The fig leaf was brown.

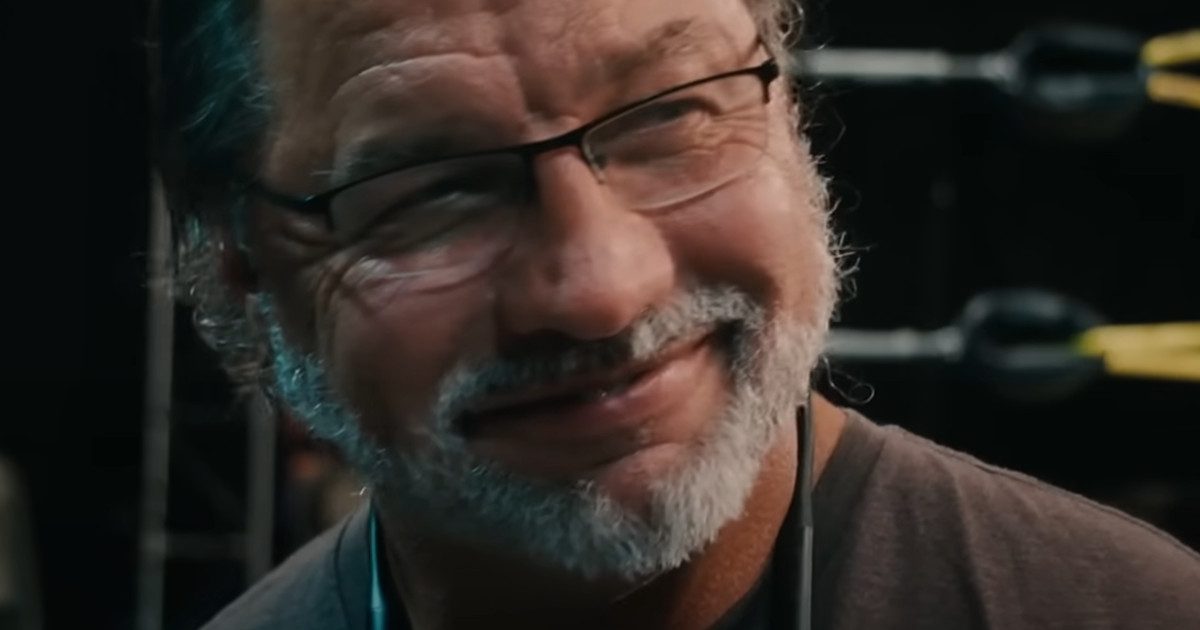

This essay examines David Lynch’s scatalogical art and argues that it could be the fastest way out of our heads. There is no other matter so vehemently repressed, hated, and dissociated than feces, and yet we are full of it! We are shit factories disgusted with our own product! What an oxymoron. Shit is so laden with significance, it’s an “entity” or “phenomenon” with agency at this point. David Lynch works with this forbidden fruit, as many artists like to tap into what Paul Rozin coined “benign masochism”—experiences that are pleasurable because they are disgusting. It turns out, mingling with the disgusting and the “wild” does wonders for the imagination.

Shit points to something universal. Lynch got into trouble with ABC when he decided to put dog turds in Mulholland Drive (2001). He argued, “Show me someone who hasn’t seen dog shit!” ABC pulled out of the project.

Why is crap so taboo? Rozin thinks it foreshadows our own rot, and humans have evolved to avoid rotten foods and anything that can make us sick. James Brain, in The Last Taboo (1979), says everything boils down to the death terror. In Orifice as Sacrificial Site, James Aho draws attention to this repressed thanotophobia by examining different holes in the body and “the density of personal obsessions and ceremonies” surrounding their excreta. Like the rest of us, he uses a “mental revulsion scale” for judging excretions in terms of their symbolic proximity to rot/death/fecality. Tears, according to his scale, are the farthest away from death, “hence the least revolting and the least subject to regulation.” They can be touched and even kissed without a problem. Neuroscientist Rachel Herz explains this is because tears are mostly water—yet they still contain “excretory elements”. Next is hair, then sweat, wax, nail clippings, oils—all gross but not that gross—followed by spit, snot, urine, blood, vomit, and then feces. Feces is closest to death. Brain quotes Indigenous leaders in Tanzania as saying, “the corpse is filth, it is excrement.” The Bible also calls dead bodies “dung upon an open field.” We bury our shit and our dead.

Another theory is that we find anything that reminds us of our animality disgusting, “the animal reminder factor,” and human people go to great lengths to ignore the mountain of evidence that we are, in fact, animals. Not only shit but the whole anogenital region is associated with animality, the wild, death and sex. Yeats: “Love has pitched his mansion in the place of excrement.” Aho: “Its animality is sublimated, hidden from view, and refined into romantic love.” Sex is dirty and dirt is sexy. Really all sex is associated with fecal matter (not only gay male sex). Thoughts of shit and actual fecal matter mix with kissing, licking and “eating” during love making, as normal taboos and aversions to body fluids are momentarily suspended. (Otherwise, we wouldn’t be able to do it).

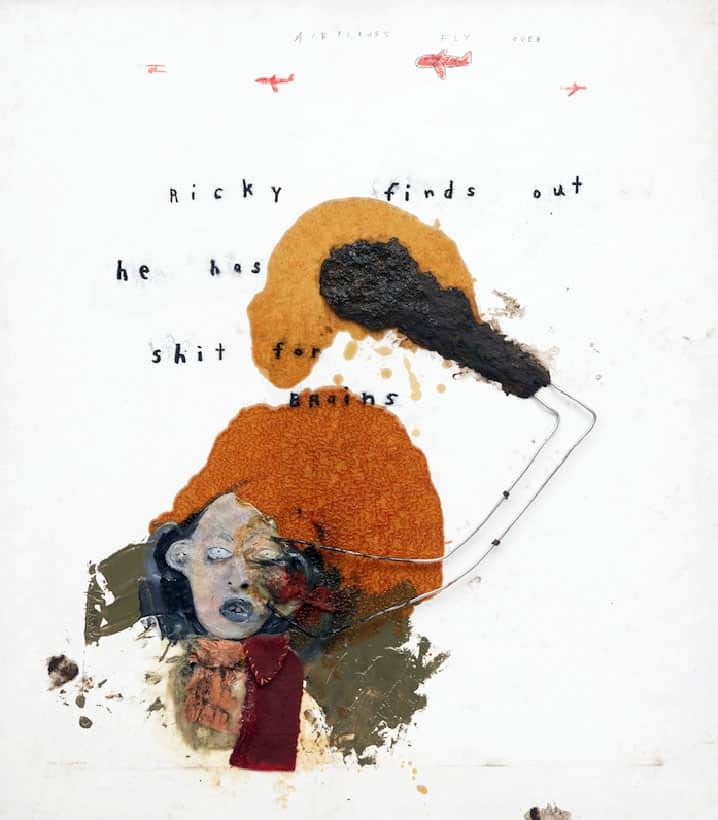

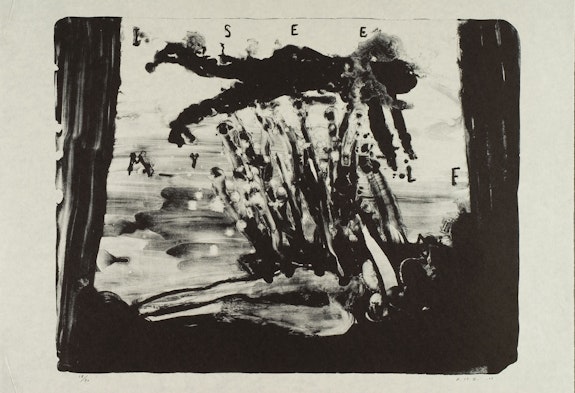

In the brain, disgust lights up next to lust and pleasure. In Lynch’s painting Rickey Finds Out He Has Shit For Brains (2017), there is a clear representation—or is it presentation?—of crap. Did he use Shinola shoe polish, or the real thing? Emily Colucci from Filthy Dreams thinks it could be real excrement, and this wouldn’t be the first time.

Religious Shit

Maybe Lynch is diagnosing an illness of society by examining and re/creating its abject excreta. Vedic texts connect feces to poison that must be excreted and examined. In ecology we know one group’s excrement is another group’s nutrient, and archaeologists love to find coprolites, as they tell us about what people ate, and therefore how they lived.

Tangentially, Hindu and Christian ascetics fast until their shit becomes “odorless and clean” (see Born Again Bodies). If you’re really good and healthy, your poop becomes clear. In early America, the human body was imagined to absorb the excrement and evil of the entire world “re-excreted, re-absorbed and re-secreted,” poop back and forth forever.

Dante described the people he encountered in the eighth circle of Hell as “dipped in excrement that seemed as it had flowed from human privies.” Poop is punishment. Martin Luther, the creator of the Protestant religion, described the devil he met as “black and filthy” and “permeated by a train of foul odor.” In Life Against Death, Norman Brown concludes that “the Devil is virtually recognized as a displaced materialization of Luther’s own anality.” Our monsters look like our crap, but we also meditate while on the toilet—it’s pretty funny that the revolutionary Protestant Ethic was revealed to Luther while he was pooping!

Milan Kundera says in The Unbearable Lightness of Being (2004) that shit is a more onerous theological problem than is evil, because somehow God’s perfect creation in his image defecates; the name Adam even comes from the Hebrew word for dirt, a symbol for shit. This is why the Angels got so pissed off when asked to bow-down to us: God’s favorite creature was made out of the lowest matter.

Poop/evil/Satan comes out of Heaven, is made out of Heaven. “The opposite of one profound truth is another profound truth.” Coincidentia oppositorum. Theologically, shit is a Zen koan, an irreconcilable paradox that can momentarily dissolve the mind into enlightened revelation.

Perhaps Lynch’s re/productions of crap and body parts can be compared to the artful models of guts and organs used by Roman soothsayers called haruspices, “entrail observers,” whose job was to read the future by examining the guts of sacrificial victims. There are also votive offerings, wax models of healed body parts that become gifts to the gods. In some cultures, models of the diseased or painful body parts are put in holy places like churches to remind the deity that the donor is still suffering.

I find it interesting that in Dialogue During a Picnic #2; as well as in the turd-mouth sculpture Lynch made for Jeffrey Beaumont’s bedroom wall in Blue Velvet, orality runs into fecality; four turds become word-bubbles. The title of the painting references eating and defecating, too, and the composition resembles part of an Animal Kit.

Kundera talks about a formative experience of seeing God illustrated in a children’s book as a man in the clouds, and how it implies his eating and defecating. Similarly, when Carl Jung was 12, just the thought of God pooping induced “pure grace and unutterable bliss.” This happened while he was repeating to himself, “Don’t think of it! Don’t think of it!”

We’re haunted by it, this putrid demon living/dying/rotting inside each and every one of us. Poop is poison, and yet, in some myth-histories, it’s also related to creation, to art, and to gold. In the Nahua (Aztec) language, for example, the name for gold is “God’s excrement” or the “excrement of the Sun.” The Bible says gold was made with us, from the beginning: in Eden, before we knew good from evil, we were adorned with precious gems “mounted in gold.” Can the fecal biofilm that covers and protects our bodies be considered gold?

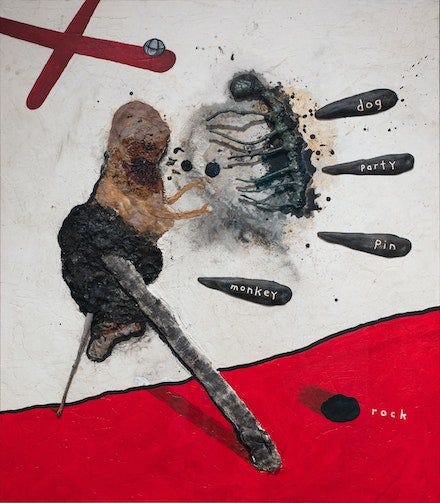

Like a religious icon, David Lynch’s large 1996 painting Rock with Seven Eyes presents a dark corny turd surrounded by garmonbozia-gold. Lynch: “Ochre, I love, love yellow ochre.” Do these seven eyes look forward to the seven turds in Mulholland Drive? I see the burnt placental tulpa orbs and golden “seeds” from Twin Peaks: The Return. Catherine Lanterman: “My Log is turning gold.” It could be the ufo-like liquid gold mirror-mind floating in the center of the Trinity Bomb in Part 8. Lynch’s strange painting may also be an unconscious homage to the art of Alfred Otto Wolfgang Schulze (a.k.a. Wols), whose photographs from the 1930s look like stills from Eraserhead. Tachisme, Europe’s version of Abstract Expressionism, means “stain.”

“Everything I’ve done, including my films, photography, and other things,

has found its form through painting.”

– David Lynch

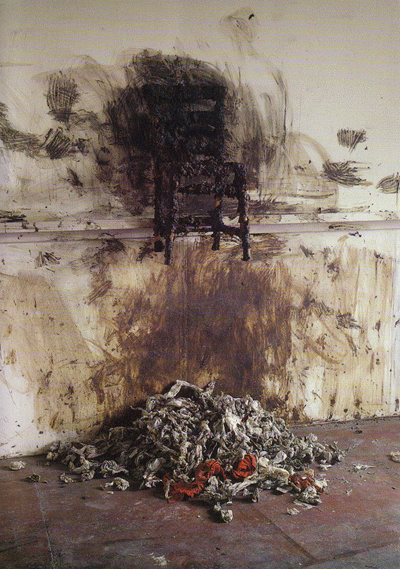

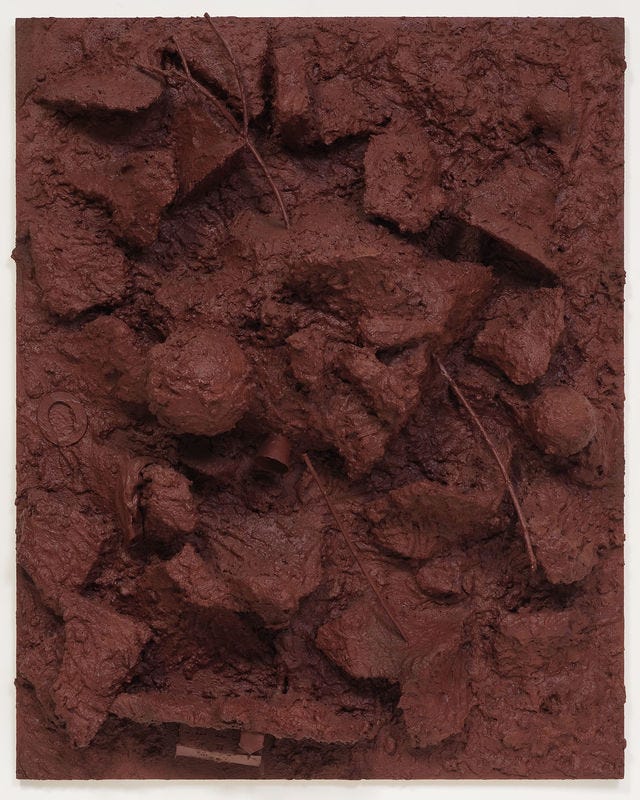

Painting, the whole process of it—squeezing colored mud out of a tube and wiping it onto surfaces—is scatalogical. Art-making in general is likened to consuming, digesting, and defecating or regurgitating ideas. Donald Kuspit: “To paint is to stick the extra finger of the physical paintbrush up one’s psychic anus, forcing one’s body ego to excrete a painting.” Kuspit thinks that most shit artists today have become an “unreflective asshole,” and art has been dumbed down “(already in Pop art) to mindless shit, that most leveling and un-ideal of all substances.” Yet shit art can also reach hieroglyphic, mythopoeic, even transcendental levels. In his essay “The Fig Leaf was Brown,” John Miller gives us his reasons for using materials that evoke feces: “For an artist deliberately to incorporate fecality in her or his work then is to make art about art via a psychoanalytic detour. Ironically, the detour may be more significant than the self-referentialism; it at least shows selfhood to be a construct.” Someone manufactured you. Miller is known for his chocolatey low-relief paintings from the ’80s built up from a thick impasto, “an analogy to the infantile urge to handle feces.”

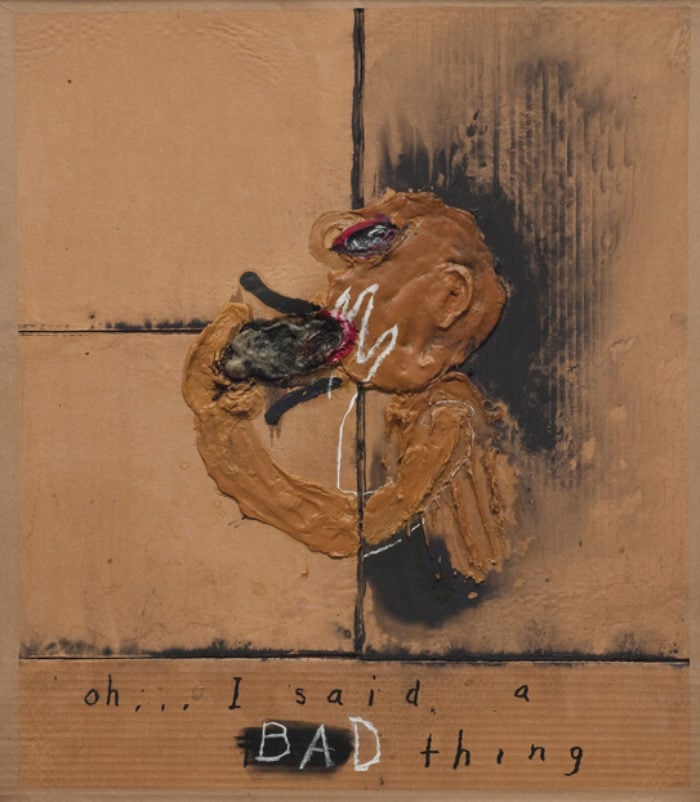

In Oh…I said a BAD thing (2009), a person made of what looks like smeared shit vomits (or eats) a smaller person made of darker shit. The painting is on untreated cardboard and is slowly deteriorating. Some of Lynch’s paintings grow fungus, or they crack and break, and he has to return to the galleries and fix them.

Most of the low-relief paintings in Lynch’s 2019 exhibition “Squeaky Flies in the Mud” (two more shit images) look like they’re smeared with it. “But, this texture and color scheme doesn’t gesture to some inner American darkness or a critique of its vacuity,” writes Colucci. “Instead, you get the sense that Lynch finds this earthy tactility utterly beautiful.” We can recall one of Lynch’s first memories as explored in his autobiography, Room to Dream:

We moved to Sandpoint, Idaho, right after I was born, and the only thing I remember about Sandpoint is sitting in this mud puddle with little Dicky Smith. It was like a hole under a tree they filled with water from the hose, and I remember squeezing mud in that puddle and it was heaven.

Surrealists like Lynch, according to Andre Breton, are after ultimate reality or surreality, which is full of contradictions. They love to reverse roles to help us think about things in new ways—“subversion by inversion.” They’ll change the race or sex of a famous historic figure, or put teeth where they don’t belong. Like an episode of The Twilight Zone, they’ll offer us whole alternative timelines where food is shameful and poop is public—for instance, this scene from The Phantom of Liberty (1974) by Luis Buñuel, where a family and their guests all sit on toilets around a table to read, chat, and poop together. When someone gets hungry, they ask to be excused, find the small, private closet down the hall, get inside, close the door, and eat alone, somewhat humiliated.

Other People’s Shit

There are five important shit artists whose work helps us better understand what Lynch is doing: Piero Manzoni, Chris Ofili, Silmoodawa, Wim Delvoye, and Tala Madani. They will lead us into an architectonic space filled with psychological, alchemical, spiritual and material theories of shit.

Firstly, Piero Manzoni famously canned and sold his own feces in 1961 as a way to, as he put it, “tap mythological sources and to realize authentic and universal values.” His 90 cans of Merda d’artista/Artist’s Shit also challenged the idea that everything an artist makes is art. I love how his project echoes into the artworld today: Someone who goes by the name of White Male Artist makes $HT Coins, NFTs, where they eat the diet of a famous artist and then can their own derivative Artist’s Shit.

For our study of Lynch, pay attention to how Manzoni intentionally connected shit to gold: his cans were to be sold by weight (exactly 30 grams) based on the current price of gold. Now they’re sold for hundreds of thousands of dollars each. They’re one of the 10 most expensive feces in the world. (And yet, do Manzoni’s cans even contain feces? How would we know? We’d have to ruin the sculpture to find out. Manzoni the trickster sold a story, and we may never know: Schrödinger’s Scat. Does it really matter? One of Manzoni’s cans was opened, and that one was filled with plaster).

Plaster or poop, he turned it into gold.

It’s not that original. “Golden poop” and golden eggs are in our fiction, and there is mythological, anthropological and psychological literature that associates gold with feces. Freud:

The contrast between the most precious substance known to men and the most worthless, which they reject as waste matter, has led to this specific identification of gold with feces.

It’s a fact that dragons poop gold. In Germany there are statues of a Dukatenkacker (“Ducat Shitter”) who shits gold coins, and there are traditional New Years Geldscheisser figurines used for good luck. There is a man pooping coins in The Garden Of Earthly Delights. Golden poop is a cute character in Japan called Kin-no-Unko, sitting pyramidal on a red cushion like a Buddha. A man’s excrement literally turns into gold in the film Holy Mountain, and this all bespeaks the old alchemical idea of turning the shit of life into gold. Artists dress up life to make bare facts become existential truths. It’s an alchemical process that charges things with significance and agency. Andre Breton wrote that Marcel Duchamp accomplished this alchemical act with the readymade: “an ordinary object elevated to the dignity of a work of art by the mere choice of an artist.” The trash gets anointed, placed into the “art world” (Danto), where it acquires an “aura” (Benjamin), and value. Waste turns into art. (Shit turns into gold).

Gerald Silk (1993) remarks that Manzoni had the Midas touch. But alchemy didn’t just take place in our abstractions and metaphors. The daily work of alchemists took place in studio laboratories, where they manipulated physical materials: “Alchemists ritualistically and experimentally used body products such as excrement, urine, blood, and breath, believing them to be sacred, thaumaturgic substances.” Manzoni also made pieces involving his breath, and proposed works that included his blood.

Jacques Lizene used his own shit as paint in the ’70s and ’80s. He’d eat pigments and colorful foods, and then collect his shit in jars. Sometimes the paper with which he wiped his ass became the work of art. Vomit artists use a similar method, eating pigments and then vomiting them onto paper. This makes me think of Paul McCarthy’s life-size tubes of paint he fists in Painter (1995). McCarthy’s video ends with a scene in which art collectors line up to sniff the painter’s ass, probably as a nod to Manzoni.

Verrips connects Mazoni’s Artist’s Shit—along with other shit-art—to neo-capitalism and how “the consumption of fertilizer and feces, commodities and capital, goods and garbage are closely united.” In Barbie (2023), Stereotypical Barbie thinks of death shortly after seeing the trash collectors. Maybe this is why Weird Barbie declares her interest in overseeing sanitation: people literally flush millions of dollars in gold down the toilet every year.

Next is Chris Ofili and his large painting The Holy Virgin Mary (1996), where a black woman with big red lips is surrounded by a golden-yellow background spangled in cut-out pictures of twerking asses, and, “Instead of being pinned upon the wall like it’s being crucified,” Ofili says, it’s leaning on the wall, resting on two small pedestals made of elephant dung. The subject’s right breast is also made of dung. In his series The Upper Room (1999–2002), lumps of glazed dung stick out of rows of large colorful canvases like doorknobs. Rhyming with Lynch, Ofili says he wants to bring together “the beauty and decorativeness with the ugliness of the shit and make them exist in a “twilight zone.”

Almost two decades before Ofili, David Hammons made an entire book of elephant dung sculptures, and Swiss artist Dieter Roth created Shit Hare out of rabbit poop, dirt, and grass. Roth’s work, like Lynch’s, explores physical and mental decomposition, and here we also get an association between dirt, shit, and chocolate: Roth’s effigies resemble chocolate Easter bunnies. Is it about the bunny?

Fecal Weapons

“The aesthetics of the dung heap are the moral means against conformism,

materialism and stupidity.”

— Otto Muehl

Fecal art history connects to Native American history. Historian Ramsy Cook, in 1492 and All that: Making a Garden out of a Wilderness (1992), looks at 17th century French “wilderness enclosures” or human zoos built to display Indigenous people kidnaped from Acadia, now-Nova Scotia. (Cook interrupts the story to point out that the word “paradise” is from the Persian word for an enclosed park filled with animals). He relays the story of Silmoodawa, a Mi’kmaq gentleman captured and put into one of these zoos. People would pay to watch him hunt a deer with a bow and arrow, skin it, cook it, and then eat it. He would dress up and act a part, but one day it turned from theater to performance art when, after he finished eating, Silmoodawa walked over to where the spectators could clearly see him, squatted down, and took a shit. “Doing so,” explains curator Matthew Ryan Smith, “was an act of retribution, and presumably many of the onlookers could sense the hunter’s displeasure in the air.” For artist Rebecca Belmore, this early shit art “not only represents one of the first international performances by an Indigenous person, but it’s also a dissident gesture of anticolonial resistance.” (See Action and Agency, Advancing the Dialogue on Native Performing Art, 2010). We don’t know for sure if Silmoodawa really did this, it happened so long ago, but the story and its popularity matters.

Other Indigenous ‘scatalogical rites’ are reported, like the Zuni’s urine and feces dance, enacted specifically for settler audiences, parodying a Catholic mass. “When shit is used as a weapon, it is often considered as a subversive matter: a ‘means of non-violent resistance’, explains Florian Werner, “used preferably by those oppressed, excluded and unarmed in order to defend themselves against a presumed or real superior power.” Marielouise Jurreit calls it “alternative resistance.”

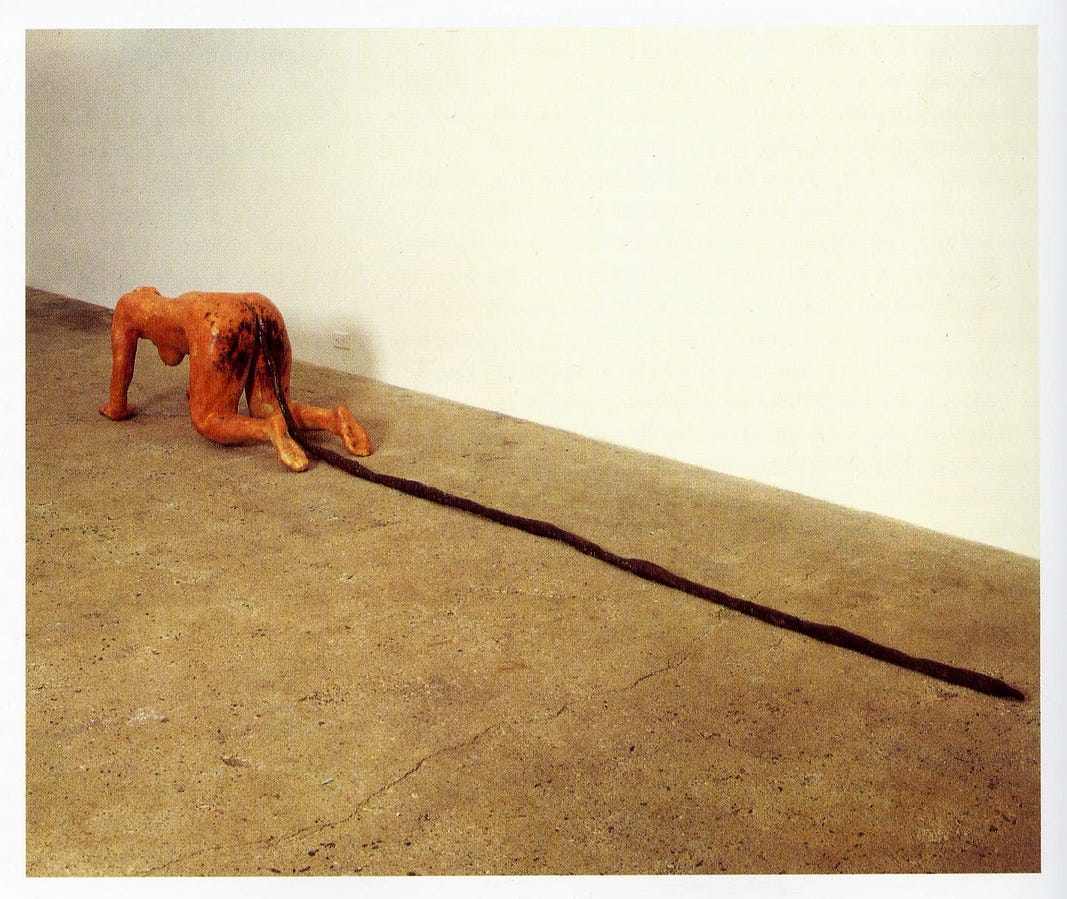

Silmoodawa’s artistic gesture of “alternative resistance” echoes through the centuries with works like “Shit Instead of Blood” (2014), in which Natali Cohen Vaxberg films herself pooping on flags from around the world “as a gesture against nationalism.” (She got arrested for this by Israeli officers.) Similarly, though for different reasons, Viennese actionists brought feces, sex, and blood into the gallery space in the 1960s and ’70s. Otto Muehl, one of the more controversial leaders of this (bowel) movement, says, “My vocabulary is shit, urine, sperm, sexuality, sodomy. I use all of this deliberately and employ it as an assault, as a way to attack moral taboos.” Mike Kelley’s Nostalgic Depiction of the Innocence of Childhood (1990) does the same with a sepia-toned photograph in which a naked man and woman squat over stuffed animals in sexual positions, the man rubbing shit against his ass with what looks like a stuffed bunny. The list goes on; see also Kiki Smith’s Tale (1992) and Robert Mapplethorpe’ Self Portrait with Whip (1978).

Where It All Began

Artists fill houses and art galleries with dirt as a stand-in for shit. Psychoanalysts with their theses on feces like to point out that during the ‘anal stage’ of our early physical and psycho-social development (age one to three), we learn to control our bowel movements, and this is how we start to explore the boundaries, openings and muscles of our bodies. It’s also when we learn to feel intense humiliation and shame in order to conform to the demands of the (m)Other. In Cultivating the Heart of Compassion, Ram Dass jokes about how our parents wanted to love us unconditionally, but they also had to socialize us, “and they would tighten up if you, ya know, shit on the living room floor… We learn early on what not to do to make it work.”

We abject (part of) ourselves, and this causes a foundational boundary to form in our self image. However, the repressed physical and psychological material eventually gets out. All boundaries becomes cracks in the end.

Meanwhile, we (not always so) secretly hate the world for making us hate our figurative and literal shit. This is directly addressed in the early 1980s by the British couple Gilbert and George, whose cartoonish painting Shit Faith (1982) shows four turds coming out of four butts facing each other to create a crucifix. (It looks like Sue William’s 1991 drawing Try to Be More Accommodating of four hard cocks stabbing into a woman’s face). Then in the 1990s, Gilbert and George created the exhibition The Naked Shit, which included large-scale pictures of themselves naked with cartoonish, human-sized turds floating all around, filling the walls of the gallery like stained-glass windows.

We make a history of two thousand years of civilization and morals look like shit, because it tried to inculcate into us that nakedness and feces are bad.

“We are naked, full of shit — and that is what we want to show.” “It is just a convention [to hate shit], and we wish to be as artists unconventional.” It made people angry. “Our art is capable of bringing out the bigot inside the liberal, and the liberal inside the bigot.”

Prophetic Shit

Art is a report on the now that anticipates and precipitates advances in technology, science, and religion. (See Leonard Shlain’s Art and Physics or Thompson and Abraham’s The Geometry of Angels.) What is Lynch’s excremental art anticipating? Maybe simply that the future is not going to be cleaner, but grosser. After looking into all the interdisciplinary data available, futurist and artist Michael Garfield concludes that the future is disgusting—and that isn’t necessarily a bad thing! Disgust is a predictable response to the novel strangeness of our interconnectedness and vulnerability to forces we cannot fully know or control. But imagine, says Garfield, “a house that…eats the air and shits my dinner, brews me beer and psychedelics in a bubbling alcove, calls me by my secret name.” Could be much worse!

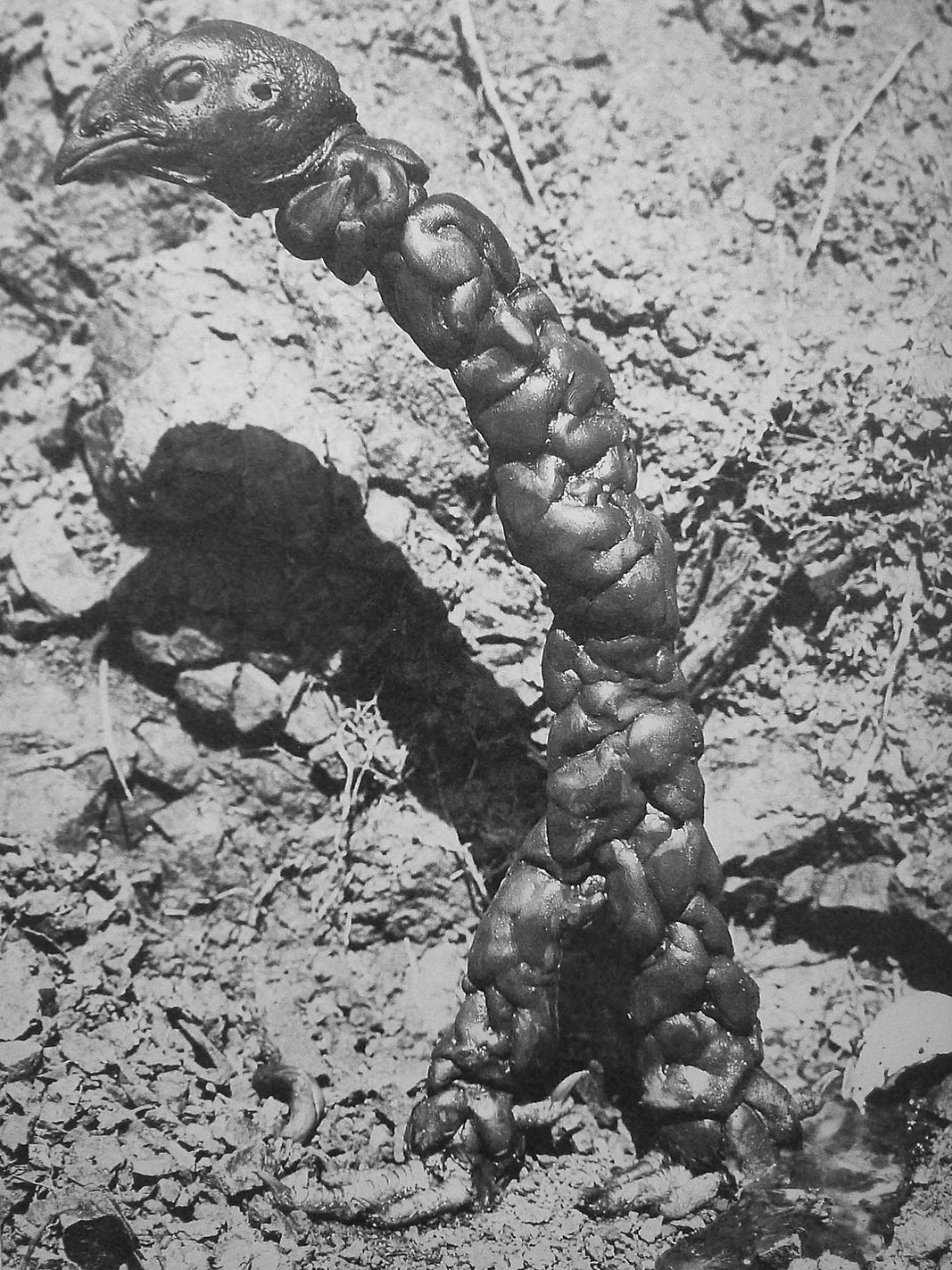

Nissim Gal (2023) looks at scatological art in Israel as work that “seeks to consider humankind as machines that produce waste.” Are we machines? Belgian artist Wim Delvoye creates biological machines appropriately called Cloaca that physically turn fast food into feces that is collected, packaged and sold as art. The installation articulates a pattern: taking a ubiquitous

behind-the-scenes actor and spotlighting them, demonstrating Marshall McLuhan’s adage that “the previous environment becomes a work of art for the new invisible environment.” In some exhibitions, Cloaca is installed next to stained-glass windows, and we get the sense of shit-machines existing with God—just like we see in the traditional caganer figurines in Spain, “the most important part of the nativity”: a person shitting, which complicates our understanding of divine incarnation and Christmas. (Holy shit! The grotesque, rather than being a negation of the sacred, may actually be an intensification of the sacred, for what could be more grotesque than the crucifixion of Jesus Christ). As I mentioned before, shit blends with church in the reported excrement-eating rituals of the Zuni, described as “an outlandish yet faithful mockery of a Mexican Catholic congregation at vespers.” Naked clowns parody Catholic mass before doing all kinds of other nasty shit. See also the first episode of Season 3 of How To with John Wilson. Wilson finds a clean New York City public bathroom covered in Christmas decorations, which turn everyone into caganer figurines.

“Each of these Cybershits are unique pieces of art,” says Cloaca’s exhibition description. At first they sold for $1,000 each, but now they go for more. Notice how Cloaca’s logo looks like a combination of Coca-Cola and Ford, which leads the imagination into factory lines, conveyer belts, and machines that are capable of duplicating human activities. Delvoye’s signature looks like Disney’s.

Mechanical Shit

Delvoye says Cloaca explores issues around bio-engineering and the cyborgization of the human body. This makes shit art a perfect example of William Irwin Thompson’s prediction, that the defining element of our new culture will be a symbiosis between art, science, “and the dark and fluid movement of all we choose to ignore as pollution and excrement.” Thompson looks at John Todd and his New Alchemy Institute as an example, who had the “instinctive genius to create living machines.” Related, horse shit is used in machines created by the Tissue, Culture & Art Project, established in 1996 by Oron Catts & Ionat Zurr. The artist-scientists explain,

In times of ecological crisis, there is a vital need for seriously playful artistic interventions.

Part of the work is called Sunlight Soil Shit (De)Cycle (3SDC), described as “a messy, biological device” or assemblage of different species: it uses a compost system as incubator to provide the necessary heat to maintain a small flask of disembodied mouse cells. The structure looks like a bomb shelter placed in the middle of an empty room. It also looks like a temple.

There are artists who collect the excrement of entire cities and turn them into monuments, as we see in Mike Bouchet’s The Zurich Load (2016) and Santiago Sierra’s Anthropometric Modules Made from Human Faeces by the People of Sulabh International, India (1997). This is gold for future archaeologists. Similarly, Grethell Rasua is a Cuban artist who works with other people’s shit. In one project she paints a house using varnish made with the poop of the family who lives there. Tangentially, Picasso used some of his daughter’s poop to draw an apple in a still life 1938, and he liked to talk with his surrealist colleagues about using dried excrement in art. He’d speak excitedly about the different textures of poop so often that we might call him a “coprophiliac.”

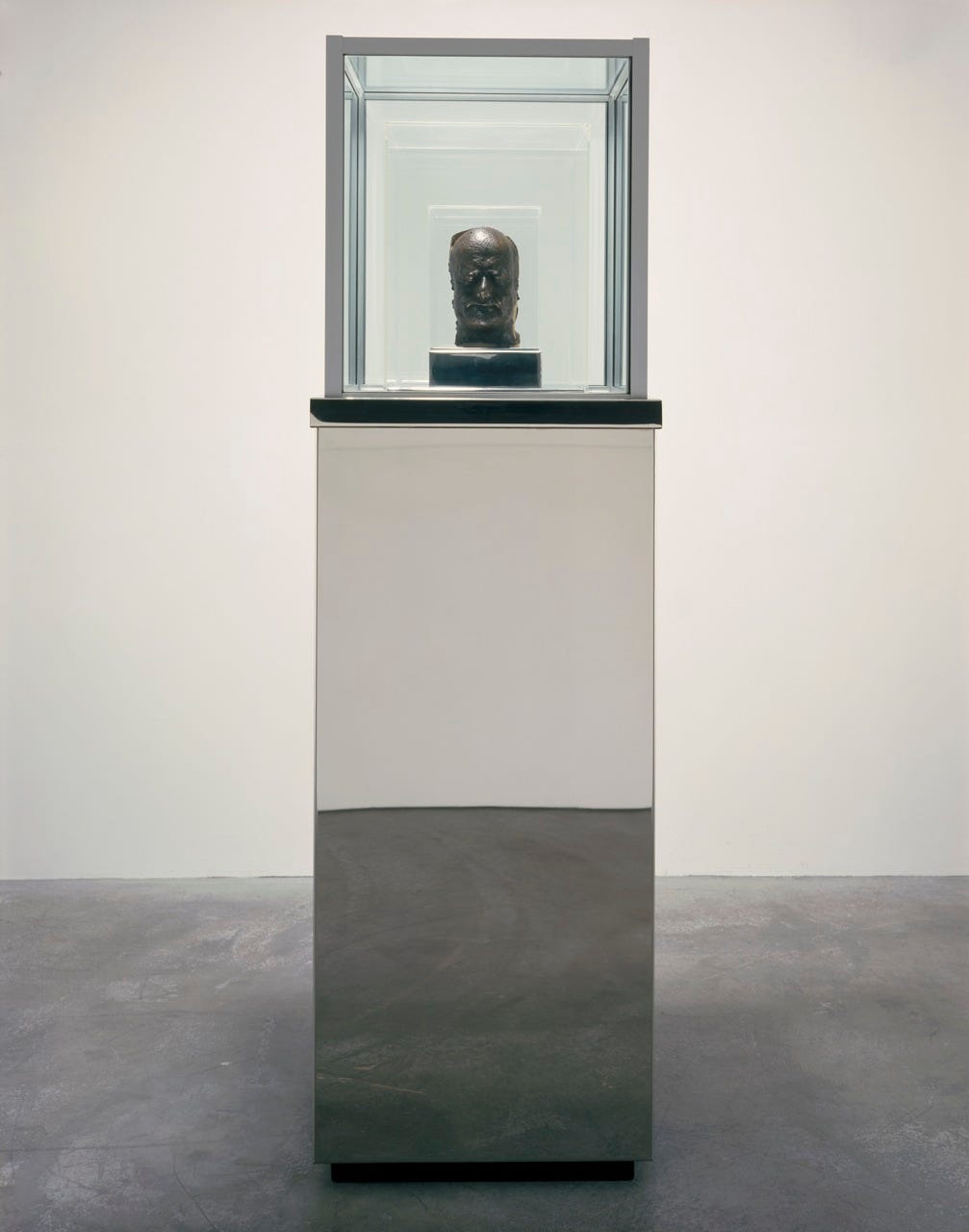

There are people who use their own shit as material for self-portraits, and can we blame them? Marc Quinn created Shit Head (1997) and placed it inside layers of glass boxes. Twin Peaks. Andres Serrano, famous for his 1987 Piss Christ, photographed his crap zoomed way in and called it “self-portrait” (2008). Art critic and philosopher Donald Kuspit wrote a brutal critique of Serrano and McCarthy’s shit art. In his eyes, “their shit symbolizes the comic tragedy that art has become and the tragic comedy that America has become.” Terence Koh, at Art Basel, 2007, presented gold-plated pieces of what he claimed was his own shit. They sold for $500,000. People in New York City spray paint dog shit on the sidewalk gold, and sometimes throw glitter on it.

Climate Control

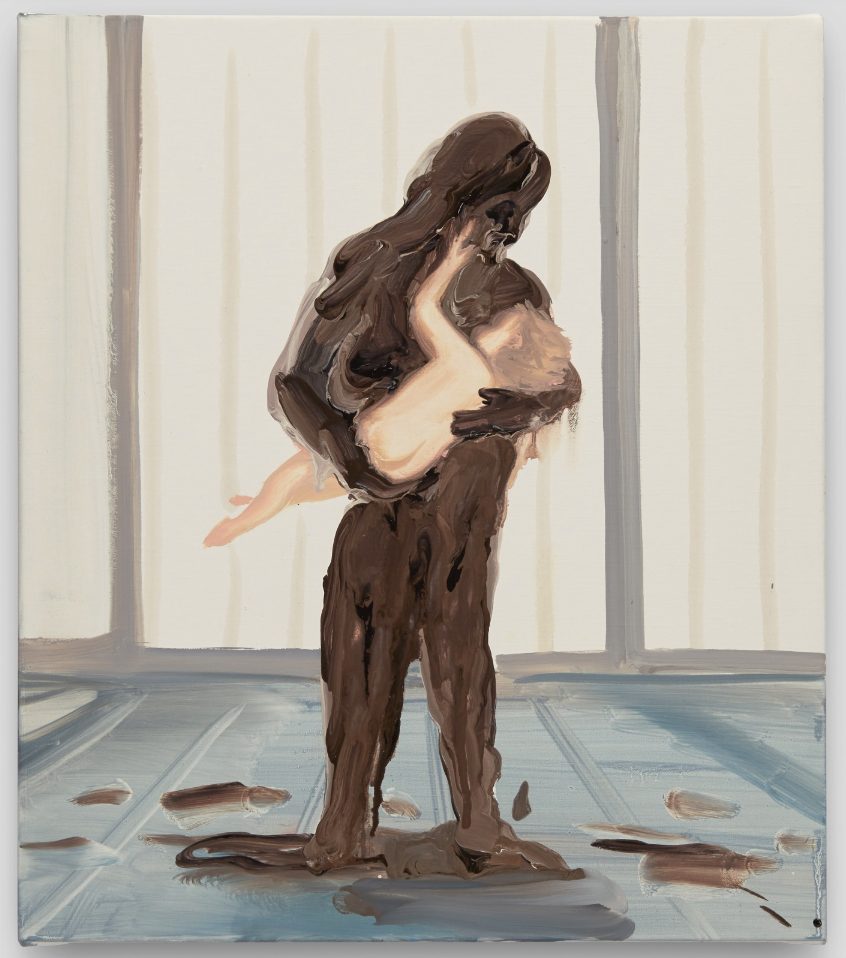

Poop is laden with power, horror, and humor. In Tala Madani’s short animated film Shit Mom, we follow a mother, made of what looks like wet excrement, who leaves her brown residue throughout her decadent house. The soundscape consists of birds chirping and her body squishing. It’s very Lynchian. Madani also likes to paint ghosts and ceiling fans. I love her work. Another Madani short film is called The Womb (2019) about a human fetus who grows up with a placental television. The fetus tries to turn it off with a remote control, but it keeps turning on, showing all the hits—including images of war and the bomb. Finally the little fetus takes out a gun and (SPOILER) shoots holes through the TV/wall of the womb. They can finally see the natural light outside, but not for long…

Many of Madani’s oil paintings depict infants playing with a literal shit-mother, and this could be “a deliberate desecration of the iconic image of mother and child,” according to one critic, but it’s also communicating feelings many mothers all over the world understand deeply: the perception of them as shitty, and of women in general as dirty. (See Change The Fucking Channel Fuckface above for Lynch’s version). This reminds me of Klaus Theweleit’s Male Fantasies: Women, Floods, Bodies, History (1987), that explores dirt and swamps as metaphors for women in Nazi art and literature.

Shit is universal, but our reaction to it is not. The experience of shit is probably culturally situated, sexed and gendered, as male bodies are dealing with a different type of horror when it comes to the body’s excreta. To contain their fears of being permeable and therefore feminized, manly men imagine themselves as closed, dry and clean, the opposite of the female sex.

This isn’t good. Bjorn Krondorfer articulates the problem in Men’s Bodies, Men’s Gods (1996): “a closed body isolates and imprisons man, and dries him up spiritually.” To remain clean and virtuous is to remain irresponsible and uncaring. The antidote to this toxic masculinity and toxic spirituality is to look at our shit, figuratively, literally, and allegorically. Slam the brakes and let the stuff in the back seat fly into the front where it can be examined and integrated, as William Irwin Thompson put it. We need to make the darkness conscious. The authors of Poop Worlds, Shaka McGlotten and Scott Webel, conclude:

It is closer to food than abject waste, and it embodies sunlight, power, shared madness, at once vulgar and innocent. It is matter inside out, our collective shame and untapped fortune. It is inside you right now, waiting to be recuperated.

The great scatalogical artist Mier Lee: “I think that these works are particularly well suited to the many points in life when things stop making sense and collapse in on themselves.”

John Miller’s chocolatey paintings look like obscured platonic shapes, akin to Louise Nevelson’s Sky Cathedral (1958) and Anish Kapoor’s As if to celebrate (1981),or Kapoor’s Apocalypse and Millennium (2013) made of dirt and resin. Dismemberment of Jeanne d’Arc (2009) looks like huge red turds. Kapoor, a great Buddhist philosopher and artist, literally extrudes clay to look like feces in Between Shit and Architecture (2011). What is he getting at?

Florian Werner, from Dark Matter: The History of Shit:

Human culture is built on shit. Not only because our cities, the paradigmatic example of our modern civilization, are built above gigantic sewage systems. Not only because our metabolism and with it our life itself would be impossible without the excretion of shit. But also because it is only when we draw a line of separation from shit, we come to know what culture is. Without shadows, there is no light, without dirt, no cleanliness.

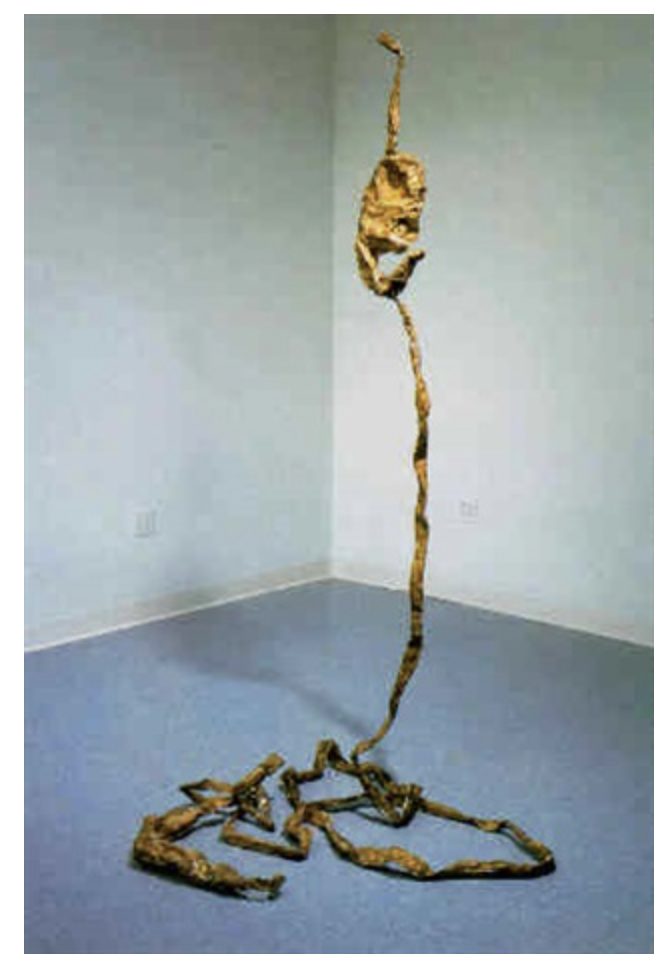

In 1978, Kiki Smith started focusing on guts and shit specifically, culminating in Tale (1992), and as the interviewer and author for ArtForm puts it, Smith’s abject art is for healing, “in a spiritual or social rather than a medical sense.” Smith also makes bones, organs, and frogs out of glass, probably an extension of those ex-voto offerings.

Liu Wei, Indigestion II, mixed media (2004)

A close-up of Jiu Wei’s Indigestion II reveals hundreds of toy soldiers. Jung: “One does not become enlightened by imagining figures of light, but by making the darkness conscious.”

Conclusions

I consumed as much fecal art and theory as I could, and then this essay just kind of exploded out of me! Shit art is a type of ‘anti-art’ and ‘abject art’ and weapon with histories. Engagement with it quickly leads into Freudian, Jungian, Alchemical, Vedic, Materialist, Gendered, and Indigenous territories.

It’s a shortcut to disgust, an aversion emotion that’s behind everything and can explain everything. I’ve argued Lynch’s fecal art is also unsettling—as in decolonizing, because it’s trickster and taboo, and it may even be the fastest and most effortless way to transcend.

While feces in art has a long history, Twin Peaks fans should get excited: anthropologist Jojada Verrips (2017) notes that it’s around 1945 when shit art really hits the fan. This sudden increase relates to cultural, political, and economic forces, asserts Verrips, but we can pinpoint it to the intensification of evil and time initiated by the Trinity Bomb.

Our psyches and societies are built on crap. Florian Werner: “Shit is indispensable to our self-understanding as modern people.” It accompanies us throughout our whole life in our blind spot, alongside a constant policing of our orifices and excretions and identities. We are so ashamed that our bodies produce such a putrid substance, that we “shadow project,” and our fictional monsters look like our poop. (Bear in mind that the word monster comes from the Latin monstrare, meaning to demonstrate and to warn…)

Shit art is ancient yet current, and by plumbing this tradition, or just by scrolling through images of it online, we see aspects of ourselves. Teeming with beings exchanging information, the matter in our gut is our “second brain,” and an integral part of our future. Simultaneously, shit is the paragon of the rejected, repressed, and dissociated part of the self—which is probably why artists like to force us to reflect on it the way saints reflect on the skull, or Buddhist monks reflect on the human corpse.

Temporary surrender to the gross, uncivilized and “wild” enables one to get to know the other within oneself. By trespassing taboos, through the help of artists, we come into contact with aspects or dimensions of ourselves that have become alienated to us. Meditation alone can’t do this, because you can’t see the repressed material from the inside first-person witnessing awareness. Ken Wilber argues that “researchers have known for decades that meditation won’t cure shadow issues and often inflames them.” You’ve got to reach out to others and the “Other.”

In a sense, looking at David Lynch’s shit art is an expedition towards repressed aspects of the self, an expedition that might have a correcting effect on the self-image. Shit and shit art is a toxicology report, a cultural artifact, a mirror, and a nutrient. The art is telling us to get dirty, and to get ready for a much better understanding of ‘reclaiming the shadow,’ ‘waste management,’ and ‘poop friends.’ As prophesy, it’s saying we will have to profoundly deal with our shadow, taste the waste, turn it to “gold,” or be doomed.