This would look nice on your wall.

It is in our house now.

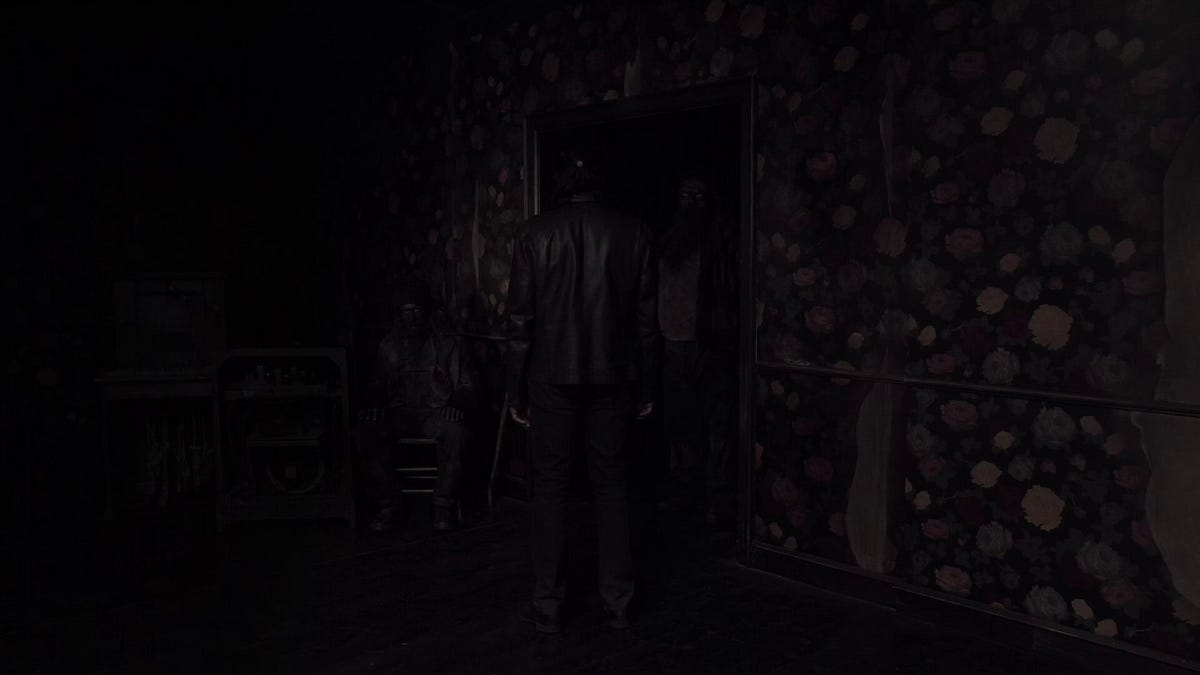

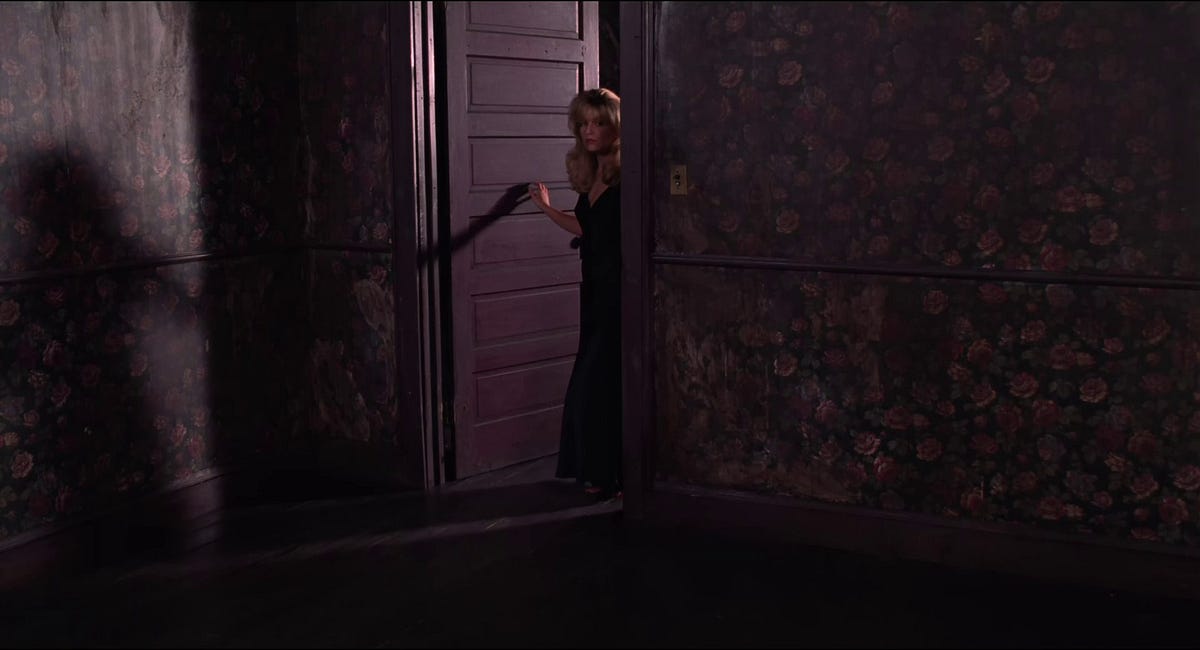

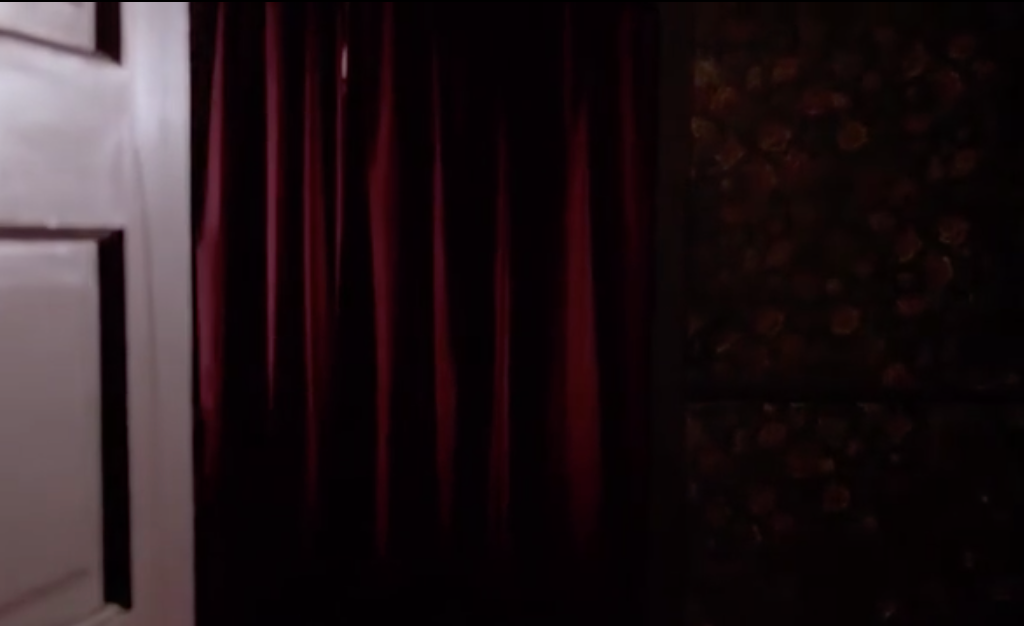

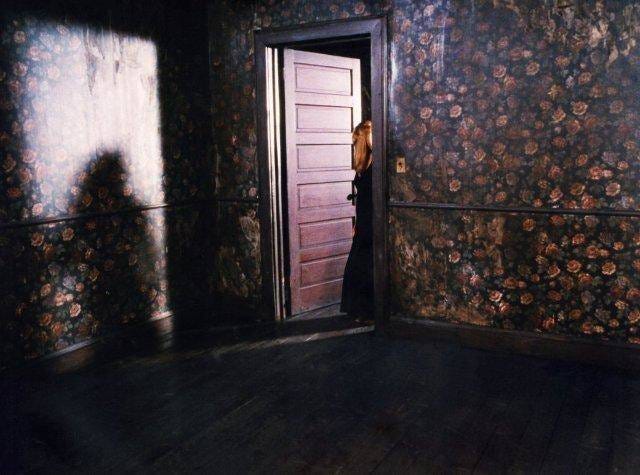

Twin Peaks spotlights an entire cast of other-than-human characters, curiosities like rings, rings, rooms, outlets, a ceiling fan, a telephone pole, and, as stated in the script, “a picture of a room with flowered wallpaper and a dark doorway in its corner.”

It is positively unsettling, probably because turning objects into people is a reversal of what Western civilization usually does.

She is my cousin.

Like Laura’s homecoming picture, the Doorway Picture now stands for the entire show—not just the picture, but also the empty room and its wallpaper. Similar wallpapers appear in all three seasons, but this Victorian red and pink roses on black is from Fire Walk With Me. It’s iconic, vintage, stained, and peeling.

Let’s look deep into the cultural and material histories of wallpaper, flowered wallpaper in particular, and so-called “wallpaper effects,” and then line these stories up in the imagination with themes from Twin Peaks and see what happens. We may find new patterns, new problems, and new mysteries.

After all, the very goal of wallpaper design, according to the master himself, William Morris, is “to attain a satisfying mystery, which is essential in all patterned goods, and which must be done by the designer.” Sounds like the goal of cinema and the goal of life in general.

Wallpaper Effects

Many disciplines use wallpaper metaphors so there is a bouquet of “wallpaper effects,” all of which can be felt in Twin Peaks.

In education science, the term refers to moments when data obscures reality and administrators become blinded by spectacular information like graphs, charts, and numbers. It’s a form of ocularcentrism and a (con)fusion of map and territory. Visual data wallpapers reality.

In sociology, the metaphor is used to describe intergroup contact and minority versus majority “constellations.” The “wallpaper” refers to someone’s daily life which can be “minority-dense,” and this affects one’s interactions with, and experiences of, the “other.”

In psychology and the humanities, the “wallpaper effect” generally refers to our pattern recognition skills and to Gestalt principles of perception like closure, continuity, proximity, and similarity. They’re activated not only while looking at walls but also while perceiving patterns in our minds and lives, which is why we also have Gestalt psychotherapy.

Moreover, the brain and cognitive sciences use wallpaper imagery to describe how the brain enacts and manufactures patterns it perceives. It’s always judging, organizing, and sorting. Henri Bergson: “Perception is never a simple contact of the mind with the object present; it is completely impregnated with memory-images which complete and interpret it.”

In other words, wallpapers point out that perception is less like a mirror, and more like a dreamer.

It can be quite mesmerizing. Shapes fit together like an M.C.Escher tessellation. Sometimes opposing volutes and kaleidoscoping symmetries lead the eyes off in opposite directions. We can flip figure and ground, or group different shapes together. We can take a step back to perceive the pattern across an expanse of wallpaper, and then, right before our eyes, the pattern changes.

Our eyes judge too, and our choice of pattern can change. Understanding Twin Peaks feels the same way, doesn’t it? Our choice of pattern can change.

Finally, “wallpaper effects” refer to moments when things and people disappear. Eventually, inside a house, we overlook the wallpaper as we chronically over-look our own noses (the Troxler effect), or like how we overlook the surface of a mirror. Anything that remains unchanging for an extended period of time is pushed into the background or even disappears from awareness completely (see Drew Leder’s The Absent Body).

This is why Indigenous American philosopher and art historian Nancy Mithlo uses wallpaper imagery to describe our racial biases. They are distortions that we overlook when interpreting the world, “everpresent and yet invisible.”

This is where we live, Shelly!

In the framed picture, a brownish-red door opens to another room covered in the same wallpaper. It appears these rooms are part of a Victorian-style house that connects different lodge spaces or “junction points” together into a structure some like to call the Black Lodge. We never quite know what this place is called. We do know that some of these rooms and their wallpapers are entoptic and follow us around. They are “inside” as well as “outside.”

How and why Mrs. Tremond takes a picture of this interdimensional space and frames it for Laura is never explained. Does she have pictures of other empty rooms? Is she some kind of interior decorator? The matting of this picture is horrible. Would it really look nice on Laura’s wall?

When Mrs. Tremond says, “This would look nice on your wall,” is she talking about the picture, the wallpaper in the picture, or the Black Lodge itself? Perhaps we are dealing with some sort of hypostatic union between all three.

Finally, where is the picture now? Did it disappear when Laura died like the owl ring or is it still in the house with Sarah? Maybe it’s the gate through which Alice Tremond entered the Palmer House! Is Doorway Picture also some sort of horcrux?

In/Different Spaces

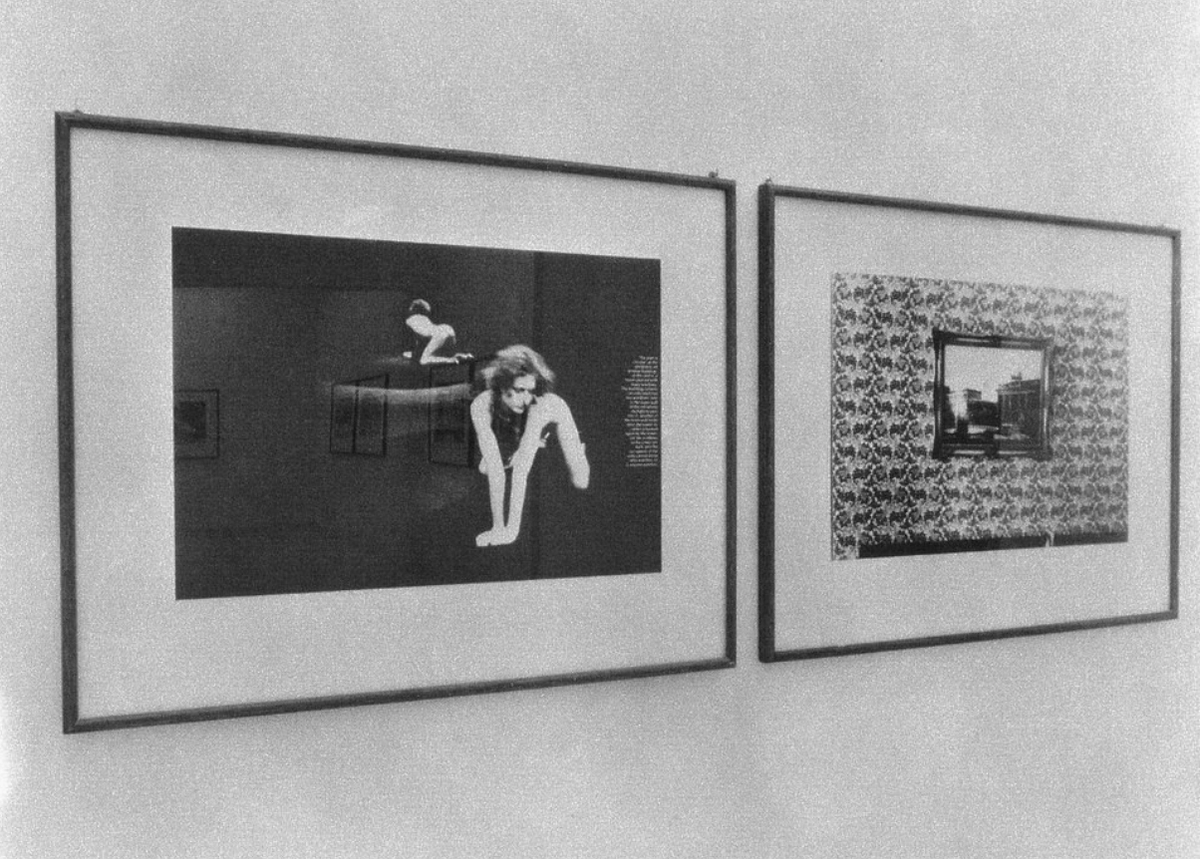

Speaking of gateways, before we get too far into it let’s not forget the glass and wooden frame. Art theorists like to point out how framed pictures (as objects of technoscience) always already have power and significance. It has something to do with the window quality, how they behave like gateways, portals, and peep-holes. They lead to Sartre’s keyholes, the male gaze, and “the Look of the Other.” Like framed mirrors, they orient the self, open up space, and reinforce “scopophilia.”

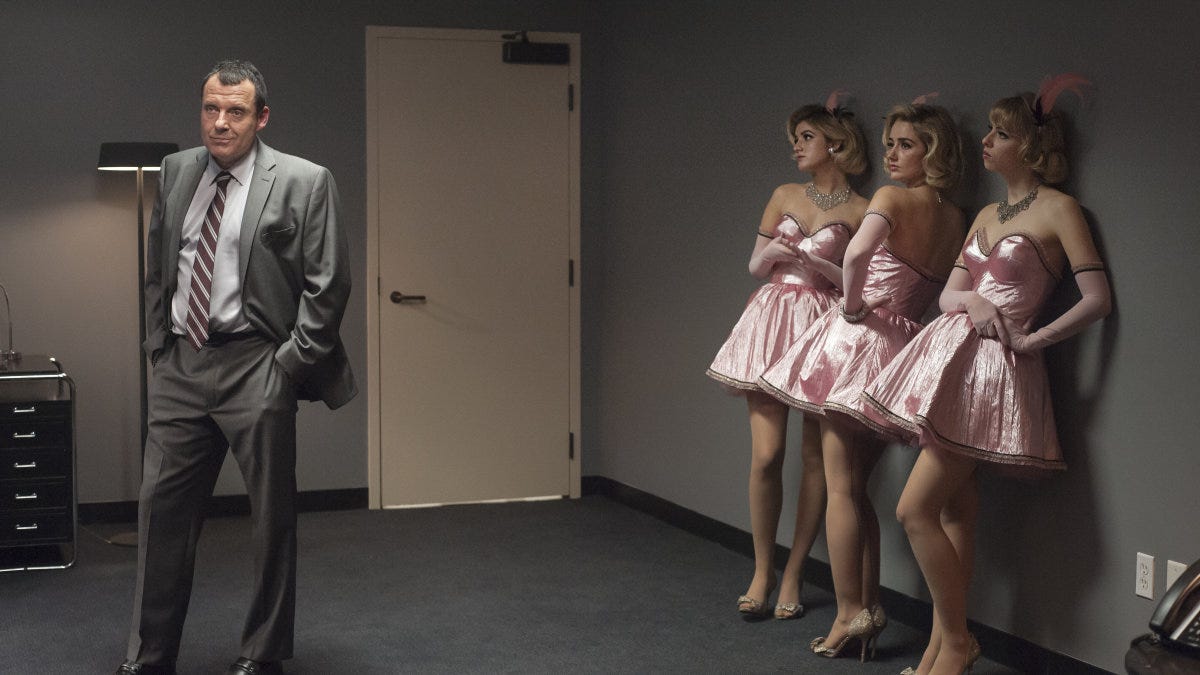

To illustrate this theme, curator Kate Linker in Representation and Sexuality looks into the 1978 framed diptych by Victor Burgin called Zoo 78. We see two black-and-white photographs matted and framed. The one on the left “cites/sights” a young, naked white woman on a revolving stage surrounded by dark surveillance booths. We are looking at her through a peep-hole. The other framed picture is of a framed picture of the Brandenburg Gate against a busy, floral wallpaper. Frames, gates, women, wallpaper.

There’s more. The text on Burgin’s photograph is a description of Jeremy Bentham’s panopticon, that innovation in prison architecture later described by Michel Foucault in his 1975 book Discipline and Punish. (The important insight is that nobody has to be in the observation tower for it to be effective).

Both Lynch and Burgin play with links between female bodies, doorways, and the “voyeur’s sadistic drive.” Burgin even links his voyeur-dreamer to television and electricity. When talking about the distracted spectator coming home from a look around the neighborhood, Burgin says, “Returning from this casual act of voyeurism they may “zap” through channels, of “flip” through magazines….”

Burgin also says framed photographs “(con)fuse” optical space with psychical space, or real objects with dream objects.

What Is Going On In This House?

Wallpapers are said to reveal the soul and character of a room. In settler America, they were also meant to help women communicate their taste, class, and the moral standing of their families. She was in charge of curating an artful experience at home that could lead everyone to a profound sense of harmony and spirituality. At least that’s what the magazines and paperhangers were saying, and advertisers still claim wallpaper will “fix your walls.”

People used to hang wallpaper like they used to hang textiles, without glue, and some old houses still show all the tack holes. In parts of the world, people replaced the textiles on their bodies with paper, too. Rayon, ersatz, and clothes made out of wood products further blend women into rooms. Let’s reconsider Josie’s fate as a wooden doorknob.

Josie, I see your face.

A constellation of meanings, resonances, and neurochemical changes is activated by layering metaphors in the imagination. Archeologist Ian Hodder in his book Entangled (2012) uses the term resonance to describe a subtle “coherence” of meanings and behaviors that occurs “across domains in historically specific contexts,” but usually on a nonverbal, nondiscursive level. Subconsciously, subliminally, doorways resonate with body openings, and floral wallpaper patterns resonate with underwear, lace, curtains, and bedspreads. (See Guda Koster’s art installations).

But it’s also, according to the literature, an extension of a woman’s personality. Historian Jan Jennings: “Wallpaper was a powerful material… Through wallpaper, a woman could make her own internal landscape, and it could be as wild and colorful as she likes because it was expressing a vitality of her spirit.” The outside may have to be dull, but the inside can be wild!

Let’s keep in mind Marshall McLuhan’s point, that every extension requires an amputation.

Them

And let’s also not overlook class. The new Lynchian horror TV show by Little Marvin, Them, and Charlie Kaufman’s I’m Thinking Of Ending Things both lean heavily on wallpaper imagery to signal race, class, artifice, fragility, gender, psychosis, loss, memory, hope, and home.

“It’s there when I sleep. It’s there when I wake up. It’s always there. Always.”

Wallpaper scholars point out there were classes of papers and classes of installers who were almost always men. We don’t know much more about them because apparently the trade was neither large enough nor organized enough to have left a trace in labor history. A secret guild? I wonder if they were queer.

Who do you think wallpapered the Black Lodge, and did they also pick out the lamps and curtains?

I tried to keep a clean house.

Wallpapers are mediums, and we know they have agency, not just in their effect on our bodies and emotions, but also in how they work to structure memory, class, race, and gender. Contemporary artists also demonstrate ongoing social, psychological, and spiritual dimensions of the medium. It’s no surprise that the heavy themes repeated in US contemporary art galleries relate to themes in Twin Peaks because Lynch and Frost are geniuses, and Doorway Picture can be seen in context with its contemporaries, whispering and resonating.

New American Wallpaper

As cultural historian William Irwin Thompson puts it, artists are the journalists of civilization, but they sometimes talk about the news in 500-year cycles rather than just the day-to-day events. Wallpaper designers still record and repeat images from their environments, but now, on top of the flowers and toile, we get Bible passages and pills (Damien Hirst), car crashes (Flat Vernacular), genitals, lynching and sleeping (Robert Gober), slavery and rape (Kara Walker), mushroom clouds and cows (Andy Warhol), the interracial queer-erotics of Native American drag queens (Kent Monkman), fake totem poles and Indigenous survivance (Nicholas Galanin), cigarettes and tits (Sarah Lucas), school bullies (Virgil Marti), Hitler and Duchamp (Rudolf Herz), handcuffs, surveillance cameras, Twitter birds, and the global refugee crisis (Ai Wei Wei), pixilated plants and file corruption information loss (Joiri Minaya), FBI surveillance materials and her father (Sadie Barnette) (!), dilapidated homes in her Kansas neighborhood (Yoonmi Nam), lowriders and roses (Nanibah Chacon), and links to ongoing histories of black and brown bodies (Kehinde Wylie).

Nick Cave transforms 2D wallpaper patterns into 3D “sound suits” and projects tiny abstract films onto old walls like wallpaper. In his installation Hy-Dyve, which took place in an abandoned church down the street from my house in Kansas City, movie projectors made the floor look like water rapids, and spectators were dwarfed by a giant wooden lifeguard chair surrounded by filmic wallpaper.

Rodney McMillan hangs stained carpets soaked with the funk of life from real American homes onto walls to be admired like wallpaper. Japanese art star Yayoi Kusama obliterates herself and her sculptures with red polka-dot wallpaper (and remember red dots mean something specific to Japanese people). Guda Koster’s installations magically lose the edges between wallpaper, clothing, houses, and heads. Francesca Woodman hides her naked body in an old house with large sheets of peeling floral wallpaper.

“Interior decorating with a vengeance.” ~ Dave Hickey

Ekphrasis

Writers work with wallpaper. In English literary history, wallpaper is a rhetorical space or storytelling device like ekphrasis. Describing a room’s wallpaper sets up a parallel narrative, an allegory, a pause, a color, even an alternative way of being. It’s anti-narrative: the plot isn’t advanced but something is described.

Maybe by spotlighting wallpaper Lynch and Frost are also hinting at a correspondence between wallpaper and cinema. Both deal with the limitations and problems of reproducing reality in another form. Film historian Kevin L. Ferguson: “From its beginnings, wallpaper was a plagiarizing art, meant to simulate more luxurious wall coverings; this is why the dominotiers called them papiers de tapisserie — these were paper facsimiles of tapestries otherwise available only to a small portion of the population. How much richness is lost when one makes the shift to ersatz paper? How much reality is lost when one makes a film?”

This must be where rooms go when they die.

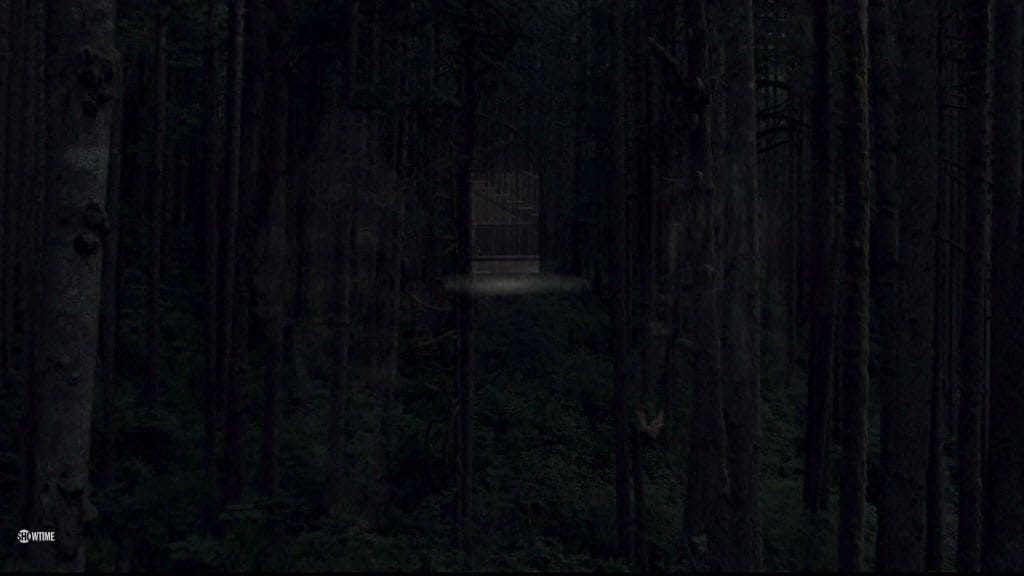

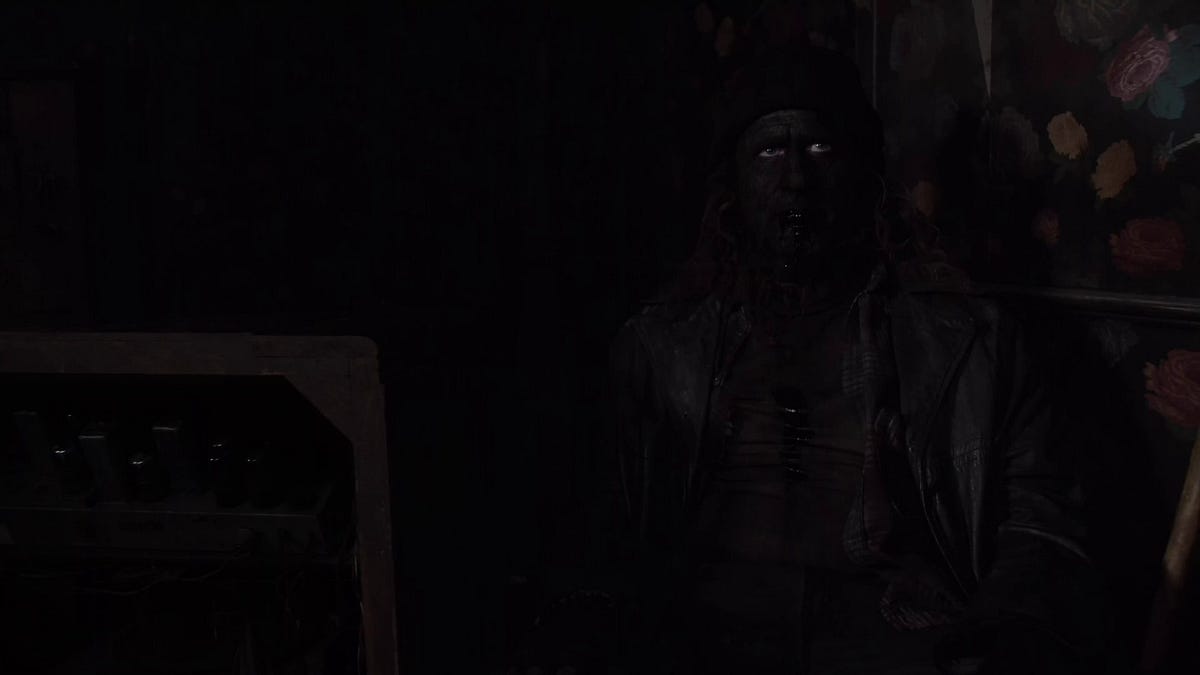

We first see the return of the FWWM wallpaper in Part 11 through the sky gate, and then in Part 15 we get a damn fine look. Cooper’s doppelganger drives to Convenience Store where he meets a Woodsman and those eerie sounds from Part 8. Trinity has also arrived. They walk up the stairs outside the store and then flicker out. No knock, no door.

Suddenly, an image of the forest is superimposed like it’s the dreamer, and we are ushered into the 2nd story room in Doorway Picture, but instead of meeting Mrs. Tremond and her grandson leading us into the Waiting Room, we meet a Woodsman holding the Electrician’s staff, sitting next to the old record player like a DJ Heimdall, opening a gate and leading us to The Dutchman’s.

Mr. C and a Woodsman walk down a dark hallway, and in place of the wallpaper, we see the forest again. A doorway opens like a gate onto a room with more stairs, and at the top, the flowered wallpaper again.

!~?~!

This suggests that on some level it’s all one house–some Victorian nightmare. The 3rd-floor landing opens onto a courtyard, and suddenly we’re outside again, which is fantastically disorienting. The 3rd floor of one world is the ground floor of another.

Shadows from the Walls of Death

Victorian, flowered wallpapers like the ones in Twin Peaks, especially the fancy William Morris wallpapers pouring into the United States from Europe, play a role in the history of poisons. Morris wasn’t concerned at all, and actually co-owned the largest arsenic mining company in the world. He owned lots of mines that extracted raw materials from Indigenous lands for his wallpapers. The US government apparently knew about the dangers and let the papers in anyway, well into the 1890s. When you see old wallpaper like this, beware! It’s full of arsenic-laden settler colonialism.

Children who ate pieces of the wallpaper died. In 1874, one concerned scientist produced a book called Shadows from the Walls of Death to warn consumers, and he did this by collecting and binding together actual samples of the deadly papers and then publishing it. Librarians freaked out. Most of the books were promptly destroyed. Only four were saved and carefully wrapped in plastic.

Each copy also featured Old Testament warnings about plagues and death.

In old American and European houses, the wallpaper paint would flake off and create a thin layer of dust that covered everything. In some cases, the glue on the back of the paper would react with the paints to create a poisonous gas. People got sick. They went crazy. They died with no idea why for ages. Napoleon was killed by his wallpaper.

Did the truth come out in their fictions? Some scholars think that the narrator in The Yellow Wallpaper was really suffering from arsenic poisoning. After all, it was the color and the smell of the paper that drove her mad.

Like FWWM, The Yellow Wallpaper is a story about a woman who is clearly suffering and yet nobody in her life believes her.

The poisonous paint could also be scraped off the wall and mixed with food, and greens were the most lethal. Scheele’s Green. Legends abound of raped and battered women who found liberation and justice through gifts from the wallpaper.

Hiding Time, Hiding Place

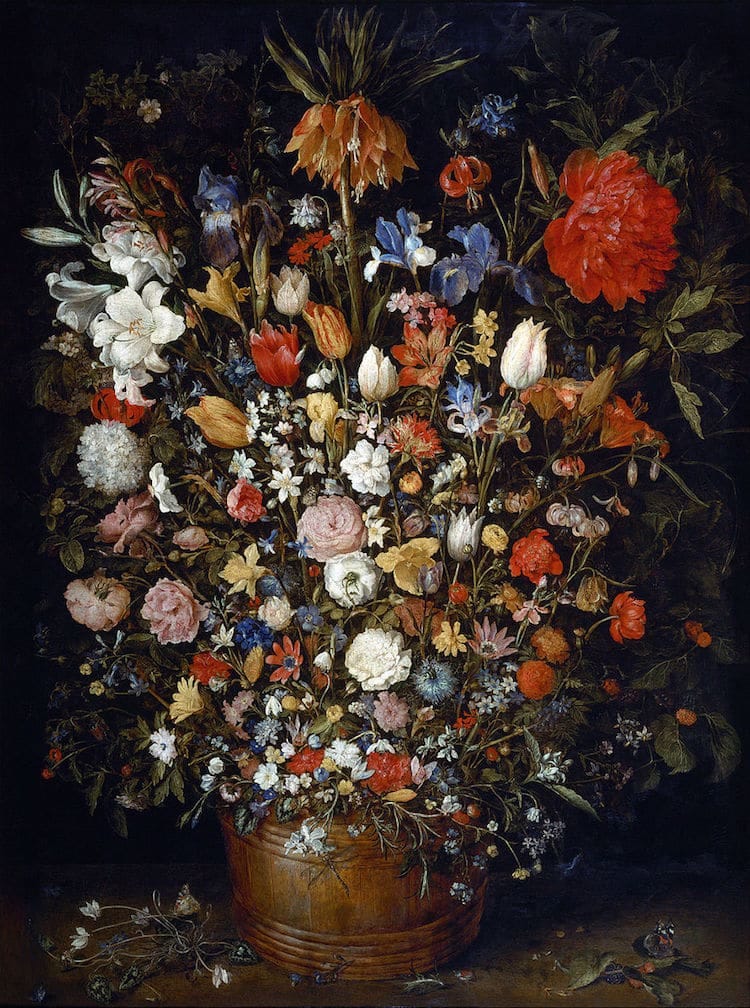

When we zoom in, the wallpaper patterns resemble tiny still-life paintings, memento mori “remember dying” Italian still-life vanity paintings that present flowers and food as emblems of life and death. When we step back, the red and pink splotches are great at hiding stains, while the all-over pattern enchants our cognitive functioning and looks forward to abstract expressionism.

Wallpaper is a complex metaphor, agency, and even parable. Early European wallpapers were literally religious icons . According to Françoise Teynac in his Wallpaper: A history, in France, Christian icons called dominos were placed on walls in lower-class homes where they performed a double function, “being both a talisman against bad luck and a covering for the cracks in the walls.” Double agents… Domino papers were also used in bookbinding and for lining trunks and chests of drawers. “Wallpaper” entered the English language in 1827.

The Visualization of Evil

It’s so familiar. It leads to the Room Above the Convenience Store, to the Palmer house, to the past. It leads to the Waiting Room, to Non-existence, to the Purple Zone, Diane, The Glass Box, and even to the Fireman’s Fortress. All lodge space, hell, all worlds are probably mere wallpapers for the Fireman to swipe through and populate with his thoughts.

Flowered wallpaper made American walls look like British trellises and fancy rose gardens. Of course, forests and real flowers get destroyed to make wallpaper. “We kill with technology and save the victim with art.” Nature was being eliminated by urbanization and bourgeois industrialization so its images were framed and printed onto walls. It’s like Egyptian Nilescapes appearing on the dining room walls of Pompei. Does this reflect “imperialist nostalgia” and other violent colonial coping mechanisms? If so, the flowered wallpaper could signal a destructive presence, but it could also signal a safe space for Laura, a shelter where she can deal with her issues. Are the two really mutually exclusive?

Maybe it’s a friend. After all, Doorway Picture was the only one with her, lying next to her on the manicured lawn, when Laura got her first heart-wrenching glimpse of the man behind the mask.

Did Doorway Picture do something to her vision? We know wallpaper patterns can trigger lost memories, and maybe even lost personalities. Is this Laura’s childhood wallpaper? Is this what triggers her awakening? Mrs. Tremond is like Melchizedek, who appears in time out of nowhere to add a new ingredient to the story. Doorway Picture is the catalytic bread and wine of Twin Peaks.

Temenos

In Unwrapping the Plastic, Franck Boulègue calls the flowered antechamber in Mrs. Tremond’s picture a Jungian temenos or magical enclosure for Laura’s psyche. It’s a dream hideout pocket world where she can feel safe enough to integrate her shadow and disappear. Boulègue brilliantly compares the Red Room to a dark room, “the place where images are developed and reproduced in the red glow of the safe light.” All lodge spaces can be like this, can be Rooms of Requirement.

Some gardens are designed to keep us trapped, while others, secret gardens, accelerate self-realization. They can also be externalized attitudes towards inflamed genitalia. Boulègue cites the use of flowered wallpaper as a hint we should entertain deeper origin stories–expulsions, falls, sexualities, snakes, dirt–and even see Edenic narratives in Twin Peaks. Maybe we should also take another look at The Secret Garden by Frances Hodgson Burnett. After all, that story was so popular in the so-called USA.

A sick family full of secrets heals through the intervention of hidden rooms.

This taps into interior castle territory as we get hints that the universe is even bigger on the inside.

On the other hand, redditor CleganeForHighSepton calls the doorway picture a mirror reflecting the true form of the Palmer house, which they say is evil. “When Laura finally sees herself in it, both the Laura in the picture and the Laura in the Palmer house are in the same pose — with their hand on the door as they look into the room from the threshold…like the Arm’s warning to BOB that “the chrome reflects our image” (e.g. that lodge beings can be seen in mirrors), it’s like the painting is reflecting the “true form” of the Palmer house — as a place of evil, a conduit for Lodge beings, and quite possibly as the ‘physical’ location of the Black Lodge itself.”

How do you know what she likes?

Recentering incest, redditor Illumurian posits that the Palmer House is the Convenience Store, “because that’s what it actually was, for Leland, for BOB. Terribly convenient indeed…”

There is an argument that the meeting above the convenience store (and the planning of Laura’s murder) could be the way Laura felt about the dinner scenes at her house. (In this case, Phillip Jefferies momentarily saw into Laura’s mind). I like the idea that we may be seeing the events of the Palmer House, and by extension, the United States, through the mythopoeic lens of an artist’s imagination recognizing archetypal patterns. The show may even be a spyglass into the world behind this one, the world of aliens, angels, and parasites that cohabitate with us, real and imagined. If you could see into the rooms behind the rooms, the stories behind the stories, the people behind the people, you might see angels, “entities,” intelligences that live one world next to ours.

The Interior Castle

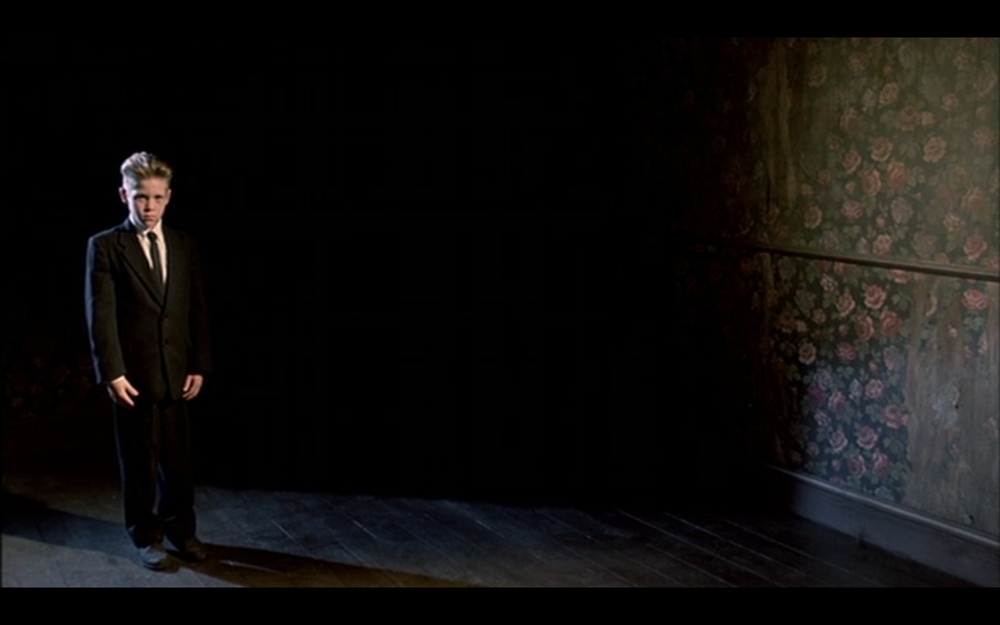

In his brilliant quest to Find Laura, Lou Ming links the rooms of the Black Lodge to the rooms of the Palmer House, and the lodge entities to their human counterparts, or as redditor strandedbaby puts it, “the supernatural ‘players’ and their human ‘pieces'”. Sarah Palmer corresponds to Jumping Man (more-or-less confirmed in s3p15. Ming thinks Jumping Man’s nose is a dream-transfigured cigarette); Laura (or disassociated Laura) corresponds to the Man from Another Place (aka the Arm, BOB’s new partner, and also Laura’s “cousin,” who is actually Maddie/Laura); and Leland corresponds to BOB. Notice how in their Black Lodge versions, Sarah and Laura wear the same red suits.

For Ming, finding Laura is also about finding her complex motivations, and thus the other characters in the convenience store — the Electrician, the Woodsmen, and the Tremonds – shine lights onto fractured and dissociated parts of Laura’s own psyche. For example, Mrs. Tremond is an archetypal grandmother replacing Laura’s own jumpy mother, who is off smoking and screaming. The grandson is Leland as a child.

Sarah

Interior decorators will sometimes match the wallpaper to the woman’s wardrobe. Inside the Palmer house, Sarah’s pink and purple robes match the petals that surround her and further link her to Jumping Man and The Arm. Like a deity, Sarah is wreathed in flowers and flanked by flowers and paintings of flowers. Bouquets hang upside down on the walls. There are flower curtains, flower napkins, flower mirrors, so many flowers but her family is missing. Even her halo in this shot is made of flower-embellished ceramics and crystal dining wear behind glass frames. She surrounds herself with flowers because she’s dead inside. She’s an ashtray. A smoking mask.

Are the dining room and Sarah’s childhood bedroom covered in the same wallpaper?

A signature on a demon’s self-portrait.

The great Steven Miller, in his quest to identify all the props used in Twin Peaks, focuses on these strange, egg-shaped replicas of Italian still-life paintings in the Palmer House. They always come in pairs. These kitschy images seem like such a contrast to the television Sarah likes to watch. But then again, tiny paintings of flowers and fruit were originally intended to be meditations on death, akin to images of animals tearing into other animals.

Wallpaper helps people construct new identities.

All art is a disappearing act. Arbitrary Law (Episode 16) is probably the first time Lynch and Frost show us how easily a storyteller can just wallpaper over a character. In this episode, we also get our first indication that Cooper is Mike. Diane Podcast remarks on how the new Mrs. Tremond in Arbitrary Law is the complete opposite of the previous one as if the Lodge Decorator was saying, “This time, let’s try something completely different in this house.”

“We’re painting the roses red!”

There is a constant issue of failed disguises in Twin Peaks, and in the rest of our lives. Diane Podcast sums it up: “Is the whole thing some ghastly confection designed to hide the truth?”

Perhaps wallpaper helps us think through some of these larger themes in Twin Peaks and elsewhere.

We internalize the external and externalize the internal.

Like avatars or indices, houses and rooms and their wallpaper patterns can represent characters in the show. Sheriff Harry S Truman may be the Palmer’s house in Part 18. No kidding.

Due to some sort of logic of correspondence, people are rooms, and we see this visualized in Part 17 when Diane (or whoever it is) emerges out of and embodying the Waiting Room. She may also be a black, white, and red dictaphone.

In Seasons 1 and 2, Diane was an opening or space into which Cooper could work out his fantasies. Diane podcast’s episode on Diane describes her as “The Invisible Woman,” created in absentia, appearing only as negative space. She is also described as “The Frame.”

Perhaps making up for lost time, in season 3 Diane appears a rotting placenta tulpa orb, a scarred and blinded Asian woman named Naido, a copy of herself, the Waiting Room, and a newly liberated mystery woman named Linda. Listen to John Thorne’s analysis of the many faces of Diane.

John Bernardy, in his impressive exegesis Navigating Between Worlds notes that the Purple Room is also associated with Naido/Diane and American Girl/Ronette “themselves possibly in-between states of Laura and Diane while their tulpas exist nearest the time stream, or under some form of Lodge-style witness protection.”

Both Diane and Laura were sexually abused, and I find it interesting that another main character who gets an astral therapy room after being raped by Cooper is Audrey Horne. Her temenos is filled with books and papers, and it leads to a Roadhouse Room, a White Room, and a Mirror.

Bewitching

Wallpaper is also a trickster, guilty of little white lies (like visually altering the proportions of a room), to helping humans cover up aging walls, to defamiliarizing nature as rococo opulence and/or bureaucratic kitsch (see Gordon Cole’s wallpaper at the beginning of Fire Walk With Me). It wears many hats.

Wallpaper causes us to see patterns and to free-associate. It also sets the scene and communicates a changing mood better and faster than any person can. Aldus Huxley points this out about western art history and drapery in The Doors of Perception.

Like drapery, wallpaper is a “living hieroglyph,” an opportunity for abstraction, and a projection of settler dreams that express, as William Irwin Thompson might put it, a turn on the spiral of history where the pre-industrial symbols (flowers, rock art) and the post-industrial “meta-industrial” symbols (pop art/grids/polka dots) have a certain structural similarity.

It’s interesting that wallpaper patterns may originally come from our environment, but, as Native American artist Joe Feddersen puts it, these patterns also work the viewer into a “zone”…”where signs tenuously dissolve into a modernist aesthetic.”

Wallpaper patterns work us into a zone.

There’s no place like home.

Wallpapers lead us deeper into Laura’s history and into our own. Brenda Greysmith points out that wallpapers give important insight into history because they repeat, reflect, and reinforce a culture’s “idle fancies.”

When we zoom out and look at wallpaper as a ritual, we can appreciate an overall pattern of conquest, a recapitulation of ‘man conquering nature,’ a continual process of miniaturizing, domesticating, and covering up. We see artifice and imperialist nostalgia, but we also see installation art. The history of decorating walls reaches back into the caves. Maybe the most important place it leads is to an armchair in the corner of a waiting room next to a television where Laura Palmer can finally sit down, laugh, cry, and be released from her life.

Conclusion

The flowered paper in Doorway Picture is linked to a hidden temenos and wallpapered antechamber inside each one of us. It signals the mediatic environment inside Laura Palmer—a golden oversoul encircling the planet—and reminds us of our own participation in every story.

Aliens will peak in on us and see how we turn our interiors into hallucinatory funhouses full of garden imagery as a coping mechanism for the loss of innocence and the destruction of nature.

It’s art. Interestingly, David Lynch’s prints are in Wallpaper Magazine. Fractured and kaleidoscopic wallpaper patterns contain histories of women, settler colonialism, racism, rape, ghosts, convenience, motel rooms, atomic Americana, arsenic, lies, secrets, and more. Are there other subtexts we should think about when considering wallpaper patterns and Twin Peaks? What else was happening in the world when this specific, gaudy late 19th-century rococo flowery crap was invented? I889 is the year the Curries unleashed radioactive power leading to the atom bomb. The very first motion picture was filmed in 1888, The Garden Scene. That same year, Scottish scientists learned how to trap neon gas like a genie in a lamp, and those lights would soon usher us deeper into Twin Peaks and deeper into the dark night.

One of the best essays on Twin Peaks that I’ve read! Wall to wall erudition.

Thanks for the interesting read! Very well researched.