Twin Peaks Episode 12, four episodes down the line into Season 2, and the path toward the revelation of Leland as Laura’s killer is slowly but surely being laid. “The Orchid’s Curse” is a little bit of a stopgap, a brief moment of respite before the show really capitulates to ABC’s demands, puts its foot to the pedal, and accelerates toward the big reveal. There are no huge steps forward in plot and mythology, but it doesn’t harm the episode. “The Orchid’s Curse” works as an elaboration of the trust found in the town’s relationship; the warmth of the town toward Leland (a warmth they will sadly discover he has betrayed); Audrey’s belief in Dale Cooper as her hero; Donna’s trust in confession, with Harold her confessor; and, ultimately, the town’s belief in the human decency that can be displayed through law and justice, as compared to the cold authoritarianism such institutions often display.

It’s certainly known that to some extent the show, particularly in its first season, playfully utilises the genre conventions of the nighttime soap opera to great effect. “The Orchid’s Curse” still plays with the conventions of television, but it’s not so much the soap opera that is at play here as much as the spy/crime adventure shows of the ’70s such as Mission Impossible. As we shall see, Cooper and Truman’s “assault” on One-Eyed Jacks does not anywhere near touch the brutal, unnerving violence of The Return, nor does it even meet the queasily vicious pitch of Season 2’s most sadistic moment, the murder of Maddie. It playfully evokes the cartoon violence of a different genre and a different era, but as we shall see, the show will contrast this with emotionally charged moments that are almost meta, looping back and critiquing television’s tendency (in that era) to treat violence in a subdued, cartoonish manner, thereby neutralising and normalising it. Twin Peaks, by contrast, will not shy away from the horror of violence and the extreme emotional states that can force such cruelty to the fore.

Justice in the Court of Civic Pride

There are three main plotlines at work in “The Orchid’s Curse”: Dale’s rescue of Audrey, Donna’s submission to—and deception of—Harold, and the initial court hearings of both Leland and Leo. In hindsight, it is Leland’s hearing which will have the largest impact on the story moving forward, although we can argue the later derailment of Dale and Audrey’s relationship has a similar, if perhaps negative, impact on the latter parts of Season 2, post-revelation. But let’s put that thought to one side for the moment.

Leland is in court for his murder of Jacques Renault, to assess his suitability for bail. What is clear immediately is the idea of the town of Twin Peaks as having little in the way of serious crime. As Cooper tells Albert:

I’ve only been in Twin Peaks a short time but in that time I have seen decency, honour, and dignity. Murder is not a faceless event here. It is not a statistic to be tallied up at the end of the day. Laura Palmer’s death has affected each and every man, woman, and child because life has meaning here, every life. That’s a way of living I thought had vanished from the earth, but it hasn’t Albert, it’s right here in Twin Peaks.

This perception is also aided by the sheer overwhelming flood of emotion that pours from the town in the wake of the discovery of Laura’s body, tuned to a pitch even higher than you might expect at the murder of a beloved member of the community. This simply doesn’t happen here. Murder is a big-city problem that just didn’t apply to the small, family-friendly town of Twin Peaks.

To this end, the town does not even have its own courthouse, having to appropriate the Roadhouse, a community centre and one of the beating hearts of the town, for use in such serious legal matters when required. (Side note: If the Roadhouse really is one of the hearts of Twin Peaks, then what does The Return say about the state of it?) They even have to bring in a judge from outside, the fairminded, wonderful Clinton Sternwood, along with his law clerk, the hypnotising (to the men of the town) Sid—two of my favourite minor characters in the show.

The kangaroo court in the Roadhouse is very old fashioned, a kind of frontier setup for justice but beholden to the law of the state as opposed to the law of the land they are on. It is also quite amateurish, with the tables pushed back and rows of chairs hastily convened for an audience. The Judge presides from behind an ordinary desk, and even the bar appears to be open during a break in proceedings! Then again, having to preside over Leo Johnson might be enough to turn anyone to drink mid-hearing…

Essentially, the kangaroo court set up makes sense for a small town with little in the way of serious crime. Things have never before been so serious as to require the facilities of a full-time Courthouse. Yet there’s a problem with the idea that this setup promotes: the veneer of small-town respectability is false. The surface might be clean, but underneath, the town is infested with filth and crime of a serious nature. Not just in the sense that there are fights or adultery occurring; these occur in any small town, of course. But peel back the layers of Douglas firs and there’s Ben Horne, procuring girls for his brothel, One-Eyed Jacks, from the perfume counter of his own department store; there’s the drug trafficking with Canada that engulfs Leo, the Renaults, and Bobby; there’s Andrew Packard with extreme fraudulence, faking his own death; and there’s Ben Horne (again!) burning down the Packard Mill for the insurance money and to kill Catherine Martell into the bargain. And this is before we even get to Leland!

Like any small town, there is a mixture of people who are oblivious to what goes on in the murky depths, and there are those who choose to turn a blind eye. But ignorance or not, there is always a civic pride at the forefront, something that is always parodied when people talk about small towns. It is this civic pride, mixed admittedly with humanity, that will be the key to releasing Leland on bail, something that will have terrible consequences in just two episodes’ time.

On Bail With a Trust Misplaced

Judge Sternwood, it appears, is a fair, considerate, and reasonable man. For instance, when talking to Truman and Cooper later regarding Leo Johnson’s ability to stand trial, he asks, “What’s the temperature of the town? Do they want a trial or a lynching?” Moments later, he comments, “Well, they don’t need a circus. And this poor bastard, he seems to be a heady cabbage.” The unfortunate use of un-PC language aside, it is clear that Judge Sternwood does not see the law in simple black-and-white terms, but also with empathy and consideration not only for the community but for the alleged perpetrator, too.

We can see then how the eloquent words spoken for Leland by Sheriff Truman on behalf of the defence make such an impact on Judge Sternwood and lead him to the verdict he reaches:

Your honour, Leland Palmer is a well-known, well-liked, well-respected member of this community. His roots go way back. His grandfather, Joshua Palmer, brought the family here more than 75 years ago. Your honour, no one can know what it’s like to lose a daughter the way Leland did. That’s all.

The emphasis on displaying a sense of humanity, that Leland acted from an extreme emotional state brought on by the murder of his daughter, is clear. The argument also hinges on the lack of knowledge amongst the townsfolk of how they’d react to losing a daughter, therefore persuading them to give him the benefit of the doubt. But it is also the case that Truman builds Leland up to be a pillar of the community, the sort of person the town can be proud of. Truman even goes as far as to reference the relatively longstanding presence of the Palmer family in the town of Twin Peaks, something which should really be irrelevant when it comes to assessing someone accused of a crime. Yet Judge Sternwood, in summing up and announcing his verdict, actually refers to Leland’s place in the community and does not even mention the mitigating emotional circumstances: “On the basis of this high-standing community and the pristine nature of his public reputation and his respect for the law, the defendant is released on his own recognizance.”

In the end, it is Leland’s standing in the community and the sense of civic pride that comes with it that bails Leland out, not the more humane reason of a father in pain at the death of his child. This overinflated sense of civic pride will have awful consequences. As we‘ve established, there will always be some ignorance of untoward happenings in any small town, and the fact remains that no one outside of the Palmer family at this point is aware of Leland’s issues. Ironically, only two days after he’s released on bail, Leland brutally (and I do mean brutally) murders his niece, Madeline Ferguson. If that overinflated sense of civic pride isn’t there and Leland is held on remand, then perhaps Madeline escapes her bloody fate.

Deception for a Diary

The situation with Leland’s bail goes to prove that trust can be tenuous, depending as it might on certain conditions that we might not even be conscious we are carrying and bringing to bear on such matters. At other times, it might be that we set out to deceive from the outset, and yet we find it is only ourselves we have betrayed. This is the case with Donna when she deals with lonely shut-in Harold Smith in “The Orchid’s Curse.”

The fact that Harold has a copy of Laura’s diary and refuses to let it out of his possession hasn’t sat well with Donna in previous episodes. Why had he not taken it to the police when it emerged that Laura had been murdered? Why wouldn’t he give it to her, Laura’s best friend?

The only thing Donna can resort to, outside of outright theft, is deceit. By agreeing to become part of Harold’s living novel (“People come to me and tell me their stories about the world outside. I take their stories and place them in a larger context. A sort of living novel”), Donna is able in this episode to get Harold to allow her to read Laura’s diary.

That Harold agrees on the condition that he reads Laura’s diary to Donna, and it doesn’t leave the room, is not surprising. To a man whose world is only as big as the four walls of his apartment, the intimate thoughts and lives of other people must be such a lifeline. Not only that, his knowledge of other people and their stories is what gives him a kind of power over others. I’m not actually convinced he would read the diary to Donna. He’s uncomfortable when Donna asks questions about him—it seems to be an issue of over-idealising the world and finding that it doesn’t live up to your standards. This is perhaps where his fear of the world stems from: “I grew up in books…there’s things you can’t get anywhere…but we dream that they can be found in other people.”

Donna’s line in response (“Maybe our dreams are real”) seems to floor Harold, and she uses that space, that momentary vulnerability, to take power away from him and lead him by the diary to the outside. She playfully taunts Harold to chase her, knowing he can’t due to his agoraphobia. It’s a strange little scenario in many ways; I can understand Donna not trusting Harold. He didn’t take Laura’s diary to the police after she died, which is unlawful if nothing else. But there is something slightly cruel about the way she teases him, a smile on her face, knowing his weakness is being exploited.

Yet Donna hasn’t bargained on the importance of Laura’s diary to Harold. So, despite his agoraphobia, he bursts out of his apartment’s front door after Donna, only to realise what he has done and collapse in sheer panic and anxiety, clasping the diary to his heart. At this, Donna shows some genuine concern and care, cradling Harold’s head in her hands. She realises that there have been unforeseen consequences to her actions, to her abuse of Harold’s trust. She certainly hadn’t intended to hurt anyone. In fact, this moment of vulnerability seems to endear Harold to Donna more. When talking with Maddy later, Donna admits that she likes Harold and, if there’s nothing incriminating in Laura’s diary, she will still see him because she “likes him a lot.” Clearly, Harold has awoken something in Donna that she did not expect. While this doesn’t stop her from still deceiving him—“If there’s nothing in that diary we’ll give it back to him, but we have to know”—it has compromised her deceit, tempered it with unexpected affection. As we shall see, this will have some unexpected consequences for both Donna and Harold.

The Secret of Knowing Who Killed You

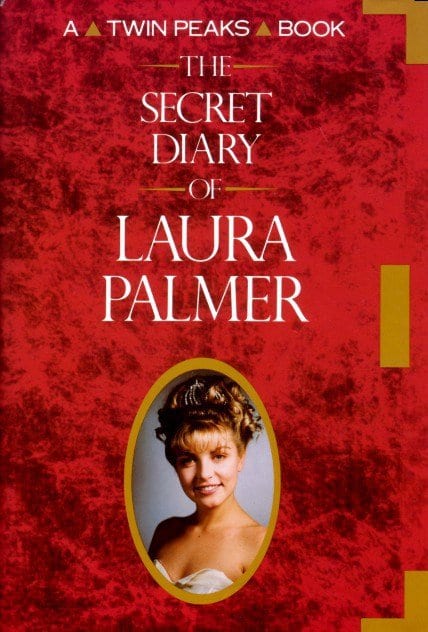

This time when they meet, with Maddy watching from the shadows, waiting for a signal to swoop in and snatch the diary, Donna acquiesces to Harold’s need for secrets and confession. She begins to tell him a tale of teenage sexual awakening, one that would have been very familiar to those fans who read The Secret Diary of Laura Palmer prior to the airing of Season 2. The story Donna tells is lifted straight from those pages, based as it is on the story Laura told in her diary of meeting three older boys, Josh, Rick, and Tim, at The Bookhouse (although it’s changed to The Roadhouse in the episode) and going with them to a stream in the woods.

What’s fascinating about this is that most shows with tie-in books take their information from the show but rarely feed back into the universe of the show itself. It goes to show the quality of The Secret Diary and the worth Frost and Lynch felt the diary had in expanding the universe of the show that they allowed this story to make its way back into the show and become canon (Barry Pullman wrote the episode, but Mark Frost had the last pass at any script produced and would have been aware of the story appearing previously in The Secret Diary). There’s no doubt to The Secret Diary’s place in the Twin Peaks canon now, but back then it must have seemed a really fresh thing to do. There’s also a meta aspect to this, as Donna is relating this story from The Secret Diary with the aim of reclaiming the diary itself from Harold.

By submitting to Harold’s compromise and confession, Donna submits to a part of herself that she has perhaps been too afraid of in the past to embrace. In the Season 2 premiere, we see Donna embrace her inner Laura, adopting a poor impression of what she thinks was Laura’s cool—sunglasses, cigarettes, and talk full of attitude. Here she uses memories of a previous intimate experience—being kissed by Tim in the water, and the sensuality of that experience—to unconsciously, naturally, access this part of herself. She seems to fall into a semi-trance, standing up and acting the moment out with small, gentle movements. From Laura’s perspective, Donna’s idea of sensuality and sexuality was childish, insipid, but it also didn’t help Donna that she was aware of Laura’s magnetism to others and felt she couldn’t compete. Here, in the act of confession to Harold, she allows herself to be who she truly is without fear of judgement.

This leads us to another way of looking at this: Perhaps, despite the story being told to Harold to titillate, tantalize, and distract him, it quickly becomes a quiet, sensual exorcism. Donna is simultaneously trying to reclaim her friend by embodying her through memory and pushing the memory out of her by performing it. Ultimately, the exorcism fails. Laura never leaves Twin Peaks (or is allowed to, as we see by the end of The Return). It also betrays Donna’s more innocent sensuality (“that was the first time I fell in love”) and why her attempts to embody Laura are doomed to fail—she ultimately isn’t Laura. The cigarette ash falls to the floor like the discarded emotions she has released. Donna looks emotionally spent by the end of it.

Certainly, if we take the first interpretation, it’s a beautiful moment and resolves itself in a kiss with Harold, one too passionate to be deception and yet one which aids Donna in her plan. Harold excuses himself in a flustered state, allowing Donna to signal Maddy to work out the secret shelf hiding Laura’s diary. Alas, Harold comes back before Maddy can finish the job, and the mood quickly changes as he realises the truth. He picks up a three-pronged gardening fork and corners Maddy and Donna in the corner, his voice alternately gruff, commanding, and fragile, whilst the skewed camera angle he is framed in only emphasises the sinister snap in his thinking: “Are you looking for secrets? Is that what this is all about? Well, maybe I can help you. Do you know what the ultimate secret is? Do you want to know what Laura did? The secret of knowing who killed you.”

At this Harold drags the rake horribly down his face, the blood oozing from the cuts as his eyes stare wildly out in a frightened, righteous trance while the girls scream at the horror—and it is certainly like something out of a horror film, the act of unexpected self-mutilation forcing questions of what Harold might do to the girls if he is willing to do such things to himself.

Again, we have a scenario where trust has been misplaced, with severe consequences. Here, we are left on a cliffhanger, with Harold having raked his own face. What will he do next? The key, of course, is in his last utterance here: “The secret of knowing who killed you.” As we’ll see in the following episode, Harold takes his own life. Donna’s awakening in him of the possibility of genuine love, and then the betrayal of that intense feeling with her deceit, has left him to feel like she’s forced his hand. It’s one betrayal too far for him. He ultimately puts the blame for his death, whether rightly or wrongly, at Donna’s feet.

Meanwhile, for Donna, what starts as simple deception becomes a source of finding new trust in herself. She taps into a side of herself that she had repressed and actively becomes attracted to the man she is deceiving. It was never going to last, and sadly it doesn’t.

Mission Impossible: The Twin Peaks Edition

It’s interesting that the last episode I took a deep dive into, “May The Giant Be With You,” ends with the Giant pointing out that Coop is missing something, alluding to Audrey’s letter under Coop’s bed, and that this episode opens up with Coop doing a headstand for yogic healing and noticing Audrey’s letter under the bed. But that’s a coincidence for me to worry about, not you.

The retrieval of this letter taps quickly into Cooper’s guilt at failing another woman he cares about. Dale Cooper’s White Knight syndrome is well established, and Audrey is certainly not immune to its consequences. The fact that the letter has been under his bed all that time undoubtedly eats at Cooper. It’s lost time, and if Audrey gets seriously hurt or even killed during that period, I can imagine Cooper would never forgive himself.

As mentioned earlier, there is a shift in generic conventions when Cooper and Sheriff Truman embark on their mission to rescue Audrey from One-Eyed Jacks, Cooper sneaking up to One-Eyed Jack’s in his black stealth clothes (Truman, ever the country boy, opts for jeans instead). Now, contrary to The Return and the general body of Lynch’s work, and in line with the likes of family-friendly shows like The Man From U.N.C.L.E. and The Avengers, the violence here takes a turn for the silly, as Truman incapacitates the bouncer with a grab of the genitals, a gag in the mouth, and tape for silencing before banging said bouncer’s head into the door. Smashing a man’s face to a bloody pulp after arm wrestling, this is not.

In fact, what is curious is that the violence throughout this sequence is never excessive. Yes, Jean stabs Blackie, but even then it’s quite tastefully done—Blackie’s body is held close to Jean, and you don’t particularly see the knife penetrate her. There’s also an exchange of gunfire between Renault and Truman reminiscent of any cop show you care to name of that time. Even the rescue of Cooper and Truman by a stealthy Hawk, who achieves this by throwing a hunting knife in the back of an armed bouncer, is done with gentle good humour (“Good thing you guys can’t keep a secret”). Coop’s and Truman’s smiling shakes of the head could have come straight out of an episode of Happy Days or something (yes, I know Happy Days is not a spy show!)

It’s interesting how the tone changes when Cooper finds himself emotionally charged. Upon seeing Audrey in her drugged-up state on the bed, his mood shifts. Moments before, Coop had disarmed Nancy using only a handshake into an arm twist. Now, as Nancy tries to talk her way out of any trouble, Cooper snaps at her to “shut up” and disarms her approach with a knife by punching her with real aggression in the stomach. The shift is palpable, and it really sticks out on any rewatches. This, more than anything, truly puts across the love Cooper has for Audrey. It’s been talked about many times how one of the plans for the continuation of the story was to focus on a relationship between Cooper and Audrey. The reasons this didn’t come to fruition have been told many times, and I won’t dredge them up here. But needless to say, the scene here demonstrates that such a storyline really could have worked, producing as it did such strong emotions from both story and actors.

It also forms a commentary on TV violence of the time as well. Rather than arguing for and against the depiction of violence, it instead depicts TV violence as it was seen by most people of the time and then places it against scenes of emotionally charged moments, such as Coop’s sighting of Audrey and Harold’s realisation that he’s been deceived, so as to show that this depiction of violence, when coupled with really dramatic and emotional impetus, can be effective. It seems quite quaint to argue this point now when TV violence is perhaps at the other end of the spectrum, but the argument for such violence when relevant to the dramatic peaks of a story is fascinating in the context of the times.

Finally, can I just say that in an episode where the main theme is how misplaced trust can have dire consequences, it does warm the heart to see Audrey’s trust in Cooper justified. Her prince comes after all and rescues her. And although she never wins his heart, she’ll always have that.

Conclusion

“The Orchid’s Curse” might feel insubstantial when you watch it. It doesn’t make any big points per se, and it doesn’t push the mythology forward. However, what became clear to me on this rewatch is that the theme of misplaced trust and the subsequent consequences form a core that is actually in line with the rest of the series. By the season’s end, Coop will find that his trust in his own courage was deeply misplaced, with exceptionally severe results. Audrey’s trust that she can make a difference will end in an explosion in a bank (not her fault, admittedly), and even Windom Earle’s trust in his ability and right to take Cooper’s soul proves to be nothing but hubris.

Viewed through this lens, Twin Peaks Episode 12 provides a microcosm of one of the show’s main themes, but not necessarily one that is talked about often. It’s an episode that’s richer than it first appears, full of hope and tragedy. Soon, the hope will be quashed. But for a moment, for characters like Cooper and Audrey, it feels at least like there are options.