Lynch on Lynch was like a bible to me for many a year. At a time when the internet was just raring to go, but interviews were in short supply, I was grasping at any news clippings or snippets of Lynch-like goodness. To get a book from an interviewer/editor who really knew his subject, and that was crammed with revelatory personal details, anecdotes and what’s more—actual ANSWERS from David Lynch—Holy Jumping George we had a winner!

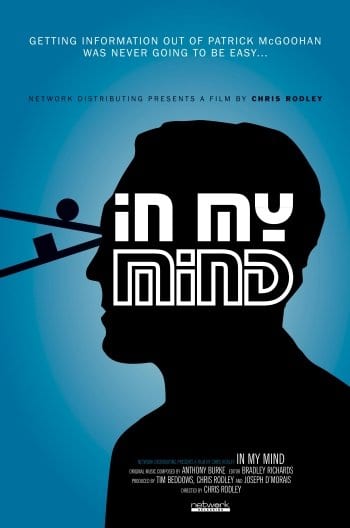

Chris Rodley is a man of many talents. If anyone has checked out his documentary on The Prisoner (featuring the man behind that revolutionary TV show, Patrick McGoohan), you would know that Chris is a witty, down-to-earth chap who has been out interviewing many a filmmaker, actor (and more) for quite a few years.

The opportunity to spend over 100 minutes talking to someone I had the utmost admiration for was immensely intimidating and ultimately satisfying in a way I hadn’t expected. Chris was open to any questions and incredibly honest with his views. I could have talked to him all night (and he would probably say it would be difficult to stop him from doing so!).

Anyway, less preamble—let’s get to the interview…

PB: You’ve written books on David Cronenberg and David Lynch, and I think you cornered the market a little bit on Lynch…

CR: Yeah, I think a certain kind of market maybe…

PB: Your book Lynch on Lynch was like my bible for the longest time. Before that, I had to get snippets from magazine articles and the like. In those, he always seemed so private in terms of revealing anything and you got so much from him! Before your book, he seemed to say very similar things to different people…

CR: Yeah. But most everyone does though. After 35 years interviewing all kinds of people my heart sinks when they say “Well, it’s like I say..”. No, don’t tell me something you’ve been saying for years, tell me something different! But it’s understandable. If you think you have come up with a good idea, or a good metaphor or something, then they can be regurgitated!

I don’t think David Cronenberg did it a lot. He was always kind of thinking, a sort of constant evolution in his case. I don’t think he was ever intellectually lazy. He tended not to repeat himself.

PB: I guess it depends on how successful you are, and how many interviews you have to do. It’s only natural you are going to end up re-treading certain ground.

CR: Yeah. You know, David Lynch doesn’t like doing it [interviews]. And so it’s always really, really difficult for him. So whatever makes it easier. It’s knowing how to work with individuals—you can’t apply the same things to everyone. You need to find a way around people’s fears! Fear of saying too much, giving too much away, fear of destroying the magic. It’s funny, with Lynch the constant thing about the baby in Eraserhead—there are probably five people in the world who know how it was done because they were working on the film. It’s fine by me that he doesn’t want to talk about that. I know it’s irritating to some people, but it’s fine because it will probably be some very banal answer. It’ll be an answer that will just take everything away from it.

PB: I’m a big believer in not wanting to know how the baby was made.

CR: Well Lynch would say “don’t do that,” because it reduces it down and makes it less magic… But Kubrick once explained the ending of 2001 to someone who simply called him up and asked him (I don’t really do YouTube, but it’s on there)—and Kubrick tells him everything! What Kubrick does say is pretty much what you would have thought so no big surprises, but there are these little details, tiny little details which are things you would never have thought of. I thought by him talking it through and describing what it meant to him and what was on his mind, it actually made it bigger. It didn’t reduce it actually, it added to it. I’ve been tempted to email Lynch and say you know what, you keep saying it’s going to spoil things if you explain them a little, but look at this and see—it doesn’t spoil it. It actually makes it better. It’s okay occasionally to say what’s on your mind, what you’re thinking of. It doesn’t take all the magic out of stuff. But it’s okay though, Lynch won’t talk about stuff—it’s frustrating for a lot of people but it doesn’t matter too much. It might matter when you get to Twin Peaks: The Return, because you’ve got to unpack so much that you do actually, I think, need some help!

(both laugh)

CR: I didn’t know about Tulpas, I didn’t know all this stuff and I think if there’s stuff getting in the way of me being able to enjoy it fully then I’d appreciate some help frankly.

PB: Did you read Mark Frost’s two books?

CR: I read the first one. I didn’t get the second one and I don’t know why. I got the feeling that David and Mark were working on completely different parallel lines with not much crossover. I’m not sure how much they would help me. I think in terms of Twin Peaks, David Lynch is really primarily interested in Laura Palmer and the whole series was about bringing her back to life in a peculiar kind of way. Whereas I think Mark Frost is interested in pretty much everybody, all those characters. Lynch has a deep, deep fascination with that dead girl, make of that what you will, it doesn’t matter. I didn’t get the second Frost book because I wasn’t sure how much it was going to add to it.

The first was pre-the series, the whole backstory of the town with lots of interesting things. But something that comes out after you’ve seen the series, or near to the end of the series, you’re sort of off on your own thing—so I didn’t read it.

I don’t know how they work out their relationship. It’s an interesting thing. [Frost] comes from an extremely kind of straightforward narrative television. Thinking about it, I don’t know how they got mixed up together in the first place.

PB: I think it was something to do with their agent, a suggestion that they work together. I get what you mean, they are from different worlds and Twin Peaks ended up being this beautiful marriage of those two worlds and then, as you said with season 3, it’s a little bit disconcerting for fans to know that Mark wrote the books on his own, and Lynch directed the series on his own. But at least they worked together on the scripts. Apparently anything Lynch then added to the show, he ran by Mark, and Mark apparently never said no to anything. They both seem to have their own particular view on the world of Twin Peaks, on what’s important to them? Mark may be more expansive, the metaphors. Lynch about Laura Palmer, the broken beauty—it’s a complicated relationship to me.

CR: Yeah. When Lynch was about to walk away from The Return because of the budgetary problems I just thought that was never going to happen. Then we got those cast members saying that Twin Peaks without David Lynch is like a doughnut without a hole and all that kind of stuff. I assume when he was walking away he knew that was never going to happen. A lesson from that series seems to be an issue of control. You know, the end of Inland Empire seemed to be a very purposeful farewell for me, where you get a lot of people in a hotel foyer in Poland—they all sing and they all wave goodbye—that’s you (Lynch) saying “I’m not going to have anything to do with this world anymore”. That last series [The Return] is like, “if I’m going to do this I really do have to lock it down”.

He’s been involved in a lot of things where he’s had 100% control over them and he doesn’t want to surrender that, like he’s had to in the past. “If I can just paint or do great things like Dumbland—all those things I’m doing that are 100% me. I don’t have to justify them to anybody or have some asshole from TV looking at my rushes”.

I appreciate what was going on, it was really about a lockdown. I think there are some problems with lockdown though (laughs). With Inland Empire I was just begging for an editor!

PB: Well, there was a whole hour and a half of the film, ‘other things that happened’, that was released on the DVD as an extra.

CR: Sometimes [this is] good. I ran an independent cinema for a while and ran some director’s cuts and they were always worse! I think maybe the director’s cut of Heaven’s Gate made sense to me, where the proper length of the film was better than the two and a half hour version. I think only Ridley Scott, his recut of Alien, was shorter! Same as Cronenberg—cut, cut, cut to the bone. I always really admired that about him—don’t indulge yourself.

PB: You are a director of many films and documentaries, and you’ve won awards. Was that a common ground for you when you started working with Lynch? And you have a background in painting as well—I know you’ve stopped painting and Lynch chastised you for it!

CR: He could not understand why I’d given it up! Because for him, it is the thing, it’s where it all begins and ends. He made me feel guilty about it. But yes, it might have helped that some of the things that he was interested in, I was interested in too. We had some things in common.

I saw his show at Foundation Cartier [The Air is on Fire exhibition in Paris in 2007]. I think that occasionally in the past Lynch has felt uneasy about being a filmmaker who also paints, and played it down for years because he doesn’t want to be seen as a director who paints in his spare time because he doesn’t, he takes it very seriously. The show was gobsmacking. I wondered if it was because I was biased but I don’t think it was. I couldn’t believe the amount of imagination and amount of work, that this person—it just comes out. The paintings, the music. The sheer force of creativity is gobsmacking. It’s a constant flow of stuff. It’s not fair to be good at so many things! (both laugh)

PB: How did you get into documentary making?

CR: Firstly I had a sniff of redundancy coming when I was programming the ICA Cinema in London in the early ’80s (laughs). I had a moment on a train platform at Finsbury Park—just what am I going to do? And I had written a couple of articles about The Prisoner—and on the opposite side of the platform I saw that Channel 4 were about to rerun the series.

I went to Paris to try to get the rights to open a film for the ICA, and while I was there I went to a little bar, and I started writing what I guess was a treatment, for a documentary—which was something I had never done. I started writing a thing about a documentary that might go out at the end of the run of The Prisoner—5 pages. Channel 4 had only been running for barely a year and they called up and said: “come in”. They said “we are going to make this, but you don’t know anything about making documentaries for television do you? And I said “No I don’t” and they said, “well, you don’t have to worry”. It was so casual in those days! Imagine that now! I mean literally, I knew nothing!

PB: Yeah you would end up trying to do your own thing on YouTube or something.

CR: Yeah, and they said, “you don’t know anything so we will stick you with a director and a producer—let’s go”. Within a couple of weeks, we were in Los Angeles—and you’ve seen the documentary and you know how that turned out! It was awful—I thought that was the end of my new career.

PB: Well Patrick McGoohan is a tough nut to crack for your first documentary!

CR: Yeah! When I got back the director of the ICA asked, “did you enjoy that—with Patrick McGoohan and Los Angeles and all that?”. Which was his way of kind of telling me I was about to collect my redundancy pay.

CR: Yeah! When I got back the director of the ICA asked, “did you enjoy that—with Patrick McGoohan and Los Angeles and all that?”. Which was his way of kind of telling me I was about to collect my redundancy pay.

In those days, Channel 4 had a remit to make innovative television and get 10% of the audience share—which I thought, well those two things don’t really go together but anyway (both laugh). So it was all just easy [to begin working with them again]. And because I had gotten to know Dennis Hopper really well, because I had distributed his film The Last Movie (the only person ever to have distributed that, still); so I wrote a treatment for a film about Dennis, sent that in and they said “yes, we’re gonna make this” and that’s how it went! In those days if you could deliver the subject, the talent, then that was fine. They thought that you could learn how to realize your ideas by putting you together with people who had the experience, and who were sympathetic.

If you had any kind of initiative, any kind of passion, you could go far. For many, many years now, that’s not been possible.

PB: So back then you were making it up as you went along—nowadays, are you more of a director for hire?

CR: I find it more difficult now, plus most of the things I would kill to get made, no one in their right mind would be interested in. Now it’s all big companies, swallowing up all the smaller companies. It’s a completely different landscape. I feel sorry for people trying to get started now.

PB: Some might argue nowadays it’s easier to pick up the technology and do something.

CR: Yes it is…

PB: But there’s not the people out there to get traction with—it’s larger conglomerates now. There’s not necessarily anyone out there to buy it—the appetite for it may not be there, or it’s not a big enough product etc.

CR: The TV landscape—we used to be top of the pile, but nowadays we have to look to America for a decent TV series. We may have had The Bodyguard but guess what? He’s going to drive off into the fucking sunset with his wife who has decided she likes him now, with the kids! I was really disappointed with that ending!

PB: You’ve spoiled the ending now! (laughs)

CR: (laughs) Oh sorry!

The final line of The Return “What year is this?” And then it ended with a scream, which is more my kind of thing. I don’t expect to watch something that’s kept me on the edge of my seat for 6 weeks and then see the main character and his estranged wife ride off into the sunset on a family trip! I don’t think that’s being honest to the idea—something David Lynch goes on about a lot.

PB: What TV currently impresses you?

CR: True Detective, Godless, Patrick Melrose…they are difficult. Patrick Melrose is such an unbelievable experience. You’ve got to watch that. It’s shot beautifully, the acting is impeccable and it’s very fucking hard to watch! It’s tough, and it never pulls back… Godless is a kind of western with women which hasn’t really been seen before—it’s the worst genre for having women in it… And what’s great about True Detective, the first series that everyone loved—and then the second series, which people didn’t love but that I loved even more… it’s a totally different story, but the tone is the same. It doesn’t matter if the main characters are different, and that there’s no narrative continuity. It has the same feel to it. And that’s important, maybe even unique.

My expectations of television are high. When I was a kid I had a very important relationship with that box in the corner. It helped me to learn, to think and to consider aesthetics. That probably why I glommed onto The Prisoner. McGoohan knows, viscerally, that you could use the medium of television to say and show important things.

PB: Twin Peaks was my waking up show. I didn’t like it, to begin with. I thought it was something my parents should watch as I did a half hour and wasn’t interested. Then I re-watched it later that week and got about 40 minutes in, to the scene with Cooper holding the picnic video in freeze frame and stating “the person we are looking for is a biker”—I was completely sucked in at that point.

CR: Yes! That scene, with Bobby, is very important. It’s fairly light-hearted, etc. And then Cooper says to him “You never really loved her anyway.” It’s like a really inappropriately harsh judgement but it’s very important in establishing the constant shifts in mood and tone throughout the rest of the series.

I’ve always remembered that moment. It’s these little touches that help make Twin Peaks something special. Those moments are why I ended up making documentary films, to try to understand how and why they work, and why they seem so true.

PB: So is that what it was with Lynch and his films?

CR: You could tell there were so many interesting things happening. I can’t remember what triggered it all. I think it was because I did some reading about him, seeing some of his art. In those days you had to fax people! I think the main reasons he agreed to do the book was that I wanted to cover his art, his photography, painting etc and not just his film work. And then after the fax I got to call him at a certain time. I didn’t say too much but I remember him saying “IT’LL BE A BLAST!” And it was a done deal on the phone.

PB: It must have been a blast for both of you as he agreed to speak to you again for the revised edition.

CR: It was for me! I don’t know about him (laughs). I blew my paltry advance on just hanging out with David—who wouldn’t? I never wanted to leave, it was such fun. We drank tons of coffee and smoked ourselves crazy! He knew the one place, some burger joint on Melrose, where we could actually smoke inside still. In a dark area at the back of the dining area with banquet seating. And then I had to spend a year and a half editing the book with no money as I had blown it all!

CR: It was for me! I don’t know about him (laughs). I blew my paltry advance on just hanging out with David—who wouldn’t? I never wanted to leave, it was such fun. We drank tons of coffee and smoked ourselves crazy! He knew the one place, some burger joint on Melrose, where we could actually smoke inside still. In a dark area at the back of the dining area with banquet seating. And then I had to spend a year and a half editing the book with no money as I had blown it all!

I did want to do another update but the money isn’t there. There’s so much work that he has done since, a mountain of work to talk about—and it would be a good excuse for me to go over and hang out with him again. (laughs)

PB: What sorts of things would you ask him now?

CR: Loads of things, probably to do with the fact that both of us are 10 years closer to the grave (laughs). It would probably be a lot gloomier! Between the first and second edition, I had a heart attack, so we were always talking about that kind of stuff. And with Twin Peaks: The Return there is that kind of feeling bubbling under the surface, that feeling of yourself changing—your state of being changing, like what might happen when you die. It’s much more evident to me that he’s thinking about these things.

He did say in the early ’80s in a catalogue, he was talking about the comedian (George) Burns dying—that he was like a really ripe peach.

PB: I recall that quote. About the pip?

CR: Yes, that when George Burns dies he is so old, so ripe that when the stone comes out it will come out easily. It was so evocative, so I think it’s something that [Lynch] has thought a lot about that.

There are always TONS of questions that you want to ask people but never do—and probably never will. Plus, new ones keep popping up. Some questions you could only ask if you were very drunk and/or stoned. Some you could only ask if [both the two of you were] very drunk and/or stoned. Some you don’t ask because you’re frightened of what you know the answer is, or might be. Some are absolutely none of your business. And some questions you don’t have to ask because you can hide them inside other questions and/or get an answer anyway.

I have one simple rule. Don’t ask anyone anything that you wouldn’t be prepared to answer honestly yourself. All interactions should ideally be a two-way street, Don’t expect to get something for nothing. Always be willing to give of yourself in return.

PB: I kind of assumed Room to Dream was going to be a Chris Rodley ‘production’. Without touching on anything sensitive for you (if it is), how did you feel about the biography? With so much backstory between the two of you, it seems like you would have felt as comfortable with Lynch’s personal life as much as his artistic one?

CR: I don’t mind touching on the sensitive here. I haven’t read the book because I can’t bear to. And I can’t bear to for one very simple reason: Jealousy. I would have KILLED to do that book. I don’t know why I didn’t, and don’t know why Kristine McKenna did. If I did read it and it was good, that would be crushing. If I did read it and it was bad, I’d just think to myself: “Why didn’t YOU do that book. You could have done a much better job.” So either way, it’s not a good outcome. I WAS tempted to read some reviews and—horrible as it is to admit it—the unfavourable reviews made me feel better. Horrid, I know. Some of the ones I read seemed to find those parts of the book that were not penned by David slightly annoying. The review I liked the best was one that said something like: “don’t bother with this book. Just read Lynch on Lynch”. Like I say, horrid.

I haven’t seen the recent documentary made about David called The Art Life either, for the exact same reason. I’m not going to. I’m just a jealous guy. It’s hard not to feel possessive of your heroes, or those you hold dear. I don’t even like to think of my regular film crew working with other directors!

PB: One of the things that Lynch has opened up more about in the intervening years is his view on meditation.

CR: When we did the book, I sent a copy of it to Lynch and he called me up. I asked him what he thought of it, and he said “CHRIS! I THINK WE SHOULD CALL THIS HORSESHIT ON HORSESHIT!” (laughs) which wasn’t great! So he cut about 14 pages I think, and if I remember they were about meditation and eastern philosophy. Which of course is what he talks about now. In the last 20 years, he’s come out. Maybe he thought [back then] it took away from his art, that if he had bought into a philosophy that it took away from his own imagination.

He’s so articulate about it now, about the unified field and all of that, it all works for him.

PB: Transcendental Meditation went through a period of being considered cult-ish. Perhaps once it became more legitimate and open, and people saw it as simply a meditation? Then there are the studies and proof of it’s working on reducing stress in the brain.

CR: Yeah. It’s possible that David had things going on [back then] where he needed some kind of help, and this was it. I have been tempted myself nowadays, maybe I should talk to him.

PB: I think if you knocked on his door he would say “COME ON IN!” I think a lot of people he works with now have learned. I learned a few years ago and I think it did help me when I had a very dark time. It’s not a miracle thing but I feel grateful for it. I wish I did it more regularly nowadays, I think it would really benefit me again. It’s a time thing—20 minutes twice a day.

CR: It’s interesting as people think something horrible must’ve have happened to [Lynch] in his childhood, he must’ve been abused by his father or taken lots of drugs, all these things that never happened—in order to produce works of that kind of power, with that kind of empathy and understanding, with horrid things in them. People can’t believe he can’t have had a horrid life. It’s nonsense of course.

PB: Do you think that you were trying to get to the bottom of that when you spoke to him?

CR: Yeah. Apparently, there were lots of teenage girls who were abused by their fathers who wrote to him saying “how could you possibly know what that is like?” [after Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me] Meaning how could you know that the only way we could deal with it was to create another kind of character who wasn’t our father, y’know, they’d had to create their own version of BOB in order to cope? I think he is amazingly empathetic.

If it’s true that Lost Highway was kind of triggered by the OJ Simpson trial and OJ getting off for the murders, and then Lynch thinking what must it be like, to have done something so bad that you somehow convince yourself [that] you haven’t done it—that’s a good approach actually. You can either make a brilliant documentary series about it or you can do Lost Highway. That kind of approach, that narrative is going to infect your fantasy life—you’re not going to get away with it.

PB: As an artist and viewer of TV, was Twin Peaks season 3 the right thing to do?

CR: Lynch will always wrong foot you. If you’ve created a big bang, and you have altered the landscape of television forever, how do you create another big bang? I think everyone underestimated him. I think everyone was expecting more of the same.

I mean, I could play the original Badalamenti score on a loop, so I was hoping for more of that ‘cuz I’m an idiot like everybody else! But that wasn’t to be the case. We knew there were something like 217 parts so we knew that most of those people that we loved were going to be reduced to smaller roles. I think it was the right way. I don’t think he’s arrogant enough to realise that he had created the television landscape that most of us live in now, I think he just wanted to do what he wanted to do.

You have to protect and get on with your idea. We had to wait till almost the penultimate episode to have Special Agent Dale back. After like 16 hours…

I am frightened to watch the whole thing again. I have the Blu-ray but I have some fear of watching it again, I don’t know why that is—either I will never come back from it and just keep watching it forever or I will find it frustrating in some way, or won’t like it in some way.

PB: I get that. I had a feeling similar to that. It took me time to re-watch on the Blu-ray but I think I enjoyed it more as I relaxed a bit more. There were such expectations the first time I watched it.

CR: Back in the early ’90s we had Twin Peaks parties, we took it very seriously. We didn’t have True Detective parties!

PB: Nowadays people use Facebook or Twitter to talk about it, even whilst the episode is actually on.

CR: Oh no, no. I don’t do that. That’s a no.

PB: What was/were the most surprising of results from your time with Lynch? (1993 through to 2002) and beyond?

CR: First and foremost, there was no way I could have either predicted or imagined the extent to which David has become an influence in my life. Weirdly (or appropriately) I often dream about him. I also think about him often when I’m awake. I sometimes find myself taking up aesthetic positions that he might take. I even enjoy doing a pretty bad impersonation of him! I have no way of explaining any of this, and while it might sound a bit fan-ish or obsessive (it really isn’t, by the way) the very little time we’ve actually spent together over the last 20 years—first working on the book together, then updating iT—are times that I treasure.

This is far from unique, by the way. You might be forgiven for finding yourself suffering from Gushing Admiration Syndrome (GAS) when exposed to the many besotted comments from people who have worked with David. Someone (it might have been the singer Chrysta Bell) even claimed that he was possibly the most creative person who EVER existed!

Embarrassing as that statement is, I understand something of what she means and why she may have said it. You only have to look at the sheer breadth of David’s work—film-making, photography, painting—ALWAYS painting—music, illustration, writing, acting, furniture making (you name it, he does it), to realise that he is pure creativity on two legs. And that’s super attractive.

I don’t think that artists are ahead of their time. I think that they’re IN their time, and that it’s the rest of us who are lagging behind. Similarly, I don’t think that David is “Jimmy Stewart from Mars” or a man from “another place”. He’s one of us, but someone who is close to realising his full potential. It’s the rest of us are just pissing most of ours away which—according to William Blake—is truly, truly a sin.

PB: Having covered so many diverse artists, etc. so far in your career, who would you most like to meet and cover for a documentary in the future?

CR: The older I get, the more I find that the people I really want to interview are those who have affected my personal and artistic life the most; those who have given me the most to marvel at, struggle with and aspire to. Over the years I’ve been lucky enough to spend some time with a quite few of them anyway. The trouble is that many of those artists I didn’t get to interview but would still LOVE to—and maybe even could have, given the right circumstances—are now dead. In fact, many of those I have interviewed—and in some cases have become friendly with—are also now dead. That’s even worse.

One of the great things about what I (mostly) do is that I’m constantly surprised by conversations or filmed interviews with artists: by what they say, and how they say it. You might think that the next interview you’re about to do isn’t going to be very interesting and BANG!—suddenly you’re talking about the meaning of life together. Everything goes very quiet. Something happens. And afterwards, the film crew packs everything away in silence.

Unfortunately, sometimes it’s the other way round, and heroes turn out to be dull when you sit down with them. Go figure.

If you enjoyed this interview, please be sure to check out some of our others!

Rebekah Del Rio discusses meeting David Lynch, Mulholland Drive, No Stars and more!

Bob Engels Talks About Judy, Fire Walk With Me, 1954, Seasons 1 & 2 & More!