Everyone knows that the symbol of fire is central to Twin Peaks, but what does it symbolize? “Fire walk with me”—am I walking with the fire, or are we doing a “fire walk” together, and is that like walking on hot coals? Clearly, there is a spiritual dimension. And that spiritual dimension is perhaps never more at the fore of things than when Margaret Lanterman tells Laura Palmer that once a fire like this starts, it’s very hard to put out. The tender boughs of innocence she refers to are clearly the limbs of Laura’s soul. But then here in Episode 10, the reference seems much more literal—or material—as Leland flicks a match at the Sheriff’s station and recalls how Mr. Robertson used to ask him, “You want to play with fire, little boy?”

Like most (if not perhaps all) symbols in Twin Peaks, fire is not a signifier that refers to some definite signified. It isn’t a matter of one meaning being carried over into a new domain, where the sense of each is well-defined. The movement isn’t one of metaphor but metonymy, and we’re dealing not with analogies so much as a logic of floating signifiers which continually point us in the direction of further signifiers without ever coming to rest on some secure object of signification.

The fire is the one in Laura’s soul and the flame on the candles the One-Armed Man snuffs out as he recites his poem. It is the match Leland flicks that somehow lands in the ashtray across the room, and the force behind the burnt engine oil that Jacoby smells when he’s attacked at Easter Park. It’s what consumes Windom Earle’s soul in Episode 29 and what surrounds Mr. C at the end of The Return. It is physical and spiritual. The electricity that hums through the wires, the raging of the Trinity explosion…and the F-I-R-E of sexual excitement.

But this same structure holds all over Twin Peaks, which is part of why I love it so much and part of why is it so resistant to explanation while at the same time being so ripe for interpretation. It spurs thought and gives such food for it that the thinking never has to stop, or in principle cannot stop. To decide that you’ve “figured out” Twin Peaks is to have given up. At best, it’s a matter of reaching some kind of metastable understanding, a way of moving through the problems of Twin Peaks, conjugating them to arrive at a solution for the moment that will ultimately dissolve if you remain open to the movements of thinking that define the work. The narrative is self-undermining and clearly mined from the unconscious with its dream logic. There is metaphor, sure, but much more so there is metonymy, slippage, and synecdoche. And everywhere there are small differences between repetitions.

In Episode 10, Phillip Gerard is a mild-mannered shoe salesman. A week-and-a-half or so before—in Fire Walk with Me (where his name is apparently spelled with only one “L”)—he was raging at Laura and Leland from the window of a truck, ranting about how the latter had stolen corn and brandishing a ring that he would later throw into the train car for Laura at the end of the film (and what better symbol for the movement I am describing than this ring itself). Sure, his personality breaks when he is in the bathroom of the Sheriff’s station in Episode 10, and he emerges on the hunt for BOB because “without chemicals he points,” but what was this man doing for the week we did not see? It’s not clear how these events hang together with one another, and it only gets “worse” if we start thinking about Gerard in The Return. Because there, he seems to be pretty fully a being of the Lodge, whereas in Episode 10 and Fire Walk with Me he is very much presented as a flesh-and-blood man walking about in the world, perhaps selling shoes. Perhaps he is schizophrenic, or perhaps he is a magician who longs to see…does that mean he cannot currently see?

We could write a Twin Peaks article together through free association, like an exquisite corpse (wrapped in plastic). I know I’d like to read the result. Or one can dip into this sea of floating signifiers and start putting something together. Build a raft for yourself, and perhaps bring others along. And if I mention all of this in an article about Episode 10 it is because watching it again now, this episode seems like a kind of nexus for this neurological electricity, with sparks or synapses firing in multiple directions that won’t settle into some kind of substantial meaningfulness so much as they pull the rug out from under attempts to put thought to rest.

Donna visits Laura’s grave and suggests she wasn’t buried deep enough because her problems keep hanging around. Laura is dead, and yet she lives as this singularity around which all of the events of Twin Peaks circulate, and perhaps there is even a way of reading the orb scene in Part 8 of The Return through this lens, as it imbues the image of Laura with a mythic significance. Your Laura is gone, but it is this Laura that is not there that nonetheless exerts great influence, as an imago that persists beyond life and death.

Do you want to play with fire, little boy? Leland doesn’t say, “Do you want to play with BOB?” but the line seems present by its absence. Something is missing, but it’s not a page from Laura’s diary—the diary Donna finds when she visits Harold at the end of Episode 10. And in The Return Hawk will say that there is still a page missing, but could this be the page that Dale lets Donna keep a few episodes down the line after Harold has been found dead? Something is missing spiritually, but is it missing literally? I suppose it is, from Hawk’s point of view.

At this more literal level, Episode 10 presents us with a slippage when Albert presents evidence to Dale and Truman. He’s tested the cocaine from James’ bike to find a match with Leo’s and asks if Cooper gets the picture. He even gets the frame, but the fact is that Leo did not frame James by planting cocaine in his bike—that was Bobby, who we saw in Episode 7 do this and place a call to the Sheriff’s station pretending to be Leo. Lucy took this at face value.

So we shouldn’t make the mistake of thinking that anyone in Twin Peaks has it all figured out, whether we’re talking about Dale Cooper, or Hawk or Windom Earle when they talk about the Lodges later in Season 2. Certain things set in as taken for granted when we think about Twin Peaks, but Twin Peaks itself has a way of always leaving an opening to take them another way.

Dick Tremayne makes a point of telling Lucy, apropos of nothing, why he keeps his fork in his left hand as they eat at the Double R. It’s the European way, and I’m tempted to start spinning out some theory about the European ending to the Pilot of Twin Peaks as Episode 10 proceeds to show us Phillip Gerard emerging from a bathroom stall, looking upward and telling BOB that he’s after him now. Perhaps that was Cooper’s dream, or this is, or all of Twin Peaks is the dream of Dale or someone else. Take that path if you want to—perhaps it will lead you somewhere wonderful and strange as you lay it one stone at a time—but I don’t intend to follow.

A urinal in that bathroom of the Sheriff’s station is broken. What is the semiotic function of urination in Twin Peaks, and is it significant that here in Episode 10 we get a sign of its impossibility? Dale answers the call of nature when he is night-fishing with Major Briggs before the latter disappears. Ray tells Mr. C that he has to take a leak before he pulls a gun and shoots him on the side of the road. Deputy Bobby Briggs would like to talk more to the other Sheriff Truman, but his teeth are swimming…

It is noteworthy that people urinate in Twin Peaks, since this is not something we tend to see in other TV shows or films, so perhaps it is merely the fact of this that raises the question in my mind, and there is no real point or meaning to tease out from the scenes listed above, or the others I didn’t mention that involve nature’s call. And yet, here is a broken urinal, which we might take as an obstruction to that call of nature, a symbol of a fractured relationship between humanity and nature—and of course, Gerard does not pee, but writhes in the stall. He enters as a meek shoe salesman, but emerges as a spiritual warrior on the hunt for BOB. Is Gerard himself not a man between two worlds, a kind of broken conduit who only points when he is not himself and doesn’t function? And in this sense, isn’t the broken urinal perhaps a symbol for the whole of Twin Peaks?

Episode 10 begins with Cooper and Albert discovering a letter under Ronette’s fingernail, which puts her in the same conversation as Teresa Banks and Laura Palmer, but of course, Ronette isn’t dead and may or may not go on to be the American Girl Dale will encounter in The Return. The letters may be spelling Robert, but we never get all of them and they don’t occur in order, making for another synecdoche for the way in which Twin Peaks proliferates signifiers and jumbles meaning.

Of course, it is the same way with life. It may strike us as a bit unrealistic that Maddy looks almost exactly like Laura Palmer (what with both portrayed by Sheryl Lee), but this kind of resemblance between cousins is nothing fantastic to imagine. Everywhere things resonate, and so it makes sense that James sees Laura in Maddy, as does Leland…with problematic results.

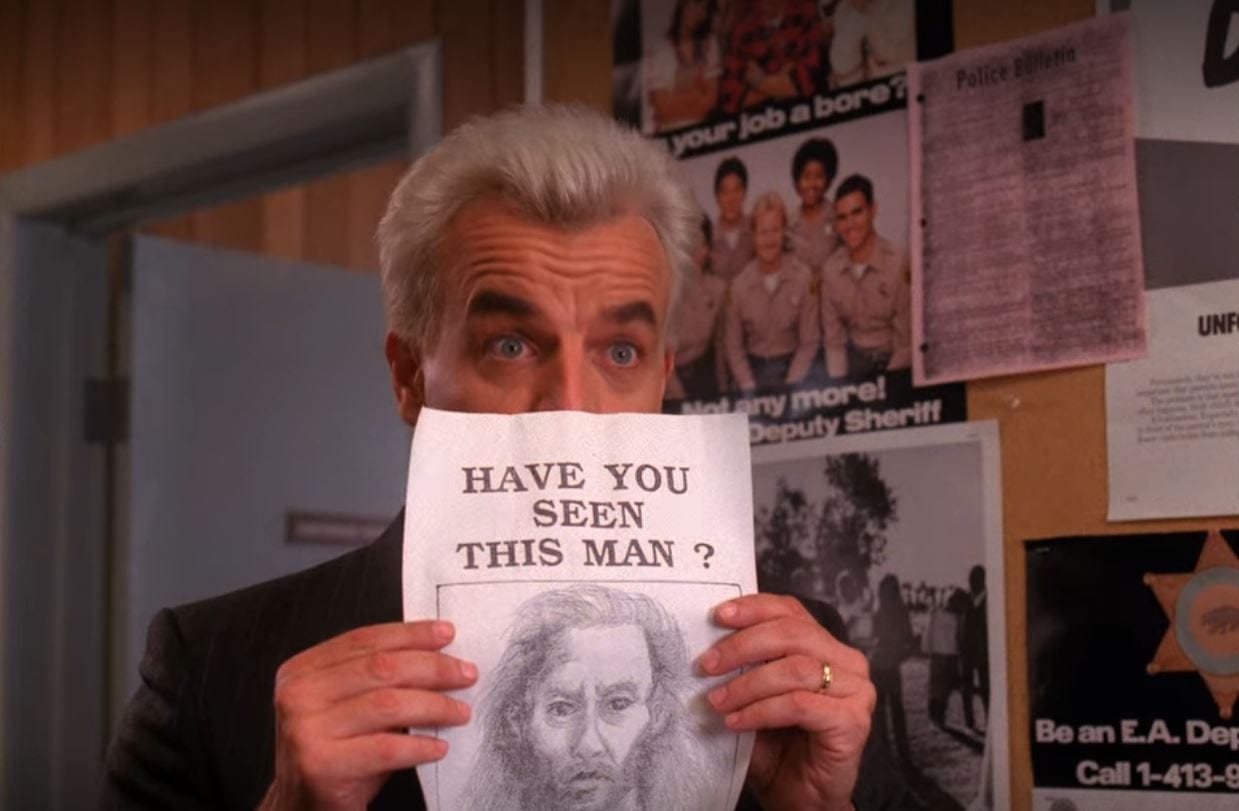

She tells Leland before he is arrested at the end of Episode 10 that she feels as though she has fallen into a dream. People treat her like she’s Laura, but she’s not. Everywhere, Twin Peaks shows us the fragility of personal identity, as it also does when Nadine awakes from her coma thinking she is 18. Leland holds up the drawing of BOB at the Sheriff’s station and says that he knows him, while we can’t help but think that we know that Leland is him. So we must be led to think that at this point Leland himself does not yet know this, an interpretation bolstered by the way he tells Laura in Fire Walk with Me that he thought she knew it was him raping her all these years. Perhaps Leland doesn’t know until he sees BOB’s face in the mirror, smiling back at him one morning—the man behind glass.

Does he hide those pages from Laura’s diary in the stall door at the Sheriff’s station? When he is arrested at the end of Episode 10, are they in his pocket? I think the police would have found them. So if he does do this, when does he do it? The Return leaves us with the rather vague suggestion that it could have been around this time, during the investigation into the death of Jacques Renault, but can we trust this, or is this like how Cooper “got the frame”? Both instances are a matter of imposing a preexisting frame of reference to make sense of a new bit of information, and of course, we do this all the time. Perhaps the inference is reliable, or perhaps we are missing something.

As he holds the drawing of BOB, Leland says that he knows him from the vacations at Pearl Lakes he took as a boy…Robertson was the name. He lived in a white house next to a vacant lot. It is easy enough to connect Robertson to BOB, though this would be not Robert but precisely Robert’s son—a detail that seems all too quickly elided as Dale jumps to conclude that the letters under the fingernails are spelling out Robert. This is not to mention the fact that they aren’t even spelling it backwards and that Cooper gets the order wrong when he says “Robert. R, T, B…that’s what the letters are trying to spell.” Teresa was T, Laura was R, Ronette is now B…Maddy will be O. Did Leland murder another girl in between Teresa and Laura, perhaps to account for the missing “E,” if this is Robert backwards? But then Ronette isn’t dead, so the inference is at once suggested and slips away. Twin Peaks gives us fragments of meaning that do not form a whole, constantly sparking tension with the mind’s tendency to want to make sense of it, where sense would precisely rely on a grasp of things in their totality.

Hegel claimed that the truth is the whole, but the Romantics knew better and found it in the fragment. But perhaps this isn’t to deny Hegel’s sentiment so much as it is to come to grips with the way that the whole always eludes us in our finitude. In Episode 10, Hawk tells Cooper that he is looking into the white house at Pearl Lakes that Leland mentioned. Can you tell me what he discovered from the title records he says he might get in the morning? Is it that the house was owned by two Chalfonts? Were the Tremonds involved? Or is it that we never hear anything further about it?

Harry will say in Episode 11 that the county records show that no one named Robertson ever owned that house. In Episode 12, Hawk hurries into the Sheriff’s station and tells Truman that he’s been talking to two retired female schoolteachers who live in the house next to the Palmers at Pearl Lakes. They have no memory of a gray-haired man, though Hawk had to drink three pots of chamomile tea to find that out. But we’re left with a fragment…because Hawk has to pee.

Great article!

Thanks David! I have also enjoyed the work you’ve done on Twin Peaks I have read, if I haven’t said so before