The following is a guest post from Dr. Reba Wissner! Her bio is included after the sources at the end of the article. For more discussion on music in Twin Peaks, please check out Listen to the Sounds: The Featured Music of The Return So Far , Listen to the Sounds: The Music of the Return Parts 9-15 and Listen to the Sounds: The Featured Music of Twin Peaks Parts 16-18 and 1-8 Revisted. Hope you enjoy!

I’m sitting in my living room, watching Part 16 of The Return. I had already screamed at the TV once that hour when Agent Cooper told Bushnell Mullins that he IS the F.B.I. The episode is coming to a close and Audrey is in The Roadhouse with Charlie. The announcer introduced “Audrey’s Dance” and, stunned, she looks at Charlie before approaching the dance floor and doing her “isn’t it too dreamy dance” from the Double R. There were moments before this, sure, that pulled on my nostalgic heartstrings, like when, the playing of “Laura Palmer’s Theme” in Part 4 when Bobby sees Laura’s famous homecoming portrait on the table as Hawk, Lucy, and Sheriff Truman try to figure out what’s missing from the case files, during James’s performance of “Just You” in The Roadhouse during Part 13 that was introduced by the announcer and used the same audio from season 2, the blaring of the Twin Peaks theme when Agent Cooper “wakes up” from his Dougie state in the hospital earlier in Part 16, or Julee Cruise’s return to The Roadhouse in Part 17 with a reprise of “The World Spins.” But nothing got to me quite like “Audrey’s Dance” and it pulled at my nostalgic heartstrings. At that moment, the only thing I could mutter was, “Oh my God.” Some people have recently contended that The Return is anti-nostalgic or defied nostalgia, but I believe that the music renders this incorrect. So, what is it about the way that Angelo Badalamenti’s music from the first two seasons is used in The Return, especially in Part 16, that makes us nostalgic?

There is an interesting way that music is used in Twin Peaks on the whole. In the first two seasons, Lynch does what I call playing with the diegesis. In film music, music that is diegetic, or part of the diegesis, is music that both the audience and the characters can hear, like the music that the jukebox plays in the Double R or the music we hear on the radio when Shelly and Bobby are sitting in the car. Non-diegetic music, or music that is not part of the diegesis, is music that only the viewer can hear. Music that is often diegetic, like “Audrey’s Dance,” is sometimes brought into the diegesis such that we initially think it is background music until we see that the character can hear it too, like the famous Double R scene where Audrey turns on the jukebox and her dance begins to play, or when Bobby turns off the car radio and we now see that the music that was originally non-diegetic can be heard too. In The Return, this is especially acute in “Audrey’s Dance.” Not only do we get to relive the moment that she first danced to it in the Double R, but she does also. It directly plays on her nostalgia, right down to the moment when her father tells her in season 1 that she’s disturbing the guests with this racket,” this racket being “Audrey’s Dance.”

We know that music, especially in film and television, can evoke nostalgia for the viewer. We also know that Lynch specifically intertwines his music with visuals. There is a scientific basis, however, in why we find music nostalgic. There have been studies done about why we are nostalgic for music from our teenage years. It has to do with the way that our brains are wired because it is during these years that we make neural connections to specific music, especially that which we like and that often, music is heavily intertwined with our social lives. One study found that music that is significant in our lives tends to evoke nostalgia more than those pieces that are not. For many of us, we were teenagers during Twin Peaks’ original run and we heard Badalamenti’s music over and over each week, so its rendering of nostalgia should come as no surprise given these points.

Aside from the show’s theme, which has thankfully remained untouched aside for some small, barely noticeable changes, the music—and its use—in The Return is strikingly different from that of the first two seasons. The music that is associated with certain characters like “Laura Palmer’s Theme” and “Audrey’s Dance” permeate the first two seasons like musical wallpaper in that their presence is pervasive. Even when they shift associations—and shift from the non-diegetic to the diegetic, they are imprinted in our minds because of their frequent use. In The Return, not only is the use of music sparser it is also unlike Badalamenti’s jazz- and pop-influenced pieces from the first two seasons. Therefore, when these original pieces come back in The Return, they immediately offset the scene in which they appear from the scenes before or after it. Music from the first two seasons are reused in various situations within the same context in The Return or is evocative of characters or events from the first two seasons. In her New York Times Magazine article on The Return, Alexandra Kleeman notes that “When favorite characters from the original seasons reconnect, their interactions seem interminable, the exchange of glances is drawn out past all reasonable limits.” And, indeed for us, the use of the original music not only connects the characters with each other but with us. Immediately, while watching Audrey dance, I couldn’t help but think back fondly on the Double R scene in season 1. Part of what makes Twin Peaks what it is is the music. Even Lynch acknowledged this association of the show with Badalamenti’s scoring from the first two seasons, noting that “So much of what Twin Peaks is in people’s minds is Angelo’s music.” It is not inconceivable then that for fans of the show, hearing the music out of context, for example, Moby’s sampling of “Laura Palmer’s Theme” in “Go” evokes a memory of the show.

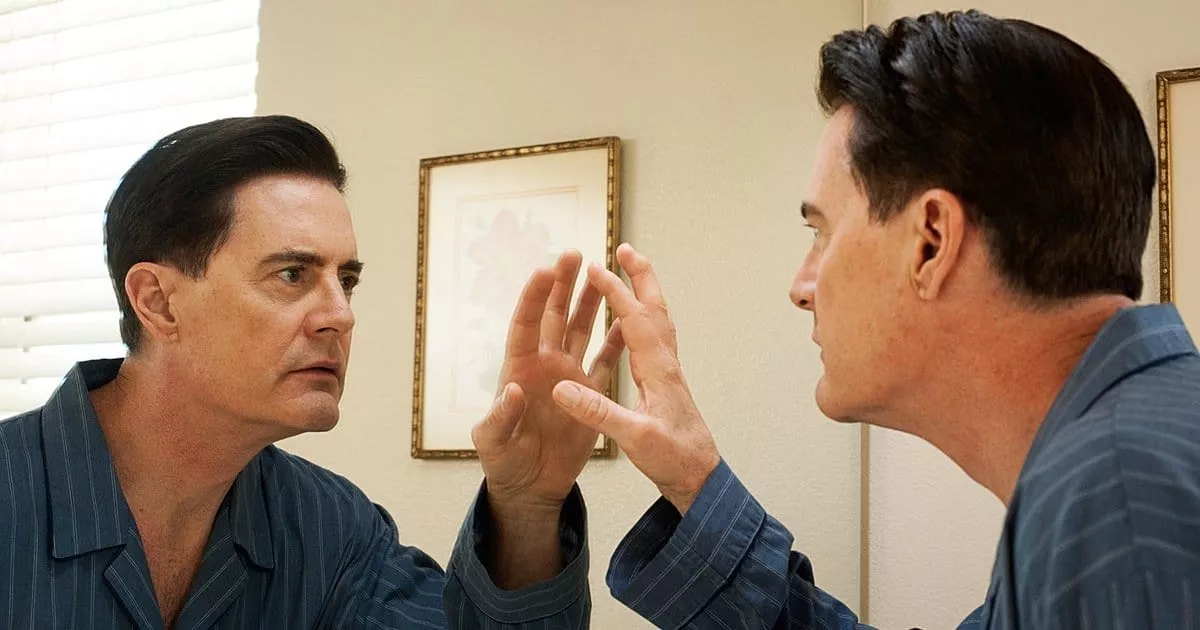

Twin Peaks, on the whole, is a study of nostalgia itself, hearkening back to the fifties in the context of the late eighties. The music that plays on the jukebox in the Double R, for example, tends to be reminiscent of mid-century jazz and pop. In The Return, this hearkening back is continued when we hear the strains of Otis Redding as Norma and Big Ed finally—finally!—have their happy moment. Certain visual moments have this effect, too, like when Cooper-as-Dougie looks in the mirror in the Jones house in his pajamas, a stark reminder of the final scene of the second season. But it is the music that has the power to amplify these important moments and bring us back to the Twin Peaks that we love. The presence of music that reminds us of our past, either in style or by its sheer presence, can affect us emotionally and this is precisely what occurs when music from the first two seasons return.

Often, the use of Badalamenti’s music from the first two seasons in The Return are self-referential, as in “Audrey’s Dance” in The Roadhouse or James’s rendition of “Just You” in which not only the same recording from the second season is used and his brunette backup singers here remind us of Donna and Maddy. We can immediately picture—for better or for worse—that living room scene as we are relocated to another mainstay of the series on the whole, The Roadhouse. These self-referential scenes in music are the most nostalgic of the series because they not only remind us of the first two seasons but also they connect The Return to the first two seasons in a way that most of the plot devices could not. They draw us back into the narrative world that we left behind over 25 years ago through sound rather than images.

We may never know what happened to Audrey (though my guess, given that her dance was played backwards during the end credits of Part 16, that it may have to do with the Black Lodge) or if Carrie Page remembered that she really is Laura Palmer, but use of the music from the first two seasons in The Return provides more information about what’s really going on that we might think. Like Audrey, whose dance is rudely interrupted by waking up in a white room, horrified, so too are we snapped out of our nostalgic enjoyment at the end of the scene, reminding us that there is, after all, darkness in future’s past.

Sources:

Barrett, Frederick S., Kevin J. Grimm, Richard W. Robins, et al. “Music-Evoked Nostalgia: Affect, Memory, and Personality.” Emotion 10, no. 3 (2010): 390-403.

Chaney, Jen. “Twin Peaks: The Return Defied Nostalgia.” Vulture, September 4, 2017. http://www.vulture.com/2017/09/twin-peaks-the-return-finale-nostalgia.html

Ebiri, Bilge. “David Lynch’s Irresistible (and Corrupted) Vision of the American Past.” LA Weekly, May 20, 2017. http://www.laweekly.com/film/david-lynchs-irresistible-and- corrupted-visions-of-the-american-past-8238922

Herman, Alison. “Twin Peaks: The Return Pushed Past the Limits of Nostalgia.” The Ringer, September 4, 2017. https://www.theringer.com/tv/2017/9/4/16251638/twin-peaks-the- return-finale-david-lynch

Kleeman, Alexandra. “The Slowness of Twin Peaks.” New York Times Magazine, October 8, 2017: 38.

Lynskey, Dorian. “‘Make it Sound Like the Wind, Angelo’: How the Twin Peaks Soundtrack Came to Haunt Music for Nearly 30 Years.” The Guardian, March 24, 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/music/2017/mar/24/twin-peaks-soundtrack-david-lynch- angelo-badalamenti

Murray, Noel. “’I Love Winds’: David Lynch on the Sound of Twin Peaks.” New York Times, August 17, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/17/arts/television/david-lynch-twin- peaks-interview.html

Sprengler, Christine. Screening Nostalgia: Popluxe Props and Technicolor Aesthetics in Contemporary American Film. New York and Oxford: Berghan Books, 2009.

Stern, Mark Joseph. “Neural Nostalgia.” Slate, august 12, 2014. http://www.slate.com/articles/health_and_science/science/2014/08/musical_nostalgia_the _psychology_and_neuroscience_for_song_preference_and.html

Dr. Reba Wissner is on the music history faculty at Montclair State University, New York University, Westminster Choir College, and Ramapo College and on the film and media studies faculty at Rider University. She is the author of several books and articles on music in television and is co-editing a volume titled Listen to the Sounds: Music and Sound Design in Twin Peaks.