It’s hard to overstate the lengths to which Twin Peaks fans will go to when analyzing the things seen and heard in this show. But, as Dale Cooper himself said, “When two separate events occur simultaneously pertaining to the same object of inquiry we must always pay strict attention.” So it was with particular curiosity that my ears perked up when references to the famous Arthurian legends began appearing in The Return. In conversation with my 25 Years Later colleague Eileen, we’ve hit on the idea that Agent Cooper appears to be on a Hero’s Journey, and more specific to that, a kind of Grail Quest, both of which have deep roots in English literature (and, indeed, around the world.)

To begin, let’s look at the criteria necessary for one’s journey to qualify as a hero’s journey. American mythologist Joseph Campbell lists seventeen steps in the exposition of the monomyth. Reading through this list brings to mind great heroes of the literary canon, from Beowulf and Gilgamesh to Frodo Baggins and Lisbeth Salander. We can (and should) add Agent Cooper to this list, as many of these criteria are met by his journey both in Seasons 1 and 2 of Twin Peaks and now within The Return:

- The Call to Adventure (“She’s dead, wrapped in plastic.”): This brings the hero to a place of natural wonder (“Got to find out what kind of trees these are, they’re really something!”) or into an intense dream state. Campbell says that this place is one of “strangely fluid and polymorphous beings, unimaginable torments, super human deeds, and impossible delight.” Sounds a lot like our Twin Peaks, doesn’t it?

- Refusal of the Call: “Refusal of the summons converts the adventure into its negative,” Campbell writes. Cooper certainly experiences this midway through Season 1, as the investigation hits walls and Cooper’s enthusiasm is met with skepticism.

- Supernatural Aid: “For those who have not refused the call, the first encounter of the hero journey is with a protective figure (often a little old crone or old man) who provides the adventurer with amulets against the dragon forces he is about to pass.” The Giant/Room Service Waiter Dale meets in the Season 2 opener would seem to tick all of these boxes with ease.

- Crossing the First Threshold: “With the personifications of his destiny to guide and aid him, the hero goes forward in his adventure until he comes to the ‘threshold guardian’ at the entrance to the zone of magnified power,” Campbell says. “The question is: where have you gone?” the Giant—a clear and obvious threshold guardian—asks Dale.

- Belly of the Whale: The hero is tested. (“I will tell you three things.”) He must pass these tests, but may face setbacks as well. This is the case with Dale throughout the first part of Season 2.

- The Road of Trials: Here, the hero “must survive a succession of trials.” The game with Windom Earle and the several mini investigations of Season 2 prepare Cooper for this showdown, as do his search for the answers to the clues the Giant gave him, which do lead him to the identity of Laura’s killer.

- Meeting with the Goddess: Of this, Campbell writes that “The meeting with the goddess (who is incarnate in every woman) is the final test of the talent of the hero to win the boon of love (charity: amor fati), which is life itself enjoyed as the encasement of eternity.”

- Woman as Temptress: The hero faces temptations, which may cause him to stray from his quest. The Goddess and Temptress figure seem to both be represented by Annie Blackburn.

- Atonement with the Father: At this point, the hero must confront the thing that wields most power in his life. In Dale’s case, this seems to be the resigned realization Dale experiences over his inevitable confrontation with Windom Earle.

- Apotheosis: At this point, greater understanding is achieved and the most dangerous part of the journey is undertaken. This would appear to be the moment when Dale crosses the threshold into the Red Room.

We are, it seems, hovering around point 10 in Campbell’s list: Cooper has been stranded in the Red Room for a quarter century, and though it appears he has left the room, there is still a long way to go before he receives any kind of reward for his trials. The remaining seven steps—The Ultimate Boon (The achievement of the quest); Refusal of the Return (hero’s unwillingness to return from this place); The Magic Flight (The hero needs to make a daring escape with the boon to avoid capture by the gods); Rescue From Without (Someone from outside of his journey steps in to help him achieve his ultimate goal); The Crossing of the Return Threshold (The hero must figure out how to share his gained wisdom with the rest of the world); Master of Two Worlds (the Hero finds a balance between material and spiritual, good and evil, inner and outer worlds); and Freedom to Live (free from the fear of death, the hero learns to live in the moment)—have not, as of yet, all come to pass. We are left to speculate about the ultimate goal of his journey truly is. It could be his freedom. It could be Laura Palmer. It could be his working intellect. Time will (maybe) tell, but at this point, we have nothing but speculation. But Cooper’s Hero’s Journey is far from over.

As a subset of the Hero’s Journey, Grail Quests also live in a particularly mythic corner of literature. Grail Quests have their origins adjacent to the Arthurian legends, with one of the first recognized instances being recorded in Chrétien de Troyes’ Perceval ou Le conte du Graal from 1190. In this story, and most of the Arthurian legends that followed it, the grail is literally depicted as a cup or chalice that was used to collect the blood of Christ at the crucifixion. The quest represents a search for something that has the power to sustain life, but which is obviously very hard to obtain. Usually the quest takes the questing knight through a barren, inhospitable wasteland to the home of the Grail (usually a castle) guarded by an old, ailing owner (usually known as the Fisher King). When it is found, the questing knight becomes the new guardian of the Grail, replacing the Fisher King and restoring power to the kingdom. On a literal level, it is a quest for a thing, but on a deeper metaphorical level, this is a quest for something different.

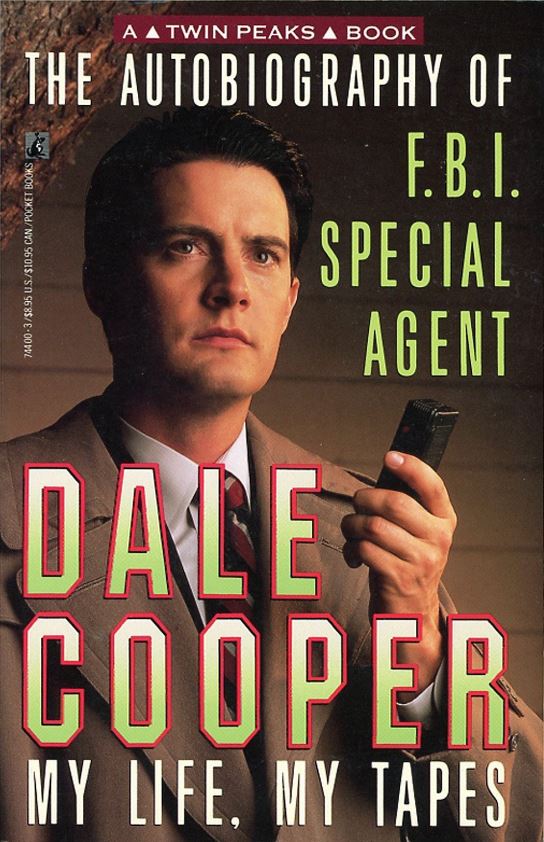

Obviously Agent Cooper isn’t questing for the Holy Grail as we know it from the Christian and Arthurian traditions. His grail is of this second metaphorical kind—is he on a quest for perfection, perhaps? a quest to find himself?—and perhaps he has been on it for quite some time. Based on his autobiography (My Life My Tapes, or MLMT), from early childhood Dale has been searching for his place in this world, his purpose. His journeys seem to take him on the kinds of adventures that most young boys in 1960s America went on—Scouting trips and camping with family and into the orbits of the beautiful and intriguing women he meets along the way—and it leads him to discover his aptitude for crime-solving, which eventually leads him into the FBI. He doesn’t appear to achieve his Grail by the end of the book, which is where Twin Peaks begins and Cooper’s quest continues.

Obviously Agent Cooper isn’t questing for the Holy Grail as we know it from the Christian and Arthurian traditions. His grail is of this second metaphorical kind—is he on a quest for perfection, perhaps? a quest to find himself?—and perhaps he has been on it for quite some time. Based on his autobiography (My Life My Tapes, or MLMT), from early childhood Dale has been searching for his place in this world, his purpose. His journeys seem to take him on the kinds of adventures that most young boys in 1960s America went on—Scouting trips and camping with family and into the orbits of the beautiful and intriguing women he meets along the way—and it leads him to discover his aptitude for crime-solving, which eventually leads him into the FBI. He doesn’t appear to achieve his Grail by the end of the book, which is where Twin Peaks begins and Cooper’s quest continues.

The first explicit Arthurian mentions in Twin Peaks go back to the final episode of Season 2, in which Glastonbury Grove (alternately spelled Glastonberry in some Twin Peaks reference points) is first named by Sheriff Truman as the possible location where Windom Earle has taken Annie. Glastonbury is, as Cooper points out, the mythical resting place of King Arthur. It is linked to the Isle of Avalon, which is the land beyond where Arthur lies waiting for when Britain needs him again and he can return to his people. That a Glastonbury Grove exists in Twin Peaks is not in itself remarkable, but it is noteworthy that this Glastonbury links to another “land beyond”—the Red Room, or the Black Lodge, is only accessible from this location at certain times. Cooper is drawn into this place by Windom Earle, using Annie as bait, and a part of him doesn’t return. (Well, not for a quarter century, anyway.)

At the end of Season 2, when the Arthurian references begin in earnest, it seems as though the Grail Dale is searching for is tied to Windom Earle and the Black Lodges.1 Cooper chases Windom and Annie into the Lodge in an attempt to rescue her, and finds himself coming face to face with his doppelganger and the evil that lives in the woods, while his faithful companions stand watch outside.2

Eventually, however, “Dale” reemerges, although it is made clear right away that the real Dale is trapped in the Lodge/Red Room. As we pick up with his story in The Return twenty-five years later, Dale is only now permitted to leave and return to life outside.

When Dale appears to exit the Lodge and return to this mortal coil, we find him inhabiting the life of a man named Dougie, who resides with his wife and son in a Las Vegas neighbourhood known as Lancelot Court. Within Lancelot Court, presumably, the street names are all taken from the Arthurian legends; we only hear of a park at the corner of Guinevere and Merlin in Part 6, but it’s hardly a stretch to assume that the naming convention extends to the rest of the subdivision (especially with dozens of places and character names remaining within the Arthurian canon.)

Added to the earlier mention of Glastonbury in Twin Peaks, it becomes apparent that a theme is running here. What are we to make of this deliberate choice to imbue the world of Twin Peaks with so many references to the legend of King Arthur? The two couldn’t be further apart—geographically, anyway—but thematically there might be more to this.

From here, Cooper continues his journey occupying the space left by Dougie Jones, who appears to be a facsimile of Cooper intended to capture his soul as he left the Lodge rather than replacing DoppelCooper as intended. Here, it seems there is another kind of quest going on: that of Cooper returning to his former, brilliant, FBI self. Six hours into The Return, it’s unclear when—if ever—Cooper will come back to himself, but the journey he’s on at the moment could certainly be paralleled to a kind of Grail quest: with Dougie-Cooper cast as the knight, travelling through the arid landscape of the Nevada desert, searching for himself, at which point his power will be reasserted and he will reclaim his place in the world.

One other thought that occurred to me (with many thanks to my colleague Eileen) was that perhaps Cooper, rather than being cast as Percival, the Grail Questing knight, is actually being cast as Arthur himself. Arthur is said to be resting in the Isle of Avalon (accessed through his burial place in Glastonbury) until the time when his kingdom needs him again. Cooper is trapped behind the veil at Glastonbury Grove, and the land he’s left behind has largely fallen to pieces. We see and hear anecdotal evidence of the decay that’s now no longer lingering beneath the surface of the town of Twin Peaks but present on the surface. The town presents a grittier feel, more of a piece with other modern towns in America, rather than being sweetly idyllic. There is a war raging, and at least two residents of Twin Peaks have seen active combat, with ripple effects from their injuries being felt by several people around them. Agent Cooper’s return could be the very thing that sets this place, beloved by him and us in equal measure, back to rights. As Arthur may some day need to return to his people, Cooper—it seems—needs to return to Twin Peaks.

If nothing else, perhaps Agent Cooper himself views his role as something akin to the great King Arthur. Published in 1958, when Dale was but a toddler, the ragingly popular “The Once and Future King” by T.H. White was a fantasy novel about the young Arthur that almost certainly would have nestled on his bookshelf next to weighty tomes on fingerprint analysis, Scouting manuals, and a dogeared copy of the biography of J. Edgar Hoover. It is perhaps bad form to quote from Wikipedia, but as a description of both the plot of the novel and of the future Agent Cooper’s life, it is particularly apt: “As the young Arthur becomes king, he attempts to quell the prevalent “might makes right” attitude with his idea of chivalry, even as he foresees the ascendancy of another form of might, namely legal prowess in the courtroom, and, from without, a form of fascism.”

great King Arthur. Published in 1958, when Dale was but a toddler, the ragingly popular “The Once and Future King” by T.H. White was a fantasy novel about the young Arthur that almost certainly would have nestled on his bookshelf next to weighty tomes on fingerprint analysis, Scouting manuals, and a dogeared copy of the biography of J. Edgar Hoover. It is perhaps bad form to quote from Wikipedia, but as a description of both the plot of the novel and of the future Agent Cooper’s life, it is particularly apt: “As the young Arthur becomes king, he attempts to quell the prevalent “might makes right” attitude with his idea of chivalry, even as he foresees the ascendancy of another form of might, namely legal prowess in the courtroom, and, from without, a form of fascism.”

Sounds to me like someone we all know and love very much…

1 A postmodern literary take on the Grail Quest describes a villain attempting to steal the Grail for their own nefarious purposes. If the Grail is knowledge of the Lodges or the power to control them, could Windom Earle have also been on a Grail Quest of his own?

2 (In an unused portion of the S2 finale script, Sheriff Truman sees an arm reach out from the red curtains clutching a sword; the Arthuriana nut in me went a bit wild with the thought that this was a reference to Excalibur)

***Edit (June 17, 2017): An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that Cooper was “inhabiting the body” of Dougie Jones. This has been corrected to reflect that it is physically Dale Cooper in the Las Vegas scenes, and that he is only living Dougie’s life, not that he is existing within Dougie’s body.