When I was 17 years old, I found myself in what I would consider to be my own personal equivalent to the Black Lodge: a 48-hour hospital stay following a suicide attempt at the end of my senior year. School had been a miserable time, as I imagine it is for most children who fall under the great wide umbrella of “non-neurotypical,” and inadvertently blowing up a friendship/possible relationship wound up being the straw that broke the camel’s back.

I could probably still tell you just about every detail of the space I occupied for 48 hours of my life. The dull white walls, illuminated by harsh neon lights. The relentless itch of the hospital clothes we were given. The overwhelming sense of shame, not only at the need to get permission to do something as simple as going to the bathroom, but that I had somehow failed myself and the people who cared deeply about me. I remember it all, in fact it’s the last thing I do remember before a five-year period of my life that’s just…gone. Lost in a black hole of depression and indifference to anything around me.

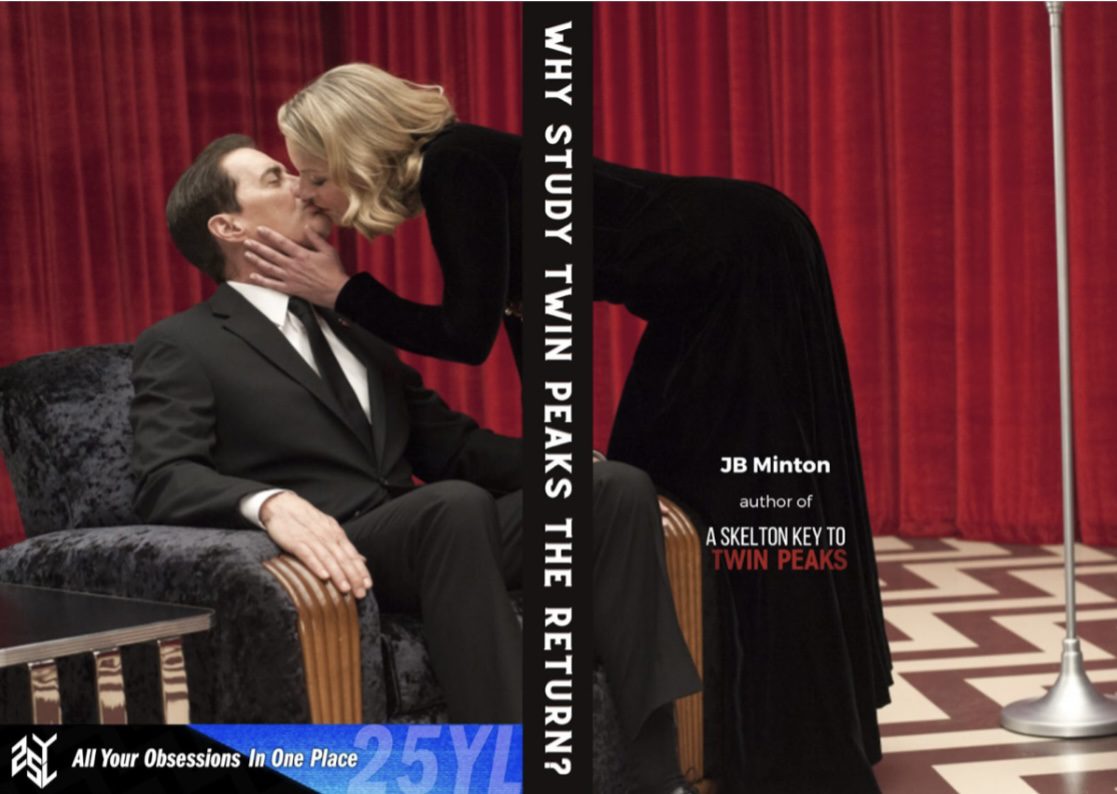

At the center of 2017’s Twin Peaks: The Return is the strange journey of Special Agent Dale Cooper, a journey that has already been the subject of a great many pieces and interpretations. A spiritual journey to fix himself. A metaphysical journey to try and defeat, or at the very least contain untold evil. An attempt to navigate a seemingly endless maze of timeloops and parallel universes and dreams—along with those who live inside them. But to me, it is above all else an unmistakably human one.

I don’t believe anything in Cooper’s part of The Return is metaphorical for suicide exactly. But beneath all the symbolism and spiritualism and reverse engineering of quantum physics and metaphysics and some third, even more convoluted form of physics, what Cooper goes through in The Return is very much the journey of a man who’s gone through an overwhelmingly traumatic experience and then must try to exist in the world as best he can. It’s one in which I see very much of my own struggles and my own journey—to borrow a phrase from Gordon Cole, I saw myself…I saw myself, from long ago.

So much of The Return is steeped in trauma and how we respond to it and try to continue on with our lives as best as we can, but nowhere is it as pronounced as it is with our beloved Agent Cooper. The change we see in him, from his almost relentlessly chipper, outgoing and curious demeanor to the passive, near catatonic DougieCoop has—for me at least—an uncomfortable sense of familiarity. The inability to communicate or connect with anyone beyond repeating or mirroring them, the passivity and indifference to what’s happening around him, the way in which he is almost instinctively drawn to simple and familiar pleasures…all of it feels reminiscent of my own change from talkative, inquisitive child and teenager to overwhelmingly closed off and quiet, passive adult. Even Mr. C’s car crash feels uncannily familiar, as my own attempt involved deliberately driving my car off a highway and into a rather large oak tree.

But, life must go on, and just as I still had to go to work and school in my barely functioning state, so too must DougieCoop attempt to live life as best he can—or at least, go through the motions of it. These certainly provide some moments of lightness and levity, a glimpse of normal, everyday life that Cooper so clearly needed but would never have sought out on his own, but this too has an inescapable undercurrent of strangeness and darkness. Does everyone around Dougie really not notice that he can barely function on his own? Or do they notice and simply not care, too busy with their own stuff to inquire further, to see if there’s a way they could bring him out of his shell?

It’s why that part of The Return never bothered me as much as it seemed to bother other people, eager to get their beloved Cooper back. Because I got it. No way in hell could Cooper—or anyone—go through such a traumatic experience and come out the other side fully intact. Rather than frustration at the sight of Cooper struggling to make his way through even the most basic functions of life, instead I felt empathy, and perhaps even a little bit of understanding. Because I had been there.

It even forms the way in which I understand (or at the very least, interpret) why Cooper does what he does at the end of Part 17: what he seeks is not only to—in his own mind—“save” Laura Palmer from her trauma, but to prevent his own in turn, rather than confront it and deal with it in a way that allows him to go on with life. To create a world in which he never went to Twin Peaks, never wound up trapped in the Black Lodge for 25 years—one might say, to be the dreamer who dreams and then lives inside the dream.

Frustrating? Yes, but also achingly, understandably human. I imagine most of us have some sort of trauma in our lives we would rather be without, and if given the chance would at least consider trying to escape to a world where it never happened. But as Cooper finds out, that entire way of thinking is wrong: not only would his actions rob Laura of both her agency and her place at the center of the Twin Peaks universe, but attempting to deny or escape your pain is no way to heal from it.

There’s an old saying: wherever you go, there you are. No matter what universe or state of flux our two main characters might find themselves in—alive or dead, Cooper or Richard, Laura or Carrie—they always find themselves drawn back to the Palmer residence in Twin Peaks, back to what was home to so much pain (and seemingly back to where the series all began with the voice of Sarah Palmer calling for her daughter). It’s still there, forever waiting to be confronted (or at the very least, no longer avoided) so that we may finally learn to live with it. The only way forward is through.

Thankfully it’s not all grim, as we do get to see what allows Coop to endure: love, along with a little bit of kindness, as corny as it sounds. The love he finds from his newfound family, the bonds he forms with the Mitchum brothers and his boss, even the love from whatever it is from Lodgespace or Lodgespace itself (I wonder if it’s not Laura Palmer, trying to give Coop a proper life after he all but gave his up to find justice for her murder), all of it winds up keeping Coop safe as he tries to muddle his way through. In turn, it was the love of my family that kept me safe and going as best I could as well, love that very likely helped me continue to steer clear from any hard substance abuse or any of the other difficult paths we can find ourselves on when we’re vulnerable.

As we watch the credits roll for that final episode, once again seeing Laura whispering in Cooper’s ear as she did in Part 2, I wonder how many times Cooper has gone around on this journey, and in turn reflect on how many times I’ve been around. How many times do we find ourselves avoiding our pain, even when it stares us in the face? How many times do we find ourselves at the door of our own Palmer residence, only to turn away rather than face whatever horrors we know are on the other side waiting for us?

I called a therapist this morning. I think it’s time I went inside.

Very interesting .Excelent article by Timothy Glaraton.

Thank you for writing this, Timothy ❣️

Thanks, Timothy – great perspective.