Twin Peaks and much of David Lynch’s narrative and artistic practice is shrouded in mystery. His work calls out to the audience to make sense of what has been encountered yet he tells us there is no one correct way of making sense of his films. They are mysteries, hidden within secrets, with key pieces of narrative information left out to spark speculation and imagination. This has resulted in a plethora of possible readings, tracking, spiritual paths through eastern religion, Gnostic thinking, hermetic and occultic ritual, conspiracy theory, quantum physics, modernism, post modernism, art theory, psychology, gender studies, materialism and so on.

In this series of articles, I will add my voice to the conversation and suggest, not altogether originally, that finding the definitive answers is not the point. Twin Peaks, like much of Lynch’s work is about the process of making sense of being in the world, which is by its very nature ongoing. To that end, I will make the case that Twin Peaks, like Lynch’s broader practice, exists in an absurd space, defined by this notion of ongoing sense making, amidst an existence that does by definition not make sense.

The Oxford Dictionary online tells us that ‘absurd’ is an adjective that denotes “wildly unreasonable, illogical or inappropriate” events or behaviours, and as a noun indicates “an absurd state of affairs.”[1] All of these qualities can be applied to Lynch’s moving image work, however one cannot escape the feeling that his work is far from illogical and that there is intent within the madness. As such it is more useful to look at Lynch’s work through the prism of absurdism which expands the above definition by adding that absurdism is “the belief that human beings exist in a purposeless, chaotic universe”.[2] Absurdism is therefore a philosophical way of looking at the world, and of being aware of being, that tries to define and make sense of this reality.

How then can Lynch’s work be viewed as absurdist? While a clear case can be made that Lynch does not believe existence is pointless, an equally strong case can be argued that he does believe the exact nature of being is not evident to us in this reality. It can also be argued that Lynch employs the absurd, like he utilises expressionism and the uncanny in his work to encourage the audience to question the meanings they communicate , and in turn to examine their own experience of being in the world. To explore this idea I will briefly discuss the philosophy of absurdity, and then its expression in the arts, identifying how these ideas are used in Lynch’s work.

The Philosophy

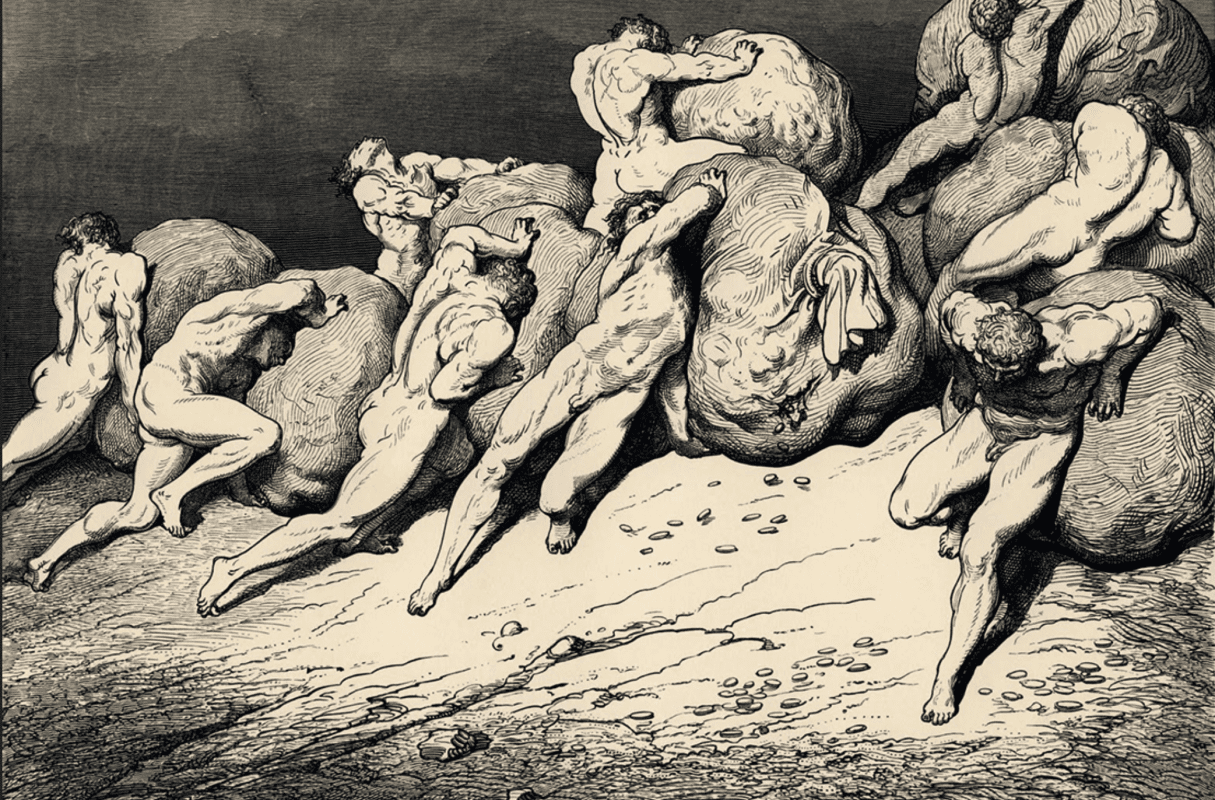

Absurdism is a school of philosophy, often associated with existentialism, that argues existence is in and of itself meaningless. In Albert Camus’s 1942 work, The Myth of Sisyphus he uses the Greek myth, of the same name, to illustrate the nature of absurdity. In this myth Sisyphus is punished by the Gods for refusing to die. (Interestingly in the various versions of this myth, Sisyphus tricks, Thanatos, Hades and Persephone to escape death – a theme relevant to The Return, and Cooper leading Laura away from her death, not to be explored in this article). When captured by the gods, Sisyphus is punished for his hubris, sentenced to repetitively carry a rock to the summit of a mountain time and time again. Each time he is about to reach the summit with his burden, the rock rolls back to the base of the mountain and Sisyphus begins his task anew. Through this metaphor Camus argued that life is mirrored and its futility, in the face of a chaotic and indifferent existence, laid bare. Camus does not however tell us the universe is absurd in and of itself but that… “what is absurd is the confrontation of the irrational and the wild longing for clarity, [certainty and meaning] whose call echoes in the human heart”. [3] Absurdity therefore resides in the void between our “longing for clarity” and the indifferent silence of the universe, and in our conscious relationship with the world. [4] This idea, I believe, expresses perfectly the viewers relationship with Twin Peaks. In watching The Return, we sought answers and resolution, but this is not what we were given. We were instead given what we needed and not what we wanted. We did not revisit the world of Twin Peaks as we remembered it but a changed place, an idea I will explore in follow up articles. We did not see all the characters we wanted to, and those we did , bar a few, were not leading the lives we hoped they would. This, in a very simple way, exemplifies Camus’s own fictional exploration of the absurd and presents to us a world in which, time, ambition, love and life are changed in a moment by arbitrary events and choices. The Twin Peaks universe however, unlike Camus’s, does not however remain silent when interrogated, it instead speaks to us using oblique, ambiguous and illogical words that we will forever be trying to make sense of.

While Lynch’s obfuscation may frustrate, enliven and entertain, Camus argues the realisation and confrontation with absurdity “compels profound anxiety, anxiety so unbearable that it commonly elicits a longing for death”[5], or the creation of self-consoling delusions and false narratives into which their creators posit meaning and retreat into a state of “bad faith” or “philosophical suicide”.[6] These delusional narratives are evident in Lost Highway and in Mullholland Drive. In Lost Highway, Fred, unwilling to acknowledge murdering his wife, escapes execution by literally becoming someone else. In Mullholland Drive, Diane likewise escapes into a fantasy, as Betty, to elude her failed career, love, and the murder of Camilla, the object of her desire. Yet in both cases reality intrudes, collapsing fantasy, resulting in Diane’s suicide and Fred’s continued attempts to flee what he has done in his Möbius strip reality.

In many ways these film perfectly explore an absurdist reality and perspective, however Lynch then retreats from the absurd and allows his characters to transcend their horror and escape once more. This occurs when Diane commits suicide in a moment of existential horror and despair but is then reunited with Camilla in death in an act of what Camus would define as philosophical suicide – by acknowledging absurdity then flinches from it, positing hope where nothingness resides.

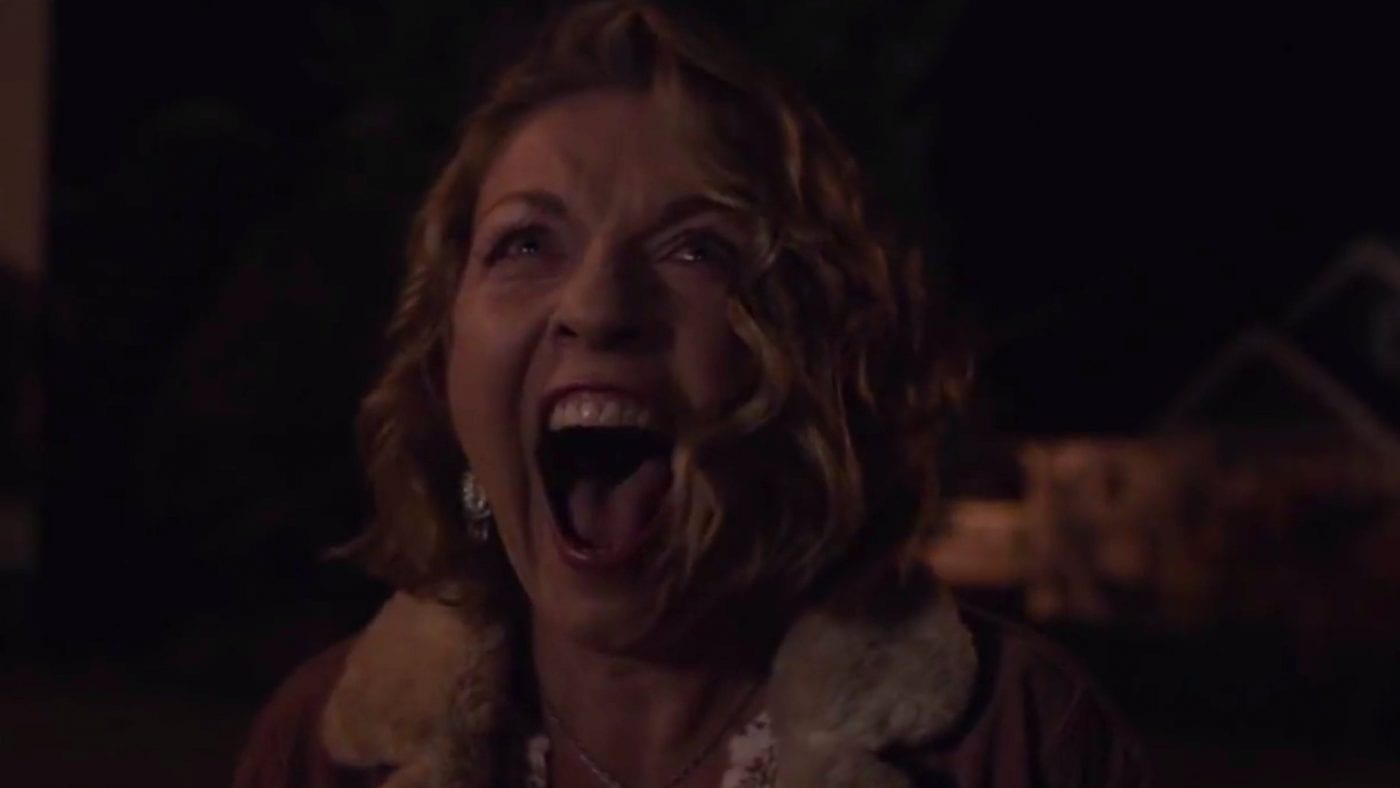

Unlike the films noted above, Twin Peaks has avoided being defined as an absurdist work. Yes, a case can be made for Fire Walk With Me, as a standalone film, being classified as absurd, with Laura seeking out death to escape a nightmare reality. Similarly, it is possible to argue that Twin Peaks utilised absurdist techniques in its storytelling tool box (to be discussed below). Nevertheless, the mysticism and transcendentalism present in the series made the absurd title difficult to attach. The Return, however, has changed this. Yes, Margaret’s log becomes gold as she dies, Ed and Norma find happiness, BOB is bashed to pieces, and Cooper’s tulpa goes home to Janey-E and Sonny Jim. Yet at the same time, Lynch gives us a deeply damaged Audrey, trapped within herself, Steven’s suicide, the negation of Diane, and a return for Carrie and Copper that culminates in an existential scream of crisis and confusion. In this moment, unlike in Mullholland Drive, the trauma and abuse Laura and Carrie suffered is not magically undone but is instead manifested anew, demanding to be acknowledged and navigated. In this moment Cooper is found wanting, and fails in his attempt to save Laura. To make matters worse death no longer takes the sting out of life, by negating absurdity. Instead, Lynch and Frost have set in motion a Sisyphean cycle of not saving and saving Laura. For her, there is now no angelic deliverance or negation through death. Instead, she must carry her trauma, her rock, with her for all eternity to acknowledge what she has eluded, as Carrie by forgetting and as Laura by seeking death. In this new cycle Laura also becomes Cooper’s “rock,” his “thing,”[7] that he must struggle with for all eternity, seeking to save her but failing, time and time again.

While this may seem bleak, I would suggest it is not. What Lynch and Frost have done is to allow Cooper and Laura to acknowledge and know the condition in which their existence is framed. Camus suggests we should live with our eyes open to the absurd, rebelling against hope of divine salvation and the inclination to seek out unity where none exists. For Camus, suffering makes us aware of absurdity and allows us to be more fully in the world and own our existence. I can see that both Lynch and Frost may be suggesting that Enlightenment, Brahmana or Transcendence is achieved across many lives, and that our heroes are only so far along that path. Yet it seems to me that Laura and Cooper now exist within an eternal loop similar to that conceived by Friedrich Nietzsche. This concept, discussed in the Gays Science and in Thus Spake Zarathustra imagines an eternal loop of recurrence in which all life’s experience and choices are re-experienced again and again.[8] For Nietzsche this was not to be viewed as torment of regret or guilt but instead as a life embraced, acknowledged and accepted for what it is.

Søren Kierkegaard, another philosopher who explored the absurd, thought the idea of a cosmos bereft of “eternal consciousness,” as posited by Nietzsche and Camus was “empty and devoid of comfort”.[9] He instead reconciled himself to the absurd through a “leap of faith,” positing divinity where none could be detected. In doing so, he argued belief in an absurd, God was preferable to an existence of divine absence.[10] In constructing his argument, Kierkegaard used the story of Abraham taking his son Isaac to sacrifice to God. In this journey, he argues Abraham becomes a Knight of Faith by submitting to God’s will and by giving up all that he loves before God to prove his faith. In attaining this position, Abraham and Søren both trust in God that their lives are with purpose even though they may never know what that purpose is. In some ways this idea is also evident in the Return with both Laura and Cooper putting aside all they love to achieve salvation. Cooper puts aside his Dougie life with Janey-E and Sonny Jim, and then his own life in the world as Cooper, becoming Richard to undo the wrong done to Laura and to save the world. Similarly Laura escapes her own death and sacrifice by taking a leap of faith, trusting in Cooper, but is instead delivered into a wanting world as Carrie, in which her life may not be much better than it was before.

While Kierkegaard’s ideas are present in Twin Peaks, Camus seems to have the final word through his retort to Kierkegaard that “seeking what is true is not seeking what is desirable.” For Camus the absurd mind would seek out truth, no matter how unpalatable, and in so doing be able to make life one’s own.[11] This is what both Lynch and Frost have done, despite Lynch’s own discussions about unity and transcendence, Laura nor Cooper have transcended the conditions of their existence. If anything, they have only transcended their own blinkered understanding of their circumstances. Yet perhaps this is enough?

At the end of Part 18, Laura whispers into Dale’s ear, as she has done before, in what appears to me to be a moment of affirmation for her, and realisation for him. In this moment, they in some ways become like Sisyphus’ journey down the mountain, perhaps smiling. They have made their lives their own, ready to climb the mountain peak again, knowing they and not the gods are the masters of their fate.

The Theatricalisation of the Absurd

How else then does Lynch explore absurdist themes in his work? Camus again offers the next clue in his essay on Kafka’s texts. Like Lynch, Camus admires Kafka, praising his texts for their absurd quality in their “absence of ending,” “suggested explanations … not revealed in clear language” and Kafka’s portrayal of the “extraordinary” in the most natural of ways.[12] When discussing Metamorphoses, Camus is particularly taken by the way in which the main character, Samsa, reacts to his transformation into an insect, in being more concerned with not getting to work on time, rather than with his transformation.[13]

This “absence of ending,” “suggested explanations … not revealed in clear language” can be found in many of The Return’s non-sequitur sequences, Steven and Becky’s story, in Audrey’s narrative arc, and even in the series final sequence. The Glass Box sequence in New York and its related investigation are a good example of this. Not only is the glass box never explained, no explanation is given as to how or why Tracey and Sam were killed, if it was intended or accidental, and to what end. We can assume that the experiment, Mother and Judy, are the same creature, but we are never told this is so, nor whether what we saw in the glass box is actually that creature. In Episode 4 we see Cole, Albert and Tammy discuss the deaths of Tracey and Sam and learn that an investigation is underway. Yet this narrative strand, like so many others, is never pursued to fruition. The only new information we glean is to learn Mr. C was involved with the project in some way, but how is again left to our imagination. At the beginning of this meeting, we observe these tropes again in the briefing on the “Congressman’s Dilemma” in which we are presented with a series of absurd clues left by the suspect Congressman in his own garden. This case, along with Sam and Tracey’s murder investigation, is never mentioned again. Likewise, at the end of this sequence in Cole’s office, we are confronted with a photographic portrait of Kafka sitting alongside a landscape of the trinity nuclear test explosion. Here Lynch is not only signalling that he deems the creation of nuclear weapons absurd but also that the unfolding narrative of The Return will unfold under the watchful eye of Franz Kafka. If this symbolism were not clear enough, Albert dryly and pointedly observes…

“The absurd mystery of the strange forces of existence”.

While The Return points to Kafka’s influence, it also draws on the Theatre of the Absurd and the plays of Beckett, Ionesco, and Genet, their theatricalisation of the existential. While these writers and others did not see themselves as part of a movement, they nonetheless exhibited similar attributes in their portrayal of a world without meaning or purpose. In these works, the audiences are often confronted with non-linear and circular narratives, with the blurring of time, place, and identity, confused or absent character motivation, ill-defined menace, anxiety, bawdy humour, and illogical and clichéd dialogue[14]-traits that are immediately recognisable in Lynch’s work.

While these tropes are regularly used by Lynch in his narratives, they often remain unacknowledged, explained away as surreal, or noted because of the Lynchian quality of the performance and drama. The only time the absurd is however discussed in regards to Lynch and Twin Peaks is in relation to humour. A good example of this can be found in Part 1, when Marjorie Green calls the police after detecting an unpleasant odour coming from Ruth Davenport’s apartment. When the police arrive, they become caught up in a humours and nonsensical conversation with Marjorie about gaining access to Ruth’s apartment. In this sequence, we not only explore the absurd through humour but also through the use of confused language, identity and motivation as well as circular narrative. Initially Marjorie has to be prompted to remember she called the police, then after some initial confusion over police codes and Ruth’s room number, the officers go to find the key. The key, it seems, is in the possession of Barney’s friend Hank, who gets angry at Harvey, with whom he is talking to on the phone, wanting to be cut in on a deal he knew nothing about, and for calling the police, who are only interested in finding the key to Ruth’s apartment. Finally, Marjorie realises she had the key around her neck the whole time, as she was meant to water Ruth’s plants while she was away, which she forgot to do.

While this sequence and others like it are amusing, the focus of critics on humour only serves to distract from broader absurdist concerns. These concerns are explicitly explored in Part 15 when Steven Burnett, Becky’s husband, and Gersten Hayward hide out in the woods, drug-fucked, confused, and contemplating a horrifying act of self-violence. A marker of absurdity in this scene, like the Marjorie Green scene, can be found in the use of language. The incoherent phrases, words and sentences that babble out of Steven’s mouth, not for the first time, point directly to the failure of language to communicate meaning.[15] This has been evident in Steven’s entire arc, evidenced in his poorly worded resume, in the lies he tells to Becky, and in the incoherent violent rages he inflicts on her. This degradation of language, however, signals Steven’s isolation, desperation and self-destructive inclinations.

This confusion is compounded further by Steven’s incoherent diction making it almost impossible to understand the very words he speaks, let alone grasp at their meaning. This is a key technique employed by playwrights like Beckett and Ionesco who repeatedly illustrate human inability to communicate either because the tool of language is blunt and imperfect, or because those who speak simply have nothing to say. This failure of language is further illustrated by the fact we do not know what terrible act Steven has committed, or if he has done what he thinks he has. It is implied he may have killed Becky, but the audience knows that Becky was going to the Double R to have pie and ice-cream with her mother. If this is where Becky is, Stephen’s rising dread is the by-product of an addled brain and evidence of a body that cannot recognise its own reality, let alone make sense of the external world. If, however, Becky has been murdered, Shelley’s claim that ice cream and pie make everything all right has been proven wrong. In both cases absurdity is made manifest.

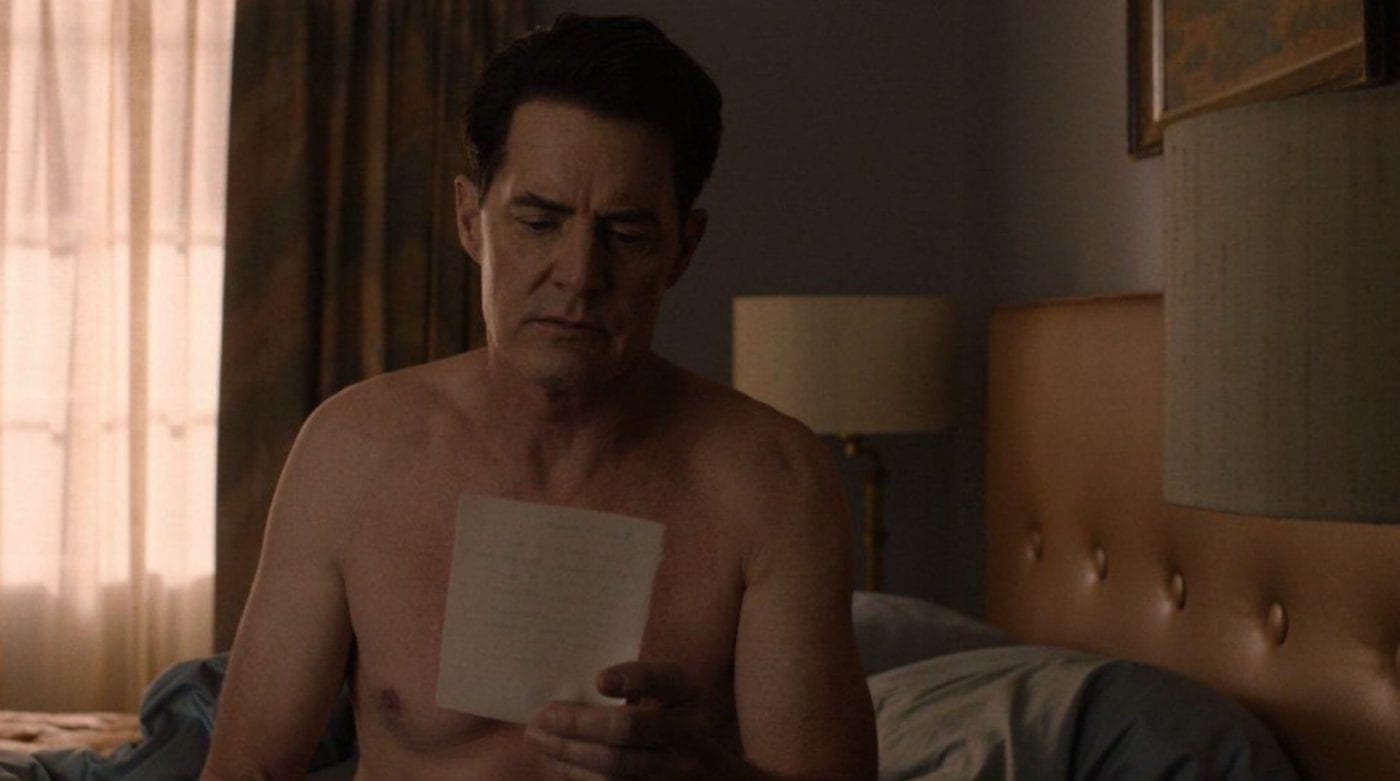

This slipperiness not only creates confusion but also gives rise to a sense of menace and formless dread that pervades the work, another key absurdist device used to highlight existential aloneness. When Diane and Cooper cross over from their world through the portal at 430 miles from Twin Peaks into another, we as an audience experience a growing sense of unease. Cooper warns Diane that everything may be different after they go through, but they both go through all the same. In doing so, we assume they seek to undermine the ill-defined menace that is Judy, and to rescue Laura from whatever tore her out of the waiting room. The unease that infects this final part of this journey is compounded when they arrive at another road side hotel and Cooper goes in to book a room. While Diane sits in the car, she sees and is seen by a double of herself, staring back at her from across the motel forecourt. Whether this double is Judy, a doppelgänger, a tulpa, or imagined, we don’t know, and in not knowing, our anxiety rises. This tension is further exacerbated by the following sex scene, a seeming ritualistic acknowledgment and putting off of Diane’s past, its pain, and perhaps more. Even at its most simple, the act we witness shows us two people who we want to connect but know should not. In the intimacy of this embrace Diane and Dale only seem to find sadness, negation and isolation. So in the morning, when Cooper wakes and finds Diane gone, as Linda, and himself as Richard in a different motel with a different car, we are left questioning the nature of the reality in which Cooper finds himself, as well as the authenticity of the world we have invested so much in.

In the following scenes, we the audience are confronted with the full extent of a non-linear and circular narrative, in which the blurring of time, place, and identity, and ill-defined menace and anxiety are brought together. Laura, like Cooper, has become Carrie, but unlike him, she cannot remember who we think she is. What’s more, not only have our characters shifted identity, the space in which their story takes place has as well. Not only is the dramatic world of Twin Peaks authenticity called into question but also the position from which we have watched this spectacle. Here, the humour is gone as we have instead been driven to the edge of understanding. With The Return’s final, devastating and culminating cry, the entirety of Twin Peaks is reframed, shifted into a disorientating existential space in which the possibility of meaning is thrown forever into flux. In doing so, Lynch has made his most complete absurdist work while we as an audience are left grasping for meaning, hoping not to be swallowed up by the darkness.

In my next article I will attempt to explore this absurdist reading of Twin Peaks within a liminal context and to make sense of the what was encountered as Dale found his way from the lodge into Carries world.

Bibliography

“Albert Camus.” Standford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2012, http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2012/entries/camus/.

“Albert Camus.” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2012 Edition), 2012, http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2012/entries/camus/.

Baré, Simon. “This Is Me, My House (Negotiating Meaning Amidst the Betwixt and between of an Absurd Existence).” Master of Fine Arts, University of Syndey, 2016.

Camus, Albert. The Myth of Sisyphus. [Le Mythe de Sisyphe]. Translated by Justine O’Brien. Camberwell, Victoria: Penguin Group (Austrlia), 2005.

“English Oxford Living Dictionaries.” English Oxford Living Dictionaries, Oxford University Press, 2018, https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/absurdism.

Esslin, Martin. “Theatre of the Absurd.” The Hudson Review 67, no. 4 (Winter 2015): 7. https://search-proquest-com.

Kierkegaard, Soren. Fear and Trembling. Translated by Alastair Hannay. Penguin Books – Great Ideas. Collins Street, Melbourne, Victoria: Penguin Group (Australia), 2005, 1843.

McMahon, Jennifer. “City of Bad Dreams: Bad Faith in Mulholland Drive.” In The Phillosophy of David Lynch, edited by William J Devlin and Shai Biderman, 113-36. Lexington, KY: The University Press of Kentucky, 2011.

Shaw, Daniel. “Nietzschean Themes in the Films of Charlie Kaufman.” In The Philosophy of Charlie Kaufman, edited by David LaRocca, 254-68. Lexington, KY: The University Press of Kentucky, 2011.

Singleton, Brian. “Theatre of the Absurd.” In The Oxford Companion to Theatre and Performance, edited by Dennis Kennedy. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Notes

[1] “English Oxford Living Dictionaries,” English Oxford Living Dictionaries, Oxford University Press, 2018, https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/absurdism.

[2] “English Oxford Living Dictionaries.”

[3] Albert Camus, The Myth of Sisyphus [Le Mythe de Sisyphe], trans. Justine O’Brien (Camberwell, Victoria: Penguin Group (Australia), 2005), 20. Simon Baré, “This is Me, My House (Negotiating meaning amidst the betwixt and between of an absurd existence)” (Master of Fine Arts University of Sydney, 2016), 1.

[4] Camus, The Myth of Sisyphus; Baré, “This is Me, My House (Negotiating meaning amidst the betwixt and between of an absurd existence).”

[5] Camus, The Myth of Sisyphus, 20, 29; Baré, “This is Me, My House (Negotiating meaning amidst the betwixt and between of an absurd existence).”

[6] Baré, “This is Me, My House (Negotiating meaning amidst the betwixt and between of an absurd existence).”

[7] Camus, The Myth of Sisyphus, 118-19; Baré, “This is Me, My House (Negotiating meaning amidst the betwixt and between of an absurd existence),” 7.

[8] Daniel Shaw, “Nietzschean Themes in the Films of Charlie Kaufman,” in The Philosophy of Charlie Kaufman, ed. David LaRocca (Lexington, KY: The University Press of Kentucky, 2011).

[9] Soren Kierkegaard, Fear and Trembling, trans. Alastair Hannay, Penguin Books – Great Ideas, (Collins Street, Melbourne, Victoria: Penguin Group (Australia), 2005, 1843), 14; Baré, “This is Me, My House (Negotiating meaning amidst the betwixt and between of an absurd existence),” 8.

[10] Camus, The Myth of Sisyphus, 39. Baré, “This is Me, My House (Negotiating meaning amidst the betwixt and between of an absurd existence),” 9.

[11] Camus, The Myth of Sisyphus, 39. Baré, “This is Me, My House (Negotiating meaning amidst the betwixt and between of an absurd existence),” 9.

[12] Camus, The Myth of Sisyphus, 121, 24; Baré, “This is Me, My House (Negotiating meaning amidst the betwixt and between of an absurd existence),” 10.

[13] Camus, The Myth of Sisyphus, 121, 24; Baré, “This is Me, My House (Negotiating meaning amidst the betwixt and between of an absurd existence),” 10.

[14] Brian Singleton, “Theatre of the Absurd,” in The Oxford Companion to Theatre and Performance, ed. Dennis Kennedy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010).

[15] Martin Esslin, “Theatre of the Absurd,” The Hudson Review 67, no. 4 (Winter 2015), https://search-proquest-com.