‘The Only Twin Peaks Access Guide Resource You’ll Ever Need’ is now available on Audio, written and read by John Bernardy, exclusively for our Patreon supporters. For just $3 a month you will have access to our full library of Audio content, plus three new uploads every week. To sign up visit our Patreon page: https://www.patreon.com/25YL

Welcome to Twin Peaks: An Access Guide to the Town has long been out of print, and therefore largely out of tangible reach for most Twin Peaks fans. 25YL and I are here to help! I will explore this book section by section while adding commentary, information gathered from podcast interviews, connections to the original TV series, and even some connections to Mark Frost’s The Secret History of Twin Peaks—which is fitting as Ken Scherer, COO of Lynch/Frost Productions, says this book “would have been Mark’s passion in a different place in time.”

Background

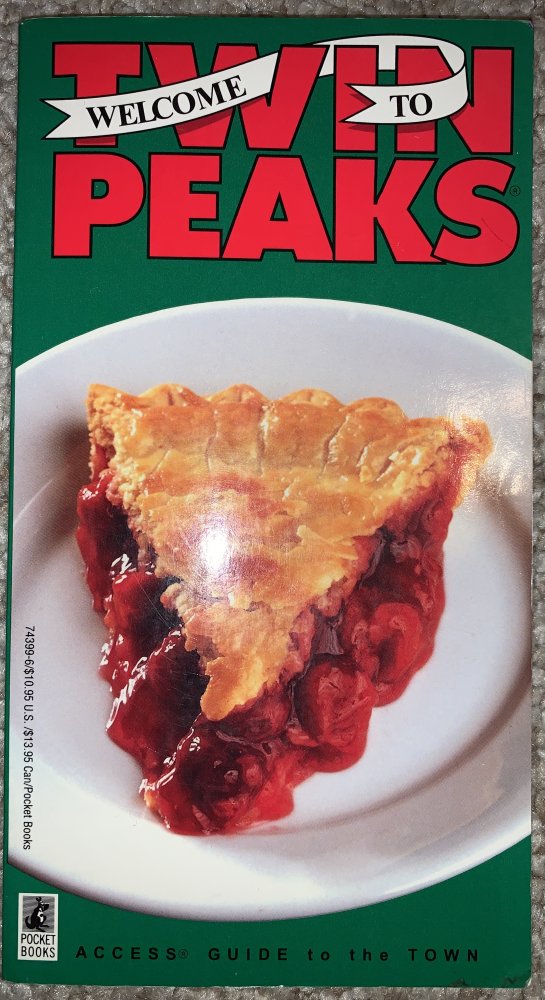

Access Guide was published in June of 1991, the same month the final episodes of Twin Peaks’ second season aired. It is meant to appear like an actual travel guide to the town of Twin Peaks. They even teamed up with Access Press, a publisher of genuine city travel guides, to do it as authentically as possible. The book covers every aspect of the town from local plant life to its founders to local festivals. It is also a joke on top of joke—some more effective than others—while containing details that can send fans dreaming of what could have been.

Frost, while being interviewed by John Thorne for Wrapped In Plastic #9,[1] had this to say:

I was originally approached with doing a novel. My idea was to do a Twin Peaks book a la James Michner: go back to the start with the geological formation of the peaks and the strange electromagnetic force that grew up between the mountains, and how it oddly affected all the people in the area, but I just got too busy and never got to it.

But that’s not the last we ever heard of these ideas, as we see early geological history of the region in the Access Guide. And that’s nowhere near the end of Frost’s repurposed ideas to be found here. Between ideas like these and the fact that Frost was fascinated at the time by Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, that explains the tone of this book.

Another explanation of the book’s tone comes from Ken Scherer during an interview with Deer Meadow Radio’s Mark Givens:

By the time we got to producing it, the steam had really gone out of the relationship with Mark and David, and with the show. And so I think the decision was made to have a little fun, try to be as respectful of the fanbase as we could be, but ultimately have a little fun with it and do the best we could.

Richard Saul Wurman, a publisher of Access Press, was approached to do this, and he thought it’d be a fun idea to do a takeoff on his own books and Twin Peaks. He worked with his team to do the art, layout and final wording in his offices. Mark Frost and David Lynch were involved. Twin Peaks writers were assigned topics to write about for use in the book. In Scherer’s words:

[We] kind of knew this was the end, and so in some ways we wanted to try to personalize it for ourselves, that we were here.

It was a fun way to kind of say goodbye to not only our jobs, it was also a way to memorialize some of the things that meant so much to us in the two year journey that we were there.

Wurman and his team assembled all these items and added their own touches, trying to “mirror the show and take it to an odder place,” as he told Twin Peaks Unwrapped’s Ben Durant and Bryon Kozaczka during an interview. They cannibalized anything they could and made this delightful book of marginalia and footnotes.

The Front Cover

When asked about the cover, Scherer laughed and said there were a large number of comments and notes on this. You’d think maybe it would look more together if Lynch was that focused on it, right? Not this time. Wurman says David Lynch wanted the art in the Access Guide to be “fuzzy, out of focus” and “unprofessional.” Mission accomplished!

When asked about the cover, Scherer laughed and said there were a large number of comments and notes on this. You’d think maybe it would look more together if Lynch was that focused on it, right? Not this time. Wurman says David Lynch wanted the art in the Access Guide to be “fuzzy, out of focus” and “unprofessional.” Mission accomplished!

From first glance, Lynch gave us a product that looks like it literally came from the earnest residents of Twin Peaks. And you know they tried really hard!

The Inside Front Cover

The inside front cover contains a simple map of the town. Wurman says maps are prominent in this book because he loves maps. The street names—aside from Lynch Road and Frost Avenue of course—are named after Wurman’s kids and friends.

Looking at the map, I notice a few things:

- The Sheriff Station is on the north side of Upper Twin Park, while the Gazebo is on the park’s lower side no more than two blocks away. This tells me if a deputy on night duty looked out the window, he could have easily seen Maddy Ferguson dressed as Laura Palmer, as well as witness Dr. Jacoby being attacked by a man in a ski mask.

- Lynch Road runs North and South, from Low Town—a location of a particularly harrowing drug deal gone wrong in The Secret Diary of Laura Palmer—up to a dead end at the railroad line. Its shape is not unlike an elongated question mark. It runs parallel to Highway 21, and both Horne’s Department Store and Calhoun Memorial Hospital are located on it.

- Frost Avenue runs East and West, from a dead-end in the corner of the residential district up to when it comes to a T-intersection at Highway 21. Sparkwood intersects Frost Avenue nearly in the middle of its length, and both the Sheriff Station and the Palmer house are located on it.

- Frost Avenue and Lynch Road do not intersect but work well keeping the aspects of the map tied together.

Page 1: A Message From The Mayor

This handwritten note from Mayor Milford—complete with scribbled-out words—begins the book. He suggests getting outside, enjoying the town, and asking random strangers “do you have that 10 dollars you owe me?” as a greeting. Aside from being more teasing in nature than his temperament on the show, the words could reasonably be attributed to Dwayne “Is this thing on?” Milford.

Milford dates his note April 1st, which is a pretty good clue that the people making this book think they’re writing a joke. My instinct says someone on the Access Press side wrote this, but no one’s owned up to the handwriting.

I do know that Scherer had just lost his father during the book’s production, so that explains the “In Memory of Herbert F. Scherer, Sr.” between the mayor’s note and the book’s indicia.

Page 2: Did You Know That Twin Peaks…

The next page is a silly list of trivia. None of it matters except to add a big “screw you” to ABC. Twin Peaks’ original network never liked the small-town population number for the show because they thought viewers would never relate to a show about a small town. They made Lynch and Frost add a decimal point to the population. Now Lynch/Frost Productions moved it back by saying “the 1990 census revealed our present population is 5,120.1 not 51,201.” This creates a weird joke about there being the possibility of 0.1 of a person (Maybe it’s the Arm).

The only other interesting detail I see here is that Twin Peaks is located exactly between an extremely cold Alaskan town and an extremely warm Arizona town. In-between states are all the rage in Twin Peaks, and this is one more instance, however much from happenstance.

Page 3: From the Will of Andrew Packard

This excerpt from Andrew Packard’s will declares that a sum to the town treasury be used to create a book “extolling and promulgating the many virtues and points of interest of our beloved community.” There we have the in-universe reason why this book exists, but it doesn’t exactly justify why the book was completed. Andrew Packard’s bio places him as presumed dead enough to put the funds in motion to create this book but also lists him as being alive. If this were a more serious book, I’d be curious why in-universe production continued on it even after Packard was revealed to be alive.

Regardless, these details place this book’s creation somewhere before when the finale had been filmed—Andrew perished for real in that episode’s bank explosion, though it was Catherine in the Episode 29 script.

As far as Andrew’s tone of voice, I believe Packard’s sense of civic pride is genuine, based on his giddy approval of Audrey exercising her rights of civil disobedience for the greater good of the town. He’d be the kind of guy who’d want his town to proudly sing its own praises.

Pages 4-5: Table of Contents

Next, we get a two-page spread of the book’s table of contents. Feel free to go to the sections directly through the links below, or go to the next page to follow the book in chronological order.

The Access Guide covers History, the Packard Sawmill, Flora, Fauna, Geology and Weather, Points of Interest, Events, Dining, Lodging, Sports, Fashion, Religious Worship, Transportation, Town Life, and Government.

Next: Twin Peaks History & Packard Saw Mill

HISTORY

Pages 6-9: Twin Peaks: A Brief History

The four pages devoted to early history give us the arrival of James and Unguin Packard, then Rudolph and Pixie Martell, and Orville and Brulitha Horne. We learn that Twin Peaks was a small collection of refugees, trappers, and thieves. In 1888, Thor’s Trading Post was the only business in town but that all changed in two years when the Packards arrived.

Page 6 is devoted to the Packards. James Packard brings his name to town along with his plans for a mill, but his wife Unguin is the one we need to talk about:

- She was 12 when she arrived, and while that may be meant as a creepy child bride “joke,” that makes her the same age as Laura Palmer at the beginning of Secret Diary.

- Dabbling in the mystic arts is something Madame Blavatsky was also doing while popularizing Theosophy, a known ideology in later pages of the Access Guide.

- Her “true home,” the land of Bloon, is beyond the solar system. In The Secret History of Twin Peaks, it’s inferred that the Giant may be from Sirius, also well beyond the solar system. Did the writers just imply she’s from the Lodge? Probably not, but they’re sure asserting that she’s had contact with the Lodges.

Page 7 lays out the misfortunes of Pete Martell’s ancestors—who arrive after the Packards—-to easily show Pete doesn’t fall far from the tree. This entry doesn’t mean much at the time, but it does mean something when The Secret History of Twin Peaks directly reverses things when the Martells arrive first before the Packards come to town.

There’s a quote in the margin “from” Mark Twain that begins a fun series of nods to famous writers writing about Twin Peaks in their own style found in the Access Guide. You’ll see this happen with a number of figures.

There’s a quote in the margin “from” Mark Twain that begins a fun series of nods to famous writers writing about Twin Peaks in their own style found in the Access Guide. You’ll see this happen with a number of figures.

Page 8—about the Hornes’ arrival—contains three items of note:

- Mentioned poet Hugo Boot is a fake identity with a fake book from a fake publisher. We get an even mix of fake books and authors and real historical figure references.

- The first Truman in town, Crosby, is a problem-solving inventor, rather than always being a lawman as reported in Secret History.

- The Hornes burned down their competitor’s entire business in order to score a win, just as in present-day with the Packard Mill. This means the Hornes are exhibiting yet one more cycle occurring within Twin Peaks.

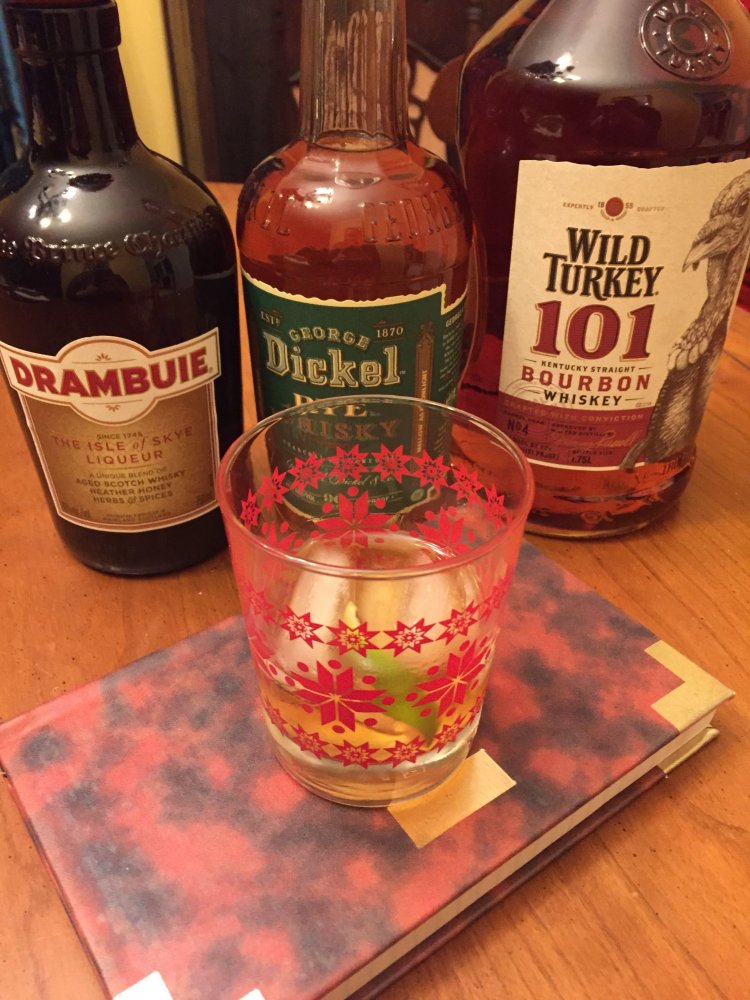

Also, the margin contains the history behind and the recipe for a drink named the Little Scottie. This drink was created by Twin Peaks’ first mayor in what would become the Roadhouse. Is the drink any good? We have this review of the Little Scottie from Rachel Stewart:

A Little Scottie Goes a Long Way (or TL;DR: THIS IS A STRONG EFFIN’ DRINK)

There are few things I love more than bourbon, rye, and Twin Peaks. So when I found out about Little Scotties in the Access Guide, I knew I had to try one. So I dusted off my minimal bartending skills and mixed one up, per the recipe:

Two parts bourbon, one part rye, a dash of Drambuie and a twist of lime.

All I can say is yowza! I’m all for whiskey heavy drinks, but this one is potent. The Drambuie adds a nice sweet note you’d get if you were ordering an Old Fashioned or Manhattan. If you’re a fan of the Rusty Nail, I’d give this one a try. The Access Guide recommends pairing the tipple with cheese and crackers, but I prefer it as a digestif or nightcap. Just don’t make it a double or you’ll end up feeling like you’re in the Pink Room from Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me.

Page 9 takes the Mill and Hornes up to the present-day status quo of the Access Guide. There is also a quick note in the margin about Oscar Wilde, and a margin bio for Josie Packard.

I thought the most interesting part of this page would be how the Access Guide repurposed text from the back of the Star Pics trading card set for Josie’s margin bio. Boy was I ever surprised that the text was completely new. Looks like those trading cards have more to them than I thought.

The inclusion of Josie’s margin bio here—and no mention of her death in Episode 23 while actually mentioning Andrew Packard’s reappearance—is another implication that the timelines of the books are dated from when they were published in the real world rather than the show’s year of 1989, while simultaneously syncing up with the TV show’s current plotlines and status quo.

And, was it really a coincidence that Josie’s bio shared a margin with an anecdote about Oscar Wilde? We knew Josie was already dead upon Access Guide’s publication, and Wilde was already dead for a few years when the book says he visited the town…

Pages 10-11: The Old Opera House

This two-page section uses their top halves to show us a picture from the audience seats to the view of the empty stage, and a picture from the stage to a view of empty audience seats.

Unlike the fake poet on page 8, Sara Bernhardt, Charlie Chaplin, and the Guess Who are all completely real public figures. No embargo of real-world references here. What were they doing in Twin Peaks? Performing at the Opera House.

The building was built in 1882, burned down, rebuilt in 1915, became a place that put on music concerts, and shows movies regularly.

Ben Horne’s margin bio is listed on page 10, as he’s credited as reviving the Opera House. I find his bio interesting due to his listed belief in the “restorative power of song.” Not only does that match with the prominence of the Roadhouse musicians in Season 3—or Audrey dancing in the diner because it’s “too dreamy”—it also links to Ben’s ability to hear the humming in the Great Northern. It’s nice to see such a thematic foundational detail dropped into this “frivolous” book.

Besides the hum he and Beverly repeatedly try to locate in Season 3, he also spins around in Episode 27 to witness an unknown thing when he hears a creepy humming sound. At the time, I believe the writers meant it to be Josie’s spirit trapped in the hotel’s wood, but based on Ben’s actions in Season 3, it seems like he’s tuned enough to sound that he can recognize the barrier between states of reality (but whether he can recognize the barrier as a barrier is another thing). I suspect Peyton and Engels were thinking about this when one of them wrote this page.

In the margin of page 11 is an ode to the “versatile huckleberry.” Plain as the description is, I bet this page’s ode has to be a nod to Major Briggs’ professed love for the Double R’s huckleberry pie that he expresses in the early episodes of Season 2.

Pages 12-14: First Inhabitants

The next two and a half pages are devoted to the first settlers of the area. We get the beginning of the running joke where the only people who stay in the area don’t tire “of the thick, gloomy forests and the disturbing sounds of the owls.”

Unfortunately, we also get humor based around tropes such as “Indians as savages” which really doesn’t fly anymore. Not even with a final sentence on page 14 about their culture only now beginning to be understood by “foreign cultures that engulfed but never embraced it.” Not cool, 1991.

I suspect the actual serious details found in pages 12-16 came from a project about Crazy Horse that Ken Scherer says he was working on with Mark Frost at the time.

But then there’s that page 14 margin note about the Frog Clan—and an included picture of a totem pole style carving of a frog with wings—seems a lot more like a potential origin for Lynch’s Part 8 frogbug. Is there a connection? Maybe, but the only things Lynch verifiably added to this book was the cover and the advertisement for Tim & Tom’s Taxi-Dermy.

Pages 14-16: First Explorers

On pages 14 and 15—between ethnic jokes about anyone crazy enough to settle in the region—we get characters’ initial reason for settling: a superficial fashion trend like beaver hats. Sounds about right for this book.

Luckily it gets substantive again on page 16, which begins with an altered map of the Lewis and Clark route that drastically diverts itself enough to cross paths with Twin Peaks. Lewis and Clark have always been a part of the Twin Peaks backstory according to Mark Frost. This page is your proof.

Less than an inch away, we see Dominick Renault’s story also paralleling Secret History. Renault’s final words were found in dairy pages, exactly how similarly shady Denver Bob’s story was revealed. Renault survived this book’s jokes about being a stand-up comic only to succumb to the woods.

Renault’s story follows suit with other character moments we’ve already read in Access Guide:

- Just as Unguin Packard felt like her home wasn’t with the people of Twin Peaks, we see Dominick Renault becoming part of the forest and its wildlife, which we can infer means he too had a Lodge-related experience.

- As Ben Horne believed in the importance of song and sound, Renault’s “anguished voice” becomes part of the resonance of the owls. The power of sound is associated with the owls here, again connecting to a property of the Lodges.

The power and gloom of the woods are always just within reach, even within the absurd and comic tones of this book.

Page 17: County Museum

The single page devoted to the County Museum is next. The museum has a permanent collection of artifacts, yet it’s only open from May through September—that’s five months. Inefficiency!

It’s a joke, but then there’s that margin note connecting the Hornes’ pictured totem pole to the pre-arson Thor’s Trading Post. That’s proof that a Horne will always burn down the building of their staunchest business rival, but the book drops it in like the punchline of a joke. Just don’t forget it’s also evidence of another repeating cycle found in official Twin Peaks material.

THE PACKARD MILL

Pages 18-19: The Packard Mill

This section begins with a single picture spread over pages 18 and 19. It shows us the Packard Mill in action, with a log propelling on a track towards the camera.

Pages 20-21: The Packard Mill Then

These two pages have a little bit of everything:

- Catherine Martell’s margin bio.

- A picture of lumberjacks using springboards as they pose in a giant tree.

- An illustration of a crosscut saw detail.

- A picture of a skyhook cable car in action.

- The birth of the Mill from two acres off Black Lake Falls to the expansion and how it handled the war years. Lots of factually accurate machines mentioned.

You can tell the authors were having fun with Catherine’s margin bio on page 20, listing her preference of “the Horne” and putting the quote marks around Elvis Presley to turn him into a euphemism. I suspect the writers were also fans of Piper Laurie’s early films and felt inspired.

Besides that, is trading cough drops for land supposed to be a good joke? That’s how James Packard supposedly resolved an altercation with the local Kwakiutl Indians. It makes me cringe to see what was once acceptable humor.

Pages 22-25: The Packard Mill Now

Pages 22 and 23 focus mostly on the Mill modernizing up through the 1991 publication of this Access Guide.

Among the requisite jokes about a company bragging about the last injury-free year nineteen years earlier—and that safety comes just after profit and management perks—we get a reference to Theosophy.

I mentioned earlier how Unguin Packard’s portrayed in a similar light to Madame Blavatsky, and here we have another reference to Theosophy with Bill Gross—manager of holding and drying—declaring himself a Theosophist. As Mark Frost bedded the show’s mythology in Theosophist beliefs, it only stands to reason that the characters he creates would be tuned to that philosophy somewhat regularly.

There’s a story in the page 23 margin about how early superstar actress Sarah Bernhardt got her wooden leg made for her while in Twin Peaks. This would’ve been funnier to me if I’d known she ever had a wooden leg, but that’s my fault, not the book’s.

Next, pages 24 and 25 are filled with illustrations that demonstrate the kind of cutting each blade and saw use as they turn trees into lumber. We also get a breakdown of the Packard stamp that is applied to each piece of wood. This is technical stuff with little joking. They saved all the jokes for whittling.

Pages 26-27: The Joys of Whittling

This two-page section is a goofy how-to list of how to best enjoy the fad of whittling, along with pictures of hands missing fingers, a “big ugly wood bear” carving, Cooper’s whistle, an illustration of a knife, and Dale Cooper’s bio.

In his interview with Deer Meadow Radio’s Mark Givens, Harley Peyton declared that he wrote the whittling section. Richard Saul Wurman recounted in his Twin Peaks Unwrapped interview how he remembers creating the visual jokes in the whittling section. The whittling page is often the first thing I remember about the book, too; it’s a fun page for sure. A memorable time for all!

I love that the prop for Cooper’s whistle is included here. Cooper’s page 27 margin bio also yields some interesting information:

- Dale is linked with the Theosophist Society.

- An unnamed tragic incident has happened in Dale’s recent past. It implies the death of Caroline Earle, but that was closer to four years earlier according to The Autobiography of Dale Cooper: My Life, My Tapes. In some ways that’s recent but it’s not the year before like The Final Dossier and this book seems to think.

- The phrase “might well have been a magician or mystic” has the show’s writers connecting Dale to the only identity mentioned in the “Fire Walk With Me” poem. It’s never been more explicitly connected than right here that Dale is like the enigmatic magician that longs to see.

Page 28: The Wood Mistress

We get a margin illustration of the kinds of cutting that happens to logs to turn them into two by fours and four by eights, among other things, but the main draw is learning about wood mistress Helga Brogger, who selects what wood is turned into what kind of product. She knows because she listens to the wood and knows what they want to be.

Per this page, Brogger is likened to be the worldly-leaning counterpart to Margaret Lanterman. They both have conversations with the wood, but it seems Helga’s all small talk and flirting rather than receiving ethereal portents.

In a way, it seems the writers place Helga between the Log Lady and the Palmer women. After all, she says “it runs in the family; women of vision, the backbone of Twin Peaks.” Who else could be implied here besides Margaret, Sarah, Maddy, and Laura?

Next: Flora and Fauna

FLORA

Pages 29-36: Twin Peaks Flora

As the flora section begins, we get the margin bio of “sometimes naturalist” Dr. Jacoby on page 29. I assume they’re implying he’s a pot smoker, but they also share the lovely detail that surfaced on Jacoby’s trading card and later in Secret History: that his glasses’ colored lenses “balance the right and left sides of his brain.” I love that detail in so many different ways, and am so happy that’s always been part of his character.

I suspect the Flora and Fauna sections were mostly written by the Access Press writers, as we have some proof in reference to Sparkwood and Blue mountains as well as Lower Town, rather than White Tail, Blue Pine, and Low Town. All told though, they keep on the theme well enough, especially with the mention of people disappearing in the woods, not unlike the Major in Season 2 and the Log Lady in Secret History.

Page 30 is all about lilies, and its margin has detail about a Snoqualmie legend of the tribesman and the mountain lion that help each other and turn to lilies when they die. It makes me think of the “intercourse between worlds” the Arm spoke of in Fire Walk With Me. Beyond that, it’s fairly straightforward stuff.

For being a tongue-in-cheek version of plant journals, Access Guide makes sure to include a Twin Peaks touch on every page. Such as Margaret’s log on page 31.

Page 32 includes text about Douglas firs, and an illustration charting sizes of the various local trees which is right below a size comparison of the great horned owl and pygmy owl.

Page 33 has text on local trees, along with an illustration of leaves and a margin bio for the Log Lady. Margaret crediting Glastonberry Grove among her Bests is interesting. Did the writers know at the time about her jar of scorched engine oil?

Earlier, I noted how the only people who stay in the area don’t tire “of the thick, gloomy forests and the disturbing sounds of the owls,” and that the only reason they settled was beaver pelts. Here, we see it’s a theme: the beavers’ favorite food is the Quaking Aspen, known here as weak wood. Even the beavers who stayed in the area choose a food that doesn’t put up much of a fight.

Page 34 has text about different local moss, and illustrations of the moss. The margin describes a plant named Devil’s Club.

I’m not a fan of Gaston Leroux being playfully described as a pedophile for a joke just to go along with some comments about moss, but his diary being found near both Owl Cave and his bones is a story I want to hear. I’m again reminded of the Denver Bob portion of Secret History.

Next, page 35 gives us text filled with absurd humor about poison ivy, along with a margin bio for Deputy Hawk. The poison ivy goofiness is just that, making ridiculous claims about how to deal with it. I wonder if the writers leaned so far into it to balance out Hawk’s classy margin bio. I’m really glad only the Timber Games were mentioned in Hawk’s Bests list, rather than his stereotypical Timber Games specialty, Bury The Hatchet (Thanks again, 1991).

Page 36, the last page of the main Flora section, contains text about tanning hides, with margin illustration for types of spud tools.

Page 37: The Twin Peaks Flower: A Pine Cone

On this single page, we get text about the official Twin Peaks flower: a pine cone. A giant illustration of one takes up the bottom two-thirds of the page with a gorgeous etching of a pine cone. But yeah: a pine cone is not a flower. And Twin Peaks somehow adopts it as one anyway. I get it—absurd humor!

I think Andrew Packard would have a little less civic pride as a result of this being a real town fact, so I’m blaming this detail on the Access Press directive to “mirror the show and take it to an odder place.” But why the folks on the Twin Peaks side signed off on this too (it’s not that funny), I’ll never know.

FAUNA

Pages 38-40: Fauna

Page 38 includes text about a squirrel, skunk, and the pine weasel, with illustrations of them, along with a button for the Save Ghostwood movement in the margin. Is it wrong that I love all the pine weasel stuff?

It’s certainly fun to see the ferret by another name get its due, but get too focused on it and you’ll miss the nod to Rocky the flying squirrel. You’d think the writers would’ve thrown in a nod to Bullwinkle somewhere, but then there’s that classy White Moose legend in a few pages.

Page 39 gives us text about beaver, raccoon, mule deer, and the beginning of the taxidermy section, with margin illustrations of bear tracks and claws. On page 40 we get rather graphic illustrated steps for taxidermy, as well as the beginning of the white moose legend.

Pages 40-41: The White Moose

The sad legend of the white moose concludes on page 41. A negative image of a moose is at the bottom of the page. Moose track illustrations are in the margin, and an incongruous ad for the Bell Club Lodge is placed in the corner.

Legend tells us the white moose appears on moonlit nights as a ghost. It’s mentioned in many characters’ written accounts but only Dominick Renault has claimed to see it, which makes sense assuming his dark path. Legend has it the moose was the lone survivor of 50 moose that were exterminated by the several dozen trappers that trapped them. Now, “drained of his brothers’ and sisters’ blood, the White Moose appears to those in trouble because it understands the agony of sorrow and despair.”

There’s a lot in the legend of the White Moose. As Lodge denizens seem to take different shapes depending on who’s observing them—say the Land of Bloon to Unguin Packard and owls to Dominick Renault—I wouldn’t be shocked if that meant the White Moose and White Horse weren’t one and the same.

I love that the “melancholy and forgiving” White Moose “appears to those in trouble because it understands the agony of sorrow and despair.” Was the horse—at least during the days of Twin Peaks’ original production—less a drug metaphor and more a witness to validate and understand someone’s pain?

I now want to go through every scene the horse is in and decide whether it could be a presence of compassion much like Carl Rodd was for the unnamed mother in Season 3.

Page 42: Owls Club

This page begins with a paragraph about the Owls Club, which is described very much like an Elks Club, except here the elks are mounted on the wall.

I want the Owls Club to mean something, but I suspect this was another of those moments where Wurman and his Access Press team tried to “mirror the show and take it to an odder place.” Below the text of this under-explained group is an illustration of a properly pinned and mounted elk head.

Page 43: Antlers

This page literally describes the process of growing antlers, dropping antlers, and needing to repair your antlers. It reminds me of the head that “fell off” in the bank scene of the Pilot. Otherwise, I only note that the illustration of different antler types was well done.

Page 44: Birds

Page 44’s descriptions of the Yellow-Rumped Warbler, Common Crow, and Turkey Vulture (the last is pictured largely on the page’s bottom half) were almost written like dating profiles, which I found charming.

But it was the details on the Great Horned Owl’s harmonizing that are a winner. In reference to “in concert, they often harmonize in perfect thirds, though around Twin Peaks diminished sevenths are heard.” Em, host of the Sparkwood & 21 Podcast, had this to share:

Schoenberg had written about the diminished 7th: whenever one wanted to express pain, excitement, anger, or some other strong feeling, there we find—and almost exclusively—the diminished 7th chord.

She and her co-host Steve had no problem believing that owls from Twin Peaks could and would convey different emotions than normal owls.

Page 45: Creation of the Owl

We next get a fable in one page about a daughter being convinced by her mother to fly away as an owl, and then the mother takes her daughter’s skin to eat their food and sleep with her son-in-law. The daughter tells him what’s happening, he ends up killing the mother, and he also has to leave his skin as it was the only way to be with his wife again.

Based on this tale of the owl’s creation, I can’t see it any other way than being yet another Lodgespace interaction under a different name like the Land of Bloon.

- A mother negatively coerces her daughter to become part of the woods.

- The mother is killed for her hubris.

- The daughter’s rescuer has to enter the Lodge for any hope of being with her. And they can’t get out unscathed.

Sounds like we heard a variation of the first point with Laura Palmer’s story, the second with Leland’s story after he kills Maddy, and the last point in Episode 29 with Cooper and Annie. Can you see it, too?

Even the scientifically-grounded margin details about the bird seem to make connections between the Great Horned Owl and Lodge denizens:

- Seeing in total darkness fits well—especially when considering one Lodge over the other.

- Then there’s triangulating sound collected on the feathery disks—one could call them circles—in front of their eyes. It’s almost like they see sound. And we’ve seen already that the Access Guide values the importance of sound frequencies.

Pages 46-47: Owlwise By Firelight

The background to this two-page spread is this final moment from the end of Episode 16:

The overlayed words are poetic, describing the outdoors at night by firelight, followed by the appearance of an owl, then its mate, and their sounds of a perfect thirds chord. The writer is certain the owls know what the people do not, and the passage ends with a thought that the owl’s wings will one day engulf them and tell them things they want to know as well as the things they don’t.

Riding on the coattails of page 45’s legend, this section could be the thesis statement of Twin Peaks Season 2. Possibly even Twin Peaks as a whole.

Finding a mate allows for harmonizing in perfect thirds. That makes love the key to creating a harmonically balanced chord. A diminished 7th comes from dread, an aspect of fear. Love vs. Fear is the major theme of Season 2, most notably in how those two emotions are the keys to open the door between worlds.

“Not dread but a connection with our past is what we feel” implies so much that I can’t quite articulate. But I can say what this literally says. Connections and the understanding of how you got to your present are positive forces, the opposite of dread. Therefore they are adjacent to love.

Pages 48-53: Pete Martell: Landing That Big One

Page 48 is devoted entirely to a black and white version of a poster titled “Trout, Salmon, and Char of North America.” 36 fish in three rows. And the page tells us we can buy the poster on page 112.

You absolutely can not order that poster on page 112 like the caption says—though you can on page 111—but you can guarantee one these local fish made their way into at least one percolator.

Over the next four pages, we get Pete Martell—not Ben Horne, who also lays claim on catching that 45-inch sockeye on display at the Great Northern—writing us a classic yarn of a fish story.

Make sure to note a few things in Pete’s page 49 margin bio:

- He’s certainly a chess man, preferring chess over the checkers he preferred in The Secret History of Twin Peaks.

- He counts the Passion Play among his bests. Keep track of that for later.

- He mentions the Green Butt Skunk, which is Harry Truman’s going away present to Dale in Episode 17. This tells me Pete taught Harry everything he knows about fishing.

A large illustration of sockeye salmon spreads across the top of pages 50 and 51. Margin notes contain background info on salmon, and the main text is part of Pete’s fishing advice. Then Pete’s story concludes on the next page with a list of eccentric items in Pete’s tackle box. An illustration of chinook salmon spreads across the bottom half of pages 52 and 53.

Pete includes his list of tackle box contents following the end of his story. I enjoy that he was either too scatterbrained or too excited to fill in spots 27 — 30. Did he lose them when he spilled its contents out and can’t remember what they were?

The section concludes with a pictorial list of lures on page 53. Two particularly Twin Peaks-esque items stand out:

- The previously mentioned green butt skunk is the second row from the top, all the way on the left.

- On the top right corner is an Annie. Is this a subtle way to make a joke about how the writers intended Annie Blackburn to be nothing more than a lure for Dale Cooper to enter the Black Lodge at the end of the season? If this was an easter egg, it’s a slick way to put it out there.

Next: Geology and Weather, Points of Interest

GEOLOGY AND WEATHER

Pages 54-55: Twin Peaks: In The Beginning

This next section is the original idea that became the Access Guide. It is 100% Mark Frost’s ideas and probably began with his words as well. I remind you now of his quote from Wrapped In Plastic Magazine #9:[1]

My idea was to […] go back to the start with the geological formation of the peaks and the strange electromagnetic force that grew up between the mountains, and how it oddly affected all the people in the area

On page 54 we get a short explanation of the creation of those mountains 100 million years ago, and on page 55 is the post-ice age creation of the waterfall—the source of the electromagnetic force—between them.

This geologic history of the Twin Peaks area covers the creation of the mountains. It also places the Gas Farm on exactly what used to be the continental coastline. Big Ed’s margin bio is on page 54. The other page explains the creation of Pearl Lakes and White Tail Falls, along with a local advertisement, images of fossils, and an illustration of ice age effects.

Obviously these pages are huge for lore, but how’d Big Ed and his Gas Farm get placed there? If I had to guess, it’s a perfect confluence of “how are we going to connect this stuff to modern-day Twin Peaks” and “where are we going to put Big Ed’s bio?”

The effect turns out to be an endearing way to frame the past, but it ends up being more thematically connected than that. Anyone who watched that Season 3 credits sequence where Ed eats soup at the Gas Farm, you can make a case for it being another of those in-between places like the Great Northern or the Roadhouse. Being on the shoreline between the old coastline and the new coastline fits well with that portrayal, whether intentional or from happenstance.

Pages 56-57: Weather Watch

Page 56 tells us the typical climate of Twin Peaks ranges from 30 degrees to 66 degrees Fahrenheit. We’re also told about the extreme snowfall of the 1889 blizzard. In the margin is a graph of precipitation records, visually measured against the height of Big Ed.

“We get lots of frost” has to be a pun about Mark Frost, doesn’t it? And seeing Big Ed again on the graph to provide a frame of reference is smile-to-yourself funny.

There seems to be a moral to the way humanity vs. nature is portrayed here, explained best between “the mountains don’t care; we do” and James Packard’s pleading “we are industrious, why are we not blessed?”

Nature does what it does—probably cyclically—and people can’t control it. Especially not the settlers who are comfortable in the region’s melancholy and regularly find themselves suffering misfortune.

Pages 58-61: Tim and Tom’s Taxi-Dermy

Let’s shift gears and welcome back David Lynch, who photographed the following four-page “ad” for Tim and Tom’s Taxi-Dermy.

The ad stars Twin Peaks producer—and future producer of Deadwood and True Blood—Gregg Fienberg as Tom, and David Lander—Twin Peaks’ Mr. Pinkle and Laverne & Shirley’s Squiggy—as Tim.

I would’ve loved watching those three guys running around for the hour it probably took to stage this photoshoot. I imagine this ad was born when Lynch had a twinkle in his eye, Fienberg and Lander were the first people he came across on a set, and he said “Fellas! Meet me at the parking lot in ten minutes!” before he raided the costume department.

I can’t prove it officially, but I think Lynch wrote all the ad copy too. Read it in a Lynch impression voice and its humor will make so much more sense.

It begins with a two-page spread of the car in a profile, windows rolled down, and both brothers leaning out in ridiculous outfits presenting us with thumbs-up signs. Above the picture is this text:

We’ll drive anyone anywhere*

We’ll stuff anything, even a bear**

below the picture in a smaller font is this text:

* (Within Twin Peaks City Limits)

** (Has to be dead.)

Next, we get a spread of four panels over two pages. Along with a picture of the front wheel and fender in the first-panel comes this caption:

Through the magic of telepathy, blind Tom pictures vividly everything his brother says. Born in Twin Peaks, never having left for anything, the brothers are inseparable. The only time they’re not working is when they’re sleeping—and even then they’re sawing logs.

The next panel has Tom looking out the car window in sunglasses with his winter hood pulled up, along with this caption:

Tom says: “Don’t be nervous, just close your eyes like me.”

Next panel has a long-distance shot of the original picture, with this caption:

Come ride and stuff with us.

And lastly is a panel looking into the rear car window at Tim, who is sitting straight, looking forward, and wearing a mask over his eyes. The caption says:

Tim says: “Tom’s blind…come ride in back with me I’ll drive.”

Against all odds, I really enjoy how thematically connected this goofy ad is. The telepathic connection between the brothers, even when they’re “sawing logs” sure sounds familiar if you’re willing to look at how Dale is connected to dreams.

Also, it’s all about letting go of fear, closing your eyes, and letting intuition take you where you want to go. Again, Cooper worked best when he trusted the flow of things, but it also seems like a metaphor for how Lynch talks about meditation.

A silly ad? Yes. A list of Lynchian ideals? Also yes.

POINTS OF INTEREST

Pages 62-63: White Tail Falls

Spread across the top two-thirds of pages 62 and 63 is a large photo of the White Tail Falls in action, taken from the Twin Peaks credits sequence. Below the image is text explaining how strong it is, making the connection explicit between the Falls and its electrical energy. This puts a bow on the earlier-included Mark Frost quote.

Yet there’s more to be said from the margin note about “so magical are the powers of White Tail Falls that anyone who has ever fallen in love within the sound of their plunging water remains in love forever.”

The sentiment matches well with this book’s earlier references to the power of sound. But how else are the powers of the Falls magical?

- The hum Beverly and Ben tracked not only seemed to tie them together in love rather than fear, but it also originated at the base of the Falls.

- James Hurley followed that same hum to a door in the basement at the base of the falls in Part 14. This is the same door where Cooper went with Gordon in the Final Dossier version of Part 17’s post-climax events.

- Long before this in Secret History, Merriwhether Lewis took a pouch—containing an Owl Ring—to the base of the Falls to get some form of otherworldly help.

Whichever way you look at it, the Falls are a major source of otherworldly power in Twin Peaks.

Pages 64-65: Owl Cave

I wanted this two-page section on Owl Cave to be so much more than what we got here. Instead of supernatural connections, there’s a list of groups that used it for social gatherings or hiding out. I get that this book is supposed to be a tourism guide; I can’t get every bit of deep dive that I want. I’ll just have to make do with the fact the Access Guide mentions messages had been left in the cave “from beyond,” and that the actual Owl Cave map drawing from the show was included at all back in pre-internet times when something like that wasn’t easy to come by.

The page 65 margin note on the extremely secretive society known as Circulars seems to be a way to include Dugpas under a new name, though here they’re presented strangely. Their only claim to fame noted here is that they tried to rename the cave “Elk Cave” during the Truman presidency years.

Page 66: The Grange

The Grange is the only undamaged building from the Smallish Earthquake of 1905, and it housed the sheriff’s office, the county seat, chamber of commerce, voting hall, patrons of husbandry, and Pierre’s Smoke and News Cafe. The margin feature showed this town center was even visited by President Harry S. Truman, thus inspiring the town sheriff’s name years later.

What happened to the important building? It was burned down during a snowstorm in 1953. And when arson was revealed to be the cause, it pit neighbor against neighbor.

This section is possibly a statement on arson being a cyclical event in Twin Peaks or a clue that the Hornes are at it again somehow on their way to becoming the central importance of the town. Either way, it’s the mark of how prosperity ends and fear asserts itself.

Page 67: The Train Graveyard

The other way to show the end of a period of prosperity is the next page’s section on the Train Graveyard. This section speaks to the death of the Great Railroad Era, characterizing the trains as if they were noble majestic beasts. The section ends up equating the end of their era to be the same level of tragedy as the death of Laura Palmer. After all, they practically come out and say it:

Now, together in their graveyard, they witness things which, could they tell us, would chill our bones and rob our nights of sleep.

I’d like to think the in-universe writer of that entry was thinking of Laura when they wrote that, and it was one of the only ways in the Access Guide to talk about where she was killed. It ends up feeling like one more capper on a period of prosperity before darkness.

In the margin, we get illustrations of various engine smokestacks.

Next: Events, Dining, and Lodging

EVENTS

Page 68: Twin Peaks Passion Play

Page 68 is probably the most important page in the whole Access Guide.

In his Deer Meadow Radio interview, Harley Peyton had this to say about seeding future plot points into the Access Guide:

Sometimes we were just doing our jobs and other people would find mystery in it. […] then the theories come back to us, we start implementing them into the show.

That said, I am confident that there are elements ripe for use in what could have been the Twin Peaks Season 3 that would’ve aired during the ‘91-‘92 TV season.

This page describes 12 ancient Douglas firs that form a circle and “appear strong enough to support the sky,” found in Glastonberry Grove. The first paragraph suggests how the trees have stories to tell if only they could. Despite a conspicuous lack of the word “sycamore,” this is where the Passion Play occurs.

Here are the particulars:

- It is an evolving—rather than set—ritual.

- It occurs in April, though a specific day and time are never announced.

- The participants gather around the 12 Great Firs.

- Six cassocked figures emerge, bearing sword, chrysanthemum, crucifix, and chalice.

- The mysterious guardian of the gate appears from an untraceable location.

- Event sponsorship is unknown, but it’s rumored to be the “ultra-secret” Bookhouse Boys.

- The event lasts all night.

- At dawn, sunlight obliterates darkness as Good vanquishes Evil.

- The next Passion Play will occur sometime in April ‘92.

In the margin, we get a creepy image of a bearded man with whites for eyes, which to me says doppelganger. There’s also an image of the classic Bookhouse Boys patch.

What’s to make of all this?

- If it’s an evolving ritual, the TV writers could make it into any kind of scenario they wanted when the time comes.

- April of ‘92 would coincide with when Season 3’s concluding episodes would be airing on our televisions in the real world. (More evidence that books sync up with actual time rather than the show’s ‘89 continuity.)

- The sword, etc. match up well with Arthurian grail quests, which would also go well with the sword Harry receives from a Lodgespace figure in the Episode 29 script, as well as Arthurian ties to Theosophy.

- The guardian of the gate sounds a lot like this guy, who was also at the scene of the Briggs abduction in Episode 17:

What else does this page suggest? Thematically, light and darkness have been on the show’s mind even longer than the duality of Love vs. Fear. I bring up Margaret’s lesson of “push through the darkness and grow your light” that surfaces blatantly in The Final Dossier.

As interesting a detail is how the Bookhouse Boys are “ultra-secret.” I like the idea that they operate in town loud enough to be noticed, but quiet enough that the locals making the town’s Access Guide think the battle against darkness in the woods is less of a cyclical battle and more akin to some live-action Portlandia skit.

Pages 69-71: Packard Timber Games

The next three pages cover the events that take place a half-mile north of Sparkwood and 21 every August. The Packard Timber Games were founded in 1910 by James Packard, and the seven events are Caber Toss, Spinoff, High Climb, Bury the Hatchet (which Hawk is stereotypically the master of), Stone Throw, and Trunk Chop.

Each event is described in a short paragraph, sometimes logistically and sometimes with a silly anecdote that happened in past events. There are also large illustrations of men competing in some of the events. In the margins, we get the process of how to hang an ax.

Pages 72-76: What To Do and When To Do It

A four-and-a-half page calendar of community activities and events comes next. It oddly starts in December and skips over June and November.

- December has the Candlelighting and Christmas Tree Ceremony, along with the preschoolers’ Magi Pageant—complete with live camels and sheep. It goes all day. Carolers sing in turn-of-century costumes and Miss Twin Peaks turns on all the lights at the end.

- January has a Scandanavian tradition called Winterskol, which involves a lot of drinking and an ice castle competition.

- February has an annual Chess Tournament. Pete presides over it. Past noteworthy challengers include Vladamir Nabokov.

- March has my favorite of the events: the Caribou Festival, which takes place instead of St. Patrick’s Day. Competitors dress head to toe in fur & try to replicate the most accurate imitation of the caribou mating call. Why do I think this is so funny? Because I imagine Josie—the character most often seen in fur coats—choosing to forego her dignity and compete in this thing.

- April shows the Yellow Lupine Festival has a 10K run and is also what the Miss Twin Peaks competition is part of.

- May has the Gardens & Homes Tour, where residents open their homes to the public after furious cleaning. It’s put on by a secret women’s philanthropic society known as the PEO. It’s never mentioned again but could it be the equivalent to Bookhouse Boys? We’ll never know.

- July has the Fourth of July Celebration. There are lots of events like inner tube races, and we get our first mention of the Wagon Wheel Bakery. Angelo Wong—restaurant owner to be mentioned later—is the guy behind the extravagant fireworks display. It really gives a lived-in Whole Damn Town feeling when names like Wong, Tim & Tom’s, and even Unguin Packard keep popping up in different contexts.

- August has the Twin Peaks Timber Players putting on Theater Between The Bleachers at the high school.

- September is where the Packard Timber Games are listed even though its own section placed it in August; sometimes callbacks work better than others. But I do like how the event’s prize is called the Wooden Thing.

- October has the Halloween Parade, where the high school float reenacts historical events like the Smallish Earthquake of 1905 and the Horne’s float is Emory Battis—the guy who ran the perfume counter—on it dressed like a druid. I wonder if we were meant to make an association with Dugpas or if I did that all on my own. Either way, between that and the talk Dougie Milford makes at the high school about “the restorative powers of terror and darkness,” it sure feels like inadvertent (?) magic ritual put on by the whole town.

- The entire section’s margins are left empty, except for October, where we see an illustration of Groucho Marx-inspired fake nose and glasses “disguise.” That, I assume what the joke is, constitutes what could pass for a Halloween costume.

Page 76: Lumberjack Feast

On the bottom half of page 76, we get an explanation of the feeding frenzy known as Lumberjack Feast, held the last Sunday of the month at the fire department. All we learn here is Big Ed can pack in the pancakes, and that you should call 911 for more information.

DINING

Page 77-83: Dining in Twin Peaks

Page 77 is a location shot of the Double R counter all the way to the back wall, including that giant ice cream cone.

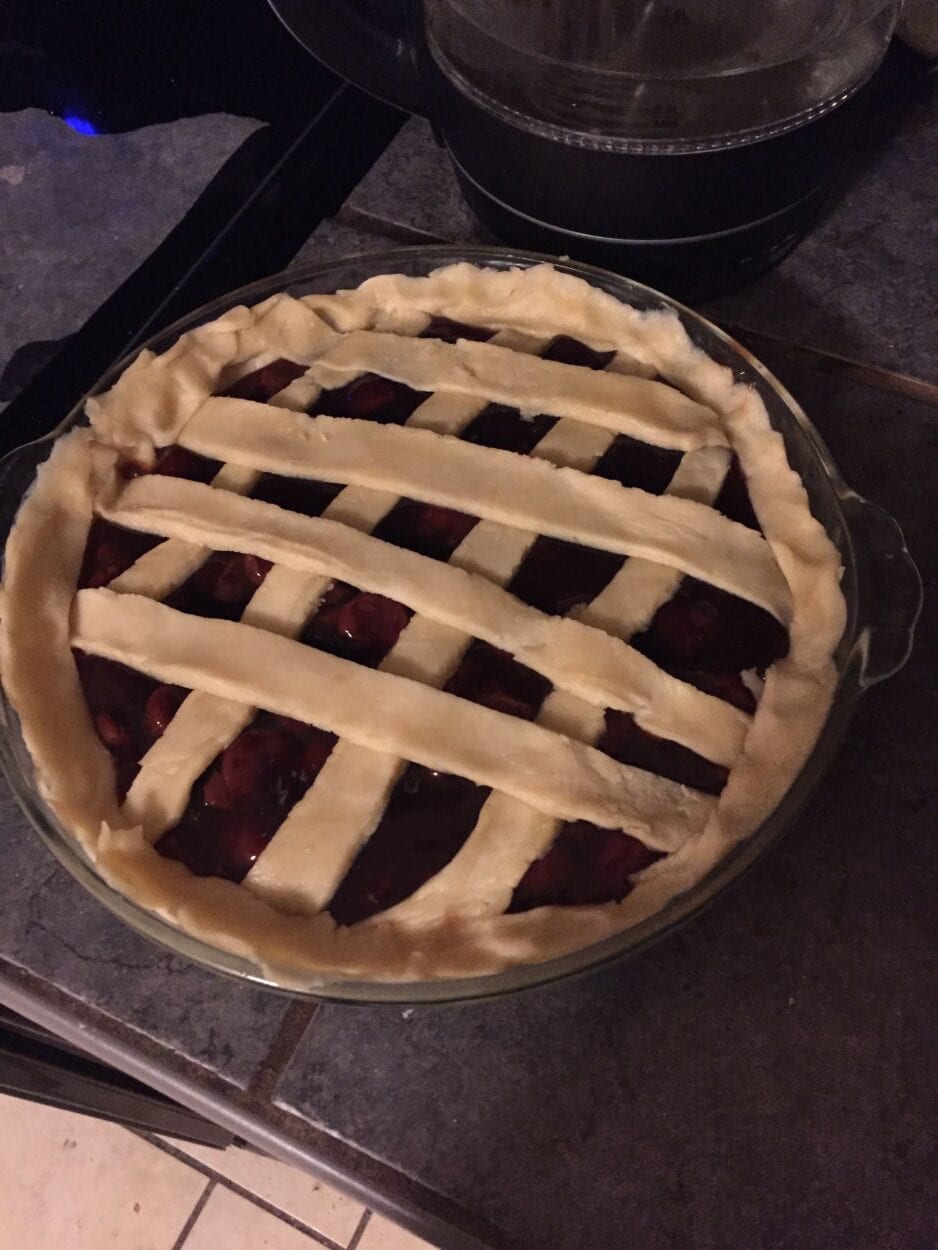

The page 79 margin features the Double R’s list of daily specials, but that’s not the draw here. Pages 78 and 79 make a two-page spread of Norma’s cherry pie recipe, which Rachel Stewart graciously baked for us here. Let’s see the results!

“This Pie is a Miracle”

Let me start by saying, I’m not a baker. I love The Great British Bake Off but I don’t envision myself ever getting a Paul Hollywood handshake. I do like to putter around in the kitchen, doing my best Nigella Lawson impression, making pots of soup or curry from whatever I’ve got kicking about in the fridge. (I can make Not Laura Moon’s Chili in my sleep now, which is helpful since I feel like hibernating most of the winter away.)

I love pie. I’m Southern, we have pie on any occasion—family reunions, weddings, funerals—but I’d never made a whole pie from scratch. And Twin Peaks Cherry Pie is the stuff of legend, so why not? Still, baking is like chemistry—there’s an exact science to it. You can’t chuck the directions out if you don’t like them.

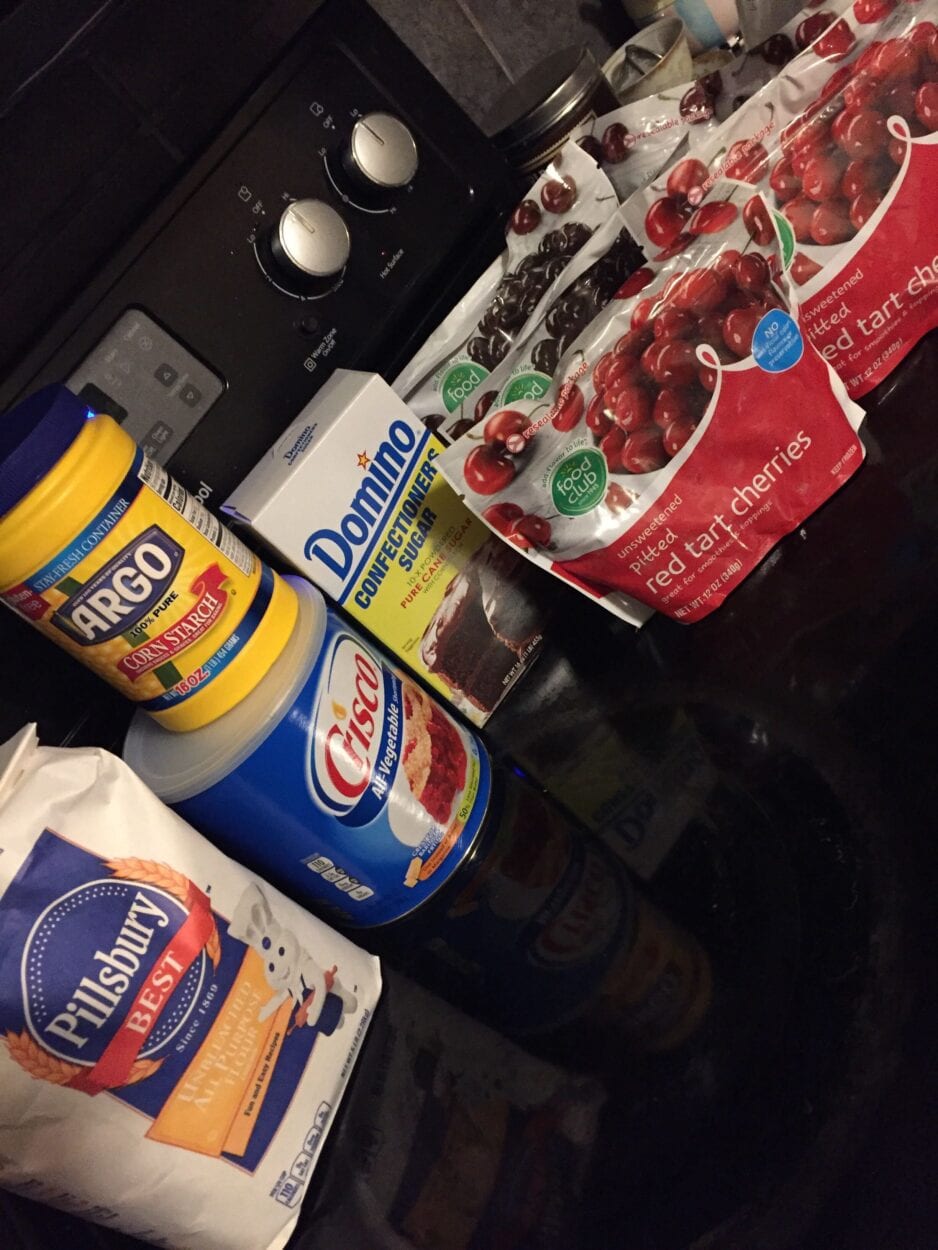

Luckily, the recipe requires some stuff to happen in stages (i.e. overnight) so I didn’t feel overwhelmed making it. First comes the crust, which is flour, Crisco, and ice water (added at the exact right time) mixed together until you have a ball of dough that can sit overnight in the fridge. The filling uses frozen cherries which you let sit out overnight to thaw, letting their ruby red liquor seep out for the saucy bit.

Once all the components have had their overnight nap wrapped in plastic, then you get onto assembling the pie. I tended to the pie crust first, then the filling, which came together quickly (despite having to wait for it to cool). My latticework was a rustic effort at best, but it smelled heavenly during the bake (maybe this is where pies go to die), and then it came down to the hardest bit yet: waiting for it to cool.

I made it the better part of the day and shared the pie with friends—and it was good. The cherry filling was tart and sweet, and the crust was buttery. Everything an FBI agent could dream of. The recipe note about adding more or less sugar is spot on, and if I ever make it again, I’d like to try it with dark cherries, which would warrant an extra spoonful of sugar.

I love how time and patience is an actual requirement for the recipe. It makes me think of mindfulness and the love Norma puts into it. Very on-brand, intentional or not. Thanks again, Rachel, for being our baker!

Pages 80 and 81 hypothesize multiple possible origins for Twin Peaks becoming so doughnut-crazy, but like everything else, there’s no definitive answer by page’s end. There are giant illustrations of a variety of doughnuts, and details about the Wagon Wheel Bakery—supplier of all those spreads we see at the Sheriff’s Station. Their doughnut recipe is listed here, but it’s for an order of 106 and none of us have a fryer set up so we couldn’t test this one for you.

Page 82 focuses on the Double R, both in its look and what’s on the menu. If I wasn’t already hungry, Norma Jennings’ bio is in the margin talking about things like her hallucinatory meatloaf recipe. Filed under cute jokes, Norma likes talking to Big Ed and believes in longer prison terms.

Page 83 contains a list of every song on the Double R jukebox. It leaves off any reference to Angelo Badalamenti songs, but otherwise, Reddit user oysterboy1 assembled a Spotify list of all the songs here.

Pages 84-85: Dining Out In Twin Peaks

Pages 84 and 85 present short descriptions of a half dozen local restaurants, as well as the Great Northern Timber Room’s capabilities and a nod to the Lamplighter Inn—famous for being mentioned in Dale Cooper’s first monologue. Also mentioned: fireworks expert Angelo Wong’s Italian/Thai Restaurant and Ace’s Bar-B-Que, both of which I’d love to try if they existed in real life.

Page 84’s margin shows Eileen Hayward’s Coffee For A Crowd—which “serves 40 to 250 servings.” As with the donuts, 25YL didn’t have the space to test that recipe. Page 85’s margin has James Hurley’s bio feature—where I note his lack of mentioning the Passion Play.

LODGING

Pages 86-89: Lodging In Twin Peaks

Pages 86 and 87 is an establishing shot of the Great Northern’s interior, complete with the famous lobby fireplace where Cooper and John Justice Wheeler shared their only scene while pontificating on love.

Pages 88 and 89 give us short paragraphs on the Great Northern Hotel, LeAnn’s Country Inn, Snow Street Inn, The Willow Inn, Pine View Motel—where Phillip Gerard stayed, and Ben and Catherine held trysts—the Cozy Box Bed ‘N Breakfast, and Mrs. Thrimble’s Bed and Breakfast.

Page 89’s margin includes a simple floor plan of the Great Northern lobby. But both pages 88 and 89 include the bio for Great Northern Employee of the Year Trudy Chalgrin. Why so much for a barely-seen character? Because this is one of those moments Ken Sherer was talking about when he said this:

[We] kind of knew this was the end, and so in some ways we wanted to try to personalize it for ourselves, that we were here.

Trudy is played by Jill Engels, wife of writer/producer Robert Engels. Good move including your wife, Bob! Jill not only played Trudy, but she also worked behind the scenes. Among other things, she sat just off-camera in the Red Room scenes and fed people their backward lines.

Next: Sports, Fashion, Religious Worship, Transportation, Town Life, and Government

SPORTS

Page 90-96: Football

Pages 90 and 91 present a picture spread across the middle of both pages. It is a high school yearbook photo of a football team with a list of names of those pictured. In regards to the writers adding personal touches, this photo is actually a genuine yearbook photo of Ken Scherer’s brother’s high school team.

Lines lead from 12 specific players in the team photo to their names and nicknames. The names include including Hank Jennings (the Lonesome End), Harry S. Truman (Quarterback, best completion record in the Tri-County area for two straight seasons), Thadiloniois “Toad” Barker (the roving defensive back), Ed “Big Ed” Hurley (stopped ‘em cold almost every time), and Tommy “the Hawk” Hill (Hero of the undefeated season). On the bottom, we get a list of all names pictured, and the margins have silly anecdotes about coach Bobo Hobson.

On pages 92 to 96, we get a breakdown of every game in the perfect season of ‘68, which would’ve been 23 years earlier. Five pages is a lot of real estate for any topic in this book. That’s quite the torch for a town to hold, especially when there’s no mention of today’s team. Thematically, this is another instance of being ruled by the past.

The season ended in victory when Hawk scores the final points on a ridiculously long fluke play. Ed Hurley said “the best thing in our lives, and we did it together.”

This would’ve been a fluff piece except for how Secret History of Twin Peaks changed all that. Much like how the Packards and Martells arrived in town in reverse order, we have some changes:

- The SHoTP team is the Lumberjacks. Here—and in Season 2—we have Steeplejacks.

- Here, the final play is a positive one performed by Hawk, culminating in a perfect season the town can’t stop celebrating.

- In SHoTP, the final play is a negative one as Hank Jennings intentionally throws the game, turning an otherwise glorious season into a trauma veiled in conspiracy the town can’t come to grips with. The one that got away.

FASHION

Pages 97-99: What to Wear

Page 97 seems to be included so the book could include “Mr. Richard Tremayne.” Though there’s no bio for him, the margin does contain something: The “Horne’s” logo in art deco font, which is quite classy.

Pages 98 and 99 include alternatives to Horne’s Department store: the utilitarian Ed Strimble’s Worker’s Warehouse, and a place that focuses on art and jewelry called Carlson’s Odd Shop.

I love the use of promo shots by Paula Shimatsu-u being credited as “locals”:

- Lynch and Frost, outside the sheriff station, conversing while working on the pilot.

- Dana Ashbrook (arms crossed and head held pompously high) and James Marshall (hands tucked in leather jacket and cheeks sucked in Zoolander style) flanking a totem pole looking serious.

Page 99: Furniture

The bottom half of page 99 is about the eccentric selection of local furniture. I’m curious if the two selections pictured were some props that Lynch built himself. At a minimum, they had to have caught his eye.

RELIGIOUS WORSHIP

Pages 100-101: Where To Worship

Pages 100 and 101 list places of worship. We learn:

- The Palmers, Briggs, and Jennings are Lutheran.

- The Hurleys, Pulaskis, and Packards are Catholic.

- The Haywards and Hornes are Episcopalian.

- The Theosophist Society notes appearances from Pete Martell, the Log Lady, and Agent Cooper.

There’s finally more listed about the Circulars (unmentioned since the Owl Cave entry) in the page 101 margin. It’s a tribe of “perhaps 50 to 62 members” who believe in the circular nature of existence, and also eating the flesh of fellow humans “to assume nobler aspects of their victims.” So strange.

I like page 100’s margin feature better: an illustration of a stag head with a cross of light between its antlers. It’s associated with St. Hubert, surprisingly a real thing.

TRANSPORTATION

Page 102: Transportation in Twin Peaks

Page 102 proves there’s little public transportation in the area—a bus that only stops in front of the Double R, or Tim & Tom’s Taxi-dermy (as long as you give them a day or two’s advance notice, they’ll be there).

Besides that, if you have a small private jet like John Justice Wheeler, you can use Unguin’s Air Force Base. The base is named after James Packard’s Lodge-adjacent wife from the town’s early days, a nice thematically-appropriate callback.

We get a picture of the sparse bus schedule, as well as a list in the margin of local radio stations. You can get country/western with a dash of All Things Considered, timber news and weather, old comedy programs, classic rock, bluegrass, CBC Radio Canada, and classical music. Yet again shut out is Angelo Badalamenti music we actually hear on the show.

TOWN LIFE

Page 103: Twin Peaks Gazette

Page 103 is a smaller version of the actual front page of Twin Peaks Gazette Volume 1, Number 1. There’s an actual order form at the bottom. I wish I’d paid the $29.95 back in the day to subscribe; I’d have a sweet Twin Peaks Sheriff’s Department mug.

Pages 104-105: Switchboard Operator

Page 104 has a story about how rogue original phone operator McFarley O’Halloran arranged the town phone book alphabetically by first name. Wurman, in his Twin Peaks Unwrapped interview, said Reykjavik did their phone books that way and he thought that was quirky enough to use in Twin Peaks too.

Page 105 has a selection of those names as seen in the phone book, probably chosen for the repetitions of Roberts (10, plus one Roberta).

Page 106: Twin Peaks Timber Players

Page 106 is all about the local theater troupe, which was founded in the ‘70s by Sarah and Leland Palmer. The troupe puts on three plays a summer in the school gym.

Doc Hayward’s bio is in the margin, due to the fact that his actor Warren Frost did this kind of job in Minnesota when his son Mark was growing up. Where else was Warren Frost’s character going to feel more at home in the Access Guide?

Hayward’s bests include the Passion Play. His bio also lists that Will is an expert in euthanasia. I assume that detail isn’t there to say he’s some kind of killer, rather it’s probably a nuanced way to say the Doc knows many ways to show compassion.

Page 107: Black Lake Cemetery

This page is all about the place where Leland and Laura Palmer are laid to rest. It’s the only time Laura’s name is used in the Access Guide but I’m glad they found a way to do it.

Leland’s bio is in the margin. We find out he’s an expert on international corporate law, which is probably what Ben Horne loves him for.

Page 108: Twin Peaks Chamber of Commerce

Page 108 gives us a list of items and their dollar amounts the Twin Peaks government spends its money on. There’s a category for Membership (corporate, individual, and delinquent) and the quantity of each. Then a category for Income (Miss Twin Peaks brings in almost half the annual revenue), followed by a category on Expenses.

The town’s at a balance of -$422,318.00, but only due to a pending lawsuit from sack race injuries at the 4th of July picnic. A joke about the perils of litigiousness?

The other joke is how Night Time Security is otherwise known as Sparky the watchdog.

GOVERNMENT

Page 109: Proposed Prison Facility

There’s a blueprint on Page 109 for a proposed high-security prison. Even back in 1991, the for-profit prison system has been on the mind of at least Mark Frost. I used to be so confused why this page was included, especially on the page with Harry Truman’s margin bio, but then it returns in a fully-realized way within The Final Dossier.

Who made this prison’s plans? DLMF Creations (read that as David Lynch Mark Frost). The page says a majority of council members shoot it down every year. “Sheriff Truman remains on the fence about the whole thing, but Ben Horne recognizes a business opportunity when he sees one.”

At the time, I bet the fight for this prison was floated as a possible replacement for the Ghostwood Development Project storyline back when the original Season 3 was being pre-planned. But today we know for sure that this now operates as foreshadowing for Ben Horne’s Final Dossier predicament.

As far as Harry’s margin bio goes, he’s fond of oriental dishes (another terrible pun, that hasn’t aged well), Wagon Wheel Doughnuts, and the Passion Play.

Page 110: Unguin Field Observatory

Page 110 is a reproduction of letterhead from the Twin Peaks Chamber of Commerce and Industry. It contained a draft of what they wanted to include in the Access Guide and was sent to Garland Briggs for approval. Instead of a standard reply, he sent it back to them with all the classified information blacked out. What was left? Six words, at random places on the page. They are “nobody,” “knows,” “the,” trouble,” “we’ve,” “caused.”

This is not only the last official story-related page of the book, but it’s also a nice way to tie back to the book’s beginning. The observatory’s abbreviation is UFO, and it is also named after the first Lodge-adjacent settler. It’s a nice symmetry to tie Unguin to Briggs’ current Blue Book-adjacent work.

It’s a shame the Observatory was repurposed into Listening Post Alpha for The Secret History of Twin Peaks, but with the books’ adversarial relationship being what it is, it’s par for the course.

Page 111: Credits

The top half of Page 111 is the list of people who worked on the Access Guide. Lynch, Frost, and Wurman are listed at the top. We get Scherer listed as the COO of Lynch/Frost Productions. We also get a list of Writers: Gregg Almquist and Lise Friedman (who appear to work for Access Press), and Twin Peaks writers Tricia Brock, Harley Peyton, and Robert Engels.

Then there’s a category for Project Coordination, Art Direction, Research & Production, Special Thanks To, and a note of thanks to Snoqualmie and North Bend.

The bottom half of the page is an ad for the Star Pics Twin Peaks Collectible Card Art that begs us to “RELIVE THE MYSTERY!” The 76-card set must’ve also been released around this time.

Page 112: Welcome to the World of Twin Peaks

The final page of the book consists of a mail order form for Simon & Schuster, where you can “check here” in a green box for The Autobiography of F.B.I. Special Agent Dale Cooper My Life My Tapes and/or The Secret Diary of Laura Palmer. Both are priced at $8.95.

The ad presumes you’re going to tear the page out of this guide, fold it up, put your address on the form, add a stamp, and send it out with the mail. Can you even imagine doing that?

The Inside Back Cover

The top third of the page is a map of highways. Twin Peaks is located just above and to the right of center, squarely between British Colombia, Washington and Montana. Missoula (home town of Lynch) appears, as does Yakima (home town of Kyle MacLachlan).

Below the map is a two-column chart of “Mileage, from Twin Peaks to…” A number of towns within Canada and the US are on the list, as well as odd ducks “Stockholm, Sweden” and “Hong Kong.”

Beneath that, the illustration of the town flower—the pine cone— returns next to the publisher info for “Pocket Books, a division of Simon & Schuster.”

The Back Cover

The map on the back is a painted, farther-away illustration of the map from the inside front cover. We can now see that Lynch Road goes beyond Low Town and dead-ends at Unguin’s Field Observatory.

We also learn that Glastonberry Grove and Owl Cave are near each other off of Blue Pine Mountain, a fair way away from the town proper, and that the train graveyard is due south of them.

The Great Northern is south of White Tail Mountain on this map, rather than in between the two mountains, so it doesn’t match with modern continuity. But as Peaks moves from one side of the state to the other, I’ll give this a pass.

Beyond this, the ISBN and bar code occupy the bottom of this otherwise green cover.

FINAL THOUGHTS

I didn’t have a copy of this book until 2011, and I had no idea what to expect from it when I bought it. What I got was a welcome, immersive Twin Peaks experience. I can’t help but adore this book.

Based on how this book was created while the team was simultaneously making Season 2 at the breakneck speed of network television production, I forgive its inconsistencies and applaud it for being way better than it had any right to be. A silly book of gags didn’t need to have the deep Twin Peaks core this book has at its center.

I thank everyone involved in its production for this unique way to feel what it’s like to live in Twin Peaks.

- Wrapped In Plastic Magazine, Volume 1, Number 9, Page 4