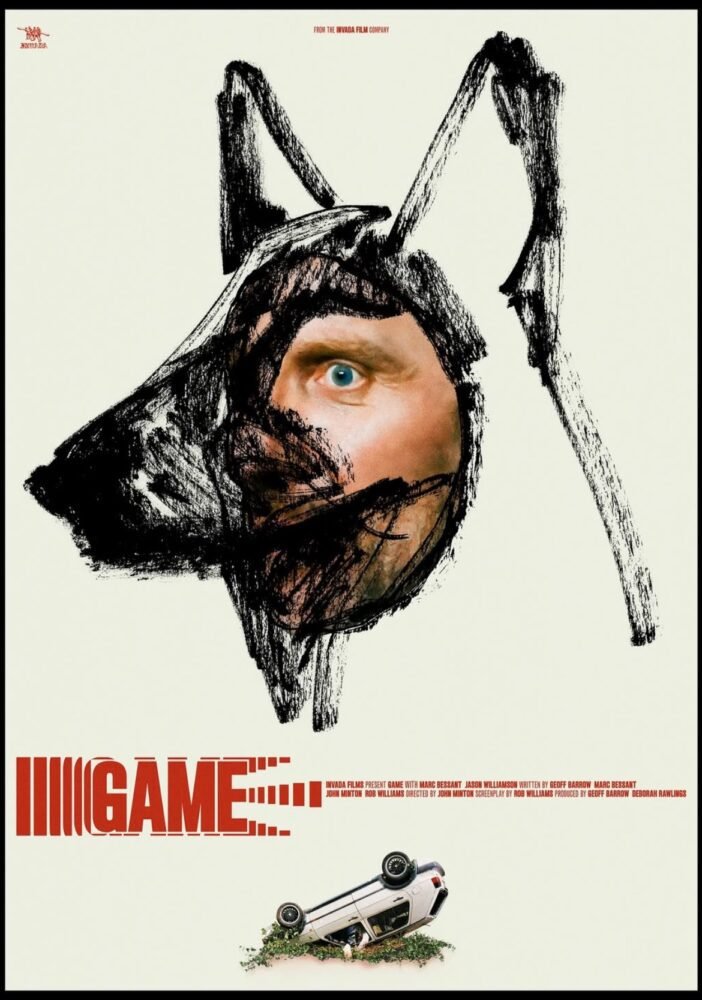

What happens when a BAFTA-winning editor swaps shorts for a no-distributor rave nightmare? I saw the answer when watching Game at Mayhem Film Festival a few weeks ago, and now I had the chance to find out from the director himself, John Minton.

My teenager, Fern, had loved the film too, and couldn’t help gatecrashing right at the start: “It would have been better if it was called Flippy Car, they said, “or Trippy Car”; and you’ll understand why (on both counts) when you see the film. I was ready for a more sensible conversation, but Fern didn’t want to step away: “Well, why did you call it Game, then?”

John was thankfully endeared towards this direction: “Look up ‘game’ in the thesaurus,” he said, “and it will give you multiple very good reasons why it’s called Game.” I had assumed it had to do with the predatory nature of the film’s dynamic.

“Initially, it was called The Poacher,” John went on, “but I had issues with that, because the poacher doesn’t turn up until halfway through the film. Having flagged that we needed another name, our writer Rob [Rob G Williams, one of four people with co-writing credits] had like three possible names ready off the top of his head, and Game just stood out to me. I looked it up: you have the connotations of playing a game, it’s used in a game of soldiers, and all sorts of things.

I even took a screen grab of a thesaurus, played with it in Photoshop just to show all the reasons why the name made sense. Our initial response was ‘a four-letter word, game, is that it?’ Also, because we’re based in Bristol, we have close links to Cornwall and Mark Jenkin’s Bait; I know him and the producers, and we almost collaborated on something once, and our record label Invada Records produced the Bait soundtrack.

So initially, it felt like the title Game was too close to Bait; these are the kind of thoughts you have, but it never came up at all until we were previewing the film in the summer at Watershed in Bristol, just for ourselves, and Mark Cosgrove, who runs Watershed, mistakenly called our film Bait as we were walking in.”

Great film to be mistaken for, mind you!

The mention of collaboration brought me to a question. Game emerged from conversations among collaborators who’ve worked in music, visual art, and genre storytelling. I asked John as director, how he shaped contributions from Geoff Barrow, Marc Bessant, and Rob Williams into a unified vision, especially given the friendship dynamic behind the project.

“It happened in stages,” John said. “Initially, it was just four guys down the pub who talked about doing this thing, and there were many years leading up to even that. Even when Geoff had called me initially in 2021, perhaps, he and I had already talked about a project, telling a story, possibly based on Ballard’s book Concrete Island, which I’ve never finished yet; something achievable about an isolated circumstance in one location, ideally.

So from there, the four of us just forged ahead. I was very daunted about being the director of this: I’d directed plenty of music videos and edited maybe ten short films over the years, and looked after bigger things like massive tours; so I knew I had the skills to be a director, but to actually be the person responsible for bringing the story we were developing to screen… that filled me with fear.

Our budget was low, and we were doing it ourselves, but we had friendship behind us. And we’d collaborated on plenty of other projects before, especially me and Geoff; Portishead being the massive one for me. Outside of Portishead, there were smaller things we did together too, often just stepping in to help each other out.

Marc had always been there with us; he used to design Portishead’s sleeves. Then I appeared on the scene around 2005, got involved with the label first, and then with Portishead. Rob was someone I met through Geoff, partly to do with a script he’d written, but also we play football together; we have this famous Monday night team called Brian Munich, been going on twenty years!

“So we’ve got a real bond between us, and this really is a collaborative project. We’re supportive of each other and value each other’s creative input; sometimes Geoff and Marc are like brothers, they’ve known each other since school. Receiving everyone’s input and trying to incorporate everything is something I’m kind of used to doing, working with artists and bands, multiple voices and clients, labels on one hand and bands on the other: in the music world, you have to work that way.”

I had assumed that moving from the music world to film would be a change of mindset. “No, I’ve been drawing on a lot of skills learned elsewhere and applying them to this project,” John confirmed. “This would be a new environment and our skills were going to be tested, but we kind of had a gut feeling that this would still be a creative project like any other.

The biggest thing here is storytelling: we’re serving the story, rather than serving the music or an artist or something along those lines. The story almost becomes the client, but we were making the story. I studied graphic design, and I’ll always think back to having a brief: I’m always happy with being set a brief and working out how to meet it.

With Game, we were setting our own brief, and then a scene is a microcosm of that brief. Then once we had the story, it was about delivering that, and the tone was always up for discussion.

Geoff and I would talk a lot – even at football on a Monday night – we’d talk on the phone, get together and carry on the conversation, then feed it back to the other guys and work it out as a group, round in circles, and Rob would go back and write. Once we had that, we had to work out how to deliver on the budget we had and in the time we could afford.”

The tone must have been tricky to agree on. Game’s style combined that of a thriller with some almost pastoral, almost meditative woodland elements. I asked John what had attracted him to that contrast.

“I guess in the script, the forest elements were a lot more characterful,” John said. “I don’t mean pagan folk type stuff, but it definitely had a lot more description of the forest breathing and reacting to the intrusion of the car and so on.

Then in the act of trying to deliver that, it wasn’t part of our schedule to shoot those things, we just couldn’t afford to include it in the schedule: we delivered everything, completed every day, and then there was this list of other stuff that was down to me to get. But I never really got it. We did a couple of pick-ups.

I went out with my mate Ross, the DOP [Ross James, director of photography], we shot some extra stuff, and eventually I was just drawing that stuff from test shoots or these days when I was there with a camera and Ross was shooting something else.

Eventually, I just had enough material, but it was all simply shooting the environment as it was: you know, I need ‘this’, or I need several cutaways without repeating myself too much. Then bringing the animals in was all stock footage, apart from the pheasant near the beginning.”

I really liked that opening; it was both lovely and tense, watching the pheasant being stalked. John expanded: “Weirdly, I went out on two occasions to shoot pheasants – with a camera, obviously – and both failed. I was feeling a bit at a loss; I mean how do you get pheasants, who are famously camouflaged and hard to shoot, this is a BBC Wildlife level of shooting; and then Sam [Sam Morgan Moore], our camera operator/gaffer/grip, was caring for his Mum, and she has a home that back onto an estate where pheasants pop over the fence into their garden to pick up food.

So he just started filming them through the cut flap there in the garden, managed to get the shots; he knew the storyboard and what I needed. I managed to cut that in with another test shoot of my friend dressed as a poacher mooching through the woods; I’d assumed we would need to reshoot those, but we never did. That has happened a lot in my career: make something expecting to do it again sometime, but find the one we had worked.”

Perhaps opportunistic filmmaking like that contributed to the unusual genre blend, I suggested: psychological horror, character drama, and, of course, thriller. I asked John what he had expected audiences to take away from that. “We knew we wanted the woodland to be quiet,” he said. “Through the sound design process, which was quite late, we were peeling stuff away. We didn’t want any classic tropes of horror or spookiness: we felt the silence was spooky enough. So we wanted the audience to feel tense, without telling them to feel that way: we were going to be in that environment for a long time, after all.

Even at the end of the film, when you’ve got the trip, we didn’t want to be conventional in the sense of distorting the imagery. I mean I’ve made a lot of psychedelic, analogue, feedbacky material for music in my career, and we could have gone down that route of distorting the visuals and things being quite wild.

This was something Geoff and I talked about early on (I’ve learned to listen to Geoff’s gut instincts): that the trip itself was going to be the scene with most clarity in the film, flipping conceptions of how things should be. Perhaps the guy in the car is tripping, haemorrhaging in his mind; I even did some tests where I was distorting the footage in the car, but they didn’t sit quite well. I could tell that immediately. We were trying to tell a story, and exist in a cinematic world, so it was worthwhile trying to avoid low-budget tropes of trying to do something that was just candy, I suppose.”

As a result, most of the film was naturalistic, and therefore very plausible, I thought.

“Yes, it was all about that,” John agreed. “And we try to apply that in music too: we want it to be as it is.”

Talking about music, I asked John about working with fellows from the music industry in the film. “I was born in ’77,” John said, “and was fairly sheltered in ’93, when the film was set: I was into my parents’ ‘60s record collection, full of guitar music, classics. So my experience was much more Oasis, Charlatans, indie pop. Then, of course, Portishead and The Prodigy were important to me: I was much more mainstream than rave.

Whereas Geoff and Mark are a little bit older than me, they were in that scene, had a real nuanced understanding of where rave was at in ’93: it had gone through its early years and was in a more commercial environment. Actually, Geoff and Ben Salisbury have been scoring films for some years – and some really good ones – very successfully, and Geoff didn’t want this to be a vehicle for his score.

I edited without temp music, we didn’t have temp music, and I didn’t want Geoff to have that old battle with a director (which he’s had on occasions) where you’re writing as a composer, but you’re fighting with the temp music in the film, battling for position with sound effects, sound designers, all that.

So all the rave music in the film was stuff that we commissioned from a mate of ours who we play football with, Jamie Paton, he wrote a lot and we started using those in the edit when we cut away from the car. Geoff would remix or mess around with those and then as and when the film needed music, Geoff and Ben would write something which Geoff didn’t necessarily want to put his name to, but it was serving the film.

As for Bolero: there was always going to be a piece of music for the trip scene, and as far as we were concerned, that was it: some rave music and that trip. But then the film kind of demanded some more: there was a kitchen scene, for example, and we had to think of what would be playing in the background there, so he wrote something for that.

And the structure of the film demanded some more music; we had a dream sequence, you know, that bit with the dog, which needed another piece of music.

I made something temporary for that and then sorted out a better piece. I knew we needed something dreamy: I’d found some ’93 house stuff from YouTube, picked one which turned out to be Laurent Garnier, who had just been to one of Geoff’s gigs; I asked we could use it, but he wrote something special.

That was the only time we used temp music, really, and it gave Geoff the problem of writing his music to fit. Then there was another piece that leads into leads into the trip… so I guess it sounds like there was a score, but really it grew from a place of having no score.”

It definitely sounded like useful music scene insights, rather than baggage. “Absolutely,” John agreed. “And I think it was quite fun. Throughout the project, Geoff enjoyed nailing the period, choosing the music, really having an opinion about what would be worn, and so on.

You see nineties social scenes being reimagined on film and my wife has this hobby of kind of identifying when things are out of place, saying ‘they would never have worn that,’ and whatever. That’s something we really leant into, making sure there was authenticity, as far as we could.”

Game is now on a tour of independent cinemas around the UK, having held its world premiere at Mayhem Film Festival and been presented at some other UK festivals after that. “We’re kind of treading water now, between the premier and these other screenings, waiting to see if the press picks it up at all, coming up with little promotional ideas. Then we’ll see what happens.”

I can imagine the press might not know how to tackle it. My nearest independent cinema is The Mockingbird on the edge of Birmingham city centre; I asked John if I encouraged my friends to go and see Game there, how would he suggest I describe the film. “I’d say it’s a psychological thriller with a battle of wits between two characters, and yes, it does genre-hop. Sometimes I find myself describing it as if you can hang in past the first half hour, you’ll be rewarded. We put a lot of effort into that first half hour, too, in pre-production, production, shooting; it was the most complex element, and the rest of it just flowed.”

Fern had another contribution: I bet you had to hope it didn’t rain then, too.

“Oh man, yes,” said John. “We were so lucky: we had a heatwave during that shoot. Actually, I really enjoyed your question at the premier,” he continued, and again, it’s not my interview now. “You asked me about the trip, about how we did the visual effects. And it bamboozled me at the time because I was thinking ‘what effects?’ and I took it as a compliment, because as an editor, I cut a lot of stuff hoping to manipulate or induce a feeling from cutting images. So in that sequence, the only effects we had used were manipulating colour really, and juxtaposing images with each other.”

I find it quite interesting that the forest suddenly presents as a church, or a battle scene, to show us the characters’ frame of mind. “That was the bit I was most looking forward to making,” said John. “In the edit, the cut you see is the first cut I did: it just worked, but that was kind of disappointing, because I wanted to work on it a lot more. What ground me down was the earlier parts, getting the pacing to flow right.”

Fern had a teen-worthy description of the film to offer, too: like a medieval duel, but instead of swords and shields, it featured intellect and drugs. “That’s a good shout,” said John, “I’ll take that. The route of a lot of thinking is about two worlds colliding: one, an older man, and one modern. There is certainly some subtext there which we left subtle, but could have pushed more. Ultimately, it is about two people, one wanting to get out of a situation and the other already in a situation with his whole life and not really wanting to help; both their buttons are being pushed.”

Catch Game at the cinema if you can, or join the mailing list for news of home release.