Animation has long been one of my favorite film mediums. Great artists tell fantastic stories through colorful lenses of exaggerated colors in dazzling, surreal landscapes. When it’s done well, it’s magic, and when it’s not so well, it remains imaginative. I knew Death Does Not Exist (La mort n’existe pas) would be a challenging film. Félix Dufour-Laperrière leads us to the edge of a precipice from which there is no return—a look into an abyss that stares right back. There’s no going back once you start a fight. One way or another, somebody’s got to finish it. Dufour-Lapperrière casts an animated stone in the name of revolution, then has the gall to ask if we’re sure it’s what we want?

When a group of teenage activists makes plans to execute the head of an affluent family, the question becomes whether or not they’ll be able to do it when the time comes. The answer to that question comes during the moment for Hélène (Zeneb Blanchet), who freezes at the edge of a large estate where she watches as her friends’ attempt to infiltrate the grounds goes sideways, all because she wasn’t there to do her part when the time came. From here, Death Does Not Exist becomes an existential tome, adjacent to the conversation and monologuing found in Linklater’s Waking Life, but with a more pointed dogmatic undercurrent about the Circle of Life.

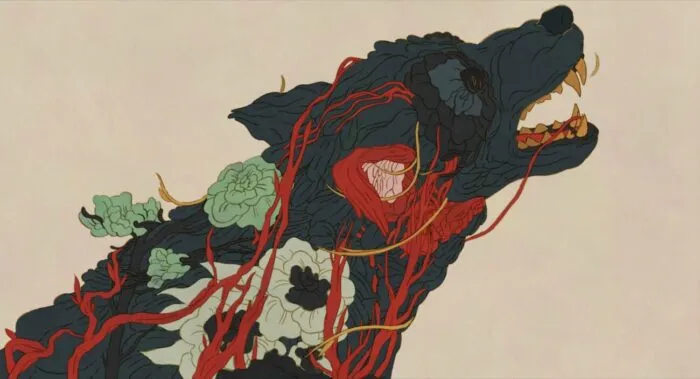

The animation in the film is unique, if only because of the opacity of its creatures and characters, which move atop textured canvas paintings layered beneath the roving artistry. This odd contrast allows humans to blend in with nature, but never as bright or colorful as the inherent natural aspects of the design. The creatures seem less opaque, suggesting a better relationship with nature. To say the animation is gorgeous doesn’t do Death Does Not Exist enough justice; this is animation that needs to be beheld.

However, while its animation is deeply enriching, Death Does Not Exist’s story is a bit like having a one-sided interview where all the questions are known in advance and you can softball them right back to yourself. The topic is revolution, and the question subtextually echoing throughout the forest is, when does hurling rhetoric change into hurling bricks, i.e., when should we consider violence an option? The film is seen through the eyes of youthful inexperience, naïve beliefs, and endless political frustration, the kind that allows for billionaires to continue causing irrevocable harm to the planet.

Hélène talks a good game, pitching the violence like she sees it all the time, but a disappointed look in the eyes of their target causes her hesitation. After the event, her friend Manon (Karelle Tremblay) calls her out for her cowardice, but tells her she has a second chance to go back and complete her part, as guards from the estate descend upon them and chase them through the woods.

The animation changes throughout their time in the woods, providing a similar effect to how the sun changes the appearance of a forest throughout the day. During this time, Manon kills a rabbit for the two to eat in the woods without even giving a second thought to the necessity of it. And symbolically, there’s a sentiment here about the nature of humans taking what they want, discarding things where they choose, and calling it survival. The bunny will feed the two this evening, but that won’t stop another bunny from being chosen the next night. When will the bunnies say they’ve had enough, or will they disappear entirely from the forest?

The film portrays nature as a violent and chaotic world governed by primitive rules, and it heavily advocates for the utilization of our caveman instincts before offering some reprieve in the final act. Manon’s principles follow Hélène as she seeks clarity. The experience feels akin to going to a place in your head and reliving a moment with new perspectives over the years, and yet, there are a few philosophies it doesn’t account for. Martyrdom, for example. Yet it quickly changes tune from a “You Say You Want a Revolution” vibe to an “All You Need Is Love” affair, through just a touch of An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge.

While antagonistic, Death Does Not Exist is smart in how it presents its appeals for violence through animation: war, drought, melting polar ice caps, fascism. There is a sea of reasons worth revolting against. On occasion, leaving convoluted and contradictory beliefs hanging against one another works well, allowing shades of gray to produce thoughtful examination. However, I often felt there was more to glean from certain debates, with consequences never at the forefront of these ideas, which harkens back to this plot being driven by youthful ignorance.

All in all, Death Does Not Exist is a lovingly rich feast of color that provides a sensory element to Hélène’s journey, as does the film’s incredibly mesmerizing film score by composer Jean L’Appeau. By which there are many entrancing moments. However, throughout the film, How to Blow Up a Pipeline continually invaded my thoughts. How to Blow Up a Pipeline is another film that calls for similar impulsive actions in the pursuit of eco-justice. Still, I think it’s a little smarter in pushing its characters into individual corners for relatability and motivation.

Yet, there’s still something about this movie. I know I’ll want to return to Death Does Not Exist in a few years to see if I see it a little differently than how I see it now. Perhaps when the doomsday clock strikes one second to til midnight and the end is nigh, wondering if we all missed the revolution.

Death Does Not Exist played at the 2025 Fantasia International Film Festival on Thursday, July 17. Check out the film’s page on the Fantasia website for more information.

Teaser trailer for Death Does Not Exist

Teaser trailer for animation Death Does Not Exist, directed by Félix Dufour-Laperrière, which screened in Cannes and will feature at Annecy.