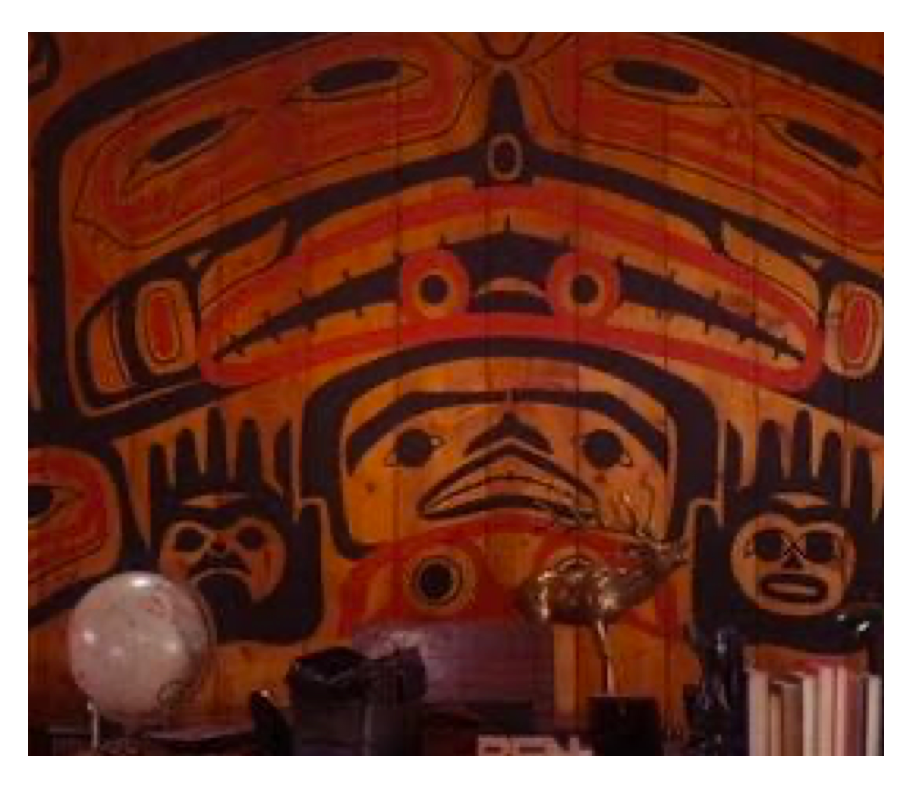

The Northwest Coast Chief of the Undersea World, Konankada, perhaps akin to Hades or ‘Death’, shows up in Ben Horne’s office during key moments in all three seasons of Twin Peaks, yet is never acknowledged by characters within the show nor within Twin Peaks scholarship. As an ‘invisible environment,’ a manufactured copy, a type of sigil magic, mythos, and coping mechanism, this complex character coincidentally reflects on Twin Peaks themes and is worth another look.

Here is the original Konankada (Haida) design—Gonankadet in Tlingit, Komokwa in Kwakwaka’wakw, Hakulack in Tsimshian—carved and painted on a bentwood burial chest living at the Canadian Museum of History in Gatineau, Quebec.

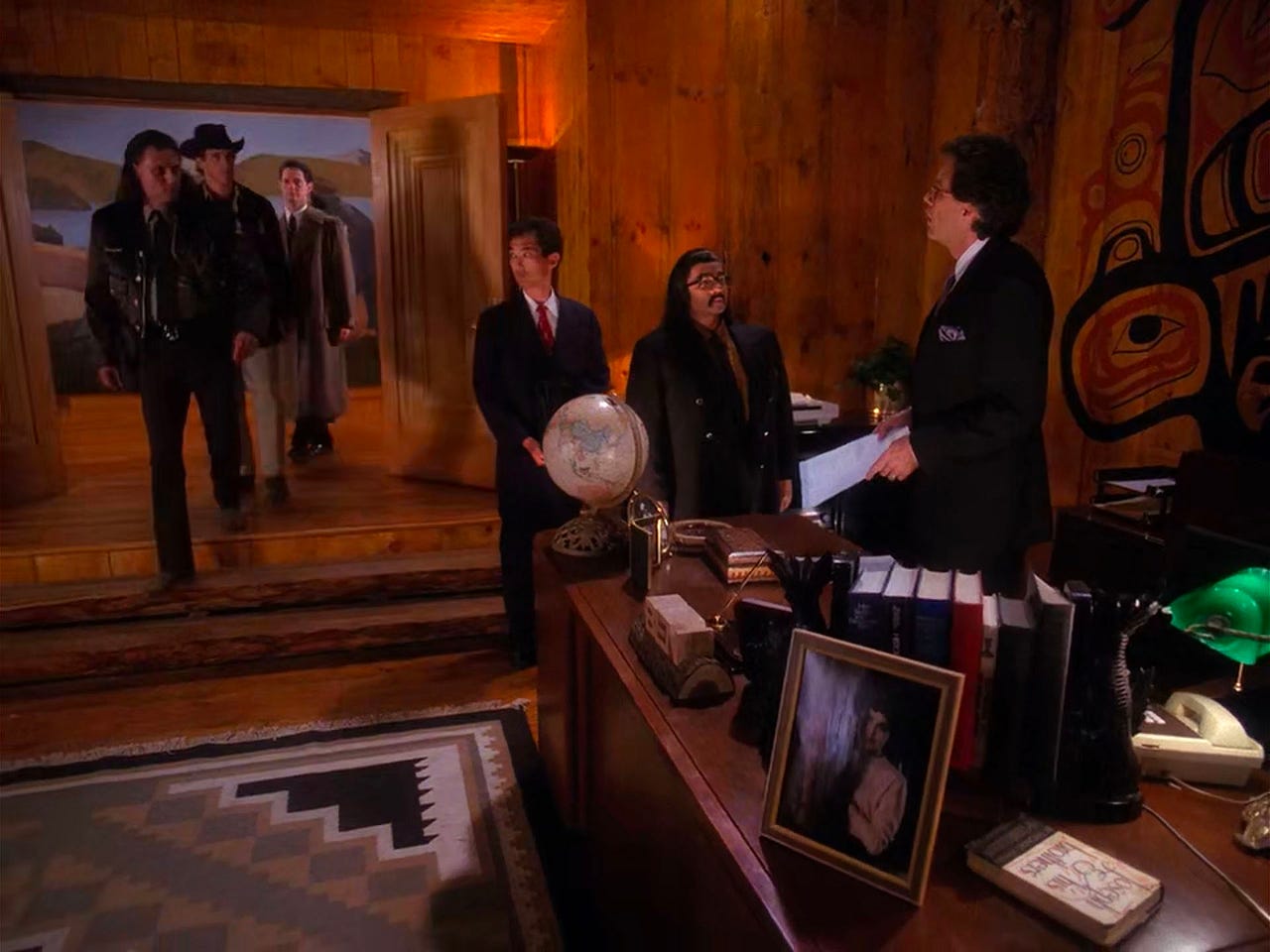

The image painted behind Ben’s desk is an (almost) exact copy of the burial chest. Look at that! The unknown artist (probably Bella Bella/Heiltsuk) responsible for the original design has a style—their economic use of finelines, circles, crescents and trigons—but the overall image is a fairly typical burial chest design found along the Northwest coast. Traditionally, these elaborately carved and painted chests are inserted into totem poles, or they’re burned and destroyed at potlaches. Sometimes human remains are placed inside the bentwood box and then burned, then the mixed ashes are interred in the totem pole. In a sense, the abstract orca behind Ben Horne’s desk transforms the Great Northern into a giant ghostwood coffin.

The design is foreboding, yet is traditionally used for protection, and good luck. We are looking at a painting of—and for—the God of Death. Orcas (from Orcus, the Etruscan god of death) got their nickname because they prey on other whales, and how appropriate, then, that it’s a Horne family crest, a family known for predation. None of this seems to matter, though, for it is never talked about by any characters within the show.

Beverly never says, “Why is that Haida tribal crest design in your office, Ben?”

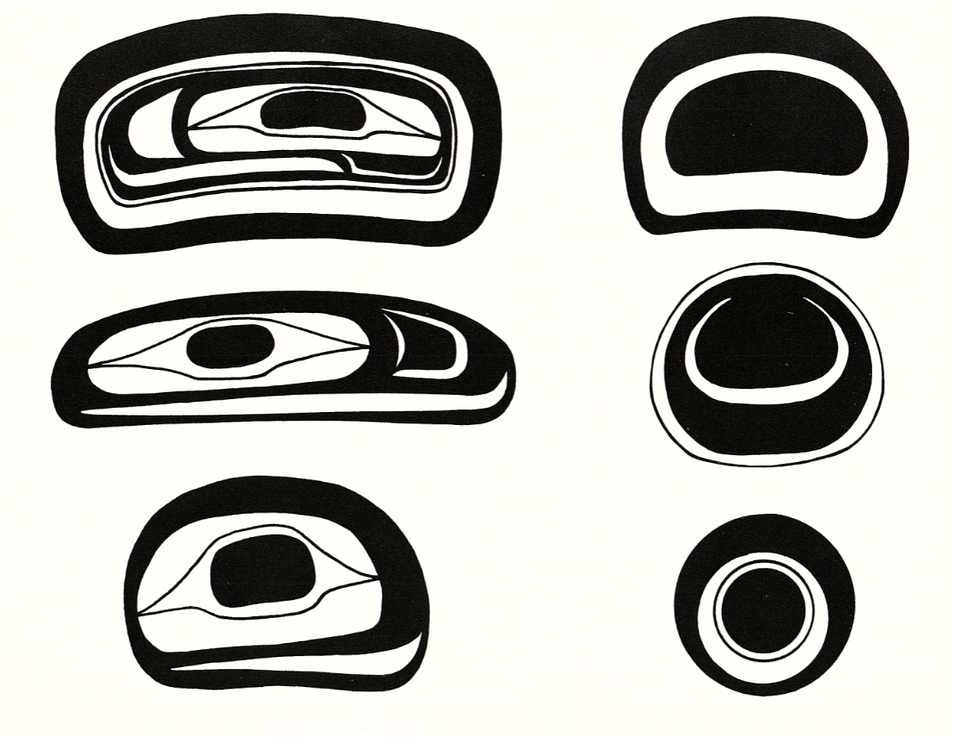

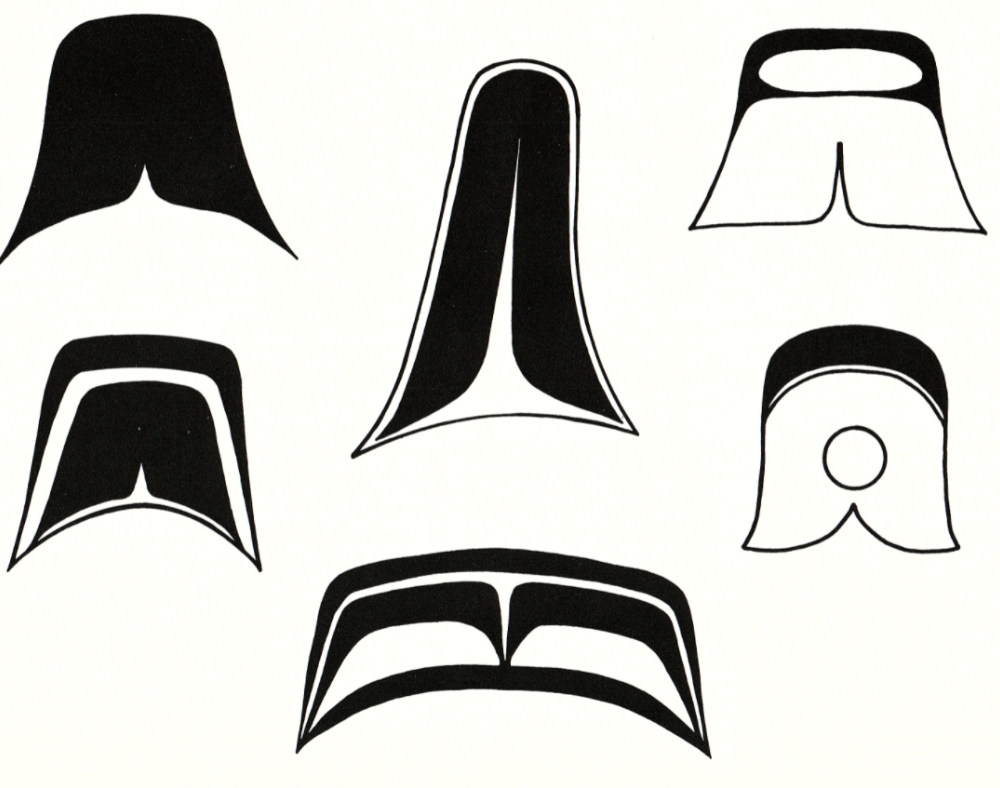

The inimitable drawing style is called “formline” (Bill Holm’s term) and is one of the most sophisticated and mind-boggling drawing styles in the world. The lines have form! The formline technically refers to the thick, continuous black outline that manifests the main character in both positive and negative space. Thinner and more colorful secondary and tertiary lines (sometimes called finelines) fill up the negative spaces of the primary design with more beings, creating an evenly balanced composition. Familiar yet wholly Other, everything is distorted; figure and ground oscillate like an M.C. Escher tessellation; hard-edged black, red, and clear shapes (the bare wood) follow very specific rules; eyes are everywhere.

All the parts fit together like a puzzle. If you look carefully, there’s a humanlike person at the bottom, probably Nagunak, hands up with a face inside each palm. I’m reminded of the hand inside of Sara Palmer’s face, an inverse of this motif, and it looks like Laura and Sarah holding their excised faces in their hands. The humanlike person’s Saturn-eyes and sixth fingers are not found in the original bentwood. Other beings, most notably the “salmon-trout heads” that resemble Eraserhead babies appear in the four corners. Tsimshian artist David R. Boxley teaches that some beings in a Konankada design are getting sucked into the whale killer, who is emanating from the person in the center.

People get consumed. There are eyes within eyes…within eyes. The huge portrait shrinks everything and everyone around it. I count twenty-six eyes, two of them with clear pupils, like doppelgänger eyes. It’s more present in this way, even when unnoticed, than the other characters.

Like Twin Peaks, the painting is really a portrait of a team of beings, and a sort of map: each design represents a place and ecology. Thomas Thornton, in Being and Place among the Tlingit (2008), calls formline beings like this one “settings,” “spatio-temporal genres,” and “chronotopes”, literally “time-space,” after Mikhail Bakhtin, who borrowed the term from Einstein’s theory of relativity. Thornton then compares them to European landscape paintings, “because they both explicitly appropriate and idealize places and therefore shape the perception and experience of those landscapes.” Myth-making becomes deep-mapping. (See Do you understand a place?)

Western art historians might call this type of image a hieroglyph or hieroglyphic language—from the Greek hieros, “sacred,” and glyphein, “to carve“. Western anthropologists and archaeologists would call this a fetish, from the French word for fiction, originally used to describe any tribal art object European scholars couldn’t understand. Foucault might call it a heterotopia, “spacial creations of an ‘other place’ that belong to the network of sites (emplacements) in a particular culture, yet at the same time are not part of the trivial continuum because their inner rules are stubbornly autonomous, often running counter to the logic of the whole.” Foucault names cemeteries, monasteries, libraries, brothels, and cinemas examples of heterotopias. Peter Sloterdijk thinks pilgrimage sites, sports venues, and space stations are also heterotopias, and adds that, with the space station, “it’s easy to show that a specific form of astronaut spirituality has developed there.”

More and more faces appear the longer you look at the painting due to the plethora of bean-like “ovoids”, what Steve Brown calls the “grandmother of designs,” because they can represent heads, eyes, bones, and joints. Haida artist Lyle Wilson, in Origins/Coalition (2011), explains that the inspiration for the ovoid shape began with the prominent eyespots on the wings of stingrays, then the white eyespots on orcas, and then they merged with the more squared eyeholes of the human skull. In a sense, when we look at ovoids, we’re looking through eye sockets.

There are beings who live behind people’s faces. “I’m a whole damn town!” Think of Cooper’s face superimposed over everyone in the Sheriff’s Station. Within Konankada, one can see examples of “double eyes”—where each of the main character’s huge eyes contain two more eyes. And, we can find examples of “split representation”—a mirroring or doubling of an image to expose two sides of a single being at once. It’s not two heads; it’s one cut in half and spread open. (Not two Coopers; one divided); a mirrored profile of one orca with an orb in its teeth. Janet Berlo says formline images can therefore be mentally “wrapped” around a three-dimensional surface before carving.

We are basically looking at higher dimensional space mapped into lower dimensional space—a 5D entity imagined in 4D, translated into 3D through a 2D drawing. Here, the imagination is perhaps better understood as an ‘imaginal realm’ (Henry Corbin’s phrase), which is like an etheric film that mediates the terrestrial and spiritual domains, or a vibrating field between mind and soul that picks up on certain signals and turns them into visions and art.

Talk about “catching the big fish”! Konankada lives along the coast… lives, or exudes? It could be as David Spangler recently put it to Connor Habib: there are subtle beings who are not ego but eco—ambient conditions that make up a place; local spirits who manifest the affordances of an “experience” of a place; the Pan in panpsychism. These protean phenomena can unfold and enfold like the Interstellar tesseract or Thomas Aquinas’s angels: not physical creatures in space, but “beings that created out of themselves the space that they illuminate and animate with their essence” (Sloterdjik 2017:190). They’re not in space, they inhabit or haunt space.

Berlo says each ‘design element,’ like an ovoid or U-form, represents many different animal body parts, and therefore encourages “visual puns,” making them more hieroglyphic. Tsimshian artist Terry Starr argues, for example, that the tails on some beings also qualify as wolf cubs. If you know the code, you get the stories. Even if you don’t, these designs are mind-expanding. Like our Twin Peaks, formline designs, “play on fundamental philosophical perceptions of structural dualities, the deceptiveness of appearances, mythic processes of transformation, and the paradoxical coexistence of two truths as a single juncture in time and space” (Berlo). What a ‘happy accident’ that they appear inside the Great Northern Hotel!

We must also try to understand that some designs qualify as “cultural patrimony,” or communally owned objects (like bones) that in the US fall under the repatriation laws of NAGPRA. They’re living symbols with (copy)rights and responsibilities. Anthropologist Sergei Kan writes that, for the Tlingit, formline crest designs are “the most important symbol for the matrilineal group, as well as its most jealously guarded possession.” (Check out the story of the 1996 repatriation of a Tlingit Killer Whale clan hat valued at over $150,000). In the past, the gifting or earning of these designs sometimes even involved human sacrifice, because the designs serve as a kind of guardian, shield, and official record of a clan’s history. They are “intangible property,” with a spirit-being and a place “behind” them, linking a particular group to a particular terrain. What the hell are they doing in the Great Northern? What are they doing in a David Lynch film?

Background’s Background

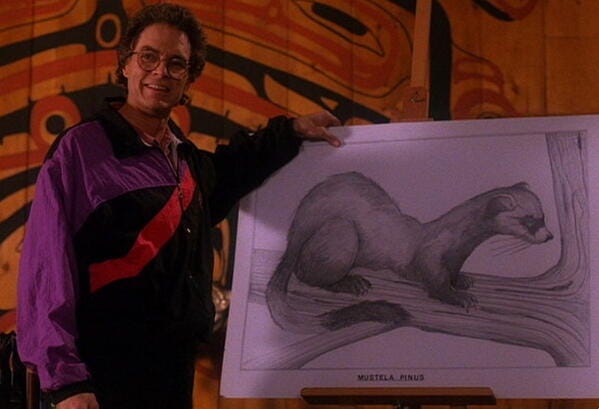

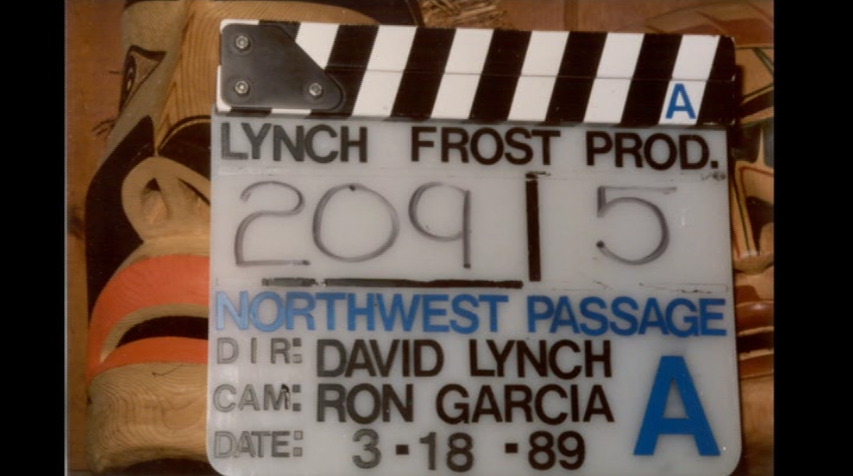

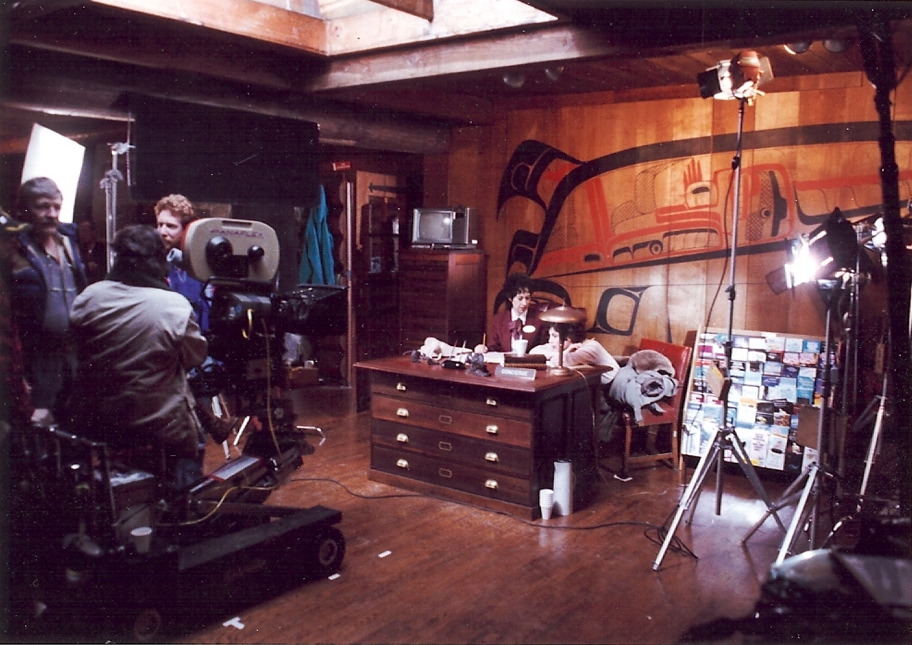

Like the floral wallpaper and red curtains, this complex funerary hieroglyph is now an iconic backdrop in Twin Peaks. Who decided it would be Konankada? Richard Hoover, in charge of the L.A. sets for seasons 1 and 2, told me via email that two “scenic people” worked on Ben’s office, David Robinson and Ann Elias, “David the first season and Ann the second,” both non-Native artists as far as I can tell. Neither got back to me, and Hoover couldn’t tell me who decided to copy the Haida coffin design specifically. A real mystery! I imagine someone, maybe it was Lynch, selected it from an art history book, or saw it in person at the museum in Gatineau and took a picture. Remember this was before the internet. Please comment below if you know anything!

Did they understand the meanings of the crest design? Does Ben know of its power of protection? Does it matter?

We don’t know why this bentwood image was selected, but we do know why the owner of a hotel and spa in the Northwest would want formline art in their lobby:

- Because that’s what tourists want. That’s what we expect to find when visiting ancient American sites: something “authentic,” something “Indian”—”Native Otherness” (Renisa Mawani’s term).

- Because it makes us feel something! Non-Natives collecting Native art is typical “imperialist nostalgia” (Renato Rosaldo’s term), where settlers yearn for and “celebrate” the cultures they’ve destroyed. Rosaldo also calls this “mystification,” and it’s part of why the U.S. names its cities, states, streets, summer camps, schools, cars, corporations, military helicopters, troops, and sports teams after Indigenous cultures. Idealized fantasies gloss over violence and brutality. It’s why Lynch/Frost lean so heavily on Native imagery in Twin Peaks, and why the fans love it all some much.

- Turning your home or establishment into a miniature Native Art museum is part of a 150-year colonial tradition. They were called Indian Dens and Indian Corners, bric-a-brac displays of mostly baskets, masks, and taxidermy animals, complete with glass vitrines and museum labels. If you look carefully, The Kiana Lodge/The Great Northern in the pilot is in fact a basket museum. Marshal McLuhan: “The previous environment becomes a work of art in the new invisible environment.” Settlers remove Indigenous people and replace them with their art. We can see this pattern exaggerated in the park-enfolding Crystal Palace of the 1851 London Exhibition and its “festival of empire”, or we can see it take shape in Disneyland’s “It’s A Small World” ride with its hyperreal “simulated imperialism” and so-called Disneyism that helps Americans distance the evil of conquest and genocide.

Deputy Andy: “I haven’t found any Indians.” This pattern reaches all the way back to the beginning of empire: Romans loved to surround and domesticate symbols and artworks of the Indigenous. However, the Egyptian statues and Nilescapes that decorated dining rooms in Pompeii tell us more about the Romans than they do about the Egyptians. Likewise, the formline paintings, totem poles, and trade baskets of Twin Peaks speak most about Lynch and Frost, their production, and their non-Native characters’ “imaginary Indians.”

Playing Indian

It’s so American to ‘play Indian.’ Ben Horne plays Indian by making his office look like a typical Pacific Northwest clan house. His full-grown son plays Indian, too, intensifying the pattern. In the pilot episode, Johnny wears a fake Indian headdress and bangs his head against a doll house that resembles the Great Northern. What an image! In another episode, he can’t take the fake headdress off without it causing a lot of pain. Later, Johnny pretends to hunt buffalo with a kid’s bow-and-arrow. Maybe he’s the reincarnation of Boy Scout founder Ernest Seton! (In 1904, Seton wrote a book called, The Red Book: How to Play Indian.) David Lynch, as a proud Eagle Scout, is guilty of ‘playing Indian,’ too, but so are all settler Americans, to some degree or another. People in the US even perversely call Indigenous peoples ‘The First Americans.’

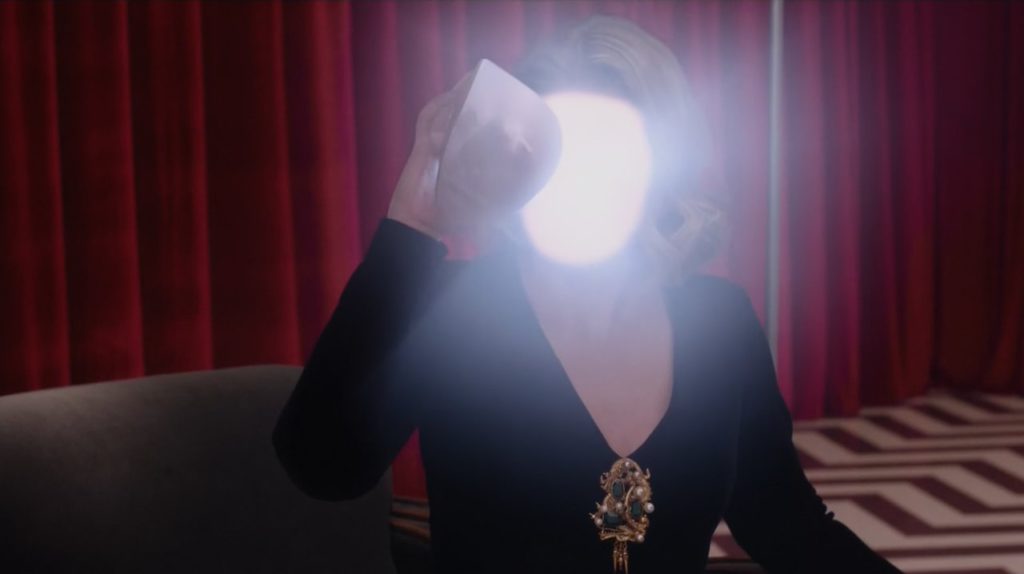

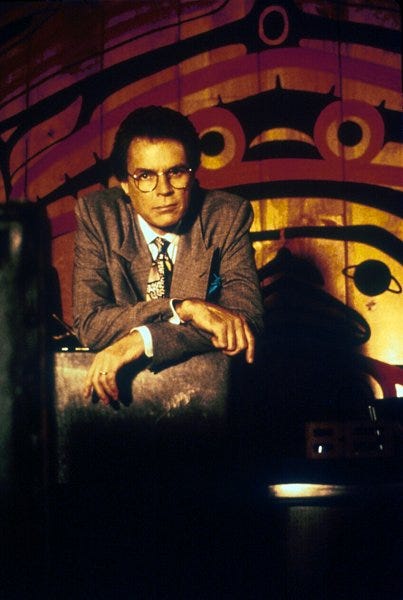

The second episode Lynch directs opens with a long shot of the Horne family eating dinner in what we assume is their dining room. For an entire minute, a ‘Lynchianly long time,’ the camera does not move or cut away, so we get a good look at the ‘moving painting’ constructed for us. A manufactured Konankada frames the shot and looks directly into the faces of both Ben and the viewer. Nobody speaks. Johnny is the most animated, wearing his fake Indian headdress, sitting Indian style in his chair, and mumbling incoherently beneath a soundscape of crickets, frogs, clinking silverware, and eating sounds.

If we read Lynch’s mise-en-scène as a painting—as he probably intended—it’s basically a picture of white people playing Indian. Philip J. Deloria, in his book, Playing Indian, explores why settler Americans often need to feel Indigenous, even if only for fun. It’s essentially a coping mechanism—a way to alleviate the pressure and horror of living on stolen land.

This existential coping goes all the way back to the Boston Tea Party, when settlers put on Indian costumes to invade British ships, and it takes shape in the very first U.S. fraternity named, get this, The Improved order of Red Men. You can see images of them online dressed up like Johnny Horne and members of the Boy Scouts. Playing Indian also echoes into sports teams, New Age wellness events, and German Indianthusiasm, which has apparently developed into a profitable industry throughout Europe.

But these sacred art objects aren’t just victims of kidnapping at the whim of some settler who tells them what to do. University of Chicago’s Isaiah Lorado Wilner argues that Northwest Coast artworks have agency of their own and act as “mnemonic devices that archive the global propagation of knowledge”—they’re not a ‘ghostly specter’ but an active resistance. Wilner speculates transformation masks specifically became a “survival strategy” that “utilized the anthropologist Franz Boas as a host body to enter and alter the world that came to colonize them.” In analogous fashion, powerful Pacific Northwest tribal artworks made their way into one of the (if not the) greatest television shows on earth! What are they doing to us unawares?

I imagine David Lynch, in early January, 1989, arrived at the Kiana Lodge to check out a potential filming location, and, without warning, was pulled into the monumental paintings and glass boxes filled with zig-zag Squamish baskets — two motifs that will echo all the way into 2017’s The Return, when Cooper finds himself lost in a chevron pattern, and then floating inside a giant glass box.

The place made up Lynch’s mind.

It’s horrible, this settler colonial coping mechanism, and it’s part of what we might call the geometry of Twin Peaks. Next to that history, a mystery: images from “myth time” painted on the walls, cafe menus, and Great Northern security guard uniforms.

White Carver

The painting looks like a Tlingit screen. The ‘original’ formline designs and totem poles at the Kiana Lodge were created by Duane Pasco, who is not Native, and even though he’s a well-known, respected artist, his work still signals a persistent problem. I asked Nicholas Galanin about this, and he pointed me to his 2012 installation and performance called White Carver. I think Galanin does a great job at describing a form of colonial violence that happens whenever settlers appropriate Native art for decoration. In the performance, a white, non-Native male artist in an apron sits on a stool, whittling an object. Behind him, portraits of past “White Carvers” hang on the walls. Next to White Carver is a ceremonial “fetish” object he is copying: a life-size fleshlight or “pocket pussy,” carved by Galanin out of yellow cedar. The sculpture is gorgeous, but also “doubles down on fetish,” Galanin says. “The masturbation tool has a singular function—to satisfy desire without intimacy with a partner. The fetishization of the pocket pussy as a small part removed from the physical, mental, and emotional wholes of a person stands in for the small part of the Pacific Northwest indigenous culture that is fetishized and separated by non-indigenous consumer culture.”

Settlers take what they want and leave the people behind. This is happening behind Ben Horne’s desk. It’s happening in Twin Peaks.

Copying, coping, coopting.

Globes and Screens

One could almost say that, with this painting, the ‘wild’ and ‘spectral’ Native Otherness is domesticated by its constant proximity to computers and other items in the room, while the chair, desk, globe, and books are imbued with an other-worldliness. It’s clear Konankada doesn’t belong here, in this hotel and spa, and yet they’re also perfectly at home, speaking truths about settler colonialism and Indigenous survivance.

Let’s leap off the wall to notice the globe that turns the many-eyed Konankada into a Lovecraftian planet-sized monster—maybe Azathoth opening its eyes? The globe is a miniaturization of an entire planet, so we get a ‘god’s-eye view’ of Gaea and Konankada, now the Buddhist Mara eating the six realms of being. It’s the experiment vomiting up a BOB-orb in Part 8. Revealed as a lamp in the production photograph above, the globe is the Laura orb floating towards her fate: a screen.

The art-decorated room brings the globe within the scope of art. McLuhan talked about how satellites enclosed Darwinian “Nature” by putting the planet inside “a man-made environment,” therefore turning the whole earth into a cultural artifact. It’s that pattern again, also expressed in how David Lynch is collected as an art star, along with Twin Peaks merchandise and books. The show and its creators are miniaturized and collected as art in a new invisible environment.

More maps: Originally globes were navigational tools for ships. Now they’re ubiquitous props in elementary school classrooms. We’re placed into a childish environment observed by a many-eyed god. Looking at the globe from afar suggests we’re diving towards it, recalling William Thompson’s memory of seeing Disney’s Fantasia as a child: “I became that soul again approaching the planet earth to accept a human incarnation; it wasn’t a metaphor, it was a memory.” (The American Replacement Of Nature, 1991). Darren Aronofsky visualizes this angelic descent in Noah (2014), as Lynch does with the Laura orb floating into the projected revision of the 1930s Universal Pictures logo. “Faster and faster.” Isao Takahata, in The Tale of Princess Kaguya (2013), depicts the reverse—a soul floating up to space, looking back at earth, and forgetting nearly everything.

Mystical Americana

Twin Peaks is unlike any other television show in that it’s written, directed, and staring an avant-garde artist and spiritual leader, David Lynch. Ever since Maharishi Mahesh Yogi passed away in 2008, Lynch has been the face of Transcendental MeditationTM. He does a lot of meditating, but that doesn’t give him or Frost an easy pass to use Native American imagery in their art. The decision to cast and copy this artwork is serious business. Any representation of Indigeneity in the US is serious business. And it’s not only copies of Native art: real native artifacts are deployed in the show. Did they consent? Does it matter?

Conclusions

The formline painting behind Ben Horne’s desk is a “spectral index of the people and coexistent beings who’ve been practically erased from the Pacific Northwest ecosystems”—as Andy Hageman puts it in David Lynch and the America West. Coincidentally, for Twin Peaks fans, the painting connects with Twin Peaks themes, like doubles, maps, woods, hauntings, missing people, settler colonialism, playing Indian, and other-than-human beings living within our walls. Both the painting and television show suggest a haunting by a still-living, now-dissociated way of being that the characters cannot see, a presence in the room there to observe them. Franck Boulègue calls Lynch’s layering of information “subliminal superimpositions,” and I think we can creatively apply that idea to our appreciation of the formline design: It unconsciously colors our worldview and mythos. Pay attention. “Very important! Very important!”

Konankada and Twin Peaks engender a trans-human sense of nationhood. They encourage us to step outside our sense of self as a contained being and into an unending field of entangled more-than-human entities. The painting and show pull us into higher dimensional space and myth time. When we zoom out, we perceive a ‘deep map’ of surrounding historical contexts, and we feel deep structures and local agencies beyond our control.

Notes:

•What’s in the ghostwood? The sound of a ceiling fan? What happened to Josie? Timothy Morton thinks Naido’s voice is Josie’s squeaking door-nob.

• The fetishistic consumption of Native art in Ben Horne’s office resonates with the fetishistic consumption of other things in Twin Peaks, like women and sandwiches. See David Lynch and the American West for more examples. It’s a damn fine book!

• Raven family uses whale crests. Eagle does not.

• There is a belief that humans reincarnate as killer whales.

• In one story, Konankada invents the potluck/potlach ceremony to honor Raven, a trickster god, for using a scratching sound to lure humans into the world. See Bill Reid’s 1983 Raven and the First Men for a 3D version of this story.

• Tricksters got us into this. Raven used a sound, and there’s a Japanese story called Amano-Iwato, where gods use music and a mirror to get Amaterasu to come out of her cave.

• Alfred Gell calls complicated designs like this a “technology of enchantment.” He focuses on the bold patterns painted on battle canoes and argues that complex designs are distractions and can be classified as psychological weapons because they stun and disturb normal cognitive functioning. The “opposed volutes” lead the eyes off into opposite directions, throwing people off. Gell jokes that when an ethologist sees complex symmetry in tribal artworks like this, they mutter ‘eye-spots!’ and start pulling out photographs of butterfly wings with similar markings designed to have an effect on predatory birds.

• In Ritual and Myth, W. Jackson Rushing chronicles famous American avant-garde artists from the 40s and 50s, self-identified “mythmakers,” who were inspired by totem poles, formline designs, and Navajo rugs. Lynch is part of this lineage.

• The art is fine-tuned to a specific place. Peter Sloterdijk, inYou Must Change Your Life (2016, 222), compares this kind of sacred site-specificity to Foucault’s ‘heterotopias’.

• In Episode 2, when we see Konankada against the back wall during the Horne family dinner, I can’t help but think of the convenience store scene in FWWM, where lodge entities are lined up against the back wall.

• See Tsimshian Soul Catchers and Raven Rattles for more mind-boggling 3-D hieroglyphics.

• Totem poles suggest a vertical axis of nested beings, with below not meaning “less than”. The phrase low man on the totem was originally a euphemism for the US taxpayer, and does not apply to actual totem-pole carvings, which are not arranged in a typical hierarchical order.

•Totem poles, formline paintings, masks and baskets, have come to symbolize “authentic” Native art that is desired and consumed by tourists. Yet, this perceived authenticity is premised on inauthenticity: on a singular, homogenized, imagined and “fixed” Indigenous identity that doesn’t capture the complicated and diverse histories and experiences of real Indigenous communities in the Pacific Northwest. This is how ‘representation’ can eclipse and erase cultures, and why Native mascots make us stupid. See Paige Raibmon, Authentic Indians: Episodes of Encounter from the Late-Nineteenth-Century Northwest Coast, 2005; and Renisa Mawani, From Colonialism to Multiculturalism?: Totem Poles, Tourism, and National Identity in Vancouver’s Stanley Park, 2006.

•On their website you can take a digital tour of the Kiana Lodge and examine some of the chevron baskets that were likely there in the early ’90s.

•All the Native art we see in the pilot—the masks, totem poles, baskets, paintings—were collected by Robert “Bob” Riebe (1937–2009), the previous owner of the Kiana Lodge. His collection now belongs with the Suquamish Tribe, who purchased the lodge from him in 2004.

Deeply thoughtful, stimulating, and question-rousing. Tremendous research, as well. Thank you David.