The Theology of the “Woo”

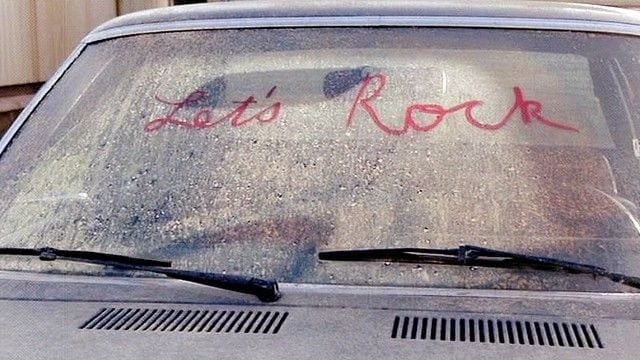

In Almost Famous, there’s a scene backstage before a Stillwater concert where Russell Hammond (Billy Crudup)—eyes bright, guitar in hand—attempts to articulate the essence of rock & roll. He’s being interviewed by William Miller (Patrick Fugit), our teenage protagonist, on assignment for Rolling Stone. They’re chatting in a dressing room, chaotic and alive with pre-show energy. Amid the swirl of activity, Russell rambles, tunes, riffs—and then reaches for something deeper.

He’s groping for “The Indefinable Thing”—try to explain that inexpressible spark when someone truly feels your music. “The thing you put into it,” he begins, before trailing off: “I’m talking about…what am I talking about?” Shyly, William interjects: “The buzz?” Russell instantly lights up: “The BUZZ!” he exclaims, seizing on a word that, at least momentarily, seems to capture what was just ineffable. The “buzz” is the thing that makes it all worth it. The fame, money, and women are just offshoots and distractions. The real force in music is that flicker of connection between a song and the soul it reaches: “The voice that says here I am… and F*CK YOU if you can’t understand me.”

Trying to define “the buzz” with pinpoint poignancy, Russell lands on a perfect example: Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On.” However, instead of celebrating the timeless groove and melody, he fixates on an offhand “woo” at the end of the second verse. He celebrates this “woo” as an errant, unguarded, unwritten snippet of emotional spontaneity slipping out. It’s expression in its purest form. “That’s what you remember,” Russell exclaims. “The silly things. The little things.” The most bona fide musical paroxysms exist not in what you mean to play, but in what escapes when you forget you are playing. “It’s not what you put in,” Russell says. “It’s what you leave out. That’s rock & Roll!”

Chasing the “Woo”: Ad Hoc Sincerity as Crowe’s Auteur Legacy

For Cameron Crowe, this stray “woo”—the unexpected burst of emergent, unpremeditated authenticity—is everything. It’s the human residue that outlives the performative guise; the tremor of sincerity that survives jaded ossification; the innermost ebulliance that outshines the false sheen of social peacocking and propriety. Regardless of the setting, Crowe chases after such moments: searching for the raw glimpses of unvarnished humanity seeping through the cracks; capturing those rare, elevated moments that reveal the soul.

From Say Anything to Almost Famous, Jerry Maguire to Vanilla Sky, and Elizabethtown to Aloha, he explores the ethical tensions between individuated scrupulousness and commercial compromise, the sociological rifts between interpersonal steadfastness and capitalist pandering. His films may be digestible and mainstream in sentiment, but they thematically thrive in that off-script space, documenting the thin line between appearance and essence, public image and private truth.

Throughout his oeuvre, authenticity functions as more than a theme—it’s the spiritual fulcrum of his entire filmography. Regardless of his chosen milieu—the tour bus, the zoo, a sports agency, a lucid dream—he diligently charts how sincerity collides with ambition, belief is tested by failure, and rectitude must be continually re-earned. His characters fumble, bomb, and flop, sometimes spectacularly, but they still triumph simply by taking the difficult detours—professionally and privately—that make life worth the journey.

Film after film, Crowe lauds the surviving idealists amongst us: those determined souls who, despite being surrounded by a culture of compromise and concession, desperately attempt to forge something real in systems engineered to peddle falsities. His protagonists—writers, agents, designers, dreamers, zookeepers—universally find the temerity to navigate untidy imbroglios, tackle impediments head-on, and confront the gripping existential doubts we all feel deep down.

Almost Famous: The Iconography of the Uncool

Authenticity operates on multiple tiers in Almost Famous, his most autobiographical and layered work. It applies to musical, journalistic, personal, and emotional stakes. Set in the early 1970s, the film follows the aforementioned 15-year-old William Miller as he chases his dream of becoming a rock journalist by shadowing a popular band on tour. What begins as the opportunity of a lifetime gradually becomes a personal crucible as William is forced to maneuver around minefields of fame and friendship without sacrificing his journalistic rigor.

Stillwater, the fictional band he’s profiling, wants to be (somewhat paradoxically) perceived as both cool and legitimate. Stardom and the grind of the road have slowly chipped away at their innocence and grassroots sensibilities. The lead guitarist, Russell Hammond, purposefully crafts an impenetrable mystique while drifting further into ego and excess. Jeff Bebe, the frontman, resents being eclipsed. And the band collectively pressures William to sanitize his article to preserve their iconography. The film’s central tension lies in this predicament: Can William find the guts to prioritize probity when everyone around him is pushing a narrative?

In the hands of Crowe’s Academy Award-winning screenplay, William’s rite of passage incisively exposes the contradictions of the rock-and-roll mythology. “Adolescence is a marketing tool,” growls Lester Bangs (Philip Seymour Hoffman) in an all-time rant over the telephone. Lester functions in the film as a mentor figure to William and an ostensible stand-in for Crowe’s proselytizing impulses. “The day it ceases to be dumb is the day it ceases to be real,” he continues, preaching on the nefarious seductions within rockstar culture: “They make you feel cool. But you’re not cool […] the only true currency in this bankrupt world is what you share with someone when you’re uncool.” These words anchor the film’s philosophical thesis. More often than not, being “real” isn’t debonair, rad, or chic. It’s gawky, lonely, and terminally unsexy. Yet, when everything is said and done, it’s the only thing that matters.

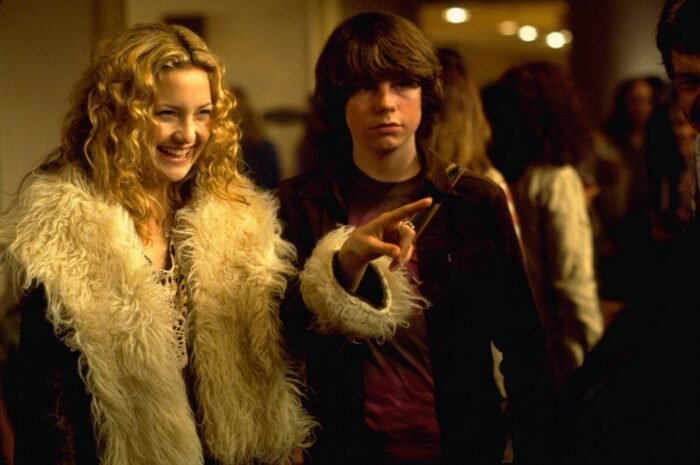

Penny Lane: The Person Beneath the Persona

This same sincerity runs through Penny Lane (Kate Hudson), the band’s ethereal and wounded muse. At first, Penny appears to embody freedom and mystique: she’s the ultimate Band-Aid, not a “groupie,” exactly, but someone who “inspires the music” and lives just outside the boundaries of conventional life. On an external level, she presents a glamorous image of herself—rootless, ethereal, invulnerable. Her existence is a painstakingly sculpted and maintained façade—she has no fixed age, a self-appointed surname, no known history, and supposedly zero emotional baggage.

Sadly, however, as the tour continues, holes in her outward act and imperturbable put-ons appear. Her deep (unreciprocated) love for Russell—a glaring narcissist—exposes her emotional fragility. When Russell trades her to another band “for fifty bucks and a case of beer,” the fantasy she’d scaffolded collapses. She overdoses on Quaaludes and ends up with her stomach pumped in a hotel room—a sharp, jarring contrast to her earlier glow.

In this way, Penny doubles as the film’s martyr. She wants to float above the jaded cynicism of her environment, yet she slowly becomes a casualty. She cautiously constructs a discreetly enigmatic persona—complete with an alias and a flighty hippie attitude—to survive in a world that treats women as disposable, yet she remains defenseless beneath her semblances of detachment. And although she evades transparency (posturing and hiding her true identity to imbue herself with the entrancing lure of ambiguity), she stalwartly maintains the courage to feel and care in a world that punishes warmth, confidentiality, and attachment. That means something.

In this way, Penny becomes one of Crowe’s most tragic, complex characters and one of his most deeply human, if not cynical, portrayals. Over the arc of the film, her magic dissipates. After she’s abandoned and disillusioned, the mask crumbles, and her refusal to forfeit her underlying emotional investment in genuine human connection becomes apparent. Fortunately, she doesn’t remain broken, entirely. William, who sees Penny as more than the persona she flaunts, helps her slowly recognize her self-worth again. When she reveals her real name before departing to Morocco, it is a potent gesture of rare frankness in a world built on aliases and self-mythologizing.

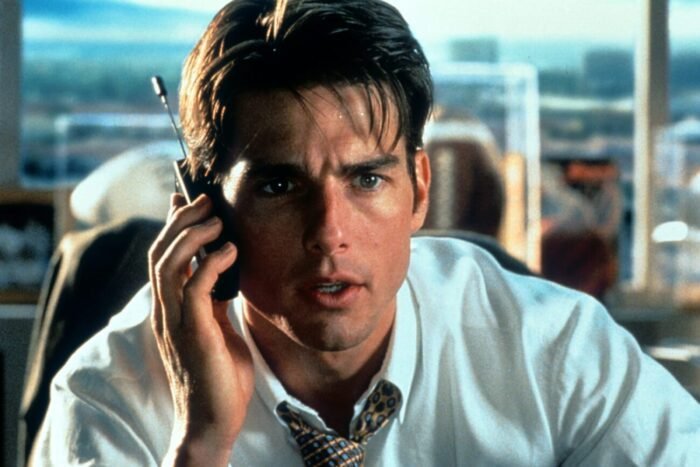

Show Me Your Vulnerability: Jerry Maguire’s Core Mission Statement

The layered character portraits in Almost Famous serve as a Rosetta Stone for Crowe’s canon and creed. The film’s poignant exploration of what it means to be real—in music, love, journalism, and one’s artistic calling—echoes across his other works, where authenticity is similarly fragile, hard-won, mercurial, and transformative. Jerry Maguire, arguably Crowe’s most commercially successful film, similarly follows a renegade ingenue: the titular sports agent who pens a passionate industry critique after a late-night crisis of conscience.

Spurred on by a breakthrough of impulsive righteousness, Jerry brazenly challenges the mercenary values of his profession, embracing a more human-centered model of doing business—one grounded in fewer clients, deeper relationships, and emotional transparency. (This fictional epiphany is so integral to Crowe’s worldview that he wrote a full metatextual “Mission Statement” titled The Things We Think and Do Not Say: The Future of Our Business. Even today, almost 30 years after Jerry Maguire’s theatrical release, the impassioned manifesto still lives on Crowe’s website, The Uncool, as both a character backstory and an ideological exegesis.)

Unfortunately, Jerry’s call for reform fails to turn him into a folk hero around the office; instead, it swiftly costs him his job. A series of professional losses, emotional reckonings, and slow-burning rebirths follows as Jerry learns that living by upstanding values comes at a price—even if this price is a mandatory toll one must pay before achieving genuine self-fulfillment. With edifying clarity, Crowe uses his mid-life professional crisis not to condemn ambition but to recalibrate and redefine its merits.

After Jerry is fired, he vehemently invites his colleagues and clients to join him in forging a more principled path forward. What’s left in the aftermath is minimal but meaningful: one client, one assistant, and one chance to do things differently. Rod Tidwell (Cuba Gooding Jr.), the lone athlete who sticks with Jerry (an infamously volatile NFL wide receiver), becomes part of the film’s conscience, demanding loyalty and transparency in return. Tidwell challenges Jerry to care, commit, and show up not just as an agent, but as a person. In doing so, he demands the values Jerry claims to believe in, thereby testing whether his zealous principles can survive the grind of reality.

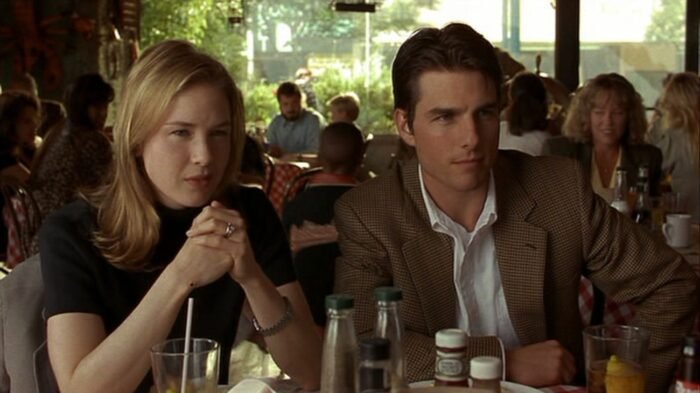

Dorothy’s Unheralded Resolve and Bravery In Love & Business

Meanwhile, Dorothy Boyd (Renée Zellweger) is the only colleague moved enough by Jerry’s plea to follow him out of the office. While others giggle, wince, and quietly quail from his meltdown, she recognizes something honorable in his quixotic vulnerability. “I think in this age, optimism like that… It’s a revolutionary act,” she compliments. What draws Dorothy in isn’t just romantic potential (though that thread is present), but shared conviction. She admires Jerry’s integrity—flawed, idealistic, slightly naïve, but refreshingly artless. And so she quits her stable job not (solely) for a man, but for a vision: a more intimate, ethical way of doing things.

In this sense, Dorothy is a romantic in work and life, drawn to decency and intimacy, even when the outcome is uncertain; like Jerry, she is willing to stake everything on the hope that uprightness and sincerity still matter. However, Dorothy’s quiet devotion is as unnerving to Jerry as it is reassuring. Late in the film, after exposing her messy personal life to Jerry after falling in love with him, she asks him not to dazzle her, but to really love her. The ultimatum is telling. For Dorothy, love isn’t cemented by sweeping romantic gestures (even if “You complete me” is one of the great romcom lines of the last 50 years). It exists in mutual loyalty, inexhaustible solicitude, and human genuineness in the face of overwhelming odds.

In this vein, true success in romance and the sports business in Jerry Maguire transcends contractual obligations and flashiness (even if the film is known for the iconic “Show me the money!” scene). It is solidified by showing up with honest intentions, heartfelt ambitions, and no guarantee that things will work out. Sports (with its relentless churn, transactional rosters, and unforgiving scoreboards) and marriage (with its emotional undertows and interpersonal obstacles) become backdrops for a far more uncertain yet dignified pursuit: building a life on trust, faith, and fidelity. In the end, Jerry Maguire is about enduring when things get hard; it’s about the humble, daily decision to live with conviction, regardless of expected rewards or results.

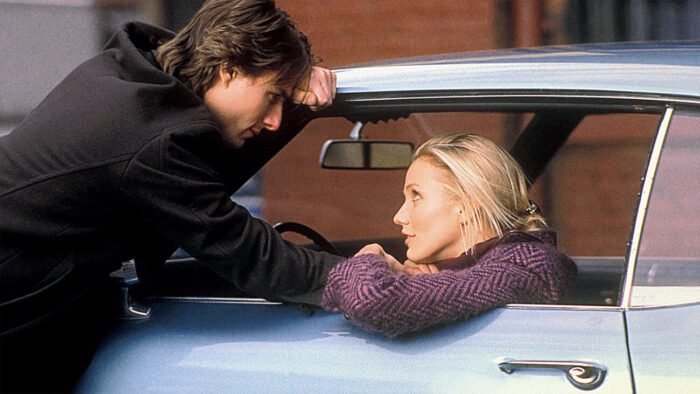

Say Anything: The Grace of Emotional Naiveté

These same themes take another form in Say Anything, where dishonesty is tied not to romance but to financial and parental/familial betrayal. In the film, Diane Court’s (Ione Skye) father, Jim (John Mahoney), is indicted by the IRS for embezzling money from a retirement home, effectively dismantling Diane’s idealism. In stark contrast to this downfall, Lloyd Dobler (John Cusack), Diane’s love interest, emerges as the embodiment of an honest, emotionally forthright connection—he’s awkward, spontaneous, yet stripped of disemblance.

Jim and Lloyd represent conflicting value systems: the pillar of traditional success vs. the novice with zero societal prestige or conventional prospects. Crowe pits these foils (two polar opposite archetypes of masculinity) against each other to question the inverted morality of the modern age. Jim’s betrayal isn’t just legal—it’s emotional, paternal, psychological, and metaphysical. It strikes at something foundational: the mythology of responsible adulthood. The man who taught Diane to value excellence and to chase after scholarships and structure is revealed as someone who mendaciously conned the system, exploiting others and imperiling his family’s security for unearned gains.

On the other hand, Lloyd exists outside that system of wealth and fiscal shadiness entirely. He has no long-term plan, salaried trajectory, or explicit interests in orthodox affluence. What he does have is a radical kind of sincerity. When Diane breaks up with him under her father’s influence, he doesn’t retaliate or retreat—he simply (and oh so cinematically) stands in the rain, tape deck over his head, playing Peter Gabriel’s 1986 hit “In Your Eyes.” What could be read as a cliché feels earned because it’s the culmination of a character who has never hidden his feelings. His vulnerability—sometimes ungainly, sometimes clumsy—gives Diane a moral ballast in a world of murky rationalizations and unconscionable schemes.

The juxtaposed men in Diane’s life remap what credibility and reputability look like. In a world where fiscal competence can mask profound amorality, Crowe champions honesty and dependability as deeper, more radical forms of nobility. Ultimately, trust isn’t something accessed by money—it’s something modeled by the maladroit young man who refuses to lie, even when it would be easier, more acceptable, or more “grown up” to do so. Here, Crowe suggests real adulthood is not about monetary accumulation or control, but about relinquishing perfidy and replacing it with emotional openness.

Elizabethtown: From Footwear to Soul Repair

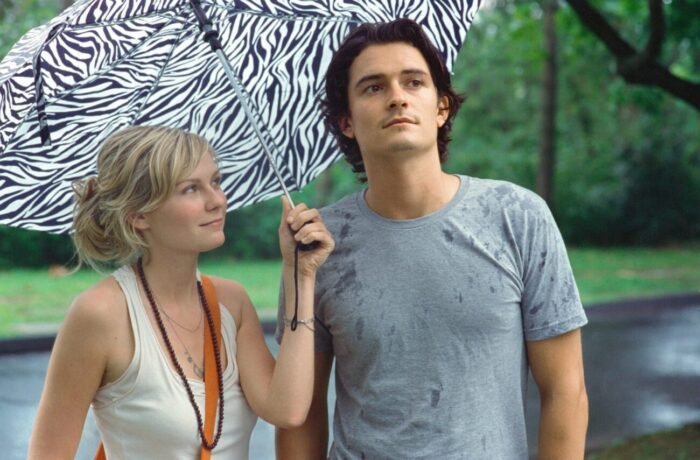

In Elizabethtown, Drew Baylor (Orlando Bloom) thrives in a world of pretense. When we meet him, he’s consumed by corporate ambition—so much so that when a design flaw in his shoe costs the company nearly a billion dollars, he spirals into suicidal despair. His world feels hollow, defined by profit margins and stock prices. Then, a cascade of unexpected moments—losing his job, losing his girlfriend, and meeting Claire Colburn (Kirsten Dunst)—pulls him back from the edge. Claire’s warmth may flirt with the manic pixie dream girl trope, but her presence steers Drew toward something deeper.

What unfolds within Drew is a steady reawakening via small, human gestures. Claire’s quirky charm and emotional intelligence reintroduce him to a softer, more reflective, and ultimately, romantic, brand of existence. Their extended late-night phone call, stretching into the early morning, serves as a spiritual cleanse. Sure, the conversation is rife with the fluttering butterflies of nascent courtship. But on a deeper level, it simultaneously shows Drew a different way of being: a world of emotional richness and intimacy outside of the high-stakes titillations and corporate diversions of pathological careerism.

Once again, Crowe’s chief protagonist becomes a cipher: another lost soul on a symbolic journey of spiritual reincarnation. Drew’s emotional rehabilitation is pointed, indicting corporate psychology as soul-eroding by contrasting it with the power of elemental human relations. For Drew, vindication and clarity aren’t found in another pitch deck or high-profile shoe launch—they’re actualized in embracing vulnerability: in tears shed with family, in laughter shared at a roadside attraction, in the catharsis of heartfelt romance.

By film’s end, Drew’s confrontation with the finality of death (symbolized by the panicked regret of cremating his father and his subsequent decision, upon Claire’s behest, to take a road trip to spread the remains) illuminates what truly matters in life. And when he decides to prematurely pause his road trip to find “the girl in the red hat” (i.e., Claire), the rediscovery of a genuine relationship feels earned—proof that pain, and the nearness of mortality, can illuminate a path toward individual enlightenment.

Vanilla Sky: A Surrealistic Search for True Happiness

Vanilla Sky, a loose remake of Alejandro Amenabar’s Abre Los Ojos, (a Spanish film that also stars Penelope Cruz), introduces similar existential quandaries, albeit with much greater layers of abstraction: exploring the dangers of curated identity and artificial happiness inside a phantasmagoric terrain. The plot revolves around David Aames (Tom Cruise), a media heir who enjoys an idyllic lifestyle of sex, power, and aesthetic perfection. But after a car accident disfigures his face and disrupts his life, reality collapses into a sci-fi-tinged psychological labyrinth.

David’s road to recovery devolves into a surreal, nightmarish journey. He is placed in cryonic suspension, entering a surrealistic sub-reality created by the Life Extension program. The goal of this program is to induce a state of lucid dreaming so as to occupy the mind until a medical solution can be reached. An inadvertent side effect is that the liminal, psychological zone forces David to confront the truth of his existence. As he drifts through looping corridors, distorted reflections, and uncanny conversations that feel familiar and alien, the film zeroes in on the hazards of living life as a carefully polished product rather than a holistic reality filled with organic, meaningful relationships.

The question “What is happiness to you?” lingers at the film’s heart. It is first asked by Julianna Gianni (Penelope Cruz) moments before the crash that derails David’s life. Initially, the question comes across as a deceptively simple moment of vulnerability tucked inside a jealous romantic exchange. In Julianna’s mouth, the inquiry doesn’t feel abstract or theoretical; it’s emotionally loaded. She’s hurt, searching for meaning in their “fuck-buddy” relationship, trying to understand why she feels so disposable.

In the moment, David deflects, as he’s prone to doing. But the question lingers—not because he answers it, but because he doesn’t. It becomes a thematic seed that blossoms as David’s dream world begins to fracture his former lifestyle, tying into the film’s critique of pursuing illusory happiness via avoidant sensory pleasures. It compels David to investigate his myopic life choices, the nature of reality, and what truly matters beyond the vapid signifiers he’d previously worshipped. It offers no easy answers but insists that authentic experience—even pain—is superior to simulated bliss.

The line (“What is happiness to you?”) also reappears in Vanilla Sky‘s final, climactic moment—this time not as a romantic provocation, but as a poignant existential interrogation. After navigating a dream world designed to anesthetize pain, David stands on the precipice of self-reckoning. With the dream world dissolving and Ventura (the Tech Support) reverberating Julianna’s question, he unguardedly replies: “I want to live a real life. I don’t want to dream any longer.” From a man who previously micromanaged every aspect of his personality, the answer is plainspoken, direct, and unembellished.

Seconds later, David enters a vertiginous free fall back into lived experience. As he leaps, the screen floods with a rapid-fire montage. Notably, the images do not depict wealth, sex, or fame. Instead, they feature tactile, quotidian, uncurated slivers from his memory—a glance from a stranger, his mother’s face, scenes of laughter, quietude, and intimacy. The screenplay describes these images as “the little things, the random poetic instances of David Aames’ life.” The phrasing is no accident. It reflects Crowe’s recurring fascination with life’s authentic moments—with the small nuggets of truth that break through the noise (much like the “woo”) and resonate by reminding us we are alive.

Aloha: Reconnecting in a Disconnected World

Aloha (2015) attempts to probe the tension between manufactured power systems and organic cultural identity, albeit imperfectly. The film positions the military-industrial complex—personified by Bradley Cooper’s Brian Gilcrest and Bill Murray’s megalomaniacal billionaire Carson Welch—against the spiritual and ecological sanctity of Hawaii. The satellite launch behind Gilcrest’s contracted assignment in Oahu symbolizes this tension, spotlighting the ethical consequences of pursuing technological progress untethered from communal and environmental considerations.

Once complicit in the corrosive machinery of modern society, Gilcrest finds himself increasingly disoriented in a landscape where everything—the land, the people, even the mythology—insists on connection, continuity, and reverence. Surrounded by ghosts from his past and immersed in a spiritually rich culture, he slowly begins to reckon with his moral and spiritual compromises, realizing how ambition alienated him from community, purpose, and love.

Crowe uses this moral dilemma to contrast the cold, coded language of military objectives with the organic fluency of Hawaiian culture: blessing rituals, oral histories, and deep-rooted cosmology. While the film sometimes stumbles into cultural gaffes and taboos of its own (it was critiqued for whitewashing Hawaii and misappropriating the island’s patois), its intentions are redeeming insofar as it keenly suggests that true progress cannot come at the expense of history, culture, and ecosystems.

In this context, Aloha becomes a meditation on reestablishing a sense of rootedness in land, memory, ancestry, and eternal, earthly forces. Gilcrest’s atonement hinges on his willingness to listen rather than lead, dismantle rather than execute, and trade colonialist aspirations for realignment with something older and wiser than himself. It’s a flawed film, yes. But it is also a fascinating study into how modernity’s sleek promises often pale beside the eternal truth of the earth spinning beneath our feet.

Even We Bought A Zoo: The Power of 20 Seconds

Then there’s We Bought a Zoo (2011). Occasionally dismissed as excessively middlebrow, maudlin, and saccharine, this film nonetheless reflects Crowe’s enduring belief in risky, heartfelt self-reinvention. Its setup is simple, following Benjamin Mee (Matt Damon), a grieving widower who purchases a dilapidated zoo to reconnect with his children and rebuild their lives. Of course, the project is healing. Of course, it serves as a metaphor for courageous self-renewal. Of course, Crowe’s formulaic premise pays off by dint of his rousing, unabashed sentimentality. But sometimes feel-good movies work despite their familiarity.

In one of the film’s most pivotal and powerful scenes, Benjamin brings his children to the cafe where he first met their late mother. As they sit at a table by the window, he begins to recount the moment he saw years earlier and drops a wallop of tear-jerking sagacity: “Sometimes all you need is 20 seconds of insane courage, just literally 20 seconds of embarrassing bravery, and I promise you something great will come of it.” The quote has manifold layers. Most literally, it’s the origin story of Benjamin’s family—had he not mustered the nerve to speak to his future wife, their children might never have existed. As advice, it’s broadly applicable, reinforcing Crowe’s recurring insistence that self-actualization often awaits on the other side of transitory apprehensions.

On a personal level, reliving the memory of meeting his wife brings Benjamin back to the beginning. Retelling the story, he turns the aphoristic “20 seconds” pep talk into a recursive truth. The callback attests to his steely heart, resilient spirit, and revived fortitude. He’s fully ready to rebuild after the loss of the family’s dear, beloved mother figure. The leap of faith may have changed, but the overarching principles have stayed the same: he may no longer be preoccupied with asking someone on a date, but he still needs the bravery and courage to fight doubt and keep grief at bay long enough to heal and grow, both as a man and a widowed father.

Thus, the oft-quoted line doubles as a heartwarming moment of paternal encouragement and a distillation of Crowe’s doctrine. In a world where tentative prudence and protective wariness reign supreme, Crowe repeatedly extols the opposite: impulsive sincerity, emotional risk, and the quiet heroism of complete vulnerability. For Crowe, a minuscule window—a mere twenty seconds—is all it takes to ask someone out, quit the wrong job, or tell the truth. Winning is not actualized in money, touchdowns, or shoe designs. It manifests in the infinitesimal, split-second choices where pluckiness and verity override duplicity and trepidation. It manifests in moments that may seem small in isolation, yet in the grand scheme, serve as the ruptures where true transformation begins.

Cameron Crowe’s Proudly Unhip Moral Tenor: Earnestness as a Revolutionary Vocation

Ultimately, Cameron Crowe’s cinema realizes moral sanctimony does not exist unimpeded, nor does ethical purity ever sync with the easy decision. Acts of goodness are messy and perilous: the hard-fought corollary of striving for truth in a world of disingenuousness. If he has left an indelible mark as a sweepingly sentimental auteur, it lies in his ardent-hearted belief that the struggle for authenticity—however bumbled and bungling—is noble in itself. In this way, he remains one of our last true romantics, steadfastly championing the genuinely flawed, the serially uncool.

His characters are a rare breed that write manifestos, forfeit salaries, and believe mixtapes have eternally therapeutic properties. They are the type of people who boldly confront mid-life stagnancy and declare a personal war on the vapidity of corporate culture (whether it be rock & roll journalism, sports business, shoe designing, media publishing, military enterprises, or zookeeping). They are the brave souls who still dare to attempt to articulate and/or actualize something candid and guileless, no matter how insane, idealized, or impossible the task may seem.

Often, his protagonists fail. This doesn’t matter because for Crowe, authenticity isn’t about perfection. It’s about tapping into what’s still present when the social airs and affectations of identity break down. It’s about capturing the “woo” of unrehearsed emotion—the impromptu moment when someone forgets they are being recorded and remembers they are alive.

Stuck within a postmodern milieu that prizes arch detachment and snarky irony, Crowe remains defiantly and wholeheartedly earnest. His unapologetically tender works personify a kind of emotional populism, where meaning is measured not by sophistication or prestige, but by humanism and resonance. Without any chagrin, he fervidly reassures audiences that small moments can carry epic weight, and that ordinary people—flawed, frazzled, blunderingly sincere—can be granted mythic dignity simply for caring in a world that coerces us not to. And that’s a legitimately winsome agenda: an aspiration that one might argue is worthy of “wooing.”