so disruptive to the maintenance of racial categorization that its outing must be contained.

That in the diegesis of the film Daphne Monet’s identity is presumed at first to be white and then later revealed as mixed poses an interesting conundrum in terms of adaptation. Mosley’s novel presented Monet as a “light-haired” woman assumed by Albright and Easy to be white. Franklin’s adaptation avoids any reference, visual or verbal, to blondeness. But in casting Jennifer Beals, whom viewers might well have known to be of mixed parentage herself (her father is African American), Franklin took a calculated risk: while Beals was of a mixed heritage just as was the character she was to play, would audiences thus presume her character to be similar to her portrayer’s—and thus the film’s major revelation to fall flat as a consequence? “I was concerned it would tip off the secret,” says the director on his DVD commentary track.

Devil in a Blue Dress, from its title to its protagonist, visual style, and narrative tropes locates itself squarely in the idiom of film noir. Beals, though ostensibly the film’s titular character, features in the film’s marketing materials, but in silhouette, dwarfed by star Washington’s close-up: the title and campaign both posit her as a figure of mystery. She may be garbed in a blue dress, but she is revealed to be something other than the traditional femme fatale Easy Rawlins and viewers assume, and she is no “devil”—at least not in the ways of a Phyllis Dietrichson or Matty Walker, who pulled their male dupes into their duplicitous webs and eventual demise.

Daphne Monet’s character is less the femme fatale synonymous with noir than she is a disguised version of the “tragic mulatto/a” character, one of Donald Bogle’s stereotypical categories of African American cinematic representation. Often attempting to pass for white, the fair-skinned mulatto/a would endure tragedy due to their mixed heritage, with audiences understanding them to be likable, sympathetic characters, perhaps most famously evidenced by Susan Kohner’s character in Douglas Sirk’s version of Imitation of Life. Daphne, it is suggested on several occasions early in the film, is transgressive, a (presumedly) white woman preferring black sexual partners, and the film depends on its viewers associating such transgressive activity with that typical of the femme fatale.

But whether those intimations are true of her character becomes moot. Albright implied that as a white woman she was transgressive in preferring the company of black lovers: “She likes jazz, pig’s feet, and dark meat,” he tells Easy – rationalizing his need for a black man to investigate her disappearance – and for a moment when Easy finds Daphne, the two exchange a brief parry of sexual repartee. But little comes of it, and with Daphne’s confession it becomes clear that her “transgression” is not that she is a white woman who prefers black men but that she is a (half) black woman passing as white.

As Easy’s investigation accelerates, the dead bodies pile up: Coretta, first, then the blackmailer McGee, saloon owner Joppy, and finally Albright and his goons. Not, though, Daphne Monet. Just as a traditional film noir’s narrative would punish its femme fatale with death or imprisonment, Devil‘s cannot abide Daphne Monet’s ongoing presence or deception. A threat to the mayoral race, to the good of society, and to Easy’s welfare, she is exiled, sent to an offscreen purgatory where she will remain forever offscreen and irrelevant to the other characters’ fates. Even the film’s sepia-drenched background images are juxtaposed with the unnatural blue of Daphne’s dresses, creating a starkly oppositional contrast that calls into question her “belonging.” The mulatto/a figure in film and literature typically vexes simple classification and serves in the person of Daphne Monet as a mystery to be solved—by Easy Rawlins and by viewers.

Despite its generally positive reviews, especially for Franklin’s direction and Washington as its star, Devil with a Blue Dress met with disappointment at the box office. It placed third its opening weekend, way behind David Fincher’s Se7en, fell quickly to seventh, and ultimately earned only $16 million domestic against its $27 million budget. While Washington had become a reliable lead by the mid-1990s, having earned an Oscar for Best Supporting Actor in 1989’s Glory and a nomination for Best Actor for Malcolm X a few years later, his presence above the title was hardly a guarantee of commercial success. There is next to no heat between him and the distant Beals, who exchange but a single line and brief smolder of the sexual attraction most neo-noirs promised. As the trigger-quick Mouse, Don Cheadle earned buzz for his scene-stealing sociopath, as did Fujimoto for the cinematography, but the film was rather quickly forgotten except to Washington’s and neo-noir’s most fervent devotees.

One wonders if the film’s thoughtful, complex examination of racial passing and prejudice at the expense of simple titillation and puerile provocation might have kept it from reaching a wider audience. Had Devil with a Blue Dress fared a bit better with audiences, it might have become the Easy Rawlins franchise some imagined. Mosley continued with the character, having written three more Easy Rawlins books by the time of Devil’s release and another ten (and a collection of short stories) since, continuing to focus on color as a prominent thematic. Forbes recently reported that Amblin Entertainment will be producing a new series based on the Rawlins books, executive-produced by Sylvain White: the time may be right for a streaming series to explore the complex, compelling character with a little less of the box-office pressure Franklin’s adaptation faced.

At the end of Devil with a Blue Dress—mystery solved, villains killed or jailed, Daphne exiled and himself a free man—Easy returns to his home neighborhood, reflecting upon the peaceful life it provides him. Cars loll by, kids play in yards, roses grow in their gardens. The vision is one of peace and harmony, a postwar utopia of home-ownership, safety, and security with everything in its place. There are, we are to assume, no pedophiles, no blackmailers, no passing-as-white-women, no immediate threats to the social order. Easy’s utopia may be temporary, but his world is one worth exploring further, and if and when Sylvain White’s reboot makes it to air (or cable, or streaming), I’ll have hand on remote, ready to watch.

The only thing keeping this film from being noir is the color of the femme fatale’s dresses. The lurid subject matter, race included, falls well within the defines of true film noir.

I would add that Mouse is Easy’s alter ego. He exists to exhibit the traits the protagonist wishes he could outwardly exhibit and not lose himself in that world. That said, Mouse is not a “real” person. When the sub character says you killed that old man he means EZ killed him.

Any recognition of Mouse at any other time is a conjuration of EZ’s imagination to subvert blame for his ability to kill at ease and without empathy. Like in “Fight Club” our protagonist is schizophrenic. His split personality is brought on by his experiences in WWII. As a necessity of war to stay alive you have to be able to unravel the mortal coil of the enemy without remorse.

I am a fan of noir cinema and think this is one of its finest examples. I don’t think it fits in “neo-noir” because the timeline is late 1940s. That’s my two cents.

Thanks for reading and commenting, C Moore. I don’t believe I have ever heard your take on Easy and Mouse. In Fight Club the narrator is famously, unarguably reliable and his schizophrenia made clear onscreen. I don’t recall any actual evidence in DWBD of Easy’s unreliability or schizophrenia, but it’s not beyond the realm of possibility a veteran of WWII could have such. Interesting take.

I’m not that interested in labeling the film noir or neo-noir. It’s clearly less overtly “neo” (and more retro) than other work of its era, with its classical cinematography, period music, and content (excepting its obsession with race, which is pretty important to the narrative; it’s not the color of the dress that’s the transgression). In these respects aside from race the film is much like Chinatown, which nearly everyone characterizes as neo-noir. Many neo-noirs are set in the late 1940s.

Thanks again for reading, and I’ll give your take some more thought next time I rewatch the film. Here’s hoping the rumored Easy Rawlins series comes to fruition!