“Death is like taking off a tight shoe.” ~ Ram Dass

Ever since the pilot, shoes have been key players in Twin Peaks, as symbols for transformation and literal hiding places for keys and tapes. But then, in the summer of ’17, for the opening shot of Season 3, Lynch gives us a dramatic close-up of black shoes —reminiscent of the two black dogs that open Season 1. “Back to starting positions.” A single light caught in the shoes doubles like the headlights in Part 18; like owl eyes, like all the doubling. Stars align (especially when you pause the TV), and Twin Peaks symbol magic is already afoot!

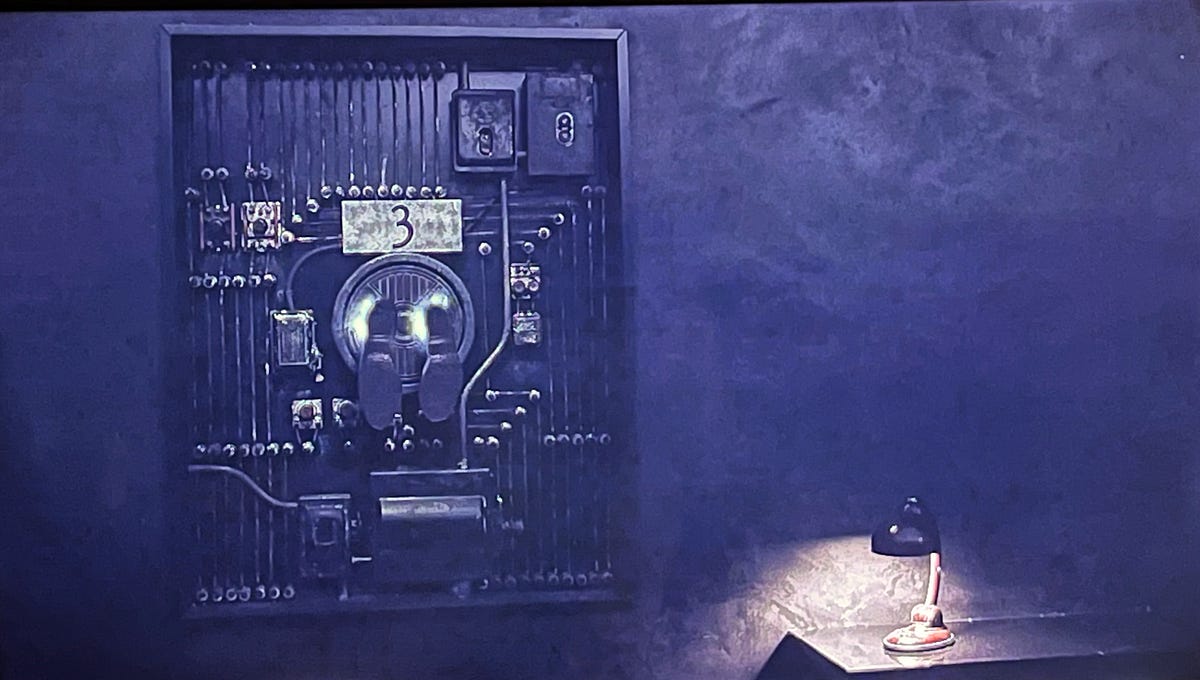

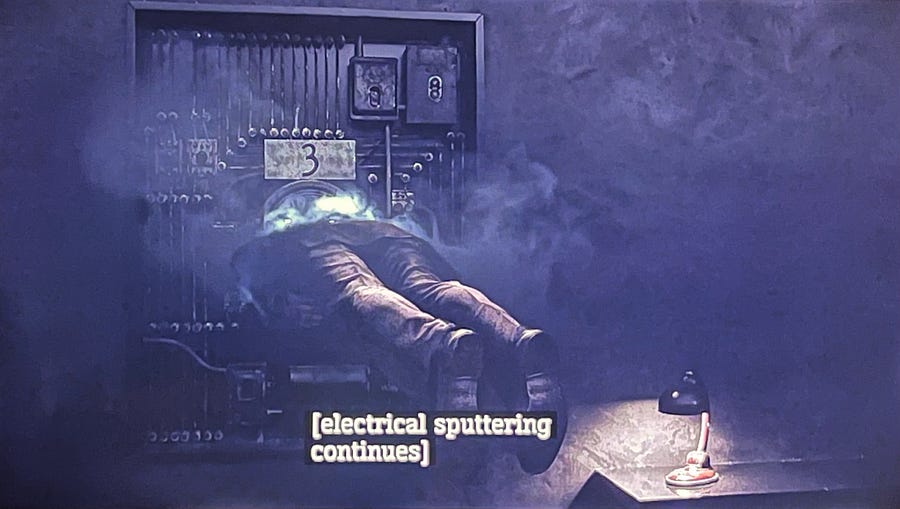

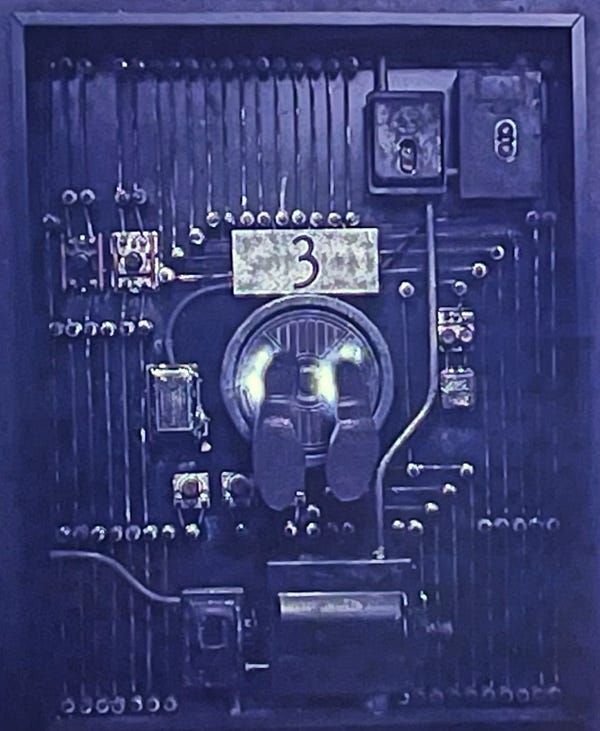

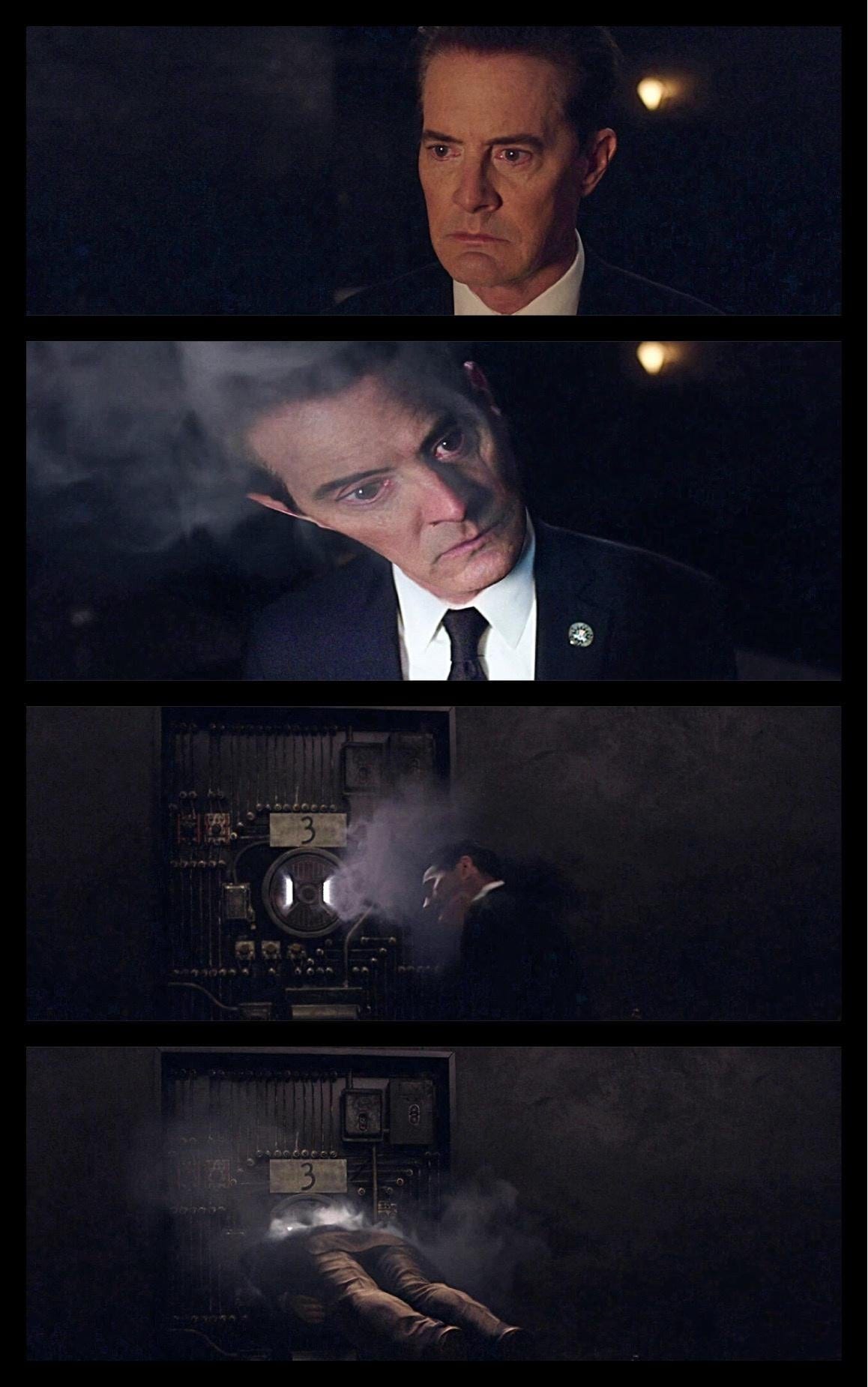

Then, can you believe it, Season 3, Part 3, beneath a big number 3 (Lynch loves his trinities), black footwear is all that remains of Dale Cooper. We witness Cooper’s shoes, mid-electrocution, hang on the wall in a frame like a work of art. They flicker, shake, then fall to the floor, landing face up, ready for their close-up! And they get one. This sequence is cartoonish, haunting, and is full of echoes from across the series and, lucky us, religion and art history. This is also a climactic moment when Cooper, finally, after 25 years, makes his exodus from the Lodge and back into the ‘real world.’

The shoes’ juxtaposition to vomit, electricity, and rebirth imagery in this moment suggests even deeper dimensions. Perhaps they are even placental like Spirited Away’s NoFace. My question is: did Cooper lose the shoes, were they stolen/forced off his feet, or did he leave them behind on purpose?

If on purpose, I suspect Cooper had good reasons. For example, the shoes might function as a supernatural walkie-talkie to the shoe salesman himself, Philip Gerard (manufacturer of soles and souls). Maybe Gerard puts them on his own feet to keep in touch with Cooper through sympathetic magic — a way to rival Mr. C and BOB’s connection. This theory transforms the shoes into magic objects like the ring, out of sync with time and space, able to transport people to Another Place.

Sole Searching

“The shoes are hallucinogenic.” ~ Jacques Derrida

Plugging the shoes into the outlet of art history generates interesting sparks. When we gather a dozen or so images, we start to behold what folklorist William Irwin Thompson calls an image cluster, like an image atlas. The imagination sorts through the major themes of a cluster until an archetypal signal appears.

One famous image that comes up is Jan van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait showcasing shoes in a dramatic way. Art historian Erwin Panofsky coined the term “disguised symbols” specifically to discuss the shoes in this painting. Especially in early renaissance art, shoes were symbols embedded within the domestic scene to transform the space into a repository of social customs and mores. On top of the surface narrative, they stage a different kind of story.

For example, the male shoes are black, in the foreground, next to the door, turned outward, while the female shoes are red and in the background, next to the bed, turned inward; They are silent actors, and their arrangement is their dialogue. The shoes point to dichotomies of gender, but also to the cycles of life: passing through doorways, lying down, sleeping, and then the final sleep of death — one candle in the chandelier is lit above her shoes, which suggests the subject has died or will die. The painting is allegedly proof of a marriage, yet evidently it was painted 13 years before the couple got married. The true and final “meaning” of the painting’s origin remains a mystery.

Waiting for Godot

The shoes’ theatricality finds a parallel in Samuel Beckett’s 1953 Waiting for Godot. In the play, one of the two clowns or “tramps”, Estragon, spends most of the time trying to remove his old boots that are causing him pain. When the shoes finally come off, they end up downstage center, looking kind of sad without their subject. The shoes evoke him anyway, especially in Beckett’s staging; our minds play tricks on us due to the gestalt principle of closure, and we “see” an invisible man standing in the shoes; a ghost. It’s interesting that Beckett in French means boots, and Godot sounds a lot like French words for shoes. (Note: Lois Gordon, in her book Reading Godot, offers a few explanations of the etymology of the name: Of a dozen common French words and phrases that begin with g-o-d, nearly every one has some teasing connection to shoes. “Godillot is French for ‘hobnailed boot’ or ‘shapeless old shoe’; and godasses are ‘military boots’”. Roger Blin, the director of the original production, said that Beckett told him the name comes from the French slang word for boot — godillot. See the Ruby Cohn Casebook). It also means G-o-d, which is why the original pronunciation (emphasis on the first syllable) is so important: God-oh is “Oh God” backwards. Not to take the absurdist, Dadaist quality of the word away; That it’s meaningless might be the most important “meaning.” Just like the made-up word “Godot,” the shoes in Twin Peaks can be a nonsense word, a TM mantra, perfect for meditation, not only because it empties the mind of meaning and movement, but because in doing so it provokes deep meaning, deep movement.

The Slippers

Another painting that features shoes is Samuel van Hoogstraten’s 1655 The Slippers. It depicts black leather shoes in the mauve zone of the painting, hiding in plain sight due to the patterned floor and tan rug. The left heal is crossing the edge, just like Cooper’s in Twin Peaks. In both images, shoes are left between rooms, and juxtaposed with keys, candle (lamp), door, chair, art, curtain, and broom — all symbols for domesticity and the sacred, all examples of Protestant heirotopy. David Lynch, like Beckett, Van Eyck, and van Hoogstraten, creates unsettling interiors through heirotopy. And I mean just look at the shared vibes. Is it just a coincidence that Hoogstraten’s 1655 Peepshow “perspective box” resembles the Twin Peaks Doorway Picture, and his Man at a Window resembles Cooper at the wall socket seen from reverse? It’s also giving Santa.

The Soul of the Sole

Shoes in many ways act as a symbolic foundation for our identities: We walk in someone’s else’s shoes, have big shoes to fill, and the type of shoes we wear can determine our social mobility. Zooming out for a second, shoes are one of our oldest technologies, really the prototype for all other tools that protect our bodies and allow us to travel difficult terrain. Shoes expand our reach. Professor Randy Laist explains that, in general form and function, our cars, boats, and rocket ships are essentially big shoes; spacesuits are whole-body shoes; vaccines are cellular shoes. Masks are face-shoes. Laist says even abstract concepts and artworks are shoe-like in that they separate us from direct experience to provide us with a new, heightened reality.

Shoes are valuable and collected. Some museums chronicle the transformation of shoes from clothing item to art object. They are also dirty, filthy, abject. Take them off! For detectives, they’re gold in missing persons cases because shoes are full of clues. Sadly, they can become the haunted remains of a person who stood at the edge and jumped (see barefoot suicide trope), and let’s not forget the cross-cultural practice of removing shoes before entering a sacred space.

The kinky thing about shoes and feet might have to do with human neurology. The areas of the brain dedicated to the feet and genitals are neighbors leading to neurological “cross-talk.” (See Encyclopedia Britannica illustration of the somatosensory homunculus). Mouth-anogenital, Soul-sole, Sky-earth, Above-below connect in the loop around the brain and landscape, and these connections shine light onto other strange folkloric twins.

What this all means is that the left and right shoes serve as symbols for the left and right halves of the brain, as reminders of the Hermitic axiom “As above so below,” and of our unique ability as humans to armor ourselves.

A pair of worn shoes

The ‘compound analogues’ isolated and framed in Twin Peaks connects first and foremost Vincent’s 1886 painting of shoes crackling with yellow ochre energy, probably the most talked about shoes in philosophy and art history. (For the best introduction, see Borrowed Shoes). In Vincent’s painting, the worn out black boots face forward, laces undone, surrounded by a nondescript space of yellow ochre (Lynch’s favorite color; See his 1996 painting Rock with Seven Eyes, staged like Vincent’s). Basically, in the 1930s, Heidegger saw a peasant woman’s life in the shoes, while Meyer Shapiro pointed to letters by Paul Gauguin, who lived with Vincent in Paris, and witnessed the painting’s creation. Gauguin reports that the old shoes were Vincent’s. He called them ‘relics’ commemorating a mystical experience Vincent had when he rescued a man from a terrible fire. (The yellow ochre?). After doctors gave the victim up for dead, Vincent spent forty days and forty nights watching over him, spending his own money on medicines and food to nurse the stranger back to life. During that time, when the burnt man began to speak again, Vincent reportedly saw and felt God Himself in a vision. “And I, Vincent, I painted him!” Vincent, who was a theologian for most of his life, painted God(ot), ultimate reality, ‘ultimate concern,’ as a pair of worn shoes? The light yellow is therefore a crude halo, and the shoes are a hieroglyph or divine portrait.

In the 1990s, Buddhist philosopher Ken Wilber expanded on Shapiro to explain why we should take Vincent’s mystical — perhaps hallucinatory — experience seriously.

Plot twist: Bloom and Hill say that upon closer inspection, Vincent’s shoes are two left feet — a “nonpair.” Whoops! The entire philosophical debate is based on a false premise. Sound familiar? And yet, two from one…this revelation transforms Heidegger’s imaginary peasant woman into a mismatched odd couple — perhaps Vincent and the sick man, or Vincent and Gauguin, whose roommate drama culminated in the famous ear incident. If objects stand for people, then yes, these are technically Vincent’s shoes, but also someone else’s. Nothing is fixed, not even the identity of worn shoes, and that is precisely what Lynch might be signaling to us with this scene in Part 3. Shoes, like masks, like identities, can be taken off. Bloom and Hill take Vincent’s shoes even further, comparing them to the fetishistic severed ear at the opening of David Lynch’s Blue Velvet. Fittingly, in the film, the ear belongs to someone obliquely referred to as Van Gogh.

Vincent’s visionary painting predicts the assisted readymades and pop art. Meanwhile, Magritte swoops in with his own surrealist response in The Red Model, staged just like Vincent’s but giving Godot and Blue Velvet. In 1982 John Berger chimes in with a damn fine Marxist-informed interpretation, that the shoes are a tribute to labor, and around that same time, Andy Warhol manufactures cosmic shoe paintings with diamond dust to make them just plain extra. Frederic Jameson uses Warhol’s shoes for the cover of his 1991 book defining postmodernism.

No wonder Derrida in his 1978 essay Restitutions of the Truth in Pointing [Pointure] called the shoes “hallucinogenic” (from the Latin “hallucinari”, to wander in the mind). Cooper’s shoes are the same. They express the funhouse mirror condition and dreaminess inherent in ever-sliding signifiers. They are hieroglyphs of unfixed identity.

1990s Sculpture

Legs and light meet in Twin Peaks and in Robert Gober installations. See his Untitled 1990 next to a still from Lynch’s favorite movie, The Wizard of Oz, of dead legs being sucked into a house. It’s worth noting that in 1974 Lynch created a short film about legs called “The Amputee”. Cooper’s legs resemble Gober’s coming out of walls, which helps us understand them in another way. Gober’s are typically clad in pants, socks, and shoes from another era — the time of the artist’s childhood, the mid-1950s and ’60s, just like Lynch’s. Lifeless skin made from bleached beeswax and individually applied strands of human hair peeks out from the sliver of space between the bottom of the pant leg and the top of the sock. “An unadorned icon of death-in-life, as intuitively alien as it is profoundly ordinary, which has retained its fascinating horror over the quarter-century since it first appeared,” says Hyperallergic’s Thomas Micchelli about Gober’s. The artist was originally inspired by an unexpected sexual experience: “I was in this tiny little plane sitting next to this handsome businessman, and his trousers were pulled above his socks, and I was transfixed in this moment by his leg.” Some of Gober’s wax legs have candles attached to them, turning the body into a vigil, into fire, while others have drains attached, adding another layer of meaning to both Lynch’s and the body in general. See also Gober’s unsettling sculpture of an ear that looks like it was cut right out of Blue Velvet, and his 1992 shoe made of beeswax and hair. which further turns shoes into a body part. See also Kiki Smith’s 2006 drawing, Home, of shoes attached to legs coming out of a cardboard box.

“I’m doing shoes because I’m going back to my roots. In fact, I think maybe I should do nothing but shoes from now on.”

— Andy Warhol

Take off your shoes!

There is a human impulse expressed in an ancient yet current Japanese shoe arranging ritual that happens daily in the mudroom genkan (lit “mysterious entryway”). My question is: Are we watching Cooper, and by extension the director, take off his shoes before entering the new Twin Peaks? Is it on purpose? The scene emphasizes the removal of shoes, resonating with other instances we doff our footwear: before bed; before death; before a beach; before a sacred space; before suicide.

In Exodus, the first thing the voice from the Burning Bush says to Moses is “take your shoes off.” Then, in a profound twist, after 40 years of leading his people, Moses himself becomes the shoes that cannot enter the promised land. Is this also part of what happens to Cooper? In many traditions, shoes are dirty, unholy objects, collectors of dirt, germs, and ‘bad spirits’. In the Jewish fairy tale, Moses cannot ‘return’ except through an extended notion of a ghost. Is this Cooper’s fate as well? Crossing The Return with Exodus reveals interesting moiré patterns. By having Cooper remove his shoes before his exit, Twin Peaks — the fictional place and real TV show — becomes both promised land and burning bush.

A footwear scene at the beginning of Exodus foretold the ending, and this gives us more insight into what the scene in Twin Peaks can represent. Simultaneously, Cooper’s shoes falling to the floor read as a dream transfigured tragic rose trope, especially because he’s leaving a young woman in trouble.

While Moses removes his shoes at the burning bush, Cooper removes his shoes at an electric socket. Is electricity the new divinity? Or is our world itself a sacred place, demanding we remove our shoes? Wait. Did Moses ever put his shoes back on?

Hidden shoes

Is the socket huge, or is Cooper really small? There are tiny people — fairies, brownies, borrowers — who live in our collective unconscious and use shoes for magic. In fact, people across Europe used to conceal shoes in the walls of houses and churches to appease or expel these supernatural beings; apparently, witches were drawn to the smell of an old shoe, would shrink down, crawl in, and get trapped. Are Cooper’s shoes intended to trap, or at least slow down, a pursuing witch?

Furthermore, creatures hide in shoes, and in Lynch’s world, people inhabit objects from radiators to door knobs to logs, and the camera’s focus on the shoes could suggest that somebody lives in there now. We know from folklore that there was an old woman who lived in a shoe. She had so many children, she didn’t know what to do. Was she a witch, or did the shoe represent something else entirely?

Woman in Trouble

The shoe moment cements Twin Peaks as a fairy tale, opening it up to more levels of interpretation, since fairy tales, like myths, are repositories for cultural knowledge and lost cosmologies. As Diane podcast notes, Cooper’s new shoes, Dougie’s shoes, are red, so we’re ditching black and white for color as we saw Audrey do in Season 1 and Dorothy do in The Wizard of Oz. Now we get the impression that this shoe scene is another one that connectsTwin Peaks to The Wizard of Oz.

The Mauve Zone arc also feels like a twisted blend of Cinderella and Rapunzel: A woman in trouble is hidden in a tower, terrified of her mother’s return. “You’d better hurry,” she yells to her Peter Pan prince, who came in through her window like BOB. Cooper, rushing out (or pulled out through magic), leaves his shoes like Cinderella at midnight. Phillip Gerard, the shoe salesman, is our fairy godmother. Diane also occupied this tower, and Redditor deadghostalive points out that Rapunzel is possibly inspired by Danaë from Greek mythology. “As coincidence would have it, Danaë does appear in Twin Peaks/FWWM, or rather a painting of her by Rembrandt, in the scene when Donna and Laura visit the Power and Glory bar — twinpeaksblog.” !!! In the German version, Rapunzel is the mother of twins. In our version, who are the twins or ‘gifts’ Cooper leaves in Ronette’s tower? The shoes.

Ronette Pulaski, called “American Girl” in the subtitles and credits — her nickname at One Eyed Jacks? — now has a piece of Cooper she can smell to bring back memories. Of course, Ronette smelling something Cooper gives her mirrors that horrible moment in Season 2, when Coop, without warning, forces her to smell burnt engine oil to reenact her severe trauma. What a sicko! Notice that in this fantasy, something Cooper gives Ronette takes her back to the smell of her rapist and would-be killer, which supports Tim Kreider’s theory outlined in But Who is The Dreamer.

Echoes of Season 1, 2, 3, and FWWM all come together in this fire-lit back room.

Reflecting Cooper’s condition in the antique mirror of Grimm, we can take this even further and see how Twin Peaks expresses a lost cosmology and newly emergent property in the evolution of consciousness. Akin to Tarot and I-Ching, these shoes falling to the floor can tell us about our future!

Conclusions

Few objects are as intimate and yet as overlooked as the shoes on our feet. All shoes are rituals, agencies, places, spaces, quasi-objects, parasites, and then there’s the Freudian connection; they’re our #1 fetish object right next to women’s underwear.

The shoe scene may be empty of inherent meaning, and therefore full of our projections and dreams; and if you’re not actively filling the container of your mind with spectacular worldviews, then what’s the point? Cooper’s shoe-drop resonates with folk stories like Cinderella, Rapunzel, and Moses at the burning bush. The shoes connote fairy tale time and, therefore, the deep subconscious, making the scene memorable and mythopoeic. The Mauve Zone arc holds a secret key.

Cooper’s shoes help turn Twin Peaks into a mythos. They are a hieroglyph for unfixed identity, and an example of Lynchian hierotopy. They connect the text to art history, philosophy, theater, folkloristics, as well as to religious traditions of removing shoes before entering sacred ground. The empty shoes there on the floor are more than a footnote; they mark the series itself as an evolving fairy tale vibrating across literal, allegorical, and cosmological levels of meaning we can put on or take off like out shoes.

Endnotes

- Cooper gets sucked into the socket like a coin into a slot machine. There is an English saying, “Papa needs a new pair of shoes!” and Catherine Spooner in Return to Twin Peaks (2015) reminds us that needing a new pair of shoes is a traditional gambling expression, foreshadowing Mr. Jackpots. The shoes falling are now coins coming out of the slot machine. Cooper is entering the world of Twin Peaks again, and that is itself a gamble. But the shoes are falling right-side up. A good omen. It’s like the coffee cup landed right-side-up at the Fat Trout Trailer Park. Lynch loves coincidences.

-

Cooper’s “two birds with one stone” could mean: I’ll leave my shoes to help convince Jade I’m Dougie and to keep me tethered to Phillip and the lodge. The shoes play an integral part in the safe handover to Jade. That they are missing and Jade finds only one pair in the house sort of ‘seals the deal’; the missing shoes help Cooper earn Jade’s trust.

- Some fans theorize they are hibernation objects. Briggs may have given Cooper the idea to leave his soul in his sole — homophonic dream logic — to wait for the optimal moment to strike at Mr. C, BOB, and/or Judy. It’s interesting that in Part 15, he returns to the socket in front of another motherly figure.

- Byzantine hierotopy is the art of creating sacred space by arranging disguised symbols in paintings and in actual rooms. Art historian Andrew Simsky (2020) outlines how the concept specifically refers to Protestant Christian sacred spaces made out of what he calls “spatial icons” or symbols that “were seen as windows opening out onto an otherworldly reality, or, rather, as doors opening up a two-way communication.” This sounds a lot like Foucault’s heterotopias, “spacial creations of an ‘other place’”. (See The Killer Whale In The Room for more about heterotopias in Twin Peaks).

- In 1931, not long after Freud’s 1927 vision, Salvador Dalí built Surrealist Object Functioning Symbolically, a sculpture that physically connects a woman’s shoe to milk, sugar, feces, and tiny drawings of shoes.

- “A pair of shoes can contain an entire universe.” ~ Scott Horton

- Cooper’s shoes remain like the magical remains of enlightened people who achieve the “rainbow body phenomenon” at death, transforming into pure energy. Their bodies “shrink” and sometimes even disappear, “self-liberate” into a non-material body of “light” (a Sambhogakāya), and for some strange reason that makes no rational sense, they leave behind their hair and fingernails. If the body is cremated, then crystal “pearls” miraculously emerge from their bones and become relics.

- If this microcosm recapitulates the macrocosm of Twin Peaks, then Coop dropping the shoes is the US dropping the bombs. Nuclear-nuclear, at the nuclear family level, we let in an evil comparable to the evil we let in on a subatomic level.

- Within the “Find Laura” hypothesis, the shoe removal symbolizes something from Laura’s primal scene. Cooper is Leland, taking off his shoes, electrified with lust. Or, Cooper being eaten by the socket is Laura’s fantasy of BOB getting pulled into the walls. The shoes left behind, in her fantasy, are evidence that BOB was there.

- In the Mauve zone, the shoes are all that remain of Dale Cooper. Supernatural detectives might find them and be as confused as we were when we found Dougie’s wedding ring inside of Brigg’s 40 year old stomach.

- They resemble a sort of beautiful and sad readymade, like Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s Untitled (March 5th) #2 — a pair of 40-watt lightbulbs hung on extension cords — “suggesting a pair of lovers in one shared point of illumination. Although they glow brightly in unison, one bulb will inevitably burn out before the other, reminding us of the transience of human relationships and the temporality of life. Its title commemorates the birthday of the artist’s partner, Ross, who died of AIDS in 1991.” Shoes are memorials, shoes are relics.

- We can reframe the shoes as ‘extensions’ of our bodies — extensions that, as Marshall McLuhan put it, require an amputation. What do we give us when we wear shoes, and what do we give up when we remove them?

- They help protect Cooper, then are suddenly removed from the body of the narrative, never seen or heard from again; In this sense, Cooper’s shoes are like Melchizedek, whose special ritual jump-started the entire Abrahamic revolution: they take us where we need to go and then disappear from the story forever.

- FWWM features David Bowie’s red slippers, probably referencing Dorothy, and there are Audrey’s red shoes (is Bowie, Audrey?). There are also red shoes at the police station Cooper sees before having a conversation with the flag and wall outlet in Part 9. This is confirmation, according to some fans, for the “shoe theory“, that Cooper will need to retrieve his shoes in oder to gain full consciousness. I’d argue that, it was not an accident that he left his soul in his sole: it was all part of the plan.

“It’s easier to put on a pair of shoes than cover the whole world in leather.” ~Shantideva

Review:

Top 12 shoes in art history related to Cooper’s.

1: Van Gogh’s.

2. Van Eyck’s.

3. Van Hoogstraten’s.

4. Beckett’s.

5. Magritte’s

6. Japanese shoe arranging.

7. Moses and Exodus.

8. Cinderella.

9. Wizard of Oz.

10. Barefoot suicide trope.

11. Concealed shoes/shoe magic.

12. Gober’s shoe and leg sculptures

Did I miss any? What other shoe stories resonate with Cooper’s in Part 3?

I’m going to compare Twin Peaks, and maybe this whole mystery of Cooper losing his shoes, to the story of Cinderella. The growing view of the series always seemed to be that it was about Laura’s abuse by her father, but even though I tried to look at it that way, it still wasn’t the right fit, and I became convinced of Leland’s innocence. Even with that conviction, I was still left with so many unanswered questions, my mind ran out several shoes, itself, running on and on about it. Only after S03, when I took the shoe off of the Palmers and put it on to the Hornes, did everything begin to make sense.

My belief is that Ben was really abusing Audrey, it resulted in a son: Billy/the grandson. Billy murdered Laura (really the American Girl) because he confused any woman he was sexually attracted to with the mother he loved, but also feared. Inside of the dream he fashioned to help himself cope and escape, Twin Peaks, Billy hid behind the morally upright detective Dale Cooper. When investigating Laura’s (an imaginary composite of his mother, his victim and himself) death, he was exploring and hiding away from his own history, one he forced on to his victim.

The series was always about Who Killed Laura Palmer, only it was a statement rather than a question. Everything was a piece of her killer’s psyche and Bobby was right when he claimed that they all had killed the woman.

Looking at shoes in the series, they help strengthen this theory. Shoes hardly have anything to do with the Palmers but rather the Hornes.

There are two significances for shoes within the world of Twin Peaks. First is their role as transportation. Shoes enable people to walk a longer distance over rough terrain. In this way, they also provide protection to the feet. Cars, a different transportation, were linked to BOB. His host was called a vehicle. It is my belief that BOB is really Ben Horne, the dreamer’s father/grandfather. That makes the people whom worked for Ben, and assisted his crimes, the woodsmen. Leo and Leland’s cars were often seen, Emory Battis’ work space was littered with car models.

Secondly, shoes are an article of clothing. Clothing prevents exposure. The adorning of certain clothing seemed to possess the wearer with the spirit of the original owner. Likewise, the mask, another article of clothing, hides identity.

So shoes are both transportation and a clothing that represents the spirit of the wearer or a disguise. Both in a way offer protection.

Cooper’s shoes falling off basically indicates he is not whom we believe him to be. Those shoes are a part of the FBI suit that represent his reputation as an upright and moral FBI agent. However, this is more or less just a mask since Billy, the real killer, is hiding behind this image. This ties in with what Laura/Carrie whispers to him in S03: “Don’t assume (that) nobody can spot your dark suit off but me.”

When his shoes fall off, as he enters the socket, we are given the indication that the shoes he has been wearing do not fit him. A layer of his protection has been stripped.

In FWWM, Laura struggles to put her stockings on as she juggles talking on the phone. Now, Laura’s difficulty could hint that this whole narrative the dreamer is weaving for her doesn’t truly fit her either. She’s also importantly on the phone when it happens. Navy slang once labelled phones as “horns”. It is after this scene that the angel in her painting disappears. Earlier she asked the angel if her father was abusing her. Now that she believes he is, the angel leaves. She is not right. The shoe doesn’t fit. When she takes the ring and rejects her dreamer’s narrative – BOB and Dale being two sides of this control freak of a dreamer – Laura retains her autonomy and the angel returns to her in the Red Room. She laughs and cries in relief, now knowing the truth: Leland really did love her (the Voice of Love) and wouldn’t hurt her.

When Cooper loses his shoes and appears at the house in Rancho Rosa Estates, it is revealed that his sock has a hole in it. This is unexpected for a man depicted as “perfect” and exposes something hidden. This also links him to the Hornes and the theme connecting them to the Trinity Test, BOB’s arrival/birth on Earth. Cooper’s sock has a hole. When Ben watched old family films, we saw his father digging a hole for the Great Northern groundbreaking and then passing his son the shovel to dig the next hole. Like the Trinity test, a bomb and another hole, this destroyed the natural order of the land. The large billboard announcing the development for the Great Northern is also echoed in the Rancho Rosa Estate sign. In the Pilot, Audrey created a hole in the styrofoam cup, which caused destruction. That also led to her going in to disrupt the Norwegians, whom were a part of her father’s plans for Ghostwood development. It is easy then to associate the Great Northern with Ben being abused by his father, while Ghostwood becomes his abuse of Audrey, his own child. In turn, Audrey abused the child she had with her father, her own half brother Billy. Audrey’s pregnancy inside of the dream happened after an explosion, another hole. This could form the trinity in question.

Despite its being linked to the devastation of nature, the theme of incest more naturally occurs within the Horne family plot, whereas it looks shoehorned into the Palmer family. And there we go again, shoehorns were once known as schoying hornes. An early maker of them was a ROBERT Mindum.

We can find another link between shoes and the Hornes when we examine the oft forgotten Teresa Banks.

Audrey and Teresa both make their homes at transient lodgings. Audrey was also known as the Queen of Diamonds, while Teresa works out of the Red Diamond motel. In the Return, Audrey refers to her story as that of The Little Girl Aho Lived Down the Lane. In FWWM a patron at Hap’s Diner refers to Teresa as a little girl. When Chet questions if he knew Teresa Banks, the man replies “I know shit from shinola.” It seems like a throwaway line, but shinola was used to shine shoes. Shinola was classy stuff and shit was worthless. Basically, he might be saying that Audrey, Billy’s mom, was the valuable real deal while Teresa, the substitute/decoy Billy fashioned for her inside of his dream, was the fake. Or it might just be the opposite, Teresa closer to the truth of his mother. Also important to note is Audrey’s pregnancy after the bank incident and Teresa’s last name. Both women were also materialistic. Teresa an outright prostitute and Audrey the spoiled little rich girl.

It is often overlooked but a painting of Danaë, a story of sex/pregnancy linked to riches, appears far earlier in Twin Peaks than just its appearance in FWWM. It can be seen when Cooper rescues Audrey from One-Eyed Jack’s, only it is Titian’s depiction “Danaë with Nursemaid”. Danaë was impregnated by Zeus when he took the form of golden rain. Ben Horne is the richest man in Twin Peaks and Audrey always seemed isolated to their home together at the Great Northern. Except for her excursion to her father’s brothel, that is, where she was trapped. Several other Titian paintings are seen on the walls of One-Eyed Jack’s, including The Fall of Man, Noli me tangere (Latin for Don’t touch me or Stop touching me) and Venus with a Mirror. I believe Cooper’s rescue of Audrey here depicts her son’s fantasy that he could have saved his mother from being sexually used by their father. It was when Ben was going towards Audrey in a sexual manner at Jack’s, reflected in the mirror and quoting a line from the Tempest about dreams, that Dale was shot. After this the supernatural elements came to the forefront. This could have been a defence mechanism for Billy because the truth was being too closely skirted, something the dream was meant to escape.

When Audrey phoned Coop from Jack’s, she is seen wearing her saddle shoes, against a red curtained backdrop like the Red Room. She tells Dale she’s in trouble, a euphemism for being pregnant. The underlying torment for Billy is whom his father really was.

Coop/Dougie becomes fixated on the boots of the cowboy statue, a statue Lynch based off of his own father. It is possible that Billy, before he knew the truth of his horrifying parentage, envisioned his father as the typical heroic cowboy, leading to how Harry becomes a surrogate father figure for Dale to work with. Jack Wheeler (note the first name, as well as his cyclical last one) and his gentlemanly wooing of Audrey represents this too. The place where Bobby played pretend with his own dad was called Jack Rabbit’s Palace. Jack and Coop shared a scene talking by a fire at the Great Northern, where Dale inexplicably drank milk from a cowboy glass. Jack artificially appears to aid in Ben’s redemption and to help save Ghostwood, when Ben has a change of heart and wishes to save it.

Inside his office, Ben once took off his shoes before facing Jack, emerged in a conversation where he confessed “But at the end of the day when I look in the mirror, I have to face the fact that I really don’t know how to be good.” and asked for Jack’s help. Part of Jack’s advice was to tell the truth.

After Jack left town, Audrey was seen sitting barefoot in front of the fire in her father’s office. When Ben came in and saw her he commented that she made the rest of them all look like primates. This might answer the mystery of the monkey in FWWM and Billy’s own feeling that no other woman compares to his mother, another cause for him to kill the women whom remind him of her and then fail in being her. During this scene, where Audrey is barefoot and thus exposed, father and daughter discuss the Twin Peaks bank and how the Miss Twin Peaks contest will focus on preserving the environment and how they can relate it to saving Ghostwood. Audrey’s civil protest at the bank directly leads to her pregnancy which then is echoed all throughout Part 8 in the Trinity scene and the impregnation of the comatose girl with the frogmoth. Meanwhile there is a direct connection Lynch is trying to make between the violation of the environment and familial sexual abuse.

In his dream, just like Jack Wheeler, Billy sought desperately to repair his broken and wounded family.

When Mr. C alters the prison monitors there is a video of a shoe repair shop. When Cole and the gang are shown Mr. C’s arrest report William “Billy” Hastings is mixed in with it, including the mug shot showing a height chart indicating he was Hastings height. However, a shoe repair shop also indicates tools and those tools can lead us directly back to the indication of the trauma in the Horne family. While engaging in sexually charged flirting, Jack referenced something he heard Audrey’s grandfather say “if you’re gonna bring

a hammer, you better bring nails.” When Richard, Audrey’s son, hits and kills the small boy, the only thing in the back of the truck he was driving is a Knaak Construction Box, meant to keep tools. A hammer was seen in the train car where Laura was supposedly killed and yet in FWWM a knife is shown causing her death.

Everything leads back to the Hornes

The first shoes which are focused on in the Pilot are Audrey changing from saddle shoes to red heels. The black and white saddle shoes she wears at home. The red heels she changes into at school (while smoking) hinting at a double life. Before Laura’s heart necklace, there were Audrey’s shoes. Inside of the locker she keeps the red heels in, she also hides a Smokey the Bear ashtray. Fire and woods were associated with BOB and abuse. White, Black and Red, the colors of Audrey’s shoes, echo the color scheme of the Red Room. Granted the floor of the Red Room is sometimes brownish, and the white sometimes creamy, but over time the black of a pair of shoes fades to brown and the white becomes yellowed, perhaps the dreamer associating it with the passage of time/youth and his mom. Audrey’s first two appearances are related to school – going to and being at – so the shoes can even be tied to William “Billy” Hastings role as a high school principal. The start of S03 focused on Twin Peaks High’s corridors etc…

At the police station in Vegas, Dougie Coop’s attention is attracted to a pair of red heels, like Audrey’s, which lead him to a wall socket, like how he lost his own shoes.

Later, wearing red shoes, Janey-E, whom is as much Dougie Coop’s mother figure as his wife, adorns a pair of red shoes before seducing him. She is on top of the submissive, almost childlike, Dougie Coop. The scene is later echoed between Diane and Cooper in Part 18. The two have sex in a motel as the song My Prayer is heard. Audrey Horne once said a prayer and she lived in a hotel. Diane’s distress during the act could very well be her discomfort that Dale is picturing her not as herself but rather as his mother, Audrey Horne, while she is seeing him now as Audrey’s son, Billy, leading to Linda’s confession she no longer recognizes him. After the act, Dale Cooper becomes Richard, the name of his BOB possessed doppleganger’s son with Audrey.

Which leads us back to Richard and the importance of another Horne family member in regards to shoes/feet: Jerry, brother to Ben, uncle to Audrey, Grand uncle to Richard.

In Season 3, while lost in the woods, Jerry has a confrontation with his foot that claims not to be his foot. He eventually wins over it and escapes the woods. This easily mirrors MIKE’s relationship with his arm and when MIKE went so far as to cut it off because of its murderous connection to BOB and the control BOB had over him. Ben likewise controls his brother’s movements, constantly sending him away on business. I believe, Ben sent his brother away so the man would not see that he was abusing Audrey. Only when Jerry escapes from the woods is he closer to seeing the truth. It is then he witnesses Richard, Jerry’s own grand nephew’s, destruction at the hands of his father. He doesn’t see it correctly through the binoculars, however, representing how Billy’s uncle failed to see how Ben was destroying his own family. However, now Jerry takes responsibility for his blindness, blaming his binoculars on the murder when the police find him. He is naked when found, connecting him to MIKE’s spiritual rebirth. Also note how it is a policeman called Williams whom makes the call about Jerry to Ben.

BOB and MIKE were partners, very much like Ben and Jerry. The only being BOB feared was MIKE. Likewise, I believe the only person Ben probably feared was his brother Jerry, for he knew if Jerry discovered he was abusing Audrey he would make him stop. Ben would either be forced to stop, which he didn’t want to do, or hurt the brother he loved.

Jerry’s connection to Phillip Gerard/MIKE, whom was a shoe salesman, leads us right back to footwear and Ben again. Leo bought a pair of Gerard’s Circle Brand boots and then hid inside one of them a tape of Ben discussing starting a fire. Leo was seen wearing a Chevron patterned shirt as he was fooling around with those boots. He alerted Bobby to the tape by saying “New shoes” reminding Shelly he had taken a pair of boots in to be repaired. Bobby then used the tape to become a worker for Ben, strengthening the theory that the woodsmen represent Ben’s legion of helpers.

One of whom, of course, was his lawyer Leland and whom leads to another odd connection between shoes and the Hornes.

At Leland’s wake, Audrey Horne was inexplicably sitting with Sarah Palmer and Eileen Hayward. Why not Betty Briggs sitting with the two other moms? Or Donna, whom was Eileen’s daughter and Sarah’s daughter’s best friend? Seen through the eyes of this theory, Audrey had to be there for it was her son, and not Leland, whom truly murdered Sarah’s daughter, and that son was called Billy, the name of Eileen’s husband, the only William in the original series. Billy also framed the father (Leland) of Laura/American Girl for her death. How does this tie in to shoes, you might ask? At the same wake, Nadine Hurley, now reverted to a woman-child, is obsessed with the reflection in her highly polished shoes. Reflections/mirrors play a huge role in Twin Peaks and here Nadine mixes them with the theme of shoes.

I’ve already mentioned mirrors a few times here, with Ben’s quote about being good and looking in the mirror and knowing he’s not, the reflection of him walking towards Audrey at One-Eyed Jack’s and the painting of Venus with a Mirror hanging on the wall of his brothel.

I also believe that the Venus with a Mirror holds special significance for Twin Peaks as a whole. People assume Audrey didn’t meet Billy when she went to the Roadhouse. But she did. Billy was the mirror. In the painting, Cupid, Venus’ son is shown holding the mirror for his mother to look in to. Interestingly, the painting is seen in Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho, a film famously depicting a psychotic motel boy’s incestuous relationship with his own mother. It appears under the taxidermy of an owl there. The owls we see in Twin Peaks are Great HORNEd owls. The Hornes lived at the GREAT Northern. Psychopaths mirror other people, showing them what they want them to see, but having little personality themselves. While being questioned for Ruth’s murder, William Hastings constantly looked to the 2 way mirror, aware the police were watching him and trying to reflect back to them what served him best. Catherine infact summed it up best while describing Josie: “I think that early in her life, she must have learned the lesson that she could survive by being what other people wanted to see, by showing them that. And whatever was left of her private self, she may never have shown to anyone.” The first character we see is Josie staring at herself in a mirror (Billy) and she is also the one to punish Cooper by shooting him after his failure of leaving Audrey at the mercy of her father at One-Eyed Jack’s.

Which still rang too much of home for Billy.

Which reminds me of Ruby, a young woman at the same Roadhouse where Audrey sought Billy (whom hated the place). Ruby waits there for someone whom never comes to meet her, while her name invokes the pair of red slippers meant to take Dorothy home. When forcefully removed from her waiting place, Ruby begins to crawl through the dancing patrons, staring at their shoes. She crawls to the song Axolotl, which in itself invokes a creature stuck in a juvenile state, from a species that is highly incestuous. Eventually she breaks down, screaming. While obsessed with taking Laura home, Dale Cooper seems adverse to the idea of going home, himself, all while his Doppleganger states he never really left home. When confronted with the threat of going back home, the Doppleganger vomits up copious amounts of pain and sorrow mixed in with oil, showing what home means to him. The main entrance to the Black Lodge is found in Ghostwood. Once again consider Ghostwood as the allegory of Audrey Horne’s abuse by her father, and the gateway representing the birthing place of the son she conceived by him and then unleashed on the world.

At the end, Laura, as Carrie, even suggests Cooper has the wrong house, when he comes looking for her, outright suggesting that he needs to find “him”. Very likely the same mysterious and missing Billy, the son of the Little Girl Who Lived Down the Lane.

What Dale Cooper really needs to do is go home and face the horror of what happened inside of his own family not the family he is projecting it on to, and destroying in the process, like a foot being forced into a shoe that wasn’t meant for it. Ultimately, the shoes have very little to do with the Palmers but figure in with the Hornes of Twin Peaks far more.

And, as the saying goes, if the shoe fits, wear it.