I recently had the opportunity to speak with John Thorne from Wrapped in Plastic Magazine and The Blue Rose Magazine, as part of my “Twin Peaks Topics” series. In this series, I ask my guest to choose any one topic related to Twin Peaks and we will have a discussion based around that topic. John selected the topic of compassion in Twin Peaks, which lead to a lively discussion, with a few slight detours into larger, more theory-based discussions. Be sure to check out previous editions of Topics, with JB Minton and The Bickering Peaks!

AG: I wanted to start by asking what compelled you to pick compassion as your topic?

JT: I’ve been writing on The Return for coming up on a year now, and there are a lot of themes and issues in the 18 hours that may have been somewhat overlooked or that didn’t stand out as much on first viewing. Compassion seemed to me to be a fundamental aspect of the series that is worth discussing. There’s some criticism of The Return that it was kind of cold, kind of remote and that it didn’t have the same endearing qualities that the original series did. There’s some legitimacy to that criticism and it’s worth looking at why there’s some distance between the viewer and what’s happening on the screen, as opposed to the original. I do believe that there’s a very strong emotional component to the show and that has to do with this idea of compassion and this idea of how we treat our fellow human beings. It’s very meaningful to me as I watch. I see it in a lot of different places and it felt worth discussing. I haven’t seen it discussed in a lot of different places. I have seen it discussed other places a little bit and maybe its been discussed at length and I just don’t know about it but I haven’t seen it and it felt like a good topic that was worth exploring.

AG: Let’s use the character of Dougie as our entry point into this discussion.

JT: Dougie’s a fascinating character. The more I watch this show, the more I like the character. When I say like, I mean I value the Dougie character. I find great worth in that aspect of the story, which has been criticized a great deal as being slow, meaningless and well, you’ve seen the things said. I think people may be missing the bigger point of Dougie. I’ve written a whole essay on this. Dougie is a being of literally pure goodness. I would argue that he is essentially an angelic presence and we know that angels have been a part of the narrative, at least in Fire Walk With Me. I would argue that Doug is this presence that no matter whom he comes in contact with, they become a better person. He makes the Mitchum brothers better people. He makes Bushnell Mullins and Anthony Sinclair better people. He certainly makes Janey-E a better person. Compassion isn’t the first term I would use towards Dougie but people become compassionate towards him when they are exposed to him. In a general sense, people become better people because of Dougie. That can mean a lot of different things but one of those ways is to start showing compassion toward your fellow man.

One of the people Dougie changes is the Slot Machines lady. He doesn’t just make her rich; he changes her life. When she encounters him again in the restaurant, she thanks him profusely and says that he saved her. She’s now reunited with her son and she turns to the Mitchums and says that she hopes they understand just how important this person is. Its this sense of looking out beyond your self with the characters that Dougie encounters. My basic takeaway from Dougie is that he does instill that in other people and makes them care for each other and the world they live in, as well as regret for bad choices they’ve made. I find that fascinating. I think it’s an important element of the whole story.

AG: Shortly after The Return, I wrote an essay where I claimed that The Return was the story of changes in America and society from the perspective of men Lynch and Frost’s age. The coldness we spoke of earlier seemed to be particularly present in the younger generations in the show. It felt like we saw the older generation acting more on core values that aren’t as prevalent in society today and that in a sense, plays off the duality that we see all throughout Twin Peaks.

JT: That’s interesting that you say that. Obviously Lynch and Frost have matured and have lived a lot of life and that has impacted the way that they looked at this new story. The idea of mortality and of memory and the latter part of your life is an essential element to the story. Some of the way that you see that is the fact that Cooper has missed 25 years of his life. When Cooper returns and he only returns for a very short amount of time, he is almost unaware. I think Dougie is aware of what he’s missed. He sheds the tear when he sees Sonny Jim in the car and Cooper deep down inside recognizes that he’s missed a great deal of life. I think you’re definitely onto something and that Lynch and Frost were deliberate in looking at how you look back at your life, what’s important in your life and what is important to us in our lives. Those things are there and are deeply woven into that tapestry.

AG: My interpretation of the final scene in Part 18, when Cooper says “What year is this” has always been that it’s his realization that he’s lost so many years of his life. I’ve always viewed that as a heartbreaking revelation that he’s not the same age as when we last saw him at the end of Season 2.

JT: That’s very true and in the supplementary materials that were released in the boxset, there’s a sequence where Cooper is running into the Sherriff’s station from Part 17 and Kyle turns to Lynch and asks him how to react to seeing Andy. Lynch tells him that no time has passed for him, which I think is one of the most critical pieces of direction for us as viewers to know. For Cooper, when he comes back, no time has passed. He doesn’t see that people have changed. This is getting away from compassion but my way of watching most of the show is that we’re seeing it as Cooper sees it. We’re watching these events as he sees them. Part of why the characters are so static and unchanged and so many haven’t progressed because we’re seeing them as Cooper sees them and no time has passed for them. Even though obviously they are older and have had some life, what we’re seeing is still filtered through Cooper. I think that’s supported by how Lynch directed Kyle, no time has passed. In those moments, he doesn’t recognize that time has passed for them and perhaps in the end, as you say, it dawns on him that he’s missed a lot. There is a tragedy there.

AG: Let’s dive into some other examples of compassion that stand out to you.

JT: There’s a lot. Let’s go back to a particular Log Lady introduction, outside of The Return, where she discusses how we treat the people around us. It was a theme that was important to Lynch back then and it stayed with him and he wanted to look at it in The Return. He’s certainly done it in his films, in particular, The Straight Story, which is a lot about how we treat other people. We start to see it manifest in The Return quite a bit. One of the most striking examples to me was Frank Truman and his wife Doris. When we first met her, she seems crazy and he just tolerates her. It falls into the stereotype where you have a wife who is kind of a nag. We had that stereotype back in the original series with Nadine and Big Ed. Then there’s this layer of depth that’s added when we find out that they had a son who had killed himself. We can assume he had PTSD based on things that were said about him being in the military. In those few moments when we find that out, when Maggie the dispatcher is telling Chad what happened, all of a sudden, the door is opened to this deep backstory. Although we won’t see Doris again and we won’t address it again, it’s now there in the room with us. We know what these two people have gone through and it’s likely that Doris Truman has had some sort of breakdown and she’s suffering. Frank Truman is going to stand by her. He is going to be true to her and do his best to support her. There’s a tragedy there and a sense of who he is and how compassionate he is, in just a few lines and a few scenes. Great depth is added to that character and he becomes to be such a valuable character to look at and admire.

Another instance is certainly Carl Rodd, who is the embodiment of compassion in the story. The most obvious example is him being helpless when the mother is suffering in the intersection after her child has been run over. Everyone else is standing there in anguish and Carl kneels down there with her. You’ve got this strong emotional connection where he shows compassion and is just there for her. Later in the narrative, when a resident at the Fat Trout Trailer Park, Criscol, walks by and Carl realizes that he’s been selling his blood to pay his rent. Carl tells him he’s not going to do that anymore, that he can come to him and mow the lawn and not to do these things anymore. He’s showing compassion for this man and he wants to help him.

AG: I’m thinking about Nadine and Ed as well.

JT: Oh yeah. Ed has chosen, like Frank Truman, to stay with this woman and to care for her, to comfort her and to be compassionate towards her because she is suffering. She frees herself through the words of Dr. Amp and when she frees herself, she frees him. When she frees him, he can go to Norma. It’s a chain reaction. There’s a fascinating scene that happens there when Ed and Norma get back together. We see Shelly standing aside, watching it happen. This was Shelly’s last scene in the season. The implication, at least for me, was that this compassion and this caring is passed from person to person. It passed from Nadine to Ed, then from Ed to Norma and then Norma to Shelly. There’s a hope that maybe Shelly can rid herself of someone like Red and make her life better. Big Ed is a great example of someone who didn’t discard someone who was hurting. It’s very moving, very powerful.

AG: The direct contrast with some of the more heavy material, the darker material that sometimes gets more credit or attention than the more compassion-based material, really makes the story what it is.

JT: It’s true. We talked earlier about Dougie being this being that makes everyone around him better, but by contrast, Mr. C is a being of negativity that corrupts anyone he comes into contact with essentially. We don’t know the history of Hutch and Chantal but they will do anything for him, without question. Even the gang that has the arm-wrestling contest, once he defeats Renzo, they’ll all now do anything for Mr. C. Even the accountant offering money. Yes, there’s a code of beating the boss to become the new boss but it was more than that. Its that corrupting influence that’s radiating off Mr. C. He’s the exact opposite of this pure Cooper where the goodness is radiating off him. The contrast is fascinating.

AG: To go back to Frank and Doris Truman for a moment, we see that exact contrast in the same scene with Chad doing the fake cry. We don’t always see the contrast in the same scene but that always stuck out to me as being fascinating.

JT: It is. Of course, by Chad mocking them, we feel even more for them. He trivializes their pain but its not trivial. It’s very real.

AG: Throughout all of The Return, there’s this snapshot mentality where we get a brief moment in time with many characters. Little context, just the here and now, in the moment with these people. There’s a lot of examples of us getting 30 seconds to a minute with certain characters and then we’re left to fill in the blanks on what else is going on with them.

JT: A great example of that is Beverly Paige. She leaves work late and goes home and we find out that her husband is dying of cancer. It’s not explicit but you can assume that’s what it is. She says to him that she knows he is suffering. Now she is struggling because it’s hard on her. It’s hard on both of them, the stress of this illness in their lives. They may not seem like it but they’re trying to be compassionate. She says she didn’t want to go back to work but she did. She’s sacrificing but she’s also complaining some. You don’t see that from Frank or Ed but we shouldn’t criticize her. It’s hard. She’s in an emotional state and she’s responding to his somewhat stubbornness. It’s a natural tension and conflict. You can tell she wants to take care of him and he, in all likelihood, is afraid of losing her. There’s this deeper emotional connection there. As you said, it’s all of a minute and a half. It’s done and we never come back to that story again. Its an important part of the overall theme in the show of caring for someone else, showing compassion.

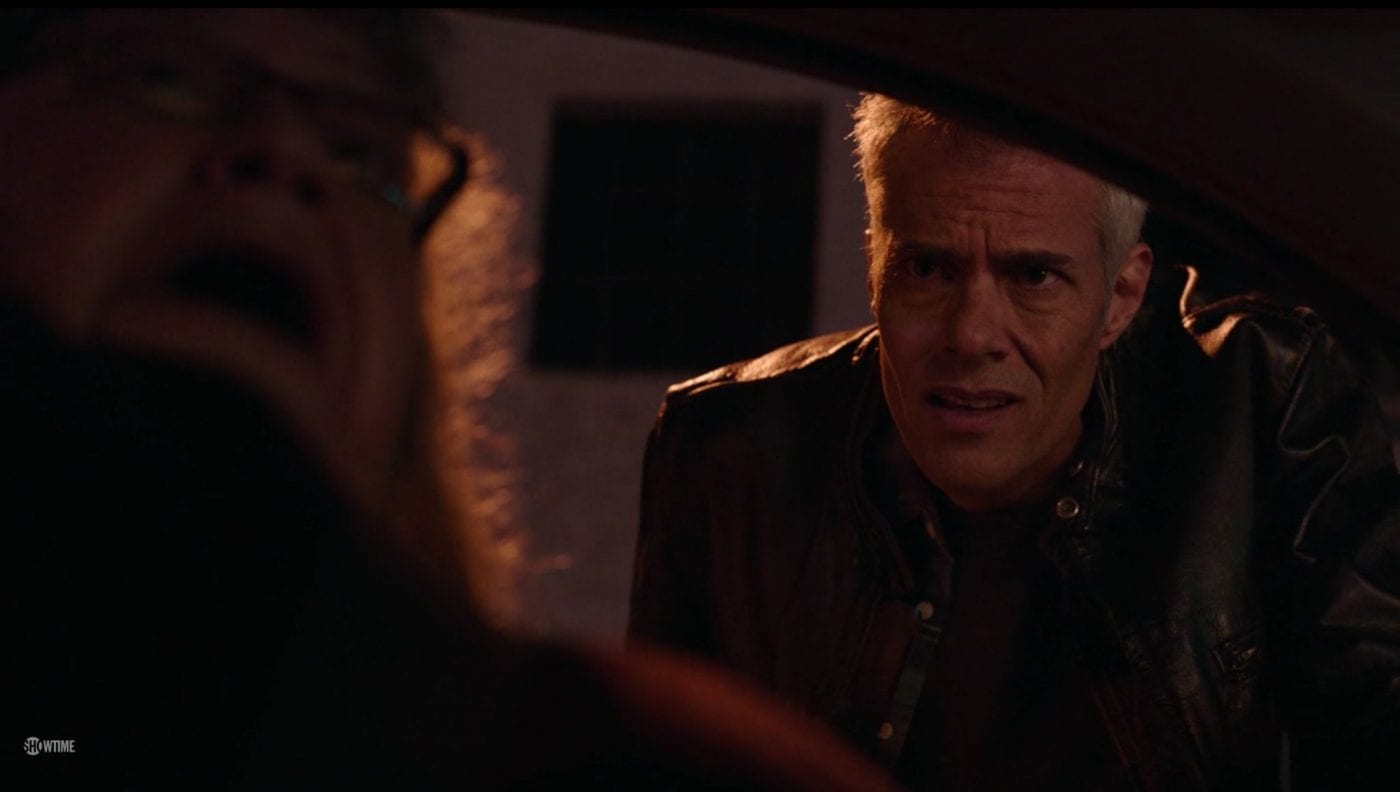

AG: I felt like we had a few of those moments with Bobby where we started to touch upon something and then we’re left to fill in the blanks. The photo of Laura was a great example. What was he thinking there? We’ll never know. There are different ways it can be interpreted. Then in Part 11, Bobby and the lady in the car is another great example.

JT: There’s sort of a metaphorical aspect going on there, as he had just been dealing with his daughter, who he probably knows has been involved with drugs and a violent encounter, which involved gunfire. It’s almost as if these deep emotional aspects of his life manifest themselves and become reality. Suddenly there’s gunfire and he runs outside the Double R. He sees this woman in distress and this passenger rises out the dark, vomiting and I read it as this is all a reflection of the turmoil inside Bobby. This teenage girl is suffering and I see that as a manifest of Bobby’s fear over what might happen to Becky with drugs and suffering. Of course, there’s the gunfire which I see as a parallel to what Becky did, which speaks to the mental landscape of Bobby Briggs in that moment. That’s how I read it and I find that whole thing fascinating. Just like with Beverly and countless other instances, it is never addressed again. You would think that maybe the characters might reference something like this in a later episode but they don’t. Just like with Andy and the scared farmer. These scenes open a story and then never go anywhere with it. I think it’s sort of a new kind of narrative in a way. It’s not your traditional story where you throw a subplot in and then address it later. You threw a subplot in because it is speaking to the theme. The theme here is that people are suffering. We don’t need closure, we just need to know that it’s happening. For some people, I think it really is hard to accept that. I think those deeper meanings become more apparent with multiple viewings and you come to appreciate this kind of storytelling than you would get in a traditional narrative. It’s far more challenging but if you give yourself to it, you get a lot from it.

AG: One example that really stuck out to me of compassion missing was Ruby in the Roadhouse at the end of Part 15. The image of this woman, crying out, yet being completely ignored was something I always found very striking.

JT: That’s the episode where we find out The Log Lady has died and also where Dougie sticks a fork in the outlet and Janey-E screams, foreshadowing Ruby’s scream. For me, Ruby’s scream was a release for everything that lead up to it. What else can you do, you have to scream. It reminded me of the original series when Josie’s face appeared in the knob. There’s this anguish and there’s no other way to express it.

AG: Lastly, we can’t discuss Twin Peaks without discussing Laura Palmer. When Senorita Dido releases the “Laura Orb” in Part 8, that to me felt like an act of compassion. Wanted to get your thoughts on that.

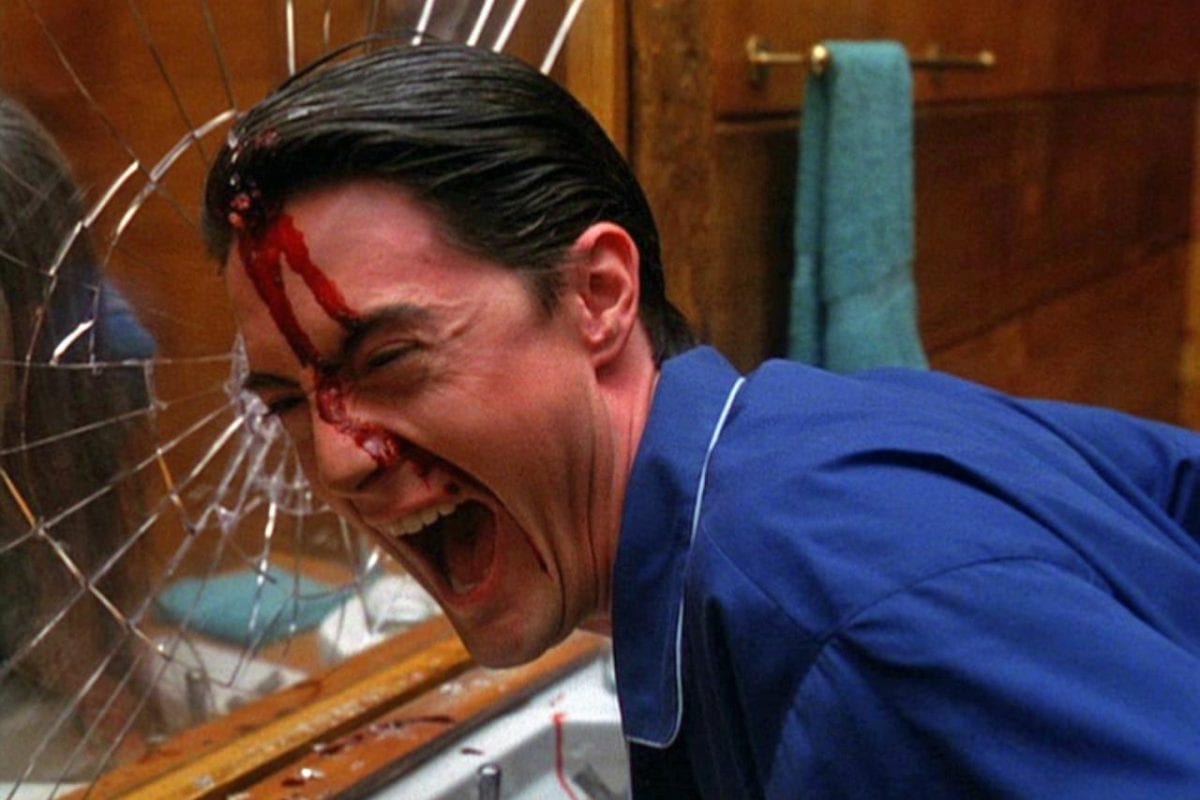

JT: My theory is yes, Laura is being sent to Earth to counter the evil that is BOB. The Fireman and Senorita Dido in a sense are her true parents but she has a mission to fulfill. There’s an element of compassion there but there’s something more profound at play. One of the fascinating things about Fire Walk With Me is that we see BOB try to break Laura down so he can ultimately possess her as his vessel. One of the ways they try to make her susceptible to BOB is—I say them because I think BOB is working with The Arm, is to get her to harm someone. I think you see this in Lynch’s films, that when you hurt someone else, you open yourself to a very dangerous world. You see it in Eraserhead, in Blue Velvet when Jeffrey hits Dorothy. It’s right after that, that Frank Booth says to Jeffrey that you’re just like me. Its really pronounced in Mulholland Drive when the hitman tells Diane that if she does this, there’s no going back. Laura Palmer in Fire Walk With Me faces a number of examples where she can either harm someone or allow someone to come to harm. One of the best examples is Donna in The Pink Room. She knows that Donna has been drugged. Laura is to some extinct responsible for putting Donna in harm’s way. She realizes it at the last moment and saves Donna. Laura never hurts anyone. She hurts herself. She’s not necessarily being compassionate but she’s refusing to harm anyone. That I think, is how she ultimately recognizes at the end that she is in fact, good.

In which episode and series did Ben Horne mention to his daughter Audre that five great books of wisdom have been written: (1) The Holy Bible, (2) The Koran, (3) The Bhagavad Gita, (4) Tao (Lao Tzu’s The Way) and (5) The Talmud?