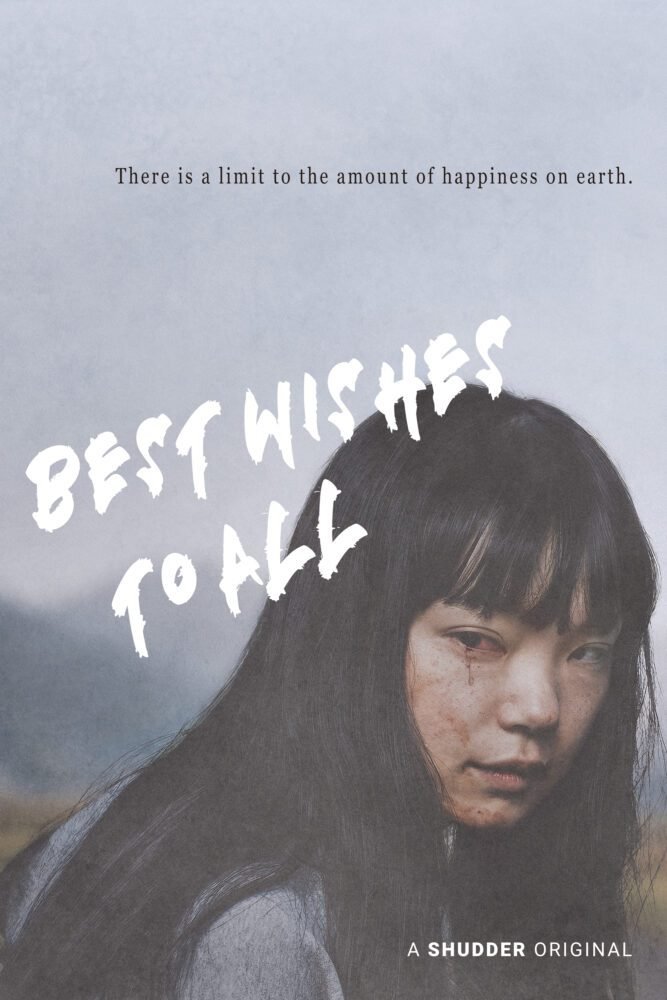

Best Wishes to All is the deeply unsettling and disturbing gut-punch of a film we all need right now, and that’s not hyperbole. I first saw Yûta Shimotsu’s film, based on his short of the same name, at the Boston Underground Film Festival a couple of months back, and I left the theater stunned at how refreshingly bold the film’s subtextual social commentary was when paired with the director’s cynical facade. The film doesn’t mix metaphors and offers neither bemusement nor remorse for its highly divisive story on what may be required to achieve a lifetime of happiness. It’s a bleak and chilling offering from Japan that also hits incredibly close to home.

Shimotsu begins this story with an innocent child on vacation at her grandparents’ house outside of the city. Though the scene is brief, there’s an inference of her fondness for the sunlight-drenched place, where meals are better with family, and her grandmother teaches her how to sew. Late one night, the child awakens to the sound of movement upstairs. Undisturbed by the prospect of ghosts or ghouls, she goes to investigate. A slightly opened door reveals the sounds of strained breathing, becoming more labored with every approaching footstep. The scene ends before Shimotsu gives away his premise, steeling a challenging concept into the back of the audience’s mind as they’re teased with inferred malevolence. The girl wakes up in her apartment from a locked-away memory, suddenly buoyant in her subconscious, and on her upcoming visit, she will discover the shocking truth.

As far as mysteries go, the first five minutes of Best Wishes to All are enthralling. Alerting the audience to very little, Shimotsu sucks us into the gravity of something evil lurking behind the closed doors of the nurse’s grandparents’ home. Like the young unnamed granddaughter (Kotone Furukawa) in the movie, the audience, too, is plagued by the thirst for the truth. What is happening in that house?

At first, unfolding a bit like M. Night Shyamalan’s The Visit, the audience considers that what they saw may be less nefarious than it appears. The idea that Best Wishes to All will take us through similar horrors of our forthcoming elder years crosses the mind, but Shimotsu pivots slightly. He is subtly alluding to the state of Japan’s elderly, albeit indirectly, as the movie evolves into a dread-inducing allegory of class exploitation.

According to a paper by Kenji Kushida, published by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Japan’s population is shrinking. As of 2021, thirty percent of its population is over sixty-five, a number expected to grow to thirty-five percent by 2040. This poses huge concerns for their cultural hierarchy, which reveres seniors and places them at the top. When retirement age arrives, the younger generation often takes care of the older generation, either by moving their parents in with them or by utilizing a senior care facility. However, the steady drop-off in population in people under fifty suggests there may not be anyone to care for Japan’s aging population, one way or the other, since there may not be enough working-age people in the next generation to meet the demand.

This real-world problem is what Rumi Kakuta and Yûta Shimotsu use as the catalyst for Best Wishes to All’s story, framing it through a feeling of needing to uphold the societal convention by any means necessary. What would you be willing to do to achieve an idyllic, long, and happy life? That’s Best Wishes to All’s fundamental question. When the granddaughter is finally told about what is going on in her grandparents’ house, her world is turned upside down. The film moves into folktale territory as morality and tradition collide. The granddaughter doesn’t want to adhere to this unspoken rule that promises prosperity at the cost of detriment to others, and runs about as far as she can. When she returns, the place has deteriorated into a house of uncouth horrors, where everyone acts as if everything is fine, despite strong evidence to the contrary.

Between the superficial happiness and masked depression displayed to everyone knowing this secret to a long, happy life to the despicable, blood curdling horrors the granddaughter witnesses, there’s a relatable suffocation in an entire society recognizing a dystopian trend within their culture, only to put on a happy face because the alternative is equally atrocious. There’s a whole lot more I would love to go into pertaining to the specifics of Best Wishes to All, but that essay will have to wait for another day, so you all have a chance to enjoy the film first.

Best Wishes to All will likely end up on my year-end favorites list since many scenes of it have lived rent-free in my head for months now. The cinematography is stunning. The creepy strangeness echoes Lynchian absurdity. The score is intense and brooding. And the philosophy embedded in the film’s conflicted ending will tie your stomach in knots.

Revealing a terrifying pentimento underneath an exquisite Japanese gothic, Best Wishes to All definitely won’t be for everyone. However, if you like deeply resonant and traumatic films that aren’t afraid to pull back the candy-coated veneer of what our society is, Best Wishes to All is a top-tier, must-watch, and an awe-inspiring start to Shimotsu’s directorial career.

Best Wishes to All streams this Friday exclusively on Shudder.