Part 10 of Twin Peaks: The Return features more than its share of disturbing moments. To my mind, however, the strangest and most visually jarring of these moments occurs late in the hour. Gordon Cole (David Lynch) sits in a hotel room where he is drawing with a felt-tip marker. Gordon hears a knock at the door, stands, and walks out of the frame, after which the camera dollies in for an upside-down close up on his drawing, which sports a long arm reaching for a fleeing deer or elk (the style understandably recalls the rough sketches of Lynch’s unchanging 1980s comic strip, “The Angriest Dog in the World,” although the deer/elk itself may be a deliberate reference to Deer Meadow, Washington, from 1992’s Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me).

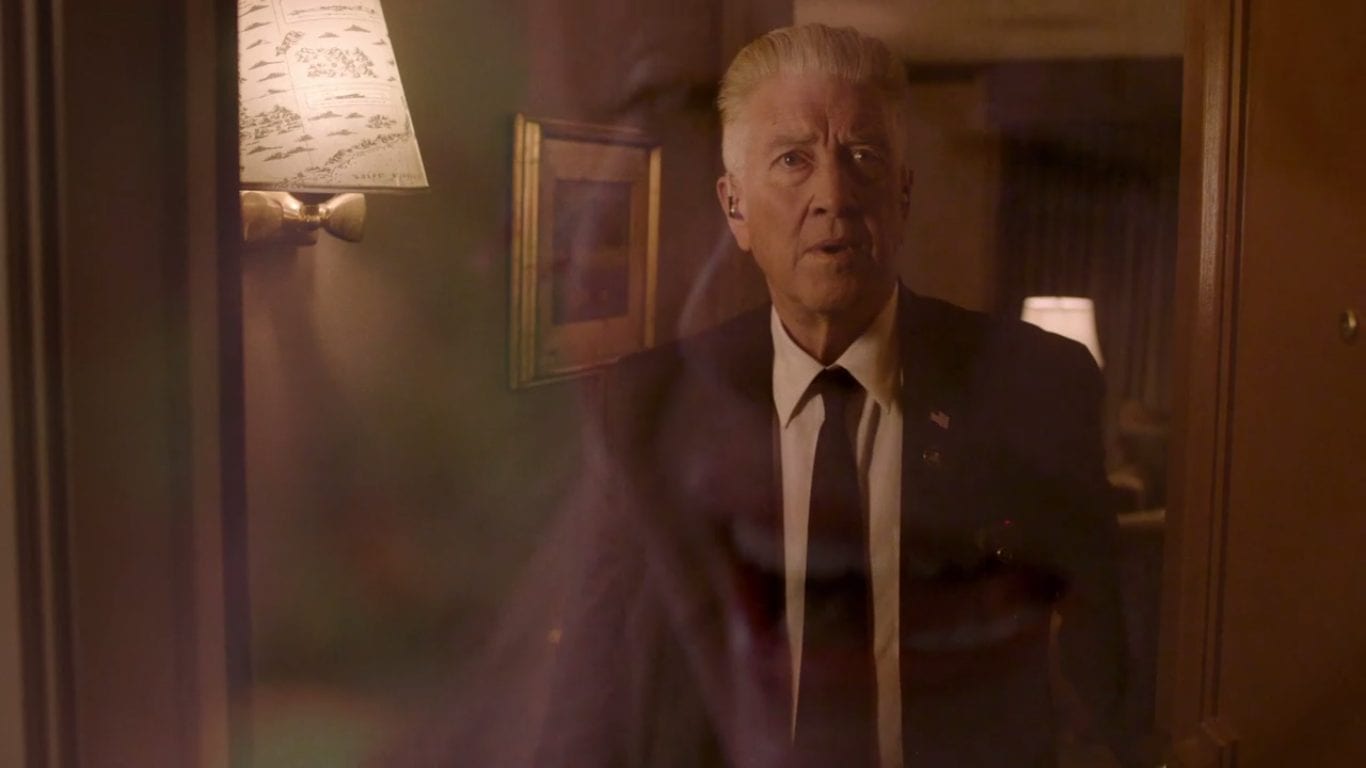

When Gordon opens the door, an oversized, disproportionate image of a panicked and sobbing young Laura Palmer (Sheryl Lee, shown here in a reversed and repurposed image from Fire Walk With Me) fills the frame. Laura’s cries are heard as a synthesized “horror-reveal” chord rises on the soundtrack. We see a view of Gordon’s bewildered reaction from the vantage point of the hotel hallway, a shot that places us on the other “side” of the transparent “Laura vision,” before we cut to Gordon’s subjective point of view one more time. We hear someone in the distance call, “Laura!” on the soundtrack (the sound seems to originate from within the vision itself), and the image of Laura begins to fade to reveal Albert Rosenfield (Miguel Ferrer) standing in the hallway. Another cut places us again behind the fading visage, granting us a final view of Gordon’s reaction to this strange phantasm, before a final cut shows us Albert in the hallway, looking behind himself to see what might cause such a look of astonishment on Gordon’s face.

In this article, I’m not concerned about what all of this means (although I’m just as ravenously curious as anybody else and have a few theories). Instead, I’m interested in Lynch’s mastery of his craft and the ways in which he induces dread and horror. Why does a sequence like this work for both Lynch and his audience? How does he manipulate, in a mere 20 seconds of screen time, the basic cinematic/televisual tools of image, sound, and editing to generate that unsettling drop of the stomach all of us collectively feel during this scene? There’s no doubt that Lynch possesses a unique and powerful style, composed largely of idiosyncratic sound designs, seamless juxtapositions of the horrific and the absurd, and camera movements and proximities that consistently defy expectations. And yet, like the best of our film auteurs, Lynch has adapted proven strokes of genius used by predecessors, most notably Stanley Kubrick (an oft-cited figure in studies of Lynch’s work).

Think, for example of Part 10’s most disturbing sequence: the shocking home invasion by Walken-esque sociopath Richard Horne (Eamon Farren). During this scene, I couldn’thelp but feel sick in ways that only Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange (1971) had previously induced through a similar—albeit even more violent—home-invasion that seems to have served as a reference point for the similar scene in The Return. Johnny Horne’s automated teddy bear (“Hello, Johnny! How are you today?”); the saccharine schmaltz of Montovani’s “Charmaine”; Richard’s, Sylvia’s, and Johnny’s screams in reaction to the escalating menace and violence—this combined visual and aural barrage owes a direct debt to the lunch-churning deployment of “Singin’ in the Rain” in that most infamous set piece from Kubrick’s dystopian film.

Or how about Part 11’s camera journey down the empty hallways of the apartment complex occupied by Gersten Hayward (Alicia Witt)? Lynch here employs Kubrick’s trademark fascination with single-point perspective and jump cuts—both used to great (and horrific) effect in Kubrick’s films, 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and The Shining (1980). Even despite his tributes to Kubrick, Lynch manages to make these processes his own (e.g., the darkly ironic twist of a hulking Johnny Horne, bound and gagged, forced to watch as his mother is abused and robbed by Richard in Part 10; or the manic acceleration of the hallway footage in Gersten’s apartment complex in Part 11). Lynch occasionally borrows techniques, yes; but he also builds upon what he borrows and turns a given technique into something new. And new technique is something almost impossible to achieve in the horror genre.

Part 10’s “Laura vision” follows this same practice of Lynch innovating a time-worn technique. The trope of a monstrous horror waiting beyond a closed door, soon to be opened, is old as the dark, distant hills. Kubrick’s The Shining, to name just one example, is replete with the dread lurking behind closed hotel doors and around blind corners. Here, however, Lynch overturns any expectations in numerous ways. He misdirects our attention at the beginning of the scene by encouraging our curious investment in the slow dolly in on Gordon’s strange drawing. This tactic leaves us unprepared and unguarded for the visual and aural shock soon to follow.

While we are busy trying to understand the significance of an extended arm reaching for an upside-down deer/elk possessed of antlers that resemble trees, Lynch next moves on to the opening of the hotel room door and the wholly unexpected appearance of the outsized image of Laura, which,in both its grossly disproportionate size and its deliberate “fakeness,” invites a sense of immediate dissonance between the slick trappings of The Return and this otherwise low-rent superimposition effect. What’s of interest, too, is the fact that the “low-rent” effect of the Laura superimposition seems, in some ways, to be the source of the tension we feel in the scene.

This footage from Fire Walk With Me seems so derivative—as if it is a bad, fourth-generation copy of that film’s 1993 pan-and-scan VHS tape—that one can’t help but wonder whether Lynch is making some kind of commentary about the nature of the media on which we preserve our moving images. I’m not prepared to “go there” in this article, but the quality contrast between the “Laura vision” images and the otherwise sleek images inherent to The Return certainly demonstrates how Lynch can draw on different kinds of media to create certain aesthetic and emotional effects in The Return that feed his larger narratives about interdimensional travel and communication.

Interesting, too, is the fact that Lynch takes pains to show us that the “Laura vision” itself seems to be two-dimensional (as if it is screening on a flat surface—but without a screen present), and that it can be seen (at least by the show’s viewer) from either one side or the other. Our view of Gordon “through” the “Laura vision” also reveals that the whole of Laura’s head in the vision is as large as Gordon’s upper body. In other words, the disproportionate size of the “Laura vision” is shown to be an act of purposeful design, the intended effect of which is to bluntly disrupt the viewer’s presumptive complacency about the way Gordon’s world works. The “Laura vision” is, in fact, a textbook example of Freud’s description of the uncanny.

The term is used to describe how the familiar takes on a quality of unfamiliarity and how this sudden unfamiliarity of the otherwise familiar sends a chill plummeting down the spine. We think we understand what’s coming next, because everything—the characters, the setting, the cinematography—seem normal. Blandly predictable. Even if something strange lies in wait beyond the door, we believe we’ve seen enough horror films to know things can’t turn out all that badly. But Lynch relies on our making this cynical assumption. Like Kubrick, he knows that the true nature of horror rests not with the jump scare, but rather with the disquieting recontextualization of everyday things. The slow zoom on the dismembered ear covered with ants in Blue Velvet (1986); the log fire that burns at a fantastically accelerated pace in the Madison home in Lost Highway (1997); the incongruity of a long road trip undertaken on a used lawnmower in The Straight Story (1999); the shocking and sudden appearance of the homeless person behind Winkie’s in Mulholland Drive (2001); the terror-spawning, warped-faced grin of the Phantom from Inland Empire (2006); all of these Lynch moments gain their cinematic value from the fact that they straddle the familiar and the unreal, the prosaic and the surreal. Lynch employs this uncanny straddling technique in The Return to great effect, and the “Laura vision” sequence stands as just one of these. The scene reminds us of how we become truly frightened—through the transformation of the comfortable into that which feels suddenly disorienting and alien to us.

Hi Douglas A good article. Nice to hear someone engaging with the uncanny.

It’s also worth noting Heidegger’s uncanny is being deployed here also, in that we the audience, and Cole in the show, are thrown out of the world and out of time by this occurrence and this in some ways signals the absurd through the liminal space of the show and the realms within it. I say the absurd because while many writing about the show point out it’s absurd sense of humour they ignore that absurdity, and it’s existential cousin, are highly intertwined with dread, loathing and melancholy. A great example of this is encapsulated in the scene you analyse. When Richard enters his grandmothers house, Johnny knocks his own chair over in an attempt to come his mothers aid. He can’t reach her of course because he is tied to the chair and also restrained by his own cognitive dissonance. Despite all he attempts to get to his mother but is left, because of his restraints running on the spot, with his legs and arms uselessly motioning in the act of running like Sisyphus eternal crossing treading the same path. This is at once absurd and humorous but also terrible, for Johnny and his mother. He and she both stand at the edge of the abyss, in an uncanny space created through violence, leaving her, momentarily, and her and her son, permanently, in a state of anxiety and despair, unable to stop what is happening or to comprehend it.