There are a lot of different kinds of Twin Peaks fans, but one thing that’s pretty ubiquitous among them is a desire to keep expanding this place we love. Clues and patterns in the episodes/parts are identified, analyzed, synthesized, and debated; interviews with makers are conducted, published, and devoured; paratexts are re-read and mined both for the additions they make and the incongruities they introduce; fan phenomena are joined, documented, and shared.

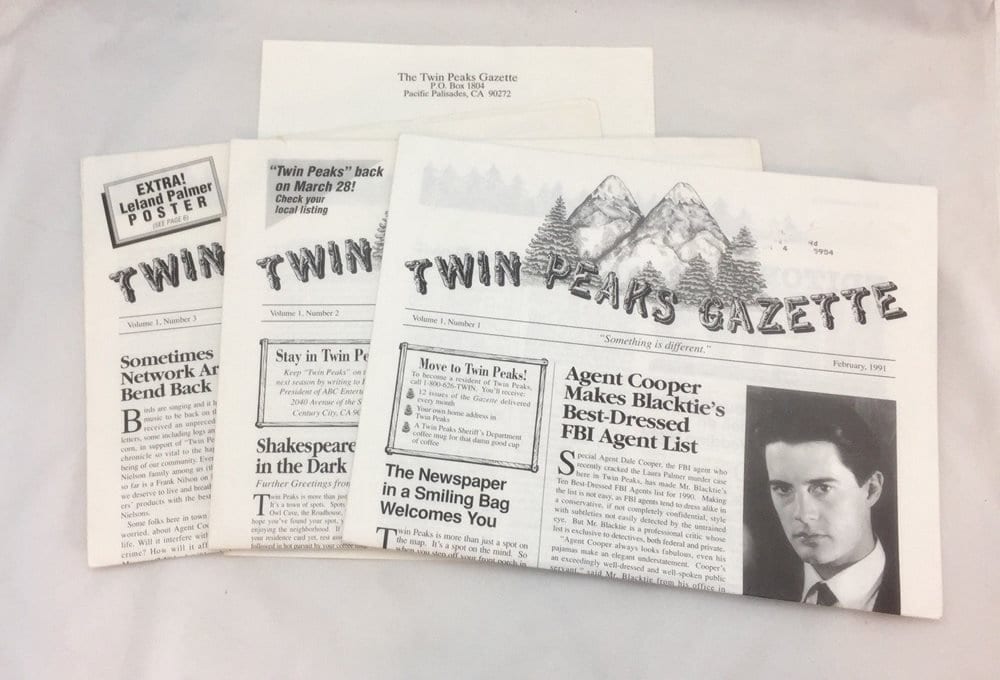

For me, as someone who’s both a fan and a researcher, it can seem like there’s not a lot of Twin Peaks territory that hasn’t been at least located if not also examined. But then one day I was looking at the three issues of the Twin Peaks Gazette, the short-lived fanzine from 1990-1991, and I got to wondering about newspapers.

Specifically, I wondered what the local newspaper coverage of Twin Peaks was like in the small Washington towns where the series was filmed. Because I grew up in a small town (in my case Decorah, Iowa with a zip code eerily similar to the population the network pressed Frost and Lynch into assigning the Twin Peaks: 52101/51201) I know that the local newspaper is like a community seismograph that registers reactions to major events—like a major television production coming to town. I got to thinking that the local newspaper in the Snoqualmie and North Bend area would likely contain some sort of record of hometown journalists reporting on the production, of letters to the editor voicing opinions on the series, and perhaps of advertisements aimed at leveraging the sudden stardom of the towns to boost business.

I started digging online and was not surprised to find that the digital archives of the Snoqualmie Valley Record don’t go back thoroughly to when it all began. But like Dr. Amp, I gripped the golden shovel of research and kept digging. That’s when I learned that the Snoqualmie Valley Historical Museum maintains a complete archive of the local newspapers—among a myriad of other fascinating objects and documents that provide a robust history of the people and place for whom and which Twin Peaks is only a drop in the ocean of their past, present, and future.

On a recent work trip to Seattle, I built in time to visit the museum, and the administrators there were extremely kind and helpful—heartfelt thanks, Cristy and Gardiner! In the museum, I flipped carefully through the massive binders that hold a year’s worth of newspapers each.

In this series of articles, I’ll share, chronologically, some of the findings that expand and add texture to Twin Peaks. Today it’s an entry from 1989.

The earliest reporting I found in the Valley Record was an article by Paul Weideman titled “‘Northwest Passage’ Turns Valley Into A Movie Set” and published on March 2, 1989. The article offers a few intriguing things.

First, even though many fans including myself know very well that the series was originally called Northwest Passage, it can’t help but seem strange to read this in black and white print outside the milieu of show producers and makers. There’s a taste of alternate timelines to the experience, an uncanny reminder that the text as we know it was open to lots of different possible incarnations, even though once something is published it can feel as if that was its inevitable form. And speaking of alternate timelines, the producer told the reporter that they anticipated a series premiere in September of 1989. It’s fascinating to imagine how a Fall pilot premiere in September might have altered Twin Peaks. Had episodes aired in juxtaposition with the fall of the Berlin Wall, for instance, how would that real-time historical dynamic have inflected viewers’ experiences? Would the increase in daytime darkness for Northern Hemisphere viewers have shaped responses differently from the rejuvenating energies of April? Or, more mundanely yet no less fundamentally, what would a different slate of advertisements have done to the tone of each episode?

Second, the article documents the mixed reactions of local residents to the production process. Weideman describes the thrills of having big-name actors in town and of the prospect of familiar fellow citizens and businesses and landmarks being immortalized. Special emphasis also goes to the students in Debbie Navarre’s drama class who got the amazing opportunity to act on camera alongside notables like Piper Laurie, Richard Beymer, and Kyle MacLachlan. Yet Weideman also remarks, “But there’s bound to be a negative impression or two left by the invaders from, really, another culture.” Several business owners interviewed were nonplussed by having the main street shut down for filming, particularly as both the money and potential fame were unevenly distributed along the lane. While the Mar-T cafe, transformed into the RR Diner, was poised to reap rewards, other shops saw the temporary shutdown chiefly as lost revenues. Still other business owners reported feeling fast-talk pressured into signing agreements they felt gave away too much future rights to the use of their venues’ images.

This mixed reaction is, it seems, to be expected. And in my multiple sojourns to the North Bend & Snoqualmie area that span from 1993 to 2019 this complicated dynamic persists. Uneven distribution of the benefits Twin Peaks catalyzed for the valley seems destined to foster antagonism and in a way that resonates with the uneven distribution of land speculation at work in the series. But another factor is a history of multiple traumas to the valley’s economy.

One trauma unfolded in the 1950s when Interstate 90 was designated to cross Snoqualmie Pass. Before that North Bend and Snoqualmie were on what was referred to as the Sunset Highway that was basically constructed on the route of a mid-nineteenth century wagon trail. As small towns on the primary transit infrastructure, North Bend and Snoqualmie were home to businesses that serviced travelers and were points of circulation for farm and lumber harvests. But when I-90 offered a more efficient infrastructural line parallel to the Sunset Highway, the economies were traumatized and had to recover through reinvention. This 1950s trauma presents a non-fictional historical context that enriches the 1950s vibe that Lynch and Frost infused the series with.

The other major trauma was the decline and eventual closure of the Weyerhaeuser Mill. In 1989 as the Pilot was being filmed, people were losing work. The Valley had been a place where residents might finish high school and then find solid, steady employment at the Mill, but with the dual pressures of corporate drives for maximum profits and rising environmental awareness and regulation, the topography of employment was rapidly shifting, requiring adaptation. Surely this traumatic eruption of class antagonism intersecting with ecological consciousness and action contributed to the frustrations of residents who felt left behind and/or exploited by the production.

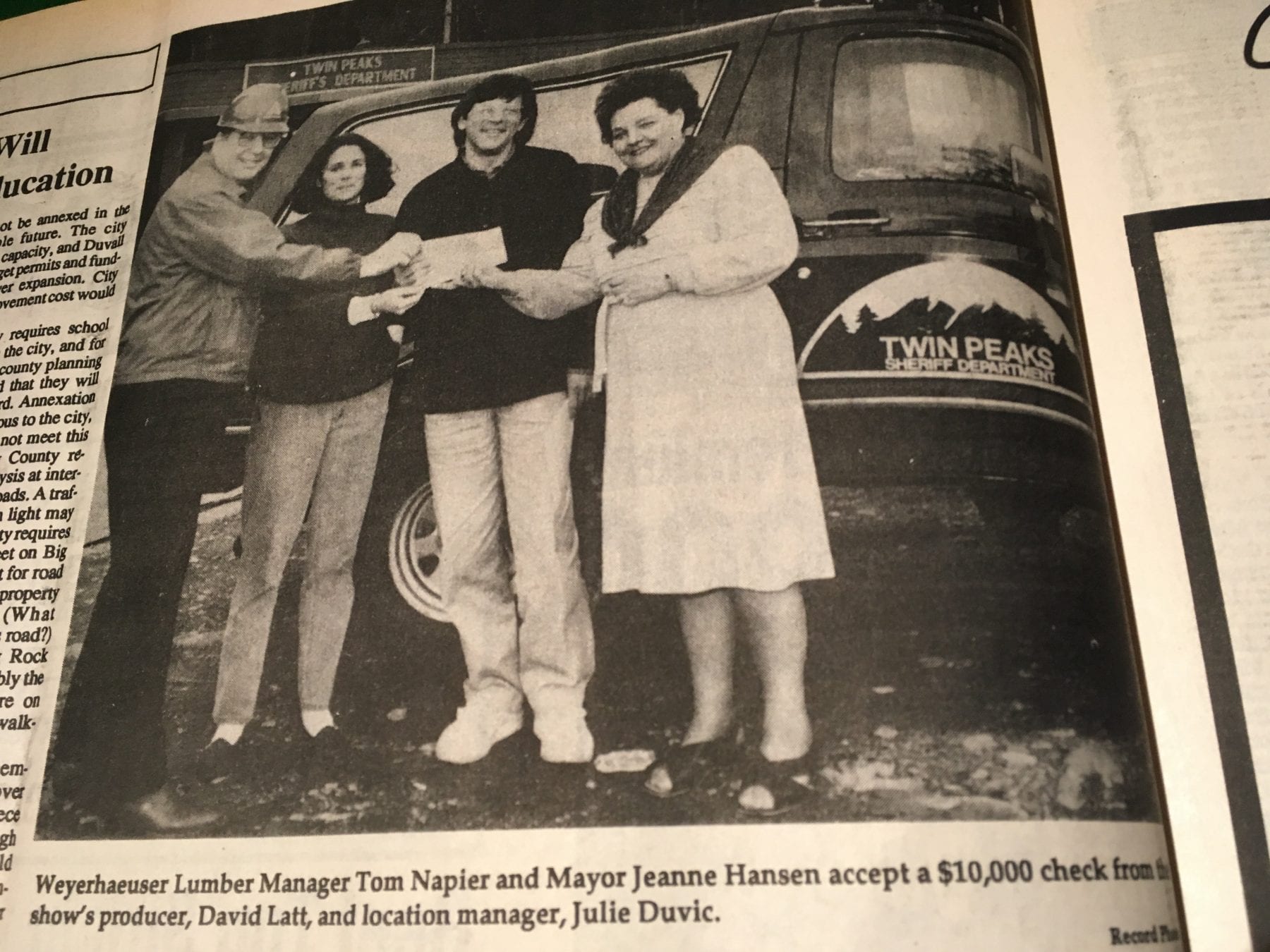

Third, Weideman pivots again to the positive by noting that the production paid $10,000 to Weyerhaeuser for use of the sawmill and the company turned right around and donated the money to Snoqualmie to build a shelter for the Centennial log that we see featured in the opening credits of the Pilot episode. Accompanying the article is a nice photo of Weyerhaeuser Lumber Manager Tom Napier and Mayor Jeanne Hansen accepting the check from producer David Latt and location manager Julie Duvic in front of the Twin Peaks Sheriff Department.

On a final note, just as Agent Cooper thinks to scan beyond the primary photo of relevance on the page of Flesh World and notices the image of Leo’s truck, I explored the other pages of the March 2, 1989 newspaper and was struck by the full-page headline story about a mill fire in Preston that occurred only about a month after the plywood mill at Weyerhaeuser had gone up in flames. The future of the Valley’s economy and employment are registered in the large print of the headline, the details of the article, and the photo of the devastated mill. Even as Twin Peaks was never marketed or otherwise presented as a documentation of a region and/or way of life that would warrant critical assessment of its accuracies, there’s something to the coexistence of this front-page story and the first report of filming the series that sparks a sense of the doppelganger, the double. I would argue that it can be exciting and illuminating to listen to the sounds that the frisson of the series and the real people and place of North Bend and Snoqualmie produce when they’re plugged into each other.

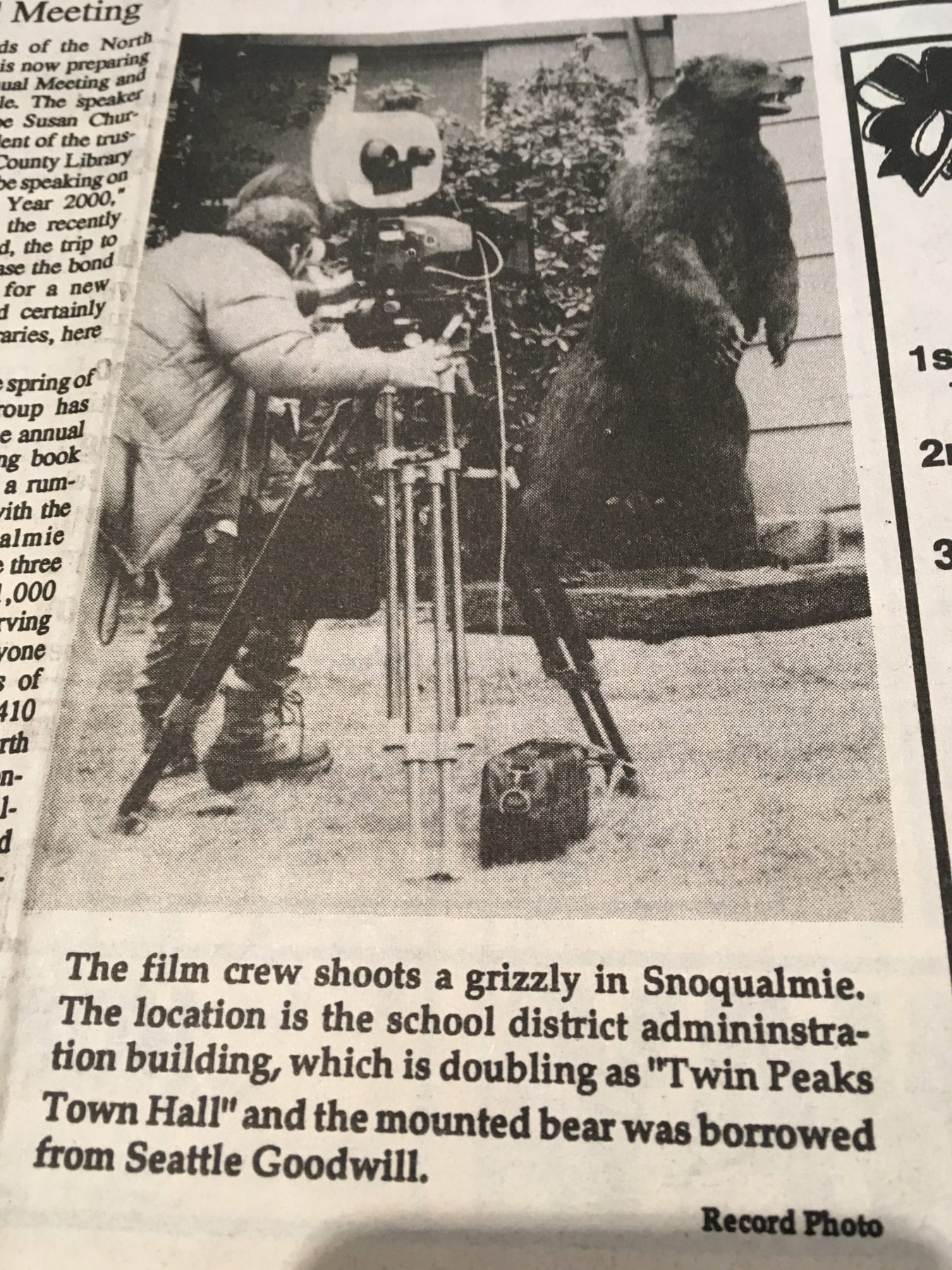

I grew up seeing that bear in the Seattle Goodwill dozens of times and never knew they borrowed it for the pilot. A piece of trivia I’d never heard – well done!